La peritonitis es una de las complicaciones más graves de la diálisis peritoneal. Las bacterias son las responsables de la mayoría de los casos. La infección fúngica es infrecuente, pero se asocia con una alta morbilidad, con la imposibilidad de continuar en el programa de diálisis y con un importante índice de mortalidad. Su incidencia varía del 1% al 10% de los episodios de peritonitis en niños y del 1% al 23% en adultos. Su presentación clínica es similar a la de la peritonitis bacteriana. Los factores predisponentes de peritonitis fúngica no han sido establecidos con claridad; los episodios previos de peritonitis bacteriana y el tratamiento con antibióticos de amplio espectro han sido descritos a menudo en la literatura. Las especies de Candida son los patógenos más habituales y Candida albicans la más frecuente, pero en la última década se ha observado una alta prevalencia de Candida parapsilosis. El diagnóstico microbiológico es fundamental para determinar la etiología y prescribir el tratamiento, que suele requerir, además de la terapia antifúngica, la retirada del catéter peritoneal y la consecuente transferencia a hemodiálisis. Fluconazol y anfotericina B son los antifúngicos recomendados; los nuevos fármacos como voriconazol y caspofungina han demostrado tener también una gran utilidad. El propósito de esta revisión sistemática ha sido analizar los aspectos clínicos y microbiológicos de la peritonitis fúngica, los cuales son poco conocidos y han cambiado en los últimos años.

INTRODUCTION

Peritonitis is one of the most serious and frequent complications in patients undergoing kidney replacement therapy with peritoneal dialysis, especially in continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. Patients treated with peritoneal dialysis are exposed to infections due to unnatural communication with the exterior through the peritoneal catheter and the repeated introduction of more or less biocompatible solutions into the peritoneal cavity. Repeated peritonitis episodes may lead to irreversible damage to the peritoneal membrane, which may require suspending the technique and transferring the patient to haemodialysis.

Bacterial infection is responsible for approximately 80% of peritonitis episodes associated with peritoneal dialysis. Fungal infection is an uncommon complication which mostly occurs in patients who have been undergoing dialysis for an extended period of time; it does not normally arise as a first episode. The exceptional nature of fungal peritonitis has made it difficult to establish general action criteria, since the low number of episodes that authors usually describe in their series does not permit us to extrapolate results.

In this study, we will use a systematic review to analyse articles on fungal peritonitis that have been published in the literature. The objective is to extract conclusions that will provide us with a better understanding of this clinical condition.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

The clinical research articles that we reviewed were selected among those published in the last three decades. They include original studies, reviews, clinical cases and letters to the editor regarding fungal peritonitis in patients undergoing peritoneal dialysis treatment. We used two sources for the bibliographical search: firstly, the Ovid Technologies platform which contains nearly all of the existing databases (Medline, Embase, Current Contents, Cinahl, Inspec, Psycinfo, etc.) and enables us to consult a large number of full-text articles, and secondly, the PubMed search engine developed by the National Center for Biotechnology Information, which provides access to the bibliographic databases compiled by the National Library of Medicine. In addition, we consulted other habitual sources: EBSCO Open Journals, Proquest Medical Library, Science Direct, Springer Links and Wiley Interscience.

We used the following search terms: fungal peritonitis, peritoneal dialysis, continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis, Candida, Cryptococcus, Geotrichum, Saccharomyces, Malassezia, Pichia, Rhodotorula, Trichosporon, Blastomyces, Coccidioides, Paracoccidioides, Histoplasma, Acremonium, Alternaria, Aspergillus, Aureobasidium, Beauveria, Bipolaris, Chaetomium, Chrysonilia, Chrysosporum, Cladophialophora, Cladosporium, Curvularia, Drechslera, Emmonsia, Exophiala, Fonsecaea, Fusarium, Natrassia, Onychocola, Paecilomyces, Penicillium, Phialemonium, Phialophora, Rhamichloridium, Rhinocladiella, Scedosporium, Scopulariopsis, Scytalidium, Sporothrix, Trichoderma, Absidia, Cunninghamella, Mucor, Rhizomucor, Rhizopus, Syncephalastrum.

Based on the resulting bibliography, we gathered information on the epidemiology and pathogeny of the fungal peritonitis, the risk factors for its development, the distribution of aetiological agents (both yeasts and filament fungus) responsible for peritonitis episodes, the clinical manifestations, the microbiology diagnostic techniques and the therapeutic options.

