Living donor kidney transplantation (LDKT) is the best treatment option for end stage renal disease in terms of both patient and graft survival. However, figures on LDKT in Spain that had been continuously growing from 2005 to 2014, have experienced a continuous decrease in the last five years.

One possible explanation for this decrease is that the significant increase in the number of deceased donors in Spain during the last years, both brain death and controlled circulatory death donors, might have generated the false idea that we have coped with the transplant needs. Moreover, a greater number of deceased donor kidney transplants have caused a heavy workload for the transplant teams.

Furthermore, the transplant teams could have moved on to a more conservative approach to the information and assessment of patients and families considering the potential long-term risks for donors in recent papers. However, there is a significant variability in the LDKT rate among transplant centers and regions in Spain independent of their deceased donor rates. This fact and the fact that LDKT is usually a preemptive option for patients with advanced chronic renal failure, as time on dialysis is a negative independent factor for transplant outcomes, lead us to conclude that the decrease in LDKT depends on other factors.

Thus, in the kidney transplant annual meeting held at ONT site in 2018, a working group was created to identify other causes for the decrease of LDKT in Spain and its relationship with the different steps of the process. The group was formed by transplant teams, a representative of the transplant group of the Spanish Society of Nephrology (SENTRA), a representative of the Spanish Society of Transplants (SET) and representatives of the Spanish National Transplant Organization (ONT).

A self-evaluation survey that contains requests about the phases of the LDKT processes (information, donor work out, informed consent, surgeries, follow-up and human resources) were developed and sent to 33 LDKT teams. All the centers answered the questionnaire. The analysis of the answers has resulted in the creation of a national analysis of strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, threats (SWOT) of the LDKT program in Spain and the development of recommendations targeted to improve every step of the donation process. The work performed, the conclusions and recommendations provided, have been reflected in the following report: Spanish living donor kidney transplant program assessment: recommendations for optimization. This document has also been reviewed by a panel of experts, representatives of the scientific societies (Spanish Society of Urology (AEU), Spanish Society of Nephrology Nursery (SEDEN), Spanish Society of Immunology (SEI/GETH)) and the patient association ALCER. Finally, the report has been submitted to public consultation, reaching ample consensus. In addition, the transplant competent authorities of the different regions in Spainhave adopted the report at institutional level.

The work done and the recommendations to optimize LDKT are summarized in the present manuscript, organized by the different phases of the donation process.

El trasplante renal de donante vivo (TRDV) es la opción terapéutica con las mejores expectativas de supervivencia para el injerto y para el paciente con insuficiencia renal terminal; sin embargo, este tipo de trasplantes ha experimentado un descenso progresivo en los últimos años en España.

Entre las posibles explicaciones del descenso de actividad se encuentra la coincidencia en el tiempo con un aumento en el número de donantes renales fallecidos, tanto por muerte encefálica como por asistolia controlada, que podría haber generado una falsa impresión de ausencia de necesidad del TRDV. Además, la disponibilidad de un mayor número de riñones para trasplante habría supuesto un incremento en la carga de trabajo de los profesionales que pudiera enlentecer los procesos de donación en vida. Otro posible argumento radica en un posible cambio de actitud hacia posturas más conservadoras a la hora de informar a pacientes y a familiares acerca de esta opción terapéutica, a raíz de los artículos publicados respecto al riesgo de la donación a largo plazo. Sin embargo, existe una importantísima variabilidad en la actividad entre centros y comunidades autónomas, no explicada por el volumen de trasplante procedente de otros tipos de donante. Este dato, unido a que la indicación de donación renal en vida se realiza de manera mayoritaria en situación de enfermedad renal crónica avanzada (ERCA) y que el tiempo en diálisis es un factor pronóstico negativo respecto a la supervivencia postrasplante, permite concluir que el descenso depende además de otros factores.

Por este motivo, en la reunión anual de equipos de trasplante renal, celebrada en la sede de la Organización Nacional de Trasplantes (ONT) en 2018, se constituyó un grupo de trabajo formado por equipos de trasplante renal, el grupo de trasplantes de la Sociedad Española de Nefrología (SEN) (SENTRA), la Sociedad Española de Trasplantes (SET) y la ONT, con el objetivo de identificar otras causas que condicionaron el descenso de la actividad de este tipo de trasplantes en España y su posible relación con la gestión del proceso de donación de vivo.

