To the Editor,

Spontaneous ruptures of kidney grafts are an uncommon but potentially severe complication of kidney transplants nowadays. They can lead to the loss of the graft or even to death.1 Prior to calcineurin inhibitors, this complication was quite common, and it was mainly caused by acute rejection (AR). After the introduction of cyclosporine, the most common aetiologies are renal vein thrombosis2 and acute tubular necrosis (ATN).3,4 Cases associated with trauma to the graft have also been described.5 Most cases of graft rupture occur in the first 3 weeks after the transplant.6 It rarely occurs later. The most frequent symptoms are the triad of pain over the graft, oliguria and hypotension7 and the diagnosis can be confirmed with ultrasound and CT scans.8 In the past, an emergency nephrectomy was the most common treatment in unstable patients, but more recently it has been possible to save up to 80% of the grafts9 using aggressive haemodynamic stabilization and emergency surgical repair.10

We present the case of a 50 year old male kidney transplant recipient of 9 months of evolution who went to hospital after suffering anuria for 12 hours and back pain on the same side as the graft. Of note in his medical history was CKD, probably secondary to nephroangiosclerosis, treated with peritoneal dialysis for 2 years before the transplant, secondary hyperparathyroidism under treatment with cinacalcet, controlled chronic AHT, dyslipemia, and a tobacco habit prior to the transplant. He received his first kidney transplant in May 2007 from a 55 year old cadaveric donor, receiving immunosuppressor treatment with 2 doses of basiliximab, tacrolimus, mycophenolate sodium, and steroids. Renal function began immediately, and he progressed well and reached a basal creatinine level of around 1.5 mg/dl a month after the transplant. He underwent periodic check-ups as an outpatient, complying with his medication regime. A week before admission he had attended his programmed 9-month check-up, presenting with stable kidney function (creatinine 1.5 mg/dl, MDRD 60 ml/min, and haemoglobin 15.8 g/dl), with no signs of proteinuria or haematuria, and blood pressure of 136/80 mm Hg. An ultrasound scan 2 months before admission showed a renal graft of 122 mm in length, with normal echostructure and morphology with no evidence of collections, RF 0.62-0.64.

On the day of admission the patient presented with anuria, a mild fever of 37.5 ºC, no apparent signs of infection, blood pressure of 148/89 mm Hg, heart rate of 76 bpm. He was suffering left lumbar pain, and moderate pain in the left iliac fossa above the graft on palpation, with no other significant findings. Blood test: haemoglobin 13.6 g/dl, hematocrit 39.7%, total leukocytes 14,500/µl, neutrophils 85%, creatinine 7.7 mg/dl, urea 145 mg/dl, sodium 139 mEq/l, potassium 4.7 mEq/l, pH 7.34, sodium bicarbonate 21.2 mmol/l, INR 1,1, thromboplastin time 31 s. Urine analysis: 375 erythrocytes/µl and proteins 1000 mg/dl. Blood levels of tacrolimus: 8.5 ng/ml). The patient reported no trauma to the graft and had not undertaken strenuous physical activity. There were no changes in his medication and the patient assured his compliance with the treatment. Treatment until the day of admission included: prednisone 5 mg/24 h, mycophenolate sodium 720 mg/12 h, tacrolimus 1 mg/12 h, omprazole, atorvastatin, amlodipine, irbesartan and sodium bicarbonate.

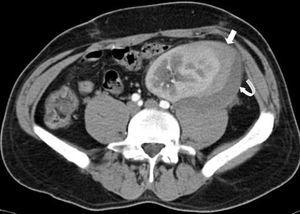

An emergency Doppler echocardiogram was performed showing the graft of 121 mm in the left iliac fossa (LIF) with increased cortical echogenicity, good perfusion, RF: 1. An organized perirenal haematoma of 93 x 37 x 60 mm was identified. To complete the study, a CT scan with contrast was performed showing enhancement of all the kidney with 2 hypoechoic linear lesions. These were interpreted as a fracture of the anterior pole of the graft (Figures 1 and 2). No aneurysm or kidney tumours were observed. In view of the patient being haemodynamically stable and the diagnosis of advanced kidney rupture, emergency surgery was ruled out. An initial session of haemodialysis was performed; diuresis began again after 48 h with progressive improvements in the analytical parameters. The diagnosis of AR was ruled out given the patient’s good progress without having taken other therapeutic measures and the fact that his immunosuppressor levels were within the normal range.

On the eighth day, after having no new complications, he was discharged with a serum creatinine level of 2.6 mg/dl. He then showed gradually improving renal function until reaching a serum creatinine level on day 14 close to the baseline level (1.7 mg/dl). Since then (2 years) his renal function has remained stable with no proteinuria or haematuria.

During this time we have not managed to characterise the aetiology of the episode, having ruled out the most common causes of graft ruptures such as AR,11 renal vein thrombosis,2 or trauma to the graft.5 Subsequent ultrasound scans and 2 CT scans, 6 and 12 months after admission, showed no signs of ectasia, perirenal collections, angiomyolipoma, or tumours. We believe that the situation of anuria and acute kidney failure could be justified by the presence of acute tubular necrosis secondary to compression on the parenchyma by the haematoma. This was probably present on the days prior to admission. This case is of interest in that it involves a delayed spontaneous rupture of the graft in a patient with a stable kidney transplant with an evolution of 9 months which can not be attributed to the most common causes.

Figure 1. CT scan of the graft showing a perirenal collection of the graft compatible with fracture of the inferior pole (thin arrow)

Figure 2. CT scan of the graft showing hypoechoic linear lesions compatible with fracture of the anterior pole (thin arrows)