To the Editor,

The relationship between membranous glomerulonephritis (MGN) and cancer is no accidental; this is a classic paraneoplastic phenomenon. Approximately 25% of these cases are secondary (10% neoplastic).1 Here, we describe two clinical cases of membranous glomerulonephritis secondary to lung cancer with different patterns of presentation.

Case 1. Our first patient was a 49-year-old male with hypertension, sleep apnoea-hypopnea, who smoked 40 cigarettes per day. He was admitted due to anasarca, showing nephrotic syndrome (proteinuria: 19g/day), no haematuria, and normal renal function. An immunological analysis was negative for antinuclear antibodies and anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies; C3 and C4 levels were normal. There was no monoclonal spike in serum proteinogram, the virological study (HbsAg, HbcAb, HbsAb, hepatitis C antibodies, and HIV antibodies) was negative, and tumour markers (prostate specific antigen [PSA], carcinoembryonic antigen, and alpha-fetoprotein) were normal.

Chest x-ray revealed pleuropulmonary parenchyma and hili without pathological signs, except for very mild bilateral pleural effusion. Renal biopsy was diagnostic of stage I MGN. Immunofluorescence analysis showed subepithelial granular deposits strongly positive for IgG.

The patient was started on conservative treatment with angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB) and a diuretic drug. After three months, the patient was admitted on two separate occasions due to anasarca and poor response to treatment, and was started on immunosuppression with cyclosporine (CsA). By the fifth month post-biopsy, he showed moderate effort dyspnoea and significant right pleural effusion. We performed a thoracentesis with a positive cytological test for malignancy. A thoraco-abdominal computed axial tomography revealed numerous positive lymph nodes. Bronchoscopy was performed, confirming stage IV lung adenocarcinoma with right pleural metastases. Chemotherapy began with pemetrexed, and the patient died after 2 months.

Case 2. Our second patient was a 59-year-old man, smoker of 15 cigarettes per day, with diabetes mellitus type 2. He was admitted with oedema and had proteinuria at 14g/day, microhaematuria, and preserved renal function. Immunity and complement test results were normal. Virus serology was negative. PSA test was normal. Lung and gastrointestinal tumour markers were negative. Chest x-ray revealed normal pleuropulmonary parenchyma. An ultrasound demonstrated normal kidneys. A renal biopsy was diagnostic of stage I MGN

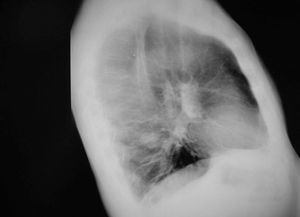

Conservative treatment began with ACE inhibitors and ARBs. At the fourth month of diagnosis, due to lack of response, CsA was started without success. After sixth month, the patient was switched to treatment with chlorambucil and prednisone for eight months with no response, and this treatment was suspended due to leukocytopenia. A year and a half after the biopsy, partial remission was reached (proteinuria: 5g/day) with conservative treatment. After two years, a node appeared in the left lower lung lobe (Figure). Fibre-optic bronchoscopy confirmed stage IV squamous cell carcinoma. Further analyses showed numerous nodules indicative of pleural, bone and liver metastases.

DISCUSSION

In the aetiological analysis of the MGN, in which cases must we be 'aggressive' in screening for malignancy, and to what extent? In case 1, the appearance of MGN and a solid tumour was simultaneous, without clear clinical evidence of cancer. In case 2, the tumour appeared 2 years after the diagnosis of MGN, coinciding with partial remission, which calls into question a causal relationship, because it is more plausible that this was a case of a latent tumour activation caused by immunosuppression.

Approximately 10% of the MGN are paraneoplastic, secondary to lung, prostate and gastrointestinal tumours.1 Lung cancer is the most common tumour type in adult males,2 smokers, and patients older than 65 years. Many authors advocate an aggressive screening protocol in patients with MGN. The relationship between cancer and MGN may be causal or the consequence of immunosuppressant therapy, or it could be just coincidence. The appearance of tumours has been described as many as 5 years after the diagnosis of MGN.3

In recent years, the controversy between idiopathic and secondary causes seems to be somewhat clearer. M-Type phospholipase A2 receptor is associated with idiopathic MGN,4 and the same can be said of anti-aldose reductase and anti-manganese superoxide dismutase, while the absence of IgG4 glomerular deposits suggests a neoplastic process.5 However, these diagnostic techniques are still unavailable in many hospitals.

Our cases showed two distinct patterns of association between MGN and tumours. We believe that attending physicians must pay close attention to these patients from the moment of diagnosis and throughout the patient follow-up period in order to facilitate the early detection of cancers that might affect patient prognosis.

Conflicts of interest

The authors affirm that they have no conflicts of interest related to the content of this article.

Figure 1. Lateral chest x-ray