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND RISK FACTORS

Fungal peritonitis in peritoneal dialysis is an infrequent complication. Its incidence rate is similar in automated peritoneal dialysis and continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis, although with the automated technique, the lower number of connections can reduce the episodes. Fungi penetrate the peritoneal cavity through intraluminal or periluminal pathways and cross the intestinal mucosa, or enter through the haematogenic pathway due to a distant fungal infection.

Although fungal infection makes up about 4-10% of the peritonitis cases in children and 1-23% of those in adults according to the series,1-18 resulting in an average of 4-6% of all peritonitis episodes, it has a worse prognosis than a bacterial infection does. This is because a fungal infection favours catheter obstruction, abscess formation and the development of peritonitis.3,4,7,8,10,19-23 A mortality rate of 5-53% has been reported for patients with this condition and a technique failure rate of 40-55%, which forces us to discontinue peritoneal dialysis and transfer patients to haemodialysis.1,4,9,10,12,13,19,23-27

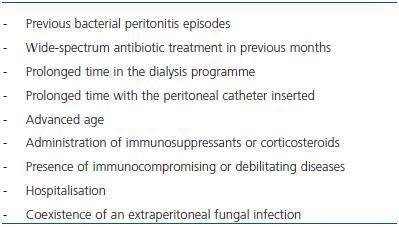

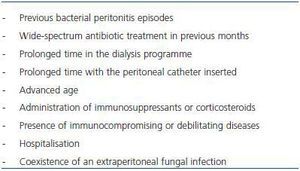

Risk factors for developing fungal peritonitis have not been clearly determined. Numerous situations have been listed which play an important role in the appearance of the mycotic infection, including previous episodes of bacterial peritonitis and wide-spectrum antibiotic treatment. Often, more than one risk factor is identified in patients. Table 1 shows the most frequently described risk factors.

Patients with fungal peritonitis present a higher rate of bacterial peritonitis episodes than patients without FP,2,5,10,11,13,14,20,23,28-31 sometimes more than two times higher,8,14,23 owing to the fact that the peritoneal inflammation can increase susceptibility to a fungal invasion. It has been suggested that fungal infection appears most of all after episodes of bacterial peritonitis due to gram-negative bacilli.16,27 The administration of wide-spectrum antibiotics in previous months, generally as a treatment for bacterial peritonitis episodes, is closely related to the appearance of fungal peritonitis, and is indicated in 30-95% of the episodes described in the literature,1-4,7-11,13-16,18,23,25,26,29,30 although the absence of prior antimicrobial therapy does not exclude the possibility of infection.15 In cases of peritonitis due to environmental fungus filaments, it seems that the use of antibiotics does not play such an important role.13

Other listed risk factors are prolonged time in the peritoneal dialysis programme and the time elapsed from insertion of the peritoneal catheter.3-5,8,12,30 Maintaining the catheter after detecting the fungal infection is related to a worse prognosis, and on some occasions has been the main factor causing failure of the technique and mortality.8,12,13,15,18,25,26

Advanced age has been cited on various occasions as a noteworthy trait in patients with fungal peritonitis.6,8,14,26,30,31 Similarly, the administration of immunosuppressants such as corticoids1,15 and the presence of immunocompromising or debilitating diseases, such as systemic lupus erythematosus27,32 or HIV33 are cited as risk factors. Diabetes mellitus in particular is identified as a risk factor in 30-65% of all episodes,7,13-15,19,23,25,26,31 although it is also frequently present with bacterial peritonitis. Hospitalisation is considered to be a risk factor when an infection of nosocomial origin occurs, as is the coexistence of an extraperitoneal fungal infection that causes a peritoneal infection through a haematogenic pathway.14,29

On the other hand, no significant differences are observed with respect to sex, as some authors cite higher incidence rates in females31,34 and others in males.26 Neither the renal failure aetiology (due to a vascular cause, glomerulonephritis, diabetic nephropathy, tubulointerstitial nephropathy, renal polycystosis, others), the cardiovascular comorbidity (arrhythmias, ischaemic heart disease, cerebral vascular disease, peripheral vascular disease) nor the season of the year8,35 have been linked to the condition.