El grupo de trabajo diseñó un cuestionario de autoevaluación, que fue cumplimentado por las 33 unidades de trasplante renal de donante vivo activas en España. El cuestionario contiene preguntas sobre las diferentes fases del proceso de donación de vivo: información inicial, estudio del donante vivo e información de los riesgos, consentimiento, recursos humanos (RRHH), nefrectomía, trasplante y seguimiento posterior.

El análisis de las respuestas ha dado como resultado la creación de un análisis de debilidades, amenazas, fortalezas y oportunidades (DAFO) del programa a nivel nacional y ha permitido elaborar recomendaciones específicas dirigidas a mejorar cada una de las fases del proceso de donación en vida. El documento, denominado Análisis de situación del trasplante renal de donante vivo y hoja de ruta ha sido también revisado por un panel de expertos en TRDV, representantes de varias sociedades científicas implicadas (Asociación Espa˜nola de Urología [AEU], Sociedad Espa˜nola de Enfermería Nefrológica [SEDEN], Sociedad Espa˜nola de Inmunología [SEI/GETH]), el Grupo de Trabajo Enfermedad Renal Crónica Avanzada (ACERCA), la Asociación de Pacientes para la Lucha Contra la Enfermedad Renal (ALCER) y sometido posteriormente a consulta pública. Tras incluir las mejoras sugeridas, el documento final ha sido adoptado institucionalmente en el Consejo Interterritorial de Trasplantes (CIT) del Sistema Nacional de Salud.

El trabajo realizado y las recomendaciones para optimizar el TRVD se describen a lo largo del presente artículo, organizados por los diferentes apartados del proceso de donación.

Kidney transplant is the best treatment for chronic kidney failure in terms of survival, quality of life, complications and cost-effectiveness compared to dialysis1–5 and, in the case of living donation, with a low rate of complications for the donor.6,7 Therefore, this procedure is widely used internationally. According to data from the World Observatory on Donation and Transplantation,8 more than 95,000 kidney transplants were carried out in 2018, 36% from living donors. This percentage drops to 28% in the group of countries of the Council of Europe. However, in Spain, the contribution of living donation to the overall transplant activity is 10%.9,10

