Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is highly prevalent among patients on haemodialysis and leads to a poorer prognosis compared to patients who do not have said infection. Treatment with interferon and ribavirin is poorly tolerated and there are limited data on the experience with new direct-acting antivirals (DAAs). The aim of this study is to retrospectively analyse the current prevalence of HCV infection and efficacy and safety results with different DAA regimens in the haemodialysis population of 2 hospital areas.

This is a multicentre, retrospective and observational study in which HCV antibodies were analysed in 465 patients, with positive antibody findings in 54 of them (11.6%). Among these, 29 cases (53.7%) with genotypes 1 and 4 were treated with different DAA regimens, including combinations of paritaprevir/ritonavir, ombitasvir, dasabuvir, sofosbuvir, simeprevir, daclatasvir and ledipasvir, with/without ribavirin. Mean age was 53.3±7.9 years, 72.4% of patients were male and the most important aetiology of chronic kidney disease involved glomerular abnormalities. In 100% of cases, a sustained viral response was achieved after 24 weeks, regardless of DAA regimen received. Adverse effects were not relevant and no case required stopping treatment. In 15 cases, ribavirin was combined with the DAA. In these cases, the most significant adverse effect was anaemic tendency, which was reflected in the increase of the dose of erythropoietin stimulating agents, although none required transfusions.

In summary, we conclude that new DAAs for the treatment of HCV in haemodialysis patients are highly effective with minimal adverse effects; it is a very important advance in HCV management. These patients are therefore expected to have a much better prognosis than they have had until very recently.

La infección por el virus de la hepatitis C (VHC) es muy prevalente entre los pacientes en hemodiálisis y condiciona un peor pronóstico respecto a los que no la padecen. El tratamiento con interferón y ribavirina es mal tolerado y existen pocos datos sobre la experiencia con los nuevos antivirales de acción directa (AAD). El objetivo de este trabajo es estudiar retrospectivamente la prevalencia actual de la infección por el VHC y los resultados de eficacia y seguridad con distintas pautas de AAD en la población en hemodiálisis de 2áreas hospitalarias.

Estudio multicéntrico, retrospectivo y observacional en el que se analizan los anticuerpos frente al VHC en 465 pacientes, entre los que 54 de ellos eran positivos (11,6%). Entre estos, 29 casos (53,7%) con genotipos 1 y 4 fueron tratados con distintas pautas de AAD, que incluían combinaciones de paritaprevir/ritonavir, ombitasvir, dasabuvir, sofosbuvir, simeprevir, daclatasvir y ledipasvir, con/sin ribavirina. La edad media era de 53,3+7,9 años, el 72,4% eran varones y la causa más importante de la enfermedad renal crónica eran las alteraciones glomerulares. En el 100% de los casos se obtuvo una respuesta viral sostenida a las 24 semanas independientemente de la pauta de AAD recibida. Los efectos secundarios fueron poco relevantes y ningún caso precisó suspender el tratamiento. En 15 de ellos, se asoció ribavirina a los AAD. En estos casos, el efecto adverso más destacable fue la tendencia a la anemización, reflejada en el incremento de la dosis de agentes estimulantes de la eritropoyesis, aunque ninguno precisó transfusiones.

En resumen, concluimos que los nuevos AAD para el tratamiento del VHC en pacientes en hemodiálisis presentan una gran eficacia, con mínimos efectos secundarios, y constituyen un avance muy importante en su manejo, con lo que cabe esperar un pronóstico mucho mejor que el que presentaban hasta muy recientemente.

Chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is a serious health problem that affects more than 170 million people worldwide1–3 and may cause liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. The prevalence of HCV in haemodialysis patients is even greater. Data from the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS) show a very wide range of prevalence among the different countries studied, which in some countries such as Spain reaches as high as 8.9%.4 Moreover, the survival of infected patients decreases with respect to those without the infection.5–7

At the beginning of this century, the combination of pegylated interferon and ribavirin became the standard for treatment for HCV infection.8–10 However, the adverse effects of interferon treatment in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD), potentiated by the ribavirin treatment together with their poor response,10 have proven a major limitation for their widespread use. The recent development of antiviral agents that act directly on viral replication (direct-acting antivirals [DAA]) has completely changed the prognosis of the infection, achieving a sustained viral response (SVR) of over 90% among the general population.11–15 Experience with DAAs in HCV-positive haemodialysis patients is scant, and is related to small patient series. Nevertheless, the results are very promising, reaching an SVR in the vast majority of patients.16–20

The aim of our study is to analyse the current prevalence of HCV infection in the haemodialysis units of two hospitals and their affiliated sites, and to assess treatment response with different DAA regimens.