AETIOLOGICAL AGENTS

Infectious peritonitis in patients who undergo peritoneal dialysis is commonly caused by bacteria. The most common agents are coagulase-negative Staphylococcus and Staphylococcus aureus, followed by Streptococcus, Enterococcus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae; other bacteria are occasionally involved. In some cases, aetiology is mixed (bacterial and fungal) or polymicrobial.13,36-38 The aetiology of fungal peritonitis, however, is very diverse and includes most yeast species and human pathogenic fungal filaments, as well as other environmental yeasts and fungi that are uncommon in clinical practice.

YEASTS

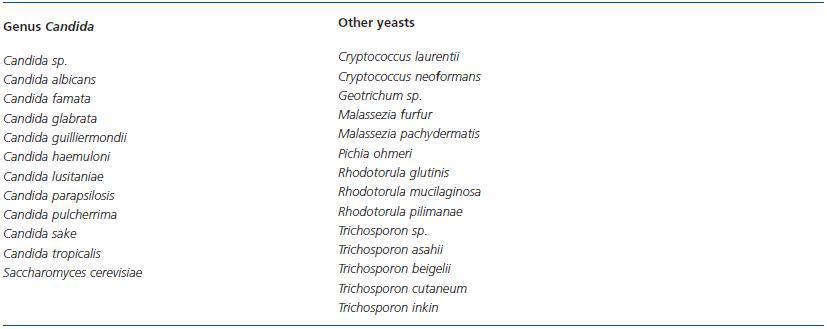

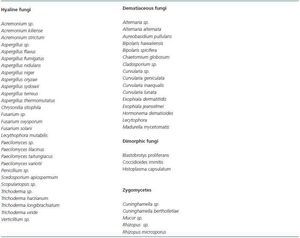

Yeasts are widely distributed in nature, as these organisms are capable of living in extraordinary environmental conditions. Of the approximately 500 known species, only about 25 or 30 were considered pathogens a few years ago, but recently their number has grown considerably. Table 2 lists the yeasts that are implicated in peritonitis episodes in patients undergoing peritoneal dialysis.

Strains of the genus Candida have the highest incidence rate in fungal peritonitis in peritoneal dialysis, and are responsible for about 60-90% of all cases.1,4,15,19,20,23,30,31,34 Candida albicans has classically been considered the predominant species. In recent years, C. parapsilosis, which habitually colonises the skin and has a proven ability to adhere to synthetic materials, has at times been implicated as much or more than C. albicans1,4,15,19,20,23,30,31,34 and its presence is associated with a poorer prognosis and the need for a more aggressive treatment.4,20,39 Currently, we can state that C. parapsilosis is the most common pathogen in fungal peritonitis in patients undergoing peritoneal dialysis.

The incidence rates for other Candida species are not wellestablished because the species is not identified in many cases and only listed as Candida sp. Over the last decade, the number of non-albicans species has been growing and their involvement has become associated with increased mortality, given that some are resistant to the usual antifungals used in treatment.1,2,4-6,8,9,13,15,19,21,23,28,30,31,34,40-49

The literature did not reveal any cases of infection with C. krusei, which has a natural resistance to fluconazole.

Other peritonitis-causing yeasts are exceptional and have only been cited in a few episodes. There are some published cases of peritoneal infection as a manifestation of systemic infection with Cryptococcus neoformans43,50,51 and another case due to C. laurentii.52 The Trichosporon genus is a more constant peritoneal pathogen, whether we refer to the 56-58 species T. beigelii,31,53-55 the only one that was recognised a few years ago, or some of the new species (T. inkin, cutaneum,30,59 T. asahii30,60). While the Rhodotorula genus rarely causes infections in humans, there have been cases of peritonitis due to R. mucilaginosa (previously known as rubra),15,16,30,61-63 R. glutinis64 and R. pilimanae.6 We have also found isolated cases of peritoneal infection due to Pichia ohmeri65 and Geotrichum sp.,66 as well as Malassezia furfur,67 a lipophilic yeast that causes pityriasis versicolor, and Malassezia pachydermatis,68 an inhabitant of the external ear canal in canids.

Some dimorphic fungi, with yeast-like and filament morphology, have occasionally been described in peritonitis with peritoneal dialysis: Histoplasma capsulatum69,70 and Coccidioides immitis,71 both of which are pathogens, and Blastobrotys proliferans,72 which is never mentioned in human infections.