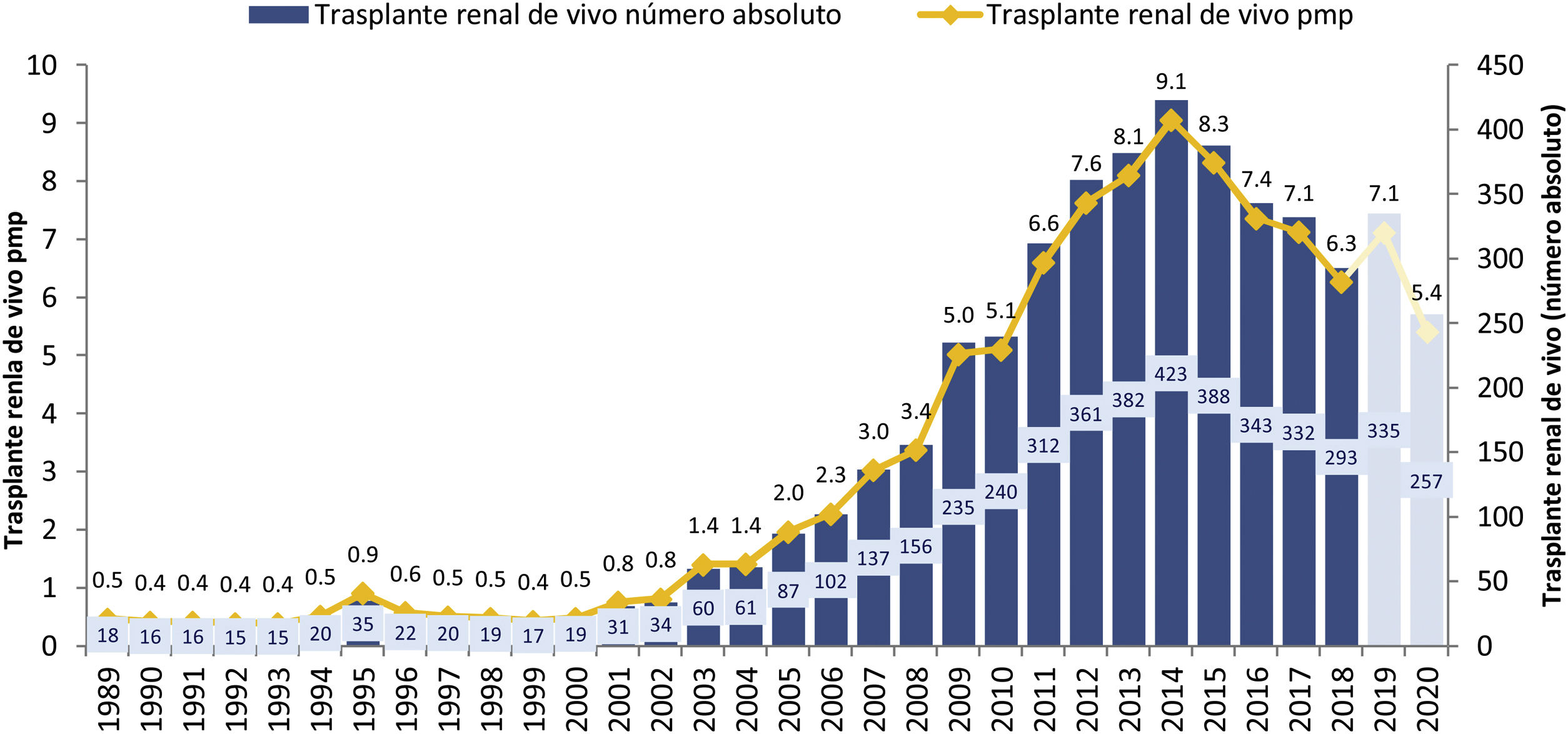

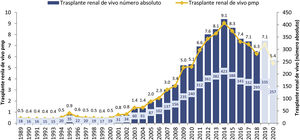

In the first decade of this century, a series of initiatives were carried out by different actors: health authorities (ONT and Autonomous Transplant Coordinations [CAT]), health professionals at the center level, scientific societies and patient associations, with the objective of promoting living donation. These information-based initiatives, with training actions aimed at professionals, development of action protocols and clinical practice guidelines,11,12 implementation of cross-donor and altruistic donation programs13,14 and the living donor registry15 led to a significant increase in the activity of this type of transplant in our country during the period 2005–2014, going from rates below 3 transplants per million population (pmp) to 9 procedures pmp, with figures greater than 400 transplants annual in absolute numbers (Fig. 1). However, as of 2014, the curve has been inverted with a progressive decrease in the activity of TRDV.

Evolution of TRDV activity in Spain (1991–2018).10

An initial analysis of the situation led to the suspicion that the fundamental reason was the increase in the availability of kidneys for transplantation from deceased donors, as a result of the increase in brain-dead donation activity and the extraordinary development of donation in controlled asystole in the last years.10,16 This increase in activity would have contributed, on the one hand, to generating the perception of a decrease in transplant needs on our list, with shorter waiting times. On the other hand, the increase in the number of procedures with increasingly complex donors would have meant a significant workload for transplant teams (and, to a lesser extent, also for transplant coordination, urology and immunology professionals).. If the composition of the transplant teams has not changed, living donation could involve extra work, since in Spain the study and coordination of the living kidney donation process falls, in the vast majority of cases, to in transplant nephrologists.

