Antecedentes: La enfermedad cardiovascular (CV) es la principal causa de mortalidad en pacientes en terapéutica de reemplazo renal. El principal objetivo del estudio fue evaluar el perfil de riesgo CV y prevalencia de enfermedad CV en pacientes en diálisis peritoneal (DP) en Portugal. El segundo fue determinar los parámetros más relacionados con enfermedad CV. Métodos: Estudio retrospectivo, multicéntrico, de los adultos en DP. Se incluyeron seiscientos pacientes (56,7 % varones, edad media 53,5 ± 15,3 años), en DP por 25,6 ± 21,9 meses. Los pacientes se dividieron: grupo 1 (n = 166) con enfermedad CV y grupo 2 (n = 434) sin enfermedad CV. Las comparaciones se hicieron con los factores tradicionales de riesgo CV y los asociados a uremia y a propia DP; en el análisis multivariante se determinaron las variables asociadas de forma independiente a enfermedad CV. Resultados: Al final del estudio, la prevalencia de enfermedad CV fue del 28 %. En el análisis univariante, el grupo 1 presentó mayor frecuencia de varones (p < 0,01), pacientes de más edad (p < 0,01), diabéticos (p < 0,01), presencia de hipertrofia ventricular izquierda (HVI) (p < 0,01), mayor proteína C-reactiva (PCR) (p = 0,04), menor nivel medio de parathormona (p = 0,014), menor fósforo sérico (p = 0,02), menor diuresis diaria (p = 0,04), menor Kt/V semanal (p = 0,008), un mayor uso de icodextrina y soluciones a base de glucosa hipertónica (p < 0,001 y p = 0,006, respectivamente), con más enfermos sometidos a DP continua ambulatoria (DPCA) (p = 0,014) y tenían un transporte peritoneal alto (p = 0,02). El análisis multivariante demostró la influencia independiente de edad > 50 años, PCR > 0,6 mg/dl, sexo masculino, diabetes, HVI, DPCA y anuria. Conclusiones: Los factores de riesgo más relacionados con el desarrollo de enfermedad cardiovascular en la DP en Portugal son edad > 50 años, PCR > 0,6 mg/dl, sexo masculino, diabetes, HVI, DPCA y anuria.

Background: Cardiovascular (CV) disease is the major cause of mortality in patients undergoing renal replacement therapy. The primary aim of the study was to evaluate the CV risk profile and prevalence of CV disease in patients on peritoneal dialysis (PD) in Portugal. The secondary goal was to establish parameters most associated with CV disease. Methods: Retrospective, multicenter study of the prevalent adult population on PD. Six hundred patients were included (56.7% male; mean age 53.5±15.3 years), on PD for 25.6±21.9 months. Patients were divided into two groups: group 1 (n=166) with CV disease and group 2 (n=434) without CV disease. Comparisons were made regarding traditional CV risk factors and those associated with uremia and PD itself, and a multivariate analysis was performed to determine variables independently associated with CV disease. Results: At the end of the study, the prevalence of CV disease was 28%. At univariate analysis, group 1 presented a higher frequency of males (p<.01), older patients (p<.01), diabetics (p<.01), occurrence of left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) (p<.01), mean C–reactive protein (CRP) (p=.04), lower mean parathormone level (p=.014), lower serum phosphorus (p=.02), lower daily urine output (p=.04), lower weekly Kt/V (p=.008), increased use of icodextrin and hypertonic glucose-based PD solutions (p<.001 and p=.006, respectively) and more were under continuous ambulatory PD (CAPD) (p=.014) and had a high peritoneal transport status (p=.02). Multivariate analysis provided a significant discriminatory influence pertaining to age >50 years, CRP>0.6mg/dl, male gender, diabetes, LVH, CAPD and anuria, when comparing group 1 and group 2. Conclusions: Risk factors most related to the development of CV disease in PD in Portugal are age >50 years, CRP>0.6mg/dL, male gender, diabetes, LVH, CAPD and anuria.

