Mycophenolic acid is generally well tolerated and its most notable adverse effects are gastrointestinal (nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea) and haematological (leucopenia, anaemia and thrombocytopenia). There are two different pharmaceutical forms: as ester, mycophenolate mofetil (MMF); and as sodium salt, mycophenolate sodium (MPS). The sodium formulation, with intestinal and not gastric absorption, was developed to reduce the incidence of gastrointestinal adverse effects.

Although gastrointestinal intolerance is common, published cases of liver involvement are very rare, and almost always associated with MMF. We present what we believe is only the second published case of acute hepatitis associated with MPS.

This was a 68-year-old woman, diagnosed seven years previously (November 2011) with polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) vasculitis with MPO-ANCA serology which presented in the form of pulmonary and renal involvement. She was treated with steroids and oral cyclophosphamide, with almost total recovery of her previous renal function. A year and a half later (May 2013) the patient had a second flare-up, again with pulmonary haemorrhage and renal dysfunction, which once again was treated with steroids and cyclophosphamide bolus, subsequently starting maintenance treatment with azathioprine. After the second flare-up, the deterioration in renal function persisted and continued to progress over the following year until she had to begin peritoneal dialysis (October 2014). She had remained on peritoneal dialysis since then, without any incidents of note for three and a half years. Given the stability of her condition, and the fact that she was already on dialysis, the decision was made to discontinue azathioprine after two years of treatment. Then in June 2018 she developed severe asthenia, arthralgia and an irritative cough, which was causing haemoptysis within a few days.

In the initial investigations, blood tests showed normal blood count, clinical biochemistry consistent with the patient’s renal failure, ANCA of 34, CRP 68 and normal complement. Chest X-ray revealed bilateral and multifocal pseudonodular parenchymal opacities, confirmed on chest CT, highly suggestive of bleeding, which was confirmed by bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage.

As a new flare-up of her vasculitis was suspected, treatment was started with boluses of methylprednisolone and then, after evident clinical and radiological improvement, was continued with oral prednisone (60 mg/day) to which MPS (180 mg/12 h) was added as a supplementary therapy. After two weeks of treatment with MPS, the patient developed peritonitis caused by Enterococcus Faecium. The mycophenolate was discontinued and antibiotic treatment started with intraperitoneal vancomycin, for 15 days, with a favourable response and outcome.

A month after starting treatment for the vasculitis flare-up, the patient’s ANCA values were negative and her CRP had returned to normal. Once the peritonitis had resolved, and having already begun the oral prednisone tapering regimen, it was decided to reintroduce the MPS in smaller doses (180 mg/day).