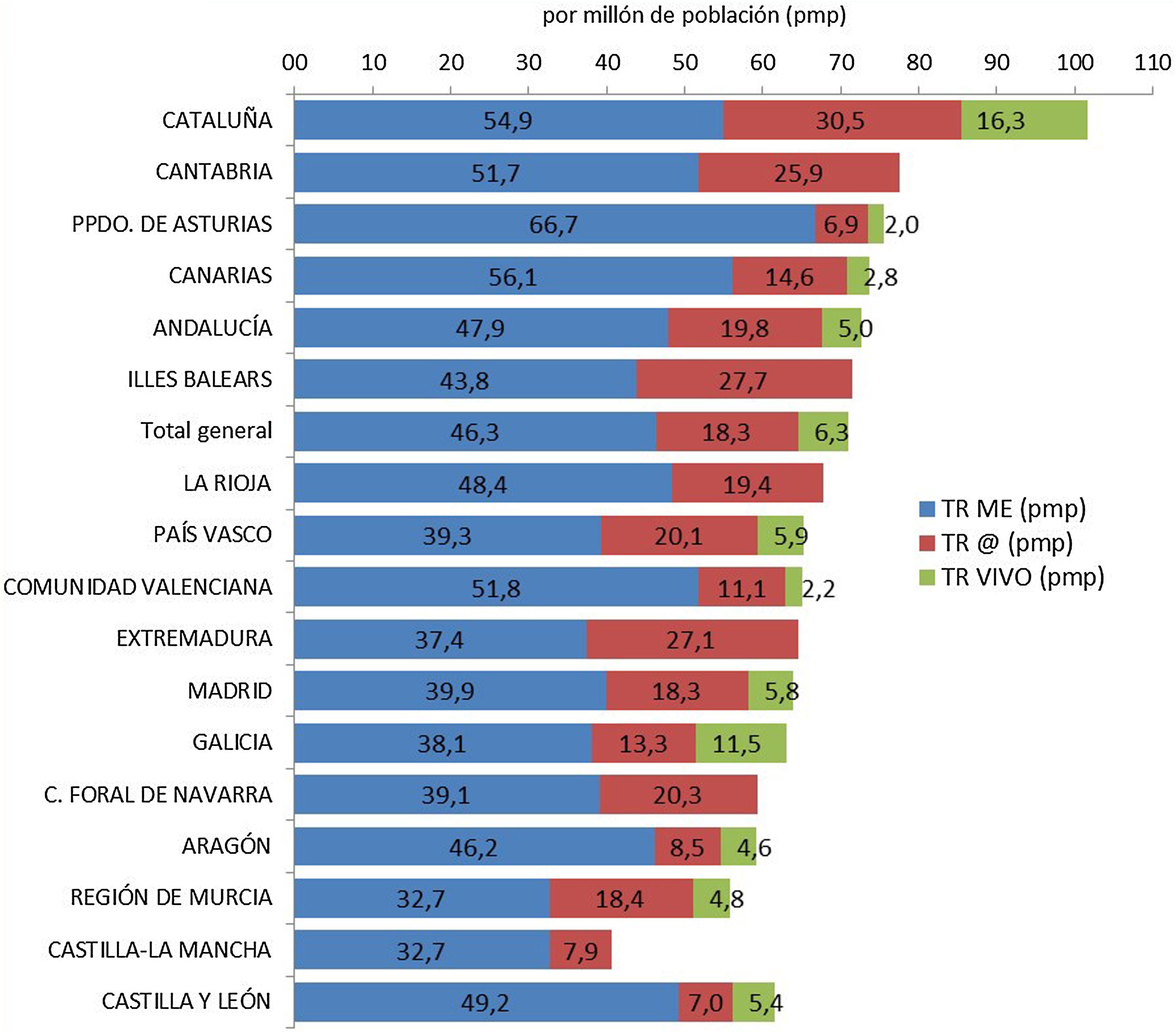

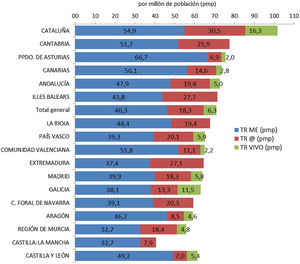

Based on this assessment, and under the premise that the increase in deceased donor transplant activity could have had a negative influence on living donation activity, we have analyzed kidney transplant activity in its different modalities, stratified by autonomous community. Although it is true that the decrease in live-donor activity has occurred in the vast majority of communities, the one with the highest rate of deceased-donor kidney transplants (Catalonia) is also the one that has performed the greatest number of living-donor procedures pmp. In addition, the autonomous communities with a lower rate of kidney transplantation from deceased donors have not met the needs with an increase in living donation activity (Fig. 2).

Kidney transplants by Autonomous Communities (CCAA) of transplant and type of donor pmp in Spain (2018).10

Another reason that could have influenced the decrease in living kidney transplantation is the uncertainty about the long-term safety of this donation, after the publication of the Norwegian and American experiences, although these studies have methodological biases in the selection of the transplant. control population studied, which could justify the increased morbidity and mortality of the donor compared to the matched healthy population.17,18 Recently, the characteristics that make up a higher risk profile compared to another with similar results to the healthy population have been revealed, which allows a better risk assessment to be carried out.19

In this context, the National Strategic Plan for Organ Donation and Transplantation, conceived for the years 2018–2022, identifies as Action number 33: the analysis of the reasons that have determined the reduction in the activity of TRDV and the identification of good practices in the organization and development of the processes of information, evaluation and selection (immunological, nephrological, urological and psychosocial) of the living donor, as well as the surgical procedure, care and follow-up.20

With this objective, the ONT agreed with the kidney transplant teams of our country, at the annual meeting held in 2018, the creation of a working group made up of volunteer nephrologists from the centers with a DRT program, the SET, SENTRA and the ONT itself to carry out an analysis of the situation and detect areas for improvement.