INTRODUCTION

Cardiovascular (CV) disease is the leading cause of death in patients needing renal replacement therapy (RRT) and is a substantial cause of morbidity in this population.1 Chronic kidney disease (CKD) patients present with a CV disease death rate that is 5 to 25 times higher than that seen in the general population.2 CV disease is often present at the start of RRT, but may also develop during chronic dialysis.3,4

The development of atherosclerosis in patients on peritoneal dialysis (PD) arises from the interaction of several risk factors that can be systematized into three groups: (i) traditional risk factors: hypertension, diabetes mellitus, smoking, sedentary lifestyle, lipid abnormalities and obesity; (ii) factors related to stage 5 CKD: inflammation, malnutrition, endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress, vascular calcification, insulin resistance, hyperhomocysteinemia and anemia; (iii) and PD-specific factors: volume overload, loss of residual renal function (RRF) and formation of advanced glycation end-products.5

According to data provided by the Portuguese Society of Nephrology, at the end of 2010 in Portugal, 10,788 patients were being treated with dialysis for stage 5 CKD – 94% on hemodialysis (HD) and 6% on PD. The major causes of death that year among dialysis patients were CV disease in general and infectious complications not related to the vascular access or peritoneal catheter. In Portugal, the available data on CV disease in peritoneal dialysis patients are scarce. For this reason, the authors designed a retrospective, observational cross-sectional study with the aim of evaluating the CV risk profile and prevalence of CV disease in the adult population on PD. The secondary goal was to establish clinical and laboratorial parameters most associated with the presence of CV disease in this population.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

The study cohort was composed of all prevalent adult patients (age ≥18 years) undergoing PD in Portugal on 31 December 2010. The patients were recruited from all 18 Portuguese PD Units. Demographic and clinical data were registry-based and retrospectively collected. Each PD unit was responsible for the collection and submission of individual patient data. The data included gender, age, comorbid medical conditions, medication, body mass index (BMI), daily urinary output (measured at monthly routine appointments) and PD-related variables (modality, duration of PD, use of icodextrin or hypertonic glucose-based solutions and peritoneal membrane transport type measured by the dialysate-to-plasma (D/P) creatinine ratio at the fourth hour of a standard peritoneal equilibration test performed every six months). Recorded laboratory data were based on samples collected for monthly routine examinations and included: dialysis adequacy data (total Kt/V urea and total weekly creatinine clearance), total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, triglycerides, C-reactive protein (CRP), serum calcium, serum phosphorus and parathormone level. Hypertension was defined as a systolic blood pressure above 140mmHg or diastolic blood pressure above 90mmHg and/or need for antihypertensive medication. CV disease was defined as a history of coronary, cerebrovascular and/or peripheral artery disease, and/or of congestive heart failure. Coronary disease was defined as a previous history of angina, myocardial infarction, angioplasty, or coronary artery bypass graft. Cerebrovascular disease was defined as a previous transient ischemic attack or stroke, and peripheral vascular disease as a history of claudication, ischemic limb loss, and/or ulceration or a peripheral revascularization procedure. Congestive heart failure was defined by the clinical evidence of volume overload (dyspnea, peripheral edema, pleural effusion, and/or ascites) and/or a left ventricular fractional shortening of less than 30% on echocardiography, performed once a year in all patients. The patients were divided into two groups regarding the presence (group 1; n=166) or absence (group 2; n=434) of CV disease on 31 December 2010 and comparisons were made with relation to traditional Framingham CV risk factors, and risk factors associated with uremia and PD itself.

All statistical analyses were performed using the commercially available SPSS® for Windows® (version 17.0, Chicago, IL, USA). Continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and categorical variables as a percentage of the number of studied cases. Univariate testing of variables between two independent groups was performed using the t test or Mann-Whitney test for continuous variables and the χ2 test for nominal variables. A multivariate analysis by logistic regression, using a backwards approach, was performed to highlight the independent association of the presence of CV disease with different variables. Odds ratios are provided for independent nominal variables associated with the presence of CV disease. A two-tailed p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