Materials and methodsA multicentre, retrospective, observational study, in which we analysed all prevalent haemodialysis patients belonging to two hospital areas in Madrid (Spain). Patients with HCV antibodies were identified, and those treated with DAAs were separated from those who had received no specific treatment. HCV antibody detection was performed using a chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay on an Architect i4000 sr autoanalyser (Abbott, Chicago, IL, USA).

All treated patients had previously undergone impulse elastography (FibroScan), with results expressed in kilopascals (KPa) when the HCV-RNA (polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and HCV genotype were determined. The viral load, HCV-RNA (PCR), was determined using a quantitative assay (Cobas Ampliprep/Cobas Taqman HCV [Roche]) and expressed in IU/mL (quantitation range between 15 and 7×107IU/mL). The HCV genotype was determined with the HCV GT CTLS assay on the Cobas 4800 system (Roche).

The following were initially recorded in all cases: personal data, history of comorbidities, time on renal replacement therapy with dialysis or transplant and laboratory tests (haemoglobin, haematocrit, platelets, INR, aspartate aminotransferase [AST], alanine aminotransferase [ALT], gamma-glutamyl transferase [GGT] and bilirubin). Post-treatment laboratory results, management of anaemia during follow-up and treatment-related adverse effects were recorded in patients treated with DAAs. Epoetin and darbepoetin doses were recorded in IU/week. A conversion factor of 1:200 was applied to compare the epoetin dose (IU) with the darbepoetin dose (mcg) as indicated in the drug's Summary of Product Characteristics, so the darbepoetin dose expressed in mcg was multiplied by 200.

Treatment regimens were based on the recommendations of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) when the patient was referred to the Hepatology clinic. Data collection commenced in February 2015. The treatment regimen for patients with genotype 4 included the combination of paritaprevir (150mg)/ritonavir (100mg) and ombitasvir (25mg) in a single daily dose (COMBO 2D), together with ribavirin (200mg/day); for patients with genotype 1b, COMBO 2D was combined with dasabuvir (250mg) twice daily (COMBO 3D); patients with genotype 1a were treated with the COMBO 3D regimen combined with ribavirin; one patient was treated with a sofosbuvir (400mg) and ledipasvir (90mg) regimen (Harvoni®); another with the combination of sofosbuvir (400mg) and simeprevir (150mg); and another with the combination of simeprevir and daclatasvir (60mg). A total of 15 cases received ribavirin at a dose of 200mg/day. Treatment was maintained for 12 or 24 weeks for all regimens, according to the recommendations of the Hepatology department, based on AASLD guidelines. The patient was considered to have an SVR when the HCV-RNA (PCR) was negative 24 weeks after completion treatment.

Reasons to decide non-treatment were: short life expectancy, age over 80 years, undetectable HCV-RNA (PCR), genotype 3 and clinical stability with no changes in laboratory tests or abnormalities on the FibroScan.

Statistical analysisQuantitative variables are expressed as a mean and standard deviation, and compared using the Student's t-test. Qualitative variables are expressed as percentage and compared using the Chi-square test. Differences were considered to be significant when p<0.05. SPSS version 17 (Chicago, IL, USA) was used for all calculations.