This document summarizes the methodology used for the aforementioned analysis, its results and the recommendations derived to optimize the DLT processes in the centers, which are detailed in the Consensus Document: Situation analysis of living-donor kidney transplantation and roadmap, available on the web pages of the SEN, the SET and the ONT.21–23

MethodologyThe working group designed a self-assessment questionnaire21–23 for the person in charge of the DLT program in each center.

The instrument included closed and open questions, so that the respondents had the opportunity to argue their answers. In order for those responsible for the centers to feel more free in the information provided by their answers, it was guaranteed that these would only be known by the center and by the work group, so that the hospital maintained anonymity in the reports and conclusions. From this project.

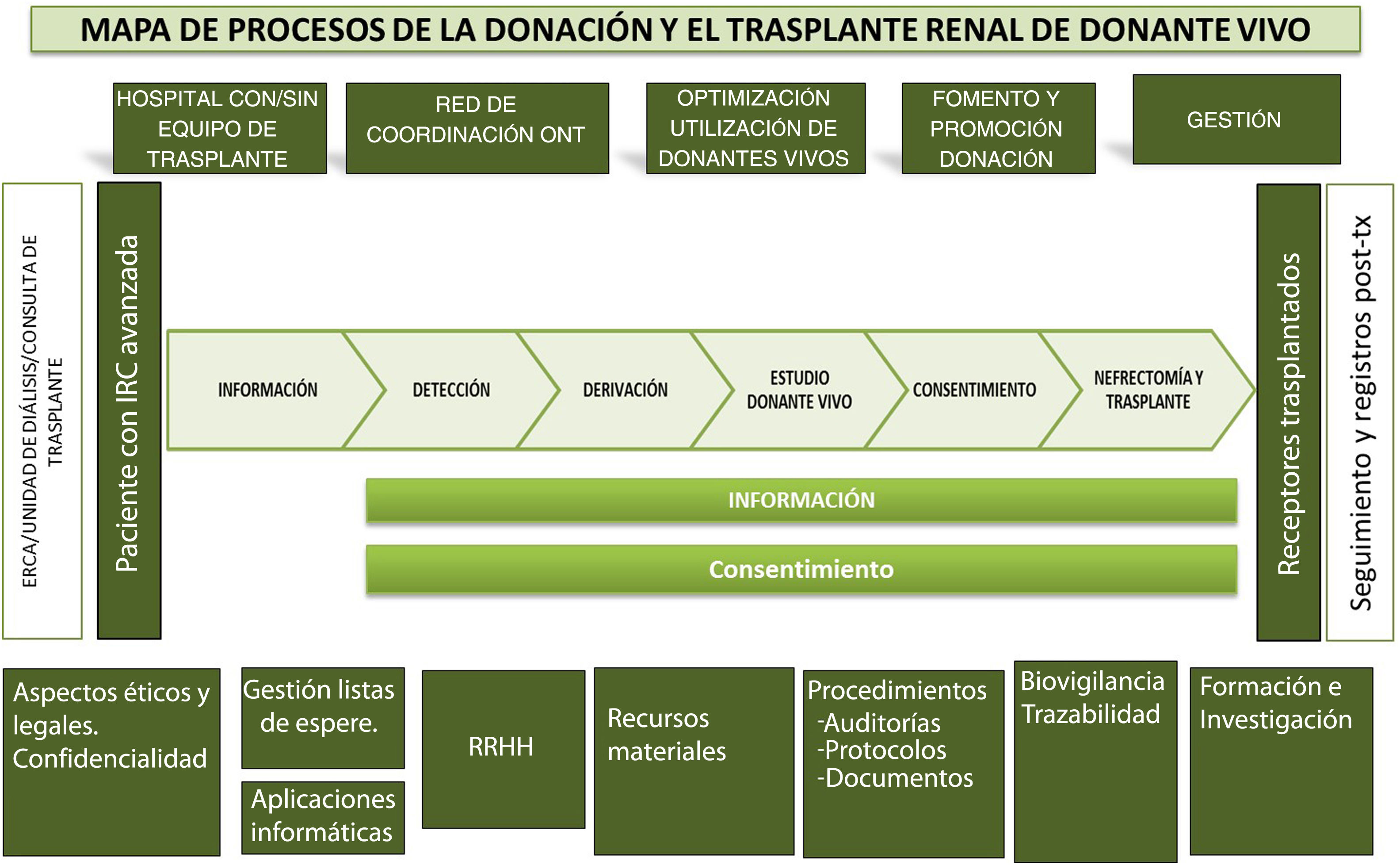

In addition, to facilitate completion of the questionnaire and subsequent analysis, the questions were grouped according to the different phases of the living donation process (Fig. 3):

