Content

Dabigatran has been shown to be more effective than heparin in total hip replacement thromboembolic prophylaxis and to have similar efficacy with less risk of bleeding in the treatment of deep venous thrombosis.2 The RE-LY3 study showed its greater efficacy in the prevention of ictus than warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. However, in the subgroup study, patients who were 75 years of age or older had a higher risk of extracranial bleeding, probably in relation to high concentrations of the drug.4 With a peak plasma concentration 2 hours5,6 after intake and a half-life of 12-17 hours,5,6 it has a renal clearance of 80%.5,6 It is recommended to reduce the dose for patients with an estimated glomerular filtration rate between 30 and 50ml/min/1.73m2. If the GFR falls below 30ml/min/1.73m2, the drug is contraindicated.7

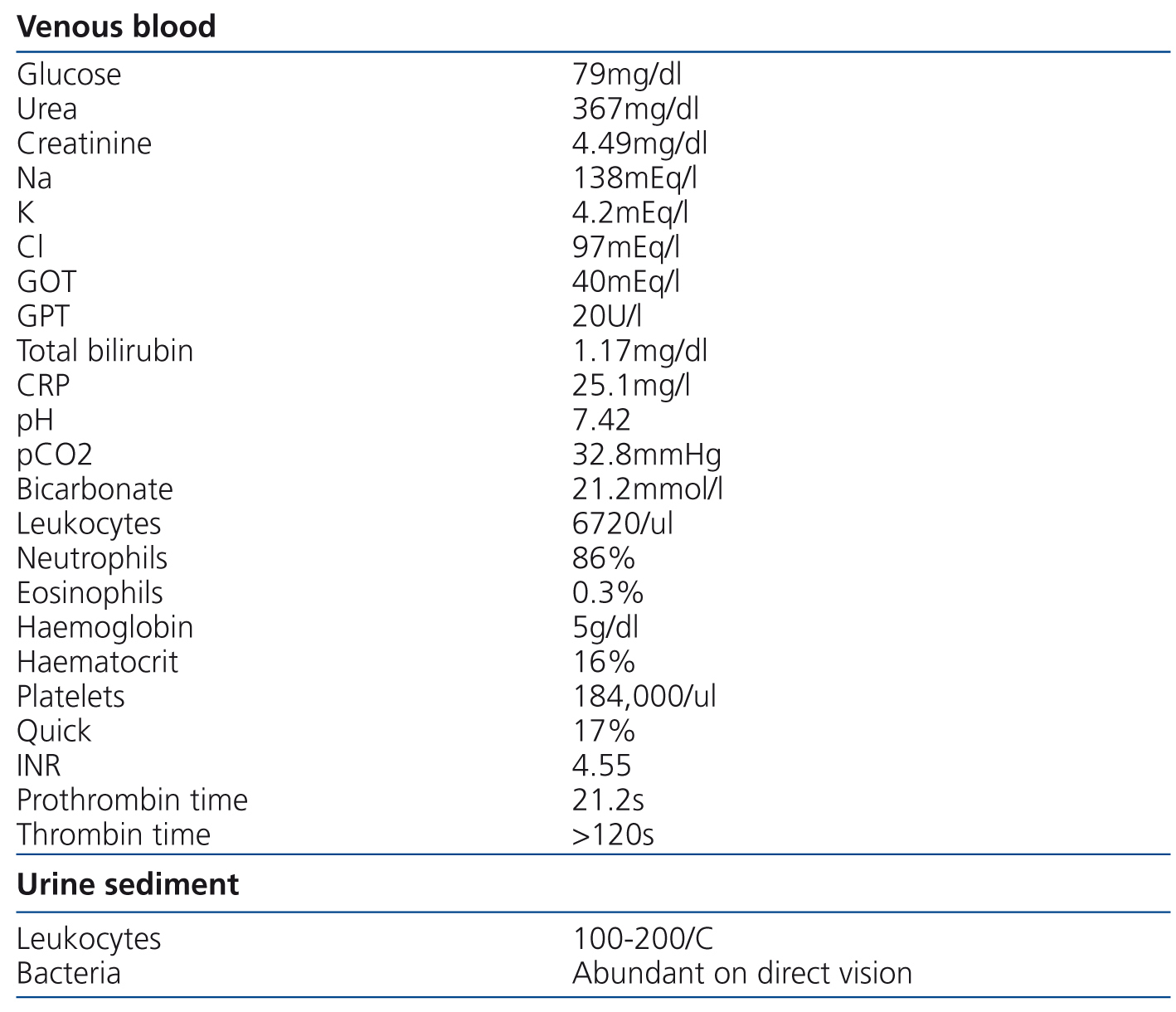

We present the case of an 84-year-old female with high blood pressure, type 2 diabetes mellitus, atrial fibrillation, hypertensive heart disease with preserved systolic function, stage 3 chronic kidney disease with an estimated glomerular filtration rate of 30ml/min/1.73m2 and normocytic normochromic anaemia, who presented with progressive general deterioration in recent months, without abnormalities in the characteristics of urine or the diuresis rate. She was being treated with several antihypertensive drugs (including angiotensin II receptor antagonists and beta-blockers), a statin and fibrate combination and dabigatran (75mg every 12 hours). Her general appearance was poor. The cardiac examination was normal, but auscultation revealed crackles in both lung bases. No abdominal abnormalities or increases in dependent oedema were found. The digital rectal examination was negative for melena and rectal bleeding. Blood pressure was 94/36mmHg. The electrocardiogram showed sinus rhythm of 54 beats per minute with V4-V6 straight ST segment not suggestive of acute myocardial ischaemia. The test results are displayed in Table 1. The x-ray showed cardiomegaly, bilateral posterior pleural effusion and vascular redistribution. There were no significant abnormalities in the abdominal x-ray. Due to the low blood haemoglobin concentration (5g/dl), she received an initial transfusion of three packed red blood cell units and antibiotic treatment with ceftriaxone and ciprofloxacin was started due to findings consistent with urinary tract infection and she was admitted to the Nephrology