Around the 1970s in Canada, policies to promote health began to take shape when the Ministry of Health and Welfare, led by Marc Lalonde, noted the public health system's inability to ensure the health of the population on its own, taking into account the high costs involved and the limited results obtained with lifestyle changes. Subsequently, these conclusions were gathered at the First International Conference on Health Promotion (1986),1 where the Ottawa Charter was drafted, which impacted on the development of the concept of health promotion; this concept “is the process of enabling people to increase control over, and to improve their health; considering that to reach a state of adequate physical, mental and social well-being, an individual or group should be able to identify and to accomplish their aspirations, to satisfy needs, and to change or cope with the environment”.1

Subsequent conferences in Adelaide (1988), Sundsvall (1991), Jakarta (1997), Mexico City (2000), Bangkok (2005) and Nairobi (2009) continued to emphasise the need to develop public policies to strengthen action and strategies aimed at making people to increase control over their health, and with equity in the access to health, and provide the means to enable the entire population to maximise their health potential.

Finally, at the 8th Global Conference on Health Promotion held in Helsinki (2013),2 the promotion of health was said to be a fundamental right of every human being, as well as a factor that determines quality of life, which encompasses physical and emotional well-being in the face of transmissible or non transmissible diseases or any other health threat.2

Within this context, the concept of health literacy was developed. The WHO (2013)3 adopts the following definition, developed by Health Literacy Europe's working group: “Health literacy is based on general literacy and encompasses people's knowledge, motivation and competences to access, understand, evaluate and apply information on health in order to make judgements and make decisions concerning healthcare, disease prevention and promotion of health to maintain and improve quality of life during their life time.”3,4

Health literacy is a concept that is closely related to the capacity for effective acquisition of knowledge, skills and abilities originated from health education, and the autonomy to apply what has been acquired to one's own care and the care of those close to them. Literacy therefore represents a new concept that refers to education on healthy behaviours, and is a step prior to patient empowerment for making decisions on the management of one's own health and illness.5

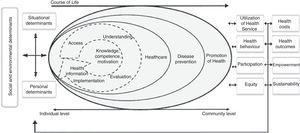

Considered by the WHO as a social determinant, health literacy does not depend exclusively on individual capacities, but on the interaction between demands on the health system and individual abilities, which affect healthy habits and the effective use of the health system. As a result of the project funded by the European Commission, the European Health Literacy Survey (HLS-EU, 2012),4 and following a comprehensive systematic review of the use of the term literacy and related descriptions, a model was proposed to define the concept of health literacy throughout life, which considers three levels of action: care, disease prevention, and health promotion, to which four methods of processing relevant health information must be applied (accessing, understanding, appraising and applying)4,6 (Fig. 1). Thus, in addition to improving patients’ individual capacities, it is necessary to create a physical and social environment in healthcare facilities that is accessible and easy to use.7

Model of the health literacy concept proposed by HLS-EU (2012).5

Health literacy has a direct impact that is evident in vulnerable groups such as the elderly, polymedicated patients, immigrants and the chronically ill. A low level of health literacy may lead to a poor understanding of information about treatments, poor knowledge about chronicity and late detection of diseases, as well as medication errors, misuse of healthcare services and a higher rate of morbidity and hospital admissions.8–10

It would therefore be worth improving the quality and accessibility of information, eliminating structural barriers to provide healthcare and promoting communication skills among professionals that enhance, rather than inhibit, community and patient-association involvement in healthy behaviours.7

Health literacy and advanced chronic kidney diseaseIn moderate or severe renal disease, the prevalence of inadequate health literacy ranges from 5% to 60% depending on the studies and socio-demographic variables considered.11–14 A systematic review, which identified six studies that met the inclusion criteria (a validated measurement of literacy and glomerular filtration), found a combined prevalence of 23% as regards inadequate health literacy in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease (ACKD).15 Low health literacy scores are associated with torpid outcomes and disease progression,16,17 with low glomerular filtration rate11,14 and increased likelihood of a prior clinical history of cardiovascular disorders associated with hypertension and diabetes.14

In dialysis patients, the highest scores in health literacy are associated with behaviours that promote adherence and lower treatment costs.18 The relationship between health literacy and treatment adherence is modulated by the patient's knowledge of the disease, i.e. adequate health literacy promotes greater knowledge of kidney disease and favours adherence-to the treatment.9,19

In this regard, the doctor–patient relationship is both significant and relevant. Some studies indicate that the knowledge about kidney failure and treatment options increases as kidney disease progresses as the number the patient's visits to his/her nephrologist increase.20 The same study shows that integrated ACKD care systems that include psychosocial and multi-professional support (Canada) provide a better level of literacy than non-integrated systems (USA).

In kidney transplantation, between 60% and 90% of patients show adequate levels of health literacy.8,21,22 Improving health literacy in kidney transplant patients leads to parallel improvements in graft function, while lower rates of post-transplant health literacy have been associated with higher levels of serum creatinine.22 Moreover, patients with low levels of health literacy are less often assessed for placement on a transplant list.12,23

Improving health literacy in transplant patients helps to promote healthy behaviours, such as adherence to immunosuppressive therapy and increased physical activity.16

In patients with chronic kidney disease, interventions aimed at increasing health literacy should consider the use psychoeducation programmes that provide feedback on what has been learned.22 Among these programmes, educational materials must be developed and disseminated to patients in relation to cardiovascular disorders and risk factors for diabetes, adapted to the stage of renal disease. Likewise, nephrologists and healthcare professionals should be trained to detect signs of poor health literacy in patients.8 Particularly in patients with advanced stage of the disease literacy will help to gain knowledge on the treatment options for ACKD, types of dialysis, and actions to be taken before a kidney transplant.16,22 Increasing knowledge about chronic kidney disease in relation to health literacy may improve patients’ self-care capacities, lead to an effective use of the health system, and improve the quality of doctor-patient relationships.15

It should also be noted that health literacy depends not only on individual capacities but also on interaction with the healthcare environment. This requires an interdisciplinary and multi-sector approach, with interventions on patients and the general population to increase their health literacy, thereby simplifying accessibility to the healthcare system in a manner that is suitable to all cultural and social contexts, improving the quality of the information transmitted, and surpassing the traditional schemes of health education.6

Please cite this article as: Costa-Requena G, Moreso F, Carmen Cantarell M, Serón D. Alfabetización en salud y enfermedad renal crónica. Nefrología. 2017;37:115–117.