- 1

Initial information/detection: Type of initial information provided to kidney patients, if this information is protocolized, if a specific time is dedicated, at what time and place it is reported, what is the profile of the professionals who provide the information, if this is offered only to the patient or also to the companions and if they consider that the information they provide is adequate or not.

- 2

Study process: Existence of a figure responsible for the study process, as well as protocols that specify how the management of the studies and the request for tests are carried out, if the study is prioritized because it is a living donor, what actions have been carried out to optimize the study process and what improvement actions the centers propose. Finally, if it is considered that the study time of a living donor in the center is adequate.

- 3

Consent to donation: Aspects related to the information provided for the signature of the consent to the extraction of a kidney, the performance of the Healthcare Ethics Committee (CEAS) and that of the court of first instance.

- 4

HR: Number, dedication and experience in DLT of the health professionals of the nephrology, urology, nephrology nursing and transplant coordination units, as well as other tasks carried out by these groups and if the availability of HR is considered adequate to carry out a TRDV program. Due to the characteristics of the study, the important dedication of other professionals who participate in different sections of the donor study, such as those belonging to immunology services, psychiatry/psychology, radiodiagnosis, internal medicine, etc., has not been explicitly contemplated, but it will be reflected in the areas for improvement proposed by the centers for improvement in the study process.

- 5

Nephrectomy, transplant and follow-up: Questions related to the capacity of hospitals to adapt to the activity of living donation and the prioritization of the process in the center.

- 6

Final questions: Opinion about the activity of TRDV in the hospital; if it is considered appropriate and what is the attitude of professionals in the hospital and peripheral centers towards living donation. Finally, possible improvement actions that have been detected, both locally and in general.

Map of the kidney transplant process with a direct living donor.21–23

The analysis of the answers to the questionnaire was carried out from two different perspectives:

On the one hand, a descriptive analysis of the quantitative variables was carried out, using frequency measures for the categorical ones and dispersion measures for the quantitative variables, for which SPSS version 25 (SPSS Inc., Chicago IL., USA) was used.) for statistical analyses. In addition to the self-assessment questionnaire, the National Registry of Donation and Transplantation (CORE) was used to obtain kidney transplant activity data (overall and stratified into living donor and deceased donor) for the period 2013–2017, and to be able to analyze the responses along with information on transplant activity.