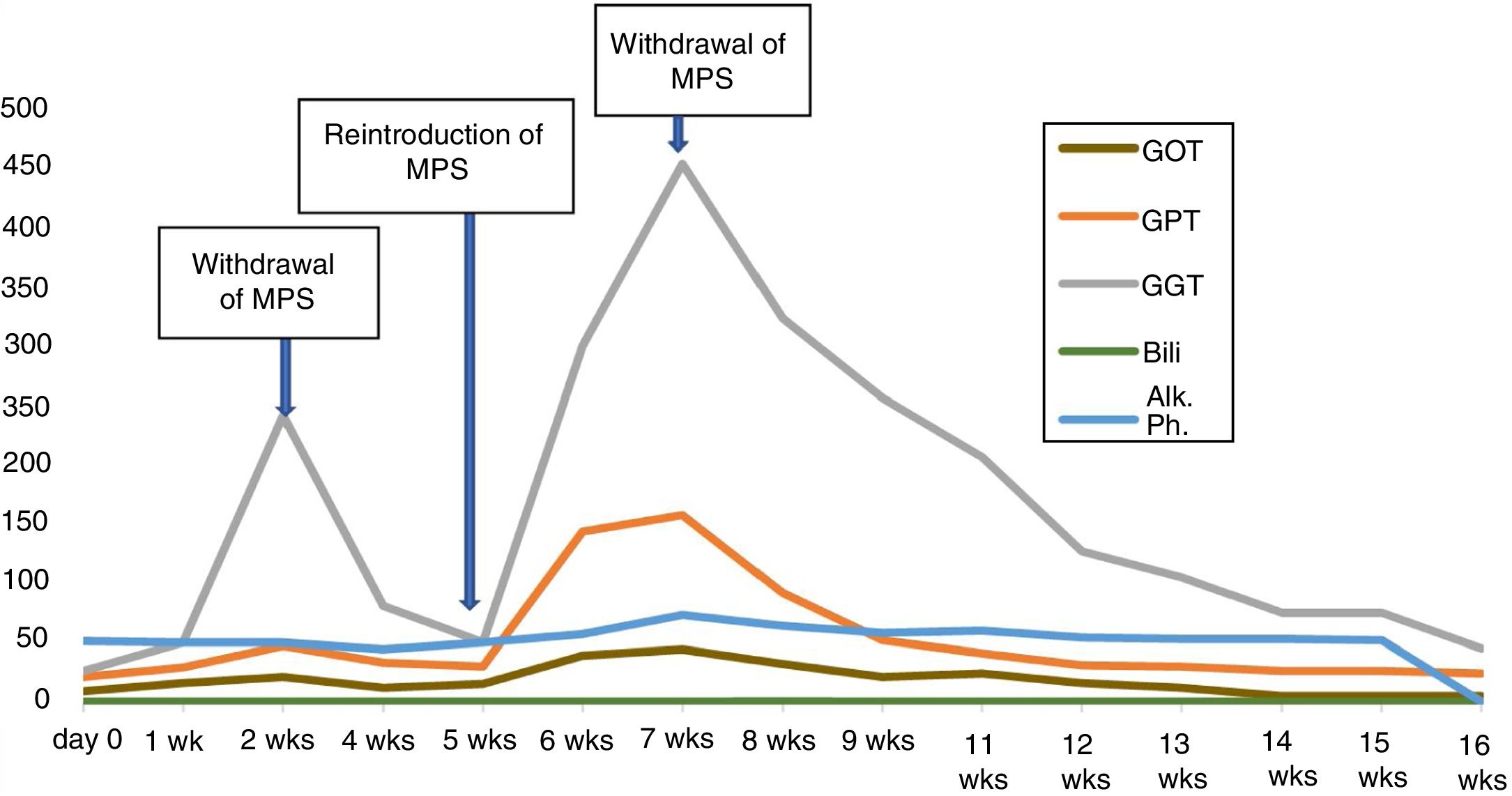

Two weeks after reintroducing the MPS, follow-up bloods showed elevation of transaminases (GOT 44, GPT 158 and GGT 455 IU/l), with normal bilirubin, albumin and coagulation. CRP was also normal. The patient denied having any symptoms and had no signs of jaundice or hepatomegaly. Reviewing previous blood tests results, we found that the elevation of transaminases coincided with the restart of treatment with MPS. We also found that this enzyme abnormality was already present, although to a lesser extent (GOT 21, GPT 85 and GGT 250 IU/l), before the temporary withdrawal of the drug due to the peritonitis (Fig. 1). After that withdrawal, the transaminase levels had returned to normal.

In view of these findings, we decided to withdraw the MPS again, and rule out other causes of liver involvement. The patient had no history of liver or biliary disease, alcohol abuse or drug addiction, had no exposure to liver viruses and had not travelled to any exotic locations. Nor had she started treatment with any new drugs and she denied taking NSAIDs. Virus serology, including atypical liver viruses and CMV was negative, as were the anti-mitochondrial, anti-smooth muscle, anti-KLM, anti-liver cytosol, anti-SLA, anti-nuclear and anti-actin antibodies. ANCA remained negative.

Repeat blood testing two weeks after discontinuing mycophenolate showed a decrease in transaminases, and they had returned to normal levels at 16 weeks.

Despite the large number of patients treated with mycophenolic acid, liver involvement has been described very rarely. The pharmaceutical form involved in almost all of the cases has been MMF.1–4 Transaminase elevation is mild-to-moderate, asymptomatic and usually occurs in the first month of therapy, with a hepatocellular pattern or, more rarely, mixed (hepatocellular and cholestatic). It is not usually accompanied by immunological or autoimmune data and resolves with dose reduction or drug withdrawal. The number of clinically apparent and/or severe cases is minimal.5,6 The liver damage mechanism is not fully understood, but could be the result of toxicity or immunogenic stimulation from any of the metabolites.1

Reviewing the literature, we only found one case of hepatotoxicity associated with mycophenolate sodium,7 although that patient suffered from C-liver disease, which the authors believed might have increased the toxicity of the MPS.

In our case, the causal relationship is supported by the temporal relationship between the administration of MPS and elevation of transaminases on two occasions, the absence of other possible aetiological agents and recovery after withdrawal of the drug.

Please cite this article as: Moreiras-Plaza M, et al. Hepatitis aguda por micofenolato de sodio: ¿el segundo caso? Nefrologia. 2019;39:561–562.