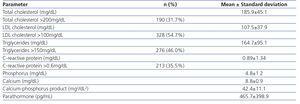

The study sample was composed of all 600 patients treated at all 18 PD units throughout Portugal, the majority being of the male gender (56.7%; n=340) with a mean age of 53.5±15.3 years, on PD for a mean duration of 25.6±21.9 months, ranging from 0.1 to 136.4 months (continuous ambulatory PD [CAPD] in 47.7% and automated PD [APD] in 52.3%). Most patients (83.2%; n=499) were on PD by personal choice, while 14.8% (n=89) transferred from HD after failure of vascular access for HD and 2.0% (n=12) due to hemodynamic instability on HD. Twenty-four of the 600 prevalent patients on PD proceeded from a failed kidney transplant (21 of these patients started PD by personal choice and three started PD due to previously documented failure of an available vascular access for HD), corresponding to 4% of the total population. The majority of patients used PD solutions with a bicarbonate buffer (92.2%), 49.7% required icodextrin and 7.3% utilized hypertonic glucose solutions. Mean daily urinary output was 1,045.6±827.2mL and 125 patients (20.8%) were anuric. The standard peritoneal equilibration test determined 4.0% of PD patients as having low peritoneal membrane transport status, 33.6% as low-average, 47.9% as high-average and 14.5% as high peritoneal membrane transport status. Average weekly Kt/V urea was 2.28±0.59 and weekly creatinine clearance was 93.6±45.8L/1.73m2. Patients´ general biochemical characteristics are described in Table 1.

At the initiation of PD, CV disease was documented in 138 patients (23%) - ischemic cardiopathy (52.2%; n=72), congestive heart failure (10.9%; n=15), cerebrovascular disease (26.8%; n=37) and peripheral arterial disease (10.1%; n=14).

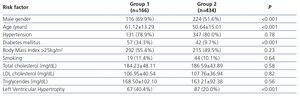

Among the traditional CV risk factors, 79.7% of all patients presented with hypertension, 51.2% were overweight (measured as a BMI>25kg/m2; average BMI was 25.6±4.3kg/m2) and 2.3% had a BMI<18.5kg/m2, 16.5% were diabetic and 10.5% were smokers. Left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) was present in 25.7% of patients on echocardiographic evaluation and mean fractional shortening was 37.4±6.9%. At the end of the study period, the 28% of the patients presenting with documented CV disease (n=166) showed evidence of ischemic cardiopathy (49.4%; n=82), congestive heart failure (11.4%; n=19), cerebrovascular disease (27.7%; n=46) and peripheral arterial disease (11.4%; n=19).

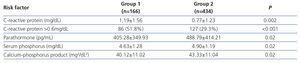

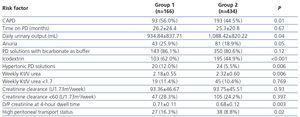

Results of a univariate analysis comparing the association of the variables in patients with and without CV disease are displayed in Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4. Variables associated with CV disease (p<.05) at the univariate analysis were male gender, older age, diabetes, LVH on echocardiography, higher CRP levels, lower serum parathormone level, lower serum phosphorus level, PD modality (in particular, CAPD), lower average daily urinary output, use of icodextrin or hypertonic glucose-based PD solutions, lower weekly Kt/V and high peritoneal membrane transport status (D/P creatinine at a 4-hour dwell between 0.81 and 1.03). Anuria fell just marginally short of reaching statistical significance on univariate analysis (p=.05).

A multivariate analysis by backwards binary logistic regression was performed to highlight the factors independently associated with the presence of CVD in our PD population and the variables with the strongest association were age above 50 years (OR 3.47, CI95% 2.04 to 5.89, p<.0001), CRP>0.6mg/dL (OR 2.99, CI95% 1.84 to 4.86, p<.0001), male gender (OR 2.54, CI95% 1.53 to 4.23, p<.0001), diabetes mellitus (OR 2.54, CI95% 1.52 to 4.23, p<.0001), LVH (OR 2.47, CI95% 1.47 to 4.15, p=.001), CAPD (OR 2.18, CI95% 1.31 to 3.63, p=.003) and anuria (OR 2.11, CI95% 1.15 to 3.89, p=.017). A CRP measurement above 0.6mg/dL was used as the cut-off value for the multivariate analysis since this value corresponded to the upper limit of normal in our hospital laboratory. The remaining variables associated with CV disease in univariate analysis lost statistical significance in multivariate analysis.