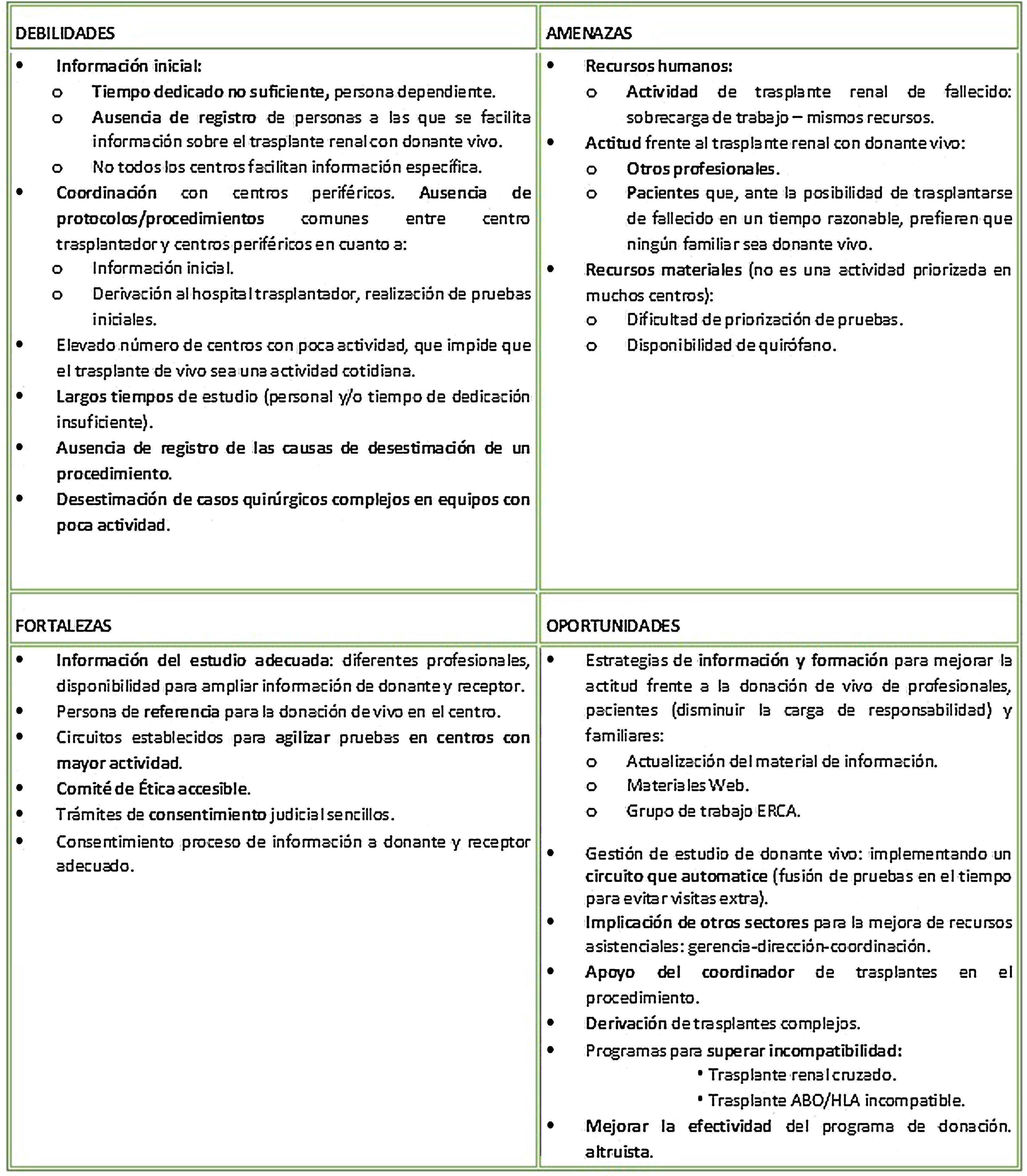

On the other hand, based on the open responses, a SWOT analysis (Fig. 4) of the TRDV program at the national level was prepared, identifying the weaknesses, threats, strengths and opportunities of the process as a whole.

SWOT analysis of the national TRDV program.21–23

The complete analysis of the responses by the working group resulted in the elaboration of a series of recommendations and actions separated by each phase of the TRDV process.

The complete study was included in the document Situation analysis of living donor kidney transplantation and roadmap, which was also reviewed by a group of professionals who are experts in living donation, health policy, and ACKD patients.

Subsequently, the document was submitted to representatives of the Scientific Societies SEDEN, AEU, SEI/GETH, the ALCER patient association and finally submitted to public consultation, reaching a broad consensus and being institutionally adopted by the Interterritorial Transplant Council of the National System of Health in November 2020.

The recommendations developed for each of the sections of the process are summarized below:

Development of recommendationsInitial informationThe ideal time to detect a possible living donor for a kidney transplant recipient is at the time of consultation at the ACKD unit.

To improve the detection of a possible living donor, this option should be adequately informed when renal replacement therapy options are explained to patients and relatives.

Information about the DRT option should be reinforced in the waiting list consultation, at the start of dialysis, and performed periodically in those patients, candidates for transplant, who have preferred to wait for a transplant from a deceased donor that has not been performed.

It is necessary to establish a specially dedicated multidisciplinary team (doctor/nurse), with adequate training to cover the informative aspects.

It is necessary to have rigorous, up-to-date information material that is easy to understand and agreed upon at the national level, to deliver to the patient and their loved ones.

Although the vast majority of centers report that they inform on a regular basis, none of them keep a record of the patients to whom this therapeutic option is explained. It is necessary to know the volume of kidney transplant candidate patients who receive information about the DRT option in order to determine the real indication for this type of transplant in Spain.

On the other hand, not all centers have a protocol for providing information, so both the way of approaching it and the time it is provided is “person-dependent” in hospitals. In this sense, the ACKD group of the SEN has launched a quality accreditation system for advanced chronic kidney disease units, which incorporates, within its mandatory standards, the development of information protocols about the donation of I live between the different options for renal replacement therapy and the registration of this information.24

On the other hand, there is a significant volume of patients treated in non-transplant centers (both hospitals and dialysis centers) and the perception of the information provided in them is variable, which indicates a lack of adequate coordination between these centers and your referral hospital.