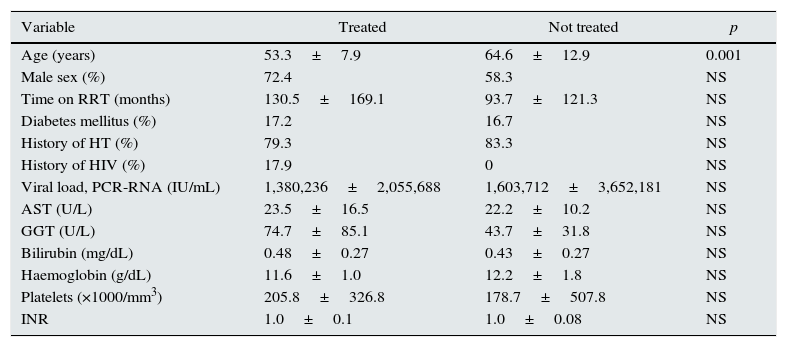

ResultsHCV antibodies were analysed in 465 haemodialysis patients from two hospital areas, and 54 (11.6%) were found to be positive. Among these, 29 (53.7%) were treated with different DAA regimens. Table 1 shows the characteristics of the treated and untreated patients. Only the difference in age was significant between groups. In the untreated patient group, reasons for non-treatment included high comorbidity with a short life expectancy in 5 cases, age over 80 years in 4 cases, clinical stability with no changes in laboratory tests or abnormalities on the FibroScan in 5 cases, having genotype 3 in 2 cases, and due to an undetectable viral load in 9 patients (6 spontaneously and 3 due to previous treatment with interferon and ribavirin).

Baseline characteristics of HCV-positive patients treated and not treated with direct-acting antivirals.

| Variable | Treated | Not treated | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 53.3±7.9 | 64.6±12.9 | 0.001 |

| Male sex (%) | 72.4 | 58.3 | NS |

| Time on RRT (months) | 130.5±169.1 | 93.7±121.3 | NS |

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 17.2 | 16.7 | NS |

| History of HT (%) | 79.3 | 83.3 | NS |

| History of HIV (%) | 17.9 | 0 | NS |

| Viral load, PCR-RNA (IU/mL) | 1,380,236±2,055,688 | 1,603,712±3,652,181 | NS |

| AST (U/L) | 23.5±16.5 | 22.2±10.2 | NS |

| GGT (U/L) | 74.7±85.1 | 43.7±31.8 | NS |

| Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.48±0.27 | 0.43±0.27 | NS |

| Haemoglobin (g/dL) | 11.6±1.0 | 12.2±1.8 | NS |

| Platelets (×1000/mm3) | 205.8±326.8 | 178.7±507.8 | NS |

| INR | 1.0±0.1 | 1.0±0.08 | NS |

AST: aspartate aminotransferase; GGT: gamma-glutamyl transferase; HT: hypertension; RRT: renal replacement therapy; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus infection.

Among the patients treated with DAAs, the most common aetiology was glomerular in 11 cases (37.9%), followed by diabetic nephropathy in 4 (13.8%), vascular in 3 (10.3%), interstitial nephropathy in 2 (6.9%), unknown in 2 (6.9%), 1 case of polycystic disease (3.4%) and other causes in 6 patients (20.6%). The genotypes that presented were 1b in 18 cases (62.0%), 1a in 8 cases (27.5%) and genotype 4 in 3 patients (10.4%).

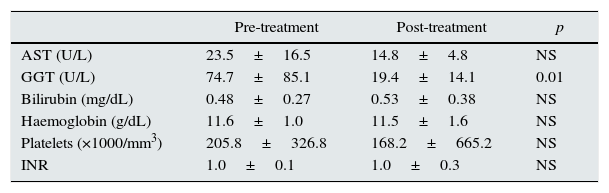

The viral load of patients before DAA treatment was 1,283,288±2,165,432IU/mL. After treatment, regardless of the regimen prescribed, all patients had a negative viral load and SVR at 24 weeks. Table 2 shows the changes in laboratory values before and after treatment, where a significant decrease in GGT levels alone can be seen.