Department for studies. Due to the suspicion of upper intestinal bleeding, we decided to perform haemodialysis to clear dabigatran. Hours later, she produced melenic stools. A gastroscopy was performed, showing friable erythematous mucosa and a small clot in the angular notch. We performed another haemodialysis session twelve hours later. Clotting times gradually normalised over the following days and the patient did not display more bleeding.

Our case is an example of the potential disadvantages of administering dabigatran to patients with chronic kidney disease, since they have a higher risk of acute renal failure8 and a critical increase in levels of the drug in serum. The patient received a dose adjusted to the glomerular filtration rate and displayed excessive anticoagulation due to exacerbation of her condition. Moreover, although it is often said that it does not require monitoring, there is no parameter that adequately assesses the anticoagulant activity of this new drug. Although the use of activated partial thromboplastin time or thrombin time have been established, these may underestimate the anticoagulant activity and are only useful for their negative predictive power. Prothrombin time is not useful either because it may be normal despite high serum dabigatran concentrations. The parameter that displays the best relationship with the level of dabigatran in serum is ecarin clotting time, which is not very useful because it requires a number of days for results to be obtained and it is not easy to perform. Despite the use of recombinant activated factor VIIa for patients with bleeding due to dabigatran, the only useful strategy for overdose management is clearing the drug via haemodialysis, taking advantage of its low molecular weight (471Da) and its low plasma protein binding rate (35%).9 It should be taken into account that there is a rebound phenomenon for dabigatran concentration in plasma after the procedure, given its high distribution volume.9 It is important to be aware that there are patients whose clinical condition is liable to change in a short period of time and that they will require regular check-ups. In these patients, such as those affected by chronic kidney disease, who are prone to erratic changes in drug concentrations, we should rationally consider the benefit/risk balance of using dabigatran.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest related to the contents of this article.

Table 1. Data of test on admission