Study processThe study process must be able to be carried out, on average, in a period not exceeding 12 weeks, with the support of the hospital institution.

The study process must follow a previously established protocol, which encompasses the organization of the process, how it begins, the roles of the personnel involved, including the person in charge of the program, the tests to be carried out, support from other services involved (such as immunology, radiology, etc..) and a set schedule.

Non-transplant centers should collaborate in the initial phases of the study process to speed up the process itself and to avoid overloading the transplant center with work, although a coordinated procedure with the transplant center is recommended.

The study time of a living donor should be similar in a transplant and non-transplant hospital, regardless of whether the non-transplant hospital performs some or all of the tests.

Monitoring of the study procedures started and how many do not end in transplant is recommended, to detect areas for improvement.

Regarding the process of studying the living donor, there is significant motivation on the part of the professionals in charge of it; however, although the centers follow a diagnostic test protocol that they must perform, the presence of a procedure that automates the requests facilitates the performance of tests, thus shortening the study time. In this sense, teamwork and the support of other services, such as immunology, radiodiagnosis, psychology, etc. is essential to optimize this phase of the process.

With regard to the reasons for rejection, few centers exhaustively collect the reasons why a living donor procedure does not go ahead, something essential to establish areas for improvement.

Consent to donationUp-to -date informative materials must be created, agreed upon and adapted to the conditions of the donor, to facilitate the understanding of the information.

It is necessary to have a specific informed consent document, which includes not only the peculiarities of nephrectomy for donation and transplantation, but also the risks associated with being a single kidney, in relation to cardiovascular risk and CKD.

The information must be provided by a team of at least two professionals.

The consent process, which encompasses the information that the donor receives about the specific risks of the procedure throughout the evaluation process, as well as the evaluation procedure by the CEAS and the court appearance, is clear and well established. There is, however, variability in the type of consent that is provided for signing, so work must be done to unify it, so that the donor has the same information regardless of their place of residence.

On the other hand, although it is not a direct conclusion of the results of the questionnaire, it is important to assess the support in the information, both by the properly trained nursing staff, as well as by patients and donors who have lived the TRDV experience. The latter, through their testimonies, can help facilitate good emotional management of the process, which is sometimes experienced with a high degree of anxiety on the part of the families.

Human resourcesThe number of human resources assigned to the TRDV must be adapted to the kidney transplant activity carried out by the center with the support of the hospital institution itself.

The professionals assigned to the TRDV must have a specific time dedicated to it. In addition, each professional must be properly trained in their skills (nephrology, urology, nephrology nursing, immunology, etc.) to properly attend to each of the sections that make up the DRT process: from detection to nephrectomy and care later.

In the transplant centers there should always be a person responsible for the entire living donation program, with a professional profile that allows him or her to organize and manage all the tasks derived from it. This professional will have support staff to coordinate complementary examinations, specialist visits and administrative procedures.

Regarding HR, for the different phases of the living donation process there are professionals responsible for them, but it has not been possible to determine if there is a person who coordinates all the tasks derived from this therapeutic act. It is important to define this figure at the hospital level with a profile and assignment of tasks to facilitate the coordination of processes.

Regarding other professionals who participate in the process, a dispersion is observed that makes it very difficult to establish a direct relationship between the number of HR and activity, although it is true that hospitals with greater activity dedicate a greater number of professionals and these have more experience time. On the other hand, the increase in the number of transplants from deceased donors that Spain has experienced globally has meant an increase in the workload in the centres, so it is possible that the dedication to living donation has been diminished. With regard to the functions of the hospital transplant coordinator, they vary depending on the center, playing a logistical support role in the vast majority of cases.

Availability of operating roomsA mechanism should be established to facilitate the availability of the operating room when there is a living donor procedure.

When the time comes for the transplant, not all centers have the facility to choose an operating room date, as it is not a prioritized activity in the center. This circumstance lengthens the time of the living donation process and can be a determining factor in the center’s activity. The availability of the operating room can materialize, for example, on fixed days of surgery or programming of the operating room at a specific time.

FinancingThis work has not received any funding.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: de la Oliva Valentín M, Hernández D, Crespo M, Mahillo B, Beneyto I, Martínez I, et al. Trasplante renal de donante vivo. Análisis de situación y hoja de ruta. Nefrologia. 2022;42:85–93.