FILAMENTOUS FUNGI

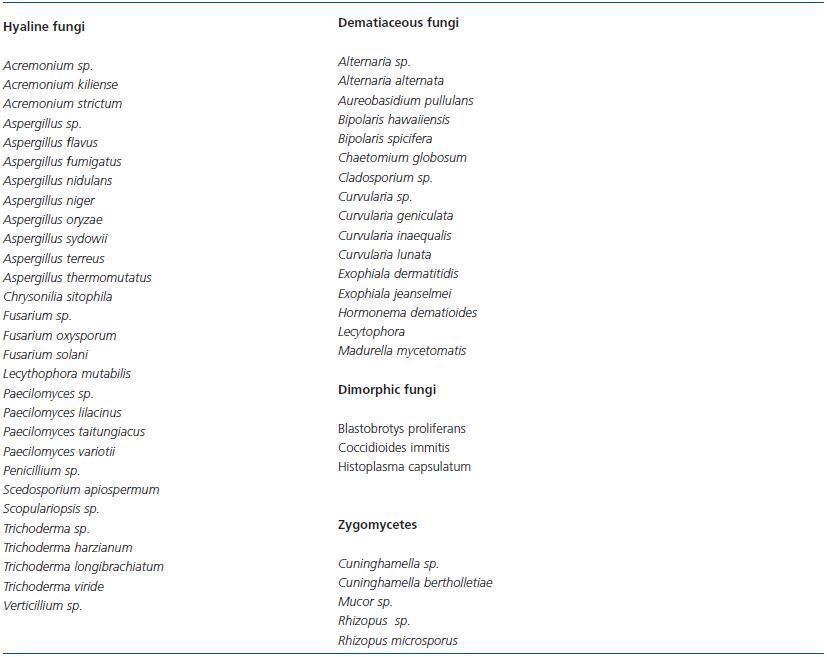

Filamentous fungi or moulds, like yeasts, are widely found in nature. They are described in peritonitis at a much lower percentage than yeasts are, but their involvement is growing, and in some series makes up 40% of cases.26 The fact that these fungi are more resistant to antifungals has sparked special clinical interest. The listed genera and species are quite varied and include hyaline, dematiaceous and zygomycete fungi; some are related to human infections and other saprophytes have only rarely been described in clinical studies. Table 3 lists the filamentous fungi that have been involved in fungal peritonitis with peritoneal dialysis.

Despite the fact that the Aspergillus genus is one of the most frequent in clinical practices, cases of peritoneal infection are not very numerous.6,13,22,,26,34,35,64,73-83 Penicillium is referred to on several occasions, but without listing the species.26,38,84-87

Episodes of peritonitis due to Paecilomyces are detected quite rarely.6,88-94 The genera Acremonium and Fusarium are also of special interest due to their resistance to antifungals.6,23,26,34,90,95-102 The so-called black yeasts of the Exophiala genus have also been implicated in peritoneal infection cases94,103-107 as well as the Curvularia genus which rarely causes disease in humans.53,108-111

Other filamentous fungi are less common in peritonitis cases in patients undergoing peritoneal dialysis. Some are known as opportunistic pathogens: Alternaria,112,113 Bipolaris,114,115 Aureobasidium pullulans,116,117 Scedosporium apiospermum,118 Scopulariopsis sp.,119 Cladosporium sp.26 and Madurella mycetomatis.30 Others are less commonly reported as pathogens: Trichoderma,90,120-122 Chaetomium globosum,123 Chrysonilia sitophila,123 Lecythophora mutabilis,124 Hormonema dematioides,125 and Verticillium sp.126

Zygomycetes are fungi that are uncommon as peritonitis agents in patients undergoing peritoneal dialysis, but they are associated with a high mortality rate due to their lack of response to antifungals.78 Cases of peritonitis due to Rhizopus sp.16,127,128,78,129,130 and Cuninghamella26,131 have been reported.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

From a clinical viewpoint, fungal peritonitis is indistinguishable from bacterial peritonitis; both present symptoms of abdominal pain, and less frequently, fever, nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, worsened general state and cloudy peritoneal effluent. The diagnosis is carried out by a biochemical analysis of the peritoneal liquid when a count of 100 leukocytes or higher per microlitre is detected where at least 50% are polymorphonuclear, but microbiological analysis is necessary in order to establish the fungal etiology.15 We must be mindful that the liquid can sometimes offer a low count if it has been in the peritoneal cavity for less than two hours; a predominance of polymorphonuclear cells can indicate infection in these cases. As fungemia is rarely present, there is usually no systemic leukocytosis.

