Dear Editor,

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an inflammatory disease with systemic effects.1 At least 50% of all patients present signs of nephropathy during their illness, and nearly half present diffuse proliferative nephritis.2 Tubulointerstitial nephritis as an isolated histological lesion is infrequent in SLE patients, and to our knowledge, few published cases exist in the literature.1-2

We present the case of a 67 year old female patient diagnosed with arterial hypertension. She was admitted with a sensation of nausea, urinary infection and anaemia. Laboratory analysis: Ht 27.8%; Hb 9.5g/dl. ESR 63mm. Urea 182mg/dl; creatinine 4.7mg/dl; calcium 9mg/dl; phosphorus 4.2mg/dl and total proteins 9g/dl. Creatinine clearance rate (Cockcroft-Gault formula): 17.73ml/min. Immunoproteins and complements were normal. Kappa chains 774mg/dl, Lambda chains 392mg/dl. In the proteinogram, we observed a wide-base peak in the Gamma region with increased IgG (193%) and light Kappa (191%) and Lambda chains (180%). K/L index = 1.97. Light chains in urine: Kappa chains 13.7mg/dl (0-0.7); Lambda chains 6.880 (0-0.39). A bone marrow aspiration and biopsy was performed, with a normal result. TSH: 4.85μUI/ml, free T4 1.03ng/fl; anti-TPO antibodies 22.5UI/ml; antithyroglobulin antibodies 115.3UI/ml. PTH: 110pg/ml. Urine (test strip): Proteins 25mg/l; sediment: abundant leukocytes. Tumour markers: normal. Viral serology: negative. Autoantibodies: ANA+, anti-DNApositive.

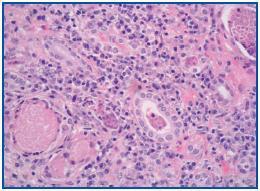

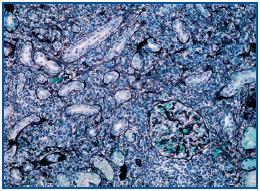

A percutaneous renal biopsy was performed (with 18 verifiable glomerules): No significant glomerular alterations. The tubules presented dilated lumens occupied by granular cylinders containing cellular detritus. Tubular atrophy foci and hyaline cylinders were present (figure 1). In the interstitium and vessels, abundant lymphocyte infiltrates, mostly from plasma cells that broaden the interstitium, provoke the collapse and disappearance of tubules as well as the erosion and epithelial infiltration of basement membranes (figure 2). With immunofluorescence, we observed granular deposits in the arterial walls of complement C¿3 (++) and tubular cylinders of IgA (++). Using immunohistochemical techniques, we found linear deposits of light kappa chains on tubular basement membranes. Anatomical-pathological diagnosis was inflammatory tubulo-interstitial nephritis. This morphological profile appears in 10% of patients who suffer plasma cell dyscrasias, most frequently in myeloma with a predominance of light K chains.

In most cases of SLE, the glomerular condition is the main histological lesion. An isolated condition affecting the tubule and interstitium is rare.

We ruled out other causes of tubulointerstitial nephritis, such as drugs or toxins. The intense presence of tubulointerstitial damage in absence of significant glomerular damage supports the theory that immune complexes are bound to one or more tubulo-interstitial autoantigens that are not expressed in the glomerulus. The underlying mechanism represents in situ formation of immune complexes as a result of circulating autoantibodies binding to antigens.3 Although the exact mechanism is unknown, it is possible that its virulence depends on the structural characteristics of the antigenantibody union region, the isotope, and the isoelectric charge.3 A recent study describes how the union of T CD4+ cells with antigens in the glomerular basement membrane can begin the glomerular damage that will trigger glomerulonephritis. It is possible that a similar mechanism might participate in the pathogenesis of tubulo-interstitial nephritis in such a way that cell immunity damages tubular antigens; this would trigger an interstitial condition, as in other interstitial nephropathies.4

The treatment of tubulo-interstitial nephritis in SLE is not wellestablished, but it seems not to require immunosuppressant therapy, and it might respond to low doses of oral steroids.5

Figure 1.

Figure 2.