Laboratory values before and after treatment.

| Pre-treatment | Post-treatment | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| AST (U/L) | 23.5±16.5 | 14.8±4.8 | NS |

| GGT (U/L) | 74.7±85.1 | 19.4±14.1 | 0.01 |

| Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.48±0.27 | 0.53±0.38 | NS |

| Haemoglobin (g/dL) | 11.6±1.0 | 11.5±1.6 | NS |

| Platelets (×1000/mm3) | 205.8±326.8 | 168.2±665.2 | NS |

| INR | 1.0±0.1 | 1.0±0.3 | NS |

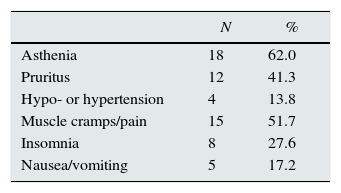

Table 3 shows treatment-related adverse effects. Asthenia and muscle cramps/pain were the most common. There were no differences between the different regimens. Serum haemoglobin levels did not change significantly (Table 2), but it should be taken into account that the doses of erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESA) were increased, although the changes did not reach statistical significance (4894±4689 vs. 7789±6721IU/week). Transfusion of packed red blood cells or discontinuation of treatment due to adverse effects was not necessary in any case.

In patients treated with ribavirin, serum haemoglobin levels dropped an average of 0.3±1.9g/dL, despite having increased the mean dose of ESAs (5300±6864IU/week), while in those who had not received ribavirin, the ESA dose was increased by a smaller amount (1750±3412IU/week), with a slight increase in haemoglobin levels (0.16±1.3g/dL).

DiscussionOur study shows that treatment of HCV-positive haemodialysis patients with different DAA regimens is safe and effective: an SVR was obtained in all cases, with few adverse effects. Very few studies have been published to date on the treatment of haemodialysis patients, and the vast majority correspond to series with small patient numbers; our findings are consistent with the series described.17–21 Recent studies show that the response of haemodialysis patients to DAAs is better than that obtained in patients with no renal disease.22 Our results confirm the need to treat all haemodialysis patients with this infection, provided there are no contraindications. This recommendation is particularly important in patients on the renal transplant waiting list, since HCV infection is accompanied by an increased risk of rejection, proteinuria, infections and the development of diabetes, HCV-associated glomerulopathy and post-transplant liver complications.23,24

In our series, the prevalence of HCV infection was 11.6%, somewhat higher than that reported in the DOPPS V study for Spain in 2015, which was 8.9%4; it may be that nosocomial transmission is decreasing as a result of isolation measures and the decrease in the number of transfusions.25

The AASLD and Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA),26 in their guidelines dated 24/02/2016, recommend daily treatment with elbasvir (50mg) and grazoprevir (100mg) for 12 weeks in patients with advanced CKD or on dialysis with genotypes 1a, 1b or 4, based on the findings of the recently published C-SURFER study.16 However, none of these drugs are yet to be approved in Spain. Of the drugs available in Spain, for our haemodialysis population, in patients with genotype 1b, treatment with the paritaprevir (150mg)/ritonavir (100mg) and ombitasvir (25mg) combination is recommended in a single daily dose, together with dasabuvir (250mg) twice daily for 12 weeks; in cases of infection with genotype 1a, which is more resistant to DAAs than genotype 1b, adjusted doses of ribavirin should be added (200mg/3 times per week or even daily). Treatment should be discontinued if haemoglobin levels fall by more than 2g/dL despite the use of ESAs.19 In patients infected with genotypes 2, 3, 5 or 6, pegylated interferon and adjusted doses of ribavirin (200mg/day) are recommended.26

There is no agreement in regard with the best DAA regimen for treating HCV infection in haemodialysis patients. Numerous combinations have been described, which appear to be related with the antivirals approved in the different countries involved. Evidence suggests that simeprevir, ledipasvir, paritaprevir/ritonavir, ombitasvir, dasabuvir, asunaprevir and daclatasvir are safe in patients on dialysis.22 In our case, the most commonly used regimen was the combination of paritaprevir/ritonavir, ombitasvir and dasabuvir, although other regimens with different combinations of DAAs, including sofosbuvir, simeprevir, ledipasvir and daclatasvir, were used to a lesser extent. In any case, an SVR was the norm in all cases, regardless of the DAA combination received.