We can suspect an episode of fungal peritonitis when there are recurring episodes of bacterial peritonitis and a lack of response to antibiotic treatment. Among the analytic data associated with fungal infection, only the following have been described as significant: the presence of anaemia and a plasma albumin drop below 3g/dl, and occasionally, eosinophilia in the dialysate.8,14,52,71,75,77 Hypoalbuminaemia can be explained by the lack of ultrafiltration that takes place during the peritonitis episode, or by the increase in peritoneal loss of proteins. This factor has been linked to a poorer prognosis,18 although the prognostic factors for fungal peritonitis are not clearly defined. Maintaining the peritoneal catheter and the presence of ileus and abdominal pain seem to imply increased mortality.4,7

MICROBIOLOGICAL DIAGNOSIS

The microbiological diagnosis is based on microscope viewing or on isolating fungal cultures from the peritoneal dialysate. In general, particularly in the case of environmental fungi, we must demonstrate their presence in more than one sample to be able to confirm their participation as an agent causing peritonitis; these fungi are contaminants that are frequently isolated in cultures.131

The laboratory should receive 50-100ml of peritoneal fluid, of which 10ml are inoculated in aerobic and anaerobic blood culture bottles and left to incubate over seven days at 35-37º C. The rest is centrifuged at 3000rpm during 15 minutes. Using the sediment, we then proceed to direct microscopic viewing of both fresh and the stained samples. At the same time, we inoculate the sample in general and specific culture media to examine for bacteria and fungi. In a clear case of suspected fungal peritonitis, the culture medium CHROMagar Candida can be added, which is extremely useful for differentiating yeasts.34

The direct microscopic observation and the Gram stain have highly variable sensitivities between 10 and 70% according to different authors, but they are higher than those for bacterial peritonitis.6,13,26 Despite their dubious results, they are effective in the early detection of fungal elements, which makes it possible to consider removing the peritoneal catheter and establish a specific treatment.13,25 The microbiological culture has a sensitivity of nearly 100% and allows us to identify the species of the infection-causing agent. Yeasts are identified by their morphological, biochemical and nutritional characteristics, fundamentally by the their pattern of carbon compound assimilation, for which we use commercial systems such as ID 32C (bioMérieux, France) and others.13 Filamentous fungi, however, are identified exclusively by their growth time, the morphological characteristics of the colony (size, colour, texture, borders, diffusible pigment) and their microscopic characteristics (hyphae, phialides, conidiophores, conidia). Currently, serological diagnostic techniques are available to us, such as the detection of the Aspergillus galactomannan antigen, as well as molecular DNA sequencing techniques for identifying yeasts and filamentous fungi.132,133

Determining the antifungal sensitivity of fungi that produce peritonitis is not done systematically, except in the case of a few species known to be resistant or in the case of treatment failure. At present, we recognise the importance of determining the sensitivity of some yeast species to azolic compounds, as the development of resistant strains has been reported.6

TREATMENT

Treatment of fungal peritonitis is not clearly defined due to the low number of patients treated in the series we reviewed and the use of different antifungals, routes of administration, dose and treatment duration.

Recommendations by the International Society for Peritoneal Dialysis in 2005 and by the Spanish Society of Nephrology (SEN) in 2006 state that in addition to antifungal treatment, early removal of the catheter is fundamental to resolving the condition.25,134 It has been shown that symptoms persist up to 72 hours after administering antifungals in a large number of episodes. This is due in part to the ability fungi to form biofilms on the surface of catheters, which decreases the penetration of the drugs. It is therefore accepted that catheter removal is necessary in order to eradicate the infection, given that it is a primordial site for microbial colonisation; however, the best time to do so is not clear. Some authors recommend removing the catheter in the first 24 hours after administering the antifungal treatment and others recommend removal even without having administered treatment, stating that the mortality rate increases if the catheter is removed after 24 hours.5,8,9,13,15,18,25,26 The reinsertion of a new peritoneal catheter, where applicable, should be performed at least 4-6 weeks after the condition is resolved.1,9,26

In addition to the removal of the catheter, all protocols must include the administration of antifungal drugs by the peritoneal, oral or intravenous route. Treatment options for fungal peritonitis were limited up until the appearance of the new amphotericin B formulations, wide-spectrum triazoles and echinocandins, which are safer and have a better pharmacokinetic profile. At present, the antifungals available on the market include polyenes (amphotericin B), azolic derivatives (miconazole, ketoconazole, fluconazole, itraconazole, voriconazole, posaconazole, ravuconazole, isavuconazole), fluorated pyrimidines (fluorocytosine) and echinocandins (caspofungin, micafungin, anidulafungin). In isolated cases, terbinafin (from the allylamine group) has been used: this antifungal acts on dermatophyte fungi, C. albicans and Malassezia.92

