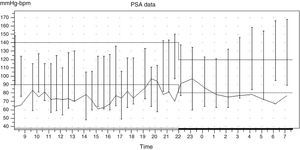

The patient is a 22-year-old quadriplegic male with trauma was referred to us due to hypertensive emergency with blood pressure values of 250/150mmHg associated with headache, blushing, perspiration, bradycardia and somnolence. Two years earlier patient had trauma that caused tetraplegia due to craneoencephalic and vertebro-medullary injury resulting in C5 fracture and anterior cervical arthrodesis with complete medullary motor C5 and sensitive C4 lesions. The patient was dependent on others to perform everyday activities and required intermittent urinary catheterization. At medical examination, the patient was conscious and oriented, eupneic in resting position with normal skin and mucosae colouration. Heart sounds were regular at 60 heartbeats per minute without murmurs or audible extra sounds; normal respiratory sounds. Abdomen was soft, nontender, without masses and palpable organomegaly, with no abdominal murmurs. Palpable and symmetric pedial pulse in both lower extremities was noticed. No oedemas were found. A summary of blood tests: haemogram; haemoglobin 13.2g/dl, haematocrit 37.1%, leukocytes 7.200/mm3, platelet count 307.000/mm3; biochemistry: glucose 65mg/dl, urea 37mg/dl, creatinine 0.63mg/dl, GF >60ml/min/MDRD4, cholesterol 140mg/dl, LDL 73mg/dl, Triglycerides 60mg/dl, AST 28U/l, ALT36 U/l, GGT 29U/l, sodium 140meq/l, potassium 4.7meq/l, calcium 9.4mg/dl, phosphate 4.3mg/dl urine screening without alterations or sediments; 24-h urine sample collection: sodium 262meq/24h, ClCr 187.9ml/min, proteins 198mg/24h, albumin 15.6mg/24h; endocrine screening: TSH 3.3mcIU/ml, cortisol 13.2mcg/dl, 24h urine free cortisol 41.8mcg/24h. Catecholamine and metanephrine in urine were normal. Echocardiogram showed no dilation or hypertrophy of left ventricle with preserved systolic function and normal wall motion. No dilation in right cavities; no valve abnormalities; no pericardial effusion. Normal Eye fundi; chest X-ray: no abnormal findings; normal kidneys by ultrasound. A 24-hour outpatient blood pressure (BP) monitoring was performed with the following results: average BP while awake 125/86mmHg with average heart rate (HR) 75b/m. Average BP during sleep was 144/74mmHg with average HR of 80b/m. The variation between the average BP between wakefulness and sleep state was of 19/6mmHg (15%/9%). The variation of the average HR between wakefulness and sleep was of 5b/m (7%). The following values of BP were recorded: 150/97at 9:40p.m.; 158/84, 154/72, 166/95mmHg at 4:00–5:00a.m. It could not be demonstrated that blood pressure elevation occured prior to the procedure of bladder catheterization (when bladder was replete). The patient mentioned that around 5:00–6:00a.m., he usually undergoes perspiration and headache that wakes him up, which disappear after the catheterization (Fig. 1). The first suspicion was autonomic dysreflexia (AD); other possible causes assessed were primary hypertension (AMPA and Holter results did not show continuous high BP), pheochromocytoma (catecholamine and methanephrine within normal boundaries), migraine headache (he only mentioned headache coinciding with episodes of high BP) and the presence of brain tumours (though ophthalmoscopic examination was normal, but no imaging tests were performed to rule out tumors). Therefore we believe this is a case of AD in a patient with medullary injury, probably caused by bladder stimulation and, as a consequence, by blood pressure rising. AD is an acute syndrome due to excessive and uncontrolled sympathetic response produced in patients with spinal cord injuries.1–3 It usually appears after the medullary injury and affects between 48% and 90% of patients with medullary lesions affecting T6 or higher. As far as the pathophysiology, after spinal cord lesion, the sympathetic modulation of impulses travelling from the bladder zone to the brain through the spine is lost. In patients with injuries above T6, medulla afferent reflexes stimulate a sympathetic response, which originates in the mid-lateral cells column which are still operational despite the medullary injury; this is associated to an inadequate supraspinal control because the parasympathetic stimulus cannot travel through the injured medulla. The results include: hypertension as a sympathetic response, and bradycardia, perspiration, piloerection and headache a parasympathetic response.4,5 As far as treatment, first, avoid pharmacological treatment, and apply postural changes to lay the patient in supine position, removal of tight-fitting garments which perpetuate bladder stimulus. The search and elimination of the sympathetic stimulus is crucial for the case to be controlled; it must be initially addressed to discard its origin in bladder and rectum, which are responsible for triggering AD in more than 80% of the crises.6 It must be checked that the bladder catheterization is permeable, that it is not causing injuries, that it is not painful when removed, etc. A second most frequent cause of hypertensive crises must be taken into account, i.e., gastrointestinal tract stimuli, such as constipation due to faecal impaction.7,8 Other causes, though less frequent, are cutaneous stimuli, menstruation, trauma, etc. (Table 1). In such a case that the triggering cause cannot be eliminated, a rapid-acting oral pharmacological treatment should be initiated. The most commonly used drugs are nifedipine and nitrites. Alpha-blockers (phenoxybenzamine) and alpha-agonists (clonidine) are also effective drugs in an AD crisis; other drugs used are hydralazine and, if necessary and under monitoring, IV sodium nitroprusside. Some studies advise the use of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEi) as a second option. Finally, alpha-blockers such us doxazosin can be used as prophylaxis and, therefore, as baseline treatment in such crisis in patients with recurrent episodes that cannot be prevented.9,10 AD is a specific complication in patients with medullary injury that can involve risk of death, therefore a hypertensive crisis must be known and suspected of in this group of patients. Its management will be focused on its detection and avoiding the triggering cause of hypertensive crisis.

Possible AD causes.

| Stimuli that can trigger AD: |

| - Bladder distension, vesical lithiasis, urinary sepsis, traumatic catheterization, cystoscopy, urodynamic testing |

| - Rectal distension, faecal impaction, complicated haemorrhoids, rectoscopy/colonoscopy, gastroduodenitis, gastroduodenal ulcer, “Silent” acute abdomen, gastroscopy, gallstones |

| - Tight garments, footwear or orthosis |

| - Menstruation, pregnancy, particularly during labour, vaginitis |

| - Epididymitis, ejaculation |

| - Pressure ulcers, burns |

| - Traumas: fractures, dislocations and sprains, heterotopic ossification |

| - Lymphangitis, deep vein thrombosis |

| - Surgical procedures |

Please cite this article as: Toledo-Perdomo K, Viña-Cabrera Y, Martín-Urcuyo B, Morales-Umpiérrez A. Crisis hipertensiva en paciente con lesión medular. Nefrologia. 2015;35:329–331.