Sofosbuvir is the first pan-genotypic DAA, but is not recommended in advanced CKD (estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR] less than 30mL/min) due to the risk of deterioration in renal function.17,20,27 This adverse effect is irrelevant in haemodialysis patients, since patients are anuric in most cases. Nevertheless, experience with this drug in these cases is scant, and its safety is pending confirmation. Two of our patients were treated with sofosbuvir in combination with ledipasvir or simeprevir, presenting outcomes equivalent to the more commonly used regimens as well as a good tolerance. These findings corroborate those reported by other authors in short patient series,18,28,29 but larger studies are needed so that conclusions may be drawn. Other DAA combinations pending incorporation in the therapeutic arsenal, such as grazoprevir/elbasvir and daclatasvir/asunaprevir/beclavubir, could open new options for these types of patients.16

Among the different HCV genotypes, subtypes 1a and 1b are the most common in the general population and in our dialysis population, followed by genotypes 3, 2 and 4. The treatment response with the different DAA regimens used was SVR in almost 100% of cases, both in patients with and without cirrhosis. In contrast, for genotypes 2, 3, 5 and 6, the recommendation continues to be the traditional treatment with interferon and ribavirin at adjusted doses.26 However, given the poor tolerance to interferon in haemodialysis patients, which is even worse when combined with ribavirin,10,30,31 the few cases in our series with these genotypes still remain untreated, awaiting the approval of new DAAs.

Ribavirin was used in some of our patients with a dose adjustment. It was generally well tolerated, although the decrease in haemoglobin levels was more marked than in patients who were not treated with this drug, as described in other series.32 In principle, it seems reasonable to allow this agent to be combined with the other DAAs in more severe cases, those with HIV coinfection, genotype 1a and in cases of cirrhosis.26 Moreover, given the frequent tendency towards anaemia,32,33 it seems reasonable to increase the ESA dose as a preventive measure, before haemoglobin levels fall, as a way to avoid potential transfusions and the need to discontinue the drug.

All the patients treated presented an SVR at the end of 24 weeks. While one might think that this will be maintained over a long time, it would be advisable to determine the viral load every 3–4 months to begin with and annually thereafter until more experience with long-term outcomes is available.

Due to the risk of nosocomial transmission of HCV in haemodialysis units,34 many HCV-positive patients are being dialysed in separate units or with shifts or monitor isolation. The outcomes obtained with the DAAs suggest that these measures need to be reconsidered. It seems reasonable to suggest, based on our experience, that patients with anti-HCV antibodies and an SVR should continue to be dialysed in the general unit along patients who are anti-HCV antibody-negative, given that the risks of leaving them with other untreated patients and patients with other genotypes may be greater and complicate their prognosis. As more and more HCV-positive patients are treated, isolation rooms for patients with HCV may tend to disappear. In any case, the development of an effective vaccine against HCV should be the ultimate goal.35–37

One of the major limitations of DAA treatment is the cost. Data from the Spanish Ministry of Finance and Public Administration show that the net annual accrued expenditure related with these types of hospital treatments for 2015 increased by 25.8% in Spain.38 However, the cost–benefit in the longer term must be evaluated, taking into account admissions, ascitic decompensations, complementary treatments and the potential effect on the development of cirrhosis and mortality. Furthermore, presumably during this time, we have experienced a peak stage with the mass treatment of patients, which is expected to be followed by a trough, due to a decrease in the number of patients. As such, costs, logically, should fall.

Our study presents some limitations, such as the small number of patients included, the short follow-up and a lack of uniformity in the treatment regimens, but it has the strengths of being the first series of haemodialysis patients treated with DAAs in Spain, and allowing us to conclude that the outcome obtained within the follow-up time is excellent.

In summary, we can conclude that the use of new DAAs in the treatment of HCV in haemodialysis patients provides great efficacy, with minimal side effects, and constitutes a major advance in the treatment of these patients.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest regarding the content of this manuscript.

Please cite this article as: Abad S, Vega A, Rincón D, Hernández E, Mérida E, Macías N, et al. Eficacia de los antivirales de acción directa en la infección por el virus de la hepatitis C en pacientes en hemodiálisis. Nefrologia. 2017;37:158–163.