Fluconazole has been considered the treatment of choice for years, due to its excellent penetration in the peritoneum, good bioavailability, the few adverse reactions that it provokes, and the possibility of administering it to patients on an outpatient basis.135 It has even been stated that treatment with oral fluconazole and the removal of the peritoneal catheter would be as effective as associating intraperitoneal fluconazole and oral 5-fluorocytosine.24 It is known that this antifungal is not effective for many of the filamentous fungi that cause peritonitis, especially Aspergillus and Fusarium. On the other hand, in recent years we have confirmed the appearance of Candida species that are resistant to fluconazole (C. krusei, C. ciferrii, C. norvegensis, C. glabrata, C. famata, C. lusitaniae, C. guilliermondii and C. tropicalis), as are other yeasts (Trichosporon), which indicates that it is not convenient to use fluconazole in monotherapy for certain peritonitis episodes, and that its effectiveness must be evaluated for some yeast species.25 The new triazoles, particularly voriconazole, are extremely useful in fungal peritonitis, whether by the oral or intravenous route, and even permit us to maintain the peritoneal catheter.73,136,137

Amphotericin B is a wide-spectrum antifungal drug; resistance has only been detected in vitro in a few species of yeasts and filamentous fungi, so it offers a certain amount of safety.46 One of its drawbacks is that intraperitoneal administration causes local irritation and does not enable it to reach a good inhibitory concentrations, which is why it is used intravenously.135,136 The liposomal formulation offers reduced toxicity without decreasing effectiveness. Primary resistance to amphotericin B has emerged in parallel with an increase in infections caused by certain yeasts (Trichosporon beigelii, C. lusitaniae, C. guilliermondii), hyaline filamentous fungi (Fusarium, Scopulariosis, Scedosporium) and some dematiaceous fungi.

Echinocandins are able to act upon biofilms, which could be another argument for their therapeutic indication in treating catheter-associated infections. They are administered by intravenous perfusion. Caspofungin is the most widely used, but its analogue anidulafungin is two to four times more active in vitro. The most important disadvantage of using chinocandins is that there is no method of reference for evaluating their in vitro activity on yeasts and filamentous fungi; for that reason, we must be prudent when extrapolating in vivo data.

The antifungal drugs currently used in clinical practice include the following: fluconazole (whether associated with 5-fluorocytosine or not), amphotericin B, voriconazole and caspofungin, either as monotherapy or in any of their possible combinations.4,9,28-30,90 Although monotherapy with fluconazole (200mg/day) is generally effective, combined treatment or use of more potent drugs can improve the prognosis and decrease mortality.100 For this reason, it is recommended in the event of treatment failure, resistance or intolerance to other antifungal drugs and episodes caused by filamentous fungi.13,25,29,56,138 Combined treatment with fluconazole allows us to reduce the dose to 100mg/day and reduce treatment time, which should generally be a minimun of 2 weeks minimum up to 4-6 weeks, according to different authors.

The usefulness of administering oral prophylactic treatment with fluconazole (100mg/day), ketoconazole (200mg/day) and nystatin (daily rinse) has been demonstrated for avoiding fungal proliferation in those patients with a high risk of infection due to prolonged antibiotic treatment, repeated peritonitis episodes or compromised immune systems.9,35,139-142 However, some studies do not confirm a decrease in fungal peritonitis episodes with the use of nystatin as a prophylactic.143-145

Some studies have shown a decrease in the bacterial peritonitis incidence rate with the new advances in peritoneal dialysis systems, the use of more biocompatible solutions (with no glucose degradation products and with bicarbonate or low lactate concentrations),138 our better understanding of risk factors and the use of preventative measures, but there is no data regarding fungal infection. It is possible that this fact, together with the early removal of the peritoneal catheter and the use of potent antifungal drugs, is a major contribution to the decrease in fungal peritonitis episodes in peritoneal dialysis patients.

Table 2. Dimorphic yeasts and fungi causing peritonitis in peritoneal dialysis

Table 1. Risk factors associated with peritonitis in peritoneal dialysis

Table 3. Filamentous fungi causing peritonitis in peritoneal dialysis