DISCUSSION

It is broadly recognized that age, gender, high blood pressure, smoking, lipid abnormalities, and diabetes mellitus are major risk factors for the development of CV disease.6

Hypertension is highly prevalent in patients with CKD, although it varies in PD populations from 29 to 80%7 where it is typically associated with inadequate control of fluid overload.8,9 Hypertension is strongly correlated with LVH and changes in cardiac structure tend to progress during RRT.10,11 Our multicenter study showed a high prevalence of hypertension in our population (79.7%), thus corroborating previous publications, and LVH was one of the factors identified by multivariate analysis that related significantly to the presence of CV disease, present in 40.4% of patients with CV disease and 20.0% of those without CV disease. Findings surrounding the relationship between hypertension and CV mortality have been contradictory,12-14 but a meta-analysis of randomized studies published in 2009 by Heerspink et al.15 showed that treatment of patients on chronic dialysis therapy with antihypertensive medication reduced their high CV morbidity and mortality rates.

Conventional PD solutions are glucose-based and this glucose is readily absorbed across the peritoneal membrane, leading to an increased circulating glucose load and weight gain in many patients, accompanied, in some cases, by the development of diabetes mellitus.16 Insulin resistance is common and a well-known risk factor for CV disease in the CKD (and PD) population.16,17 New-onset diabetes after initiation of PD is associated with worse survival. This was noted by Szeto CC et al.18 in a study of 405 incident PD patients where, after 36 months of therapy, actuarial survival rates were 93.7%, 85.3%, 81.6%, and 66.7% for patients with fasting glucose levels <100, 100-125, 126-199, and ≥200mg/dL and 65.9% for patients with preexisting diabetes, respectively (overall log rank test, p<.001). In our study, 99 patients were diabetic and CV disease was more prominent among the diabetic PD population on both univariate and multivariate analyses.

Another cardiovascular risk factor specific to peritoneal dialysis arises from the presence of glucose degradation products in conventional peritoneal dialysis solutions, leading to formation of advanced glycation end products.4 The cardiovascular and overall mortality impact related with the decrease in plasma advanced glycation end product concentration associated with biocompatible dialysis solutions is unknown. Better survival has been described in retrospective but not randomized studies. These solutions may, however, reduce peritoneal neoangiogenesis and thereby attenuate the risk of ultrafiltration failure that ultimately leads to hypertension and volume overload.19 Several studies have suggested clinical benefits of icodextrin regarding fluid management amongst other benefits, including improved glycemic and metabolic control. A recent study by Han et al. enrolled 2,163 PD patients and determined that patients receiving an icodextrin prescription for more than 50% of their PD duration, although not statistically different in terms of cardiovascular comorbidity from their counterparts, experienced fewer deaths and technique failure due to non-compliance. The authors in that publication alert for the need for randomized trials to confirm and better evaluate these findings.20

APD has been increasingly used in many parts of the world, essentially due to lifestyle flexibility offered by this modality of PD and not only medical concerns (for example, lower incidence of peritonitis, fewer mechanical complications, faster decline in RRF and less sodium removal eventually associated with APD) or financial burden.21 In our cohort, 52.3% of the prevalent PD patients used APD. Ortega et al. observed slightly improved blood pressure control in CAPD patients (although no significant relationship between blood pressure values and amount of peritoneal sodium removal was found),22 however, in contrast, a study by Rodríguez-Carmona and Fontán observed higher blood pressure in CAPD patients despite statistically significant higher sodium removal.23 Similar patient and technique survival has been shown between APD and CAPD in the United States, Europe and in Australia and New Zealand,24-26 however two large observational studies (by Guo et al. and Sanchez et al., published in 2003 and 2008, respectively) showed a survival benefit for APD.27,28 Only three randomized controlled trials comparing APD to CAPD have been published and the number of patients was relatively small, but no significant differences in survival were found.29 Appraisal of outcomes between PD modalities is made difficult by the variability of PD prescriptions, however a study aimed at looking at the differences between the modalities (with regard to baseline health status, detailed comorbidity scoring and other factors) is warranted in our population before making assumptions on the relationship between CV disease or risk and APD or CAPD, despite the independent association found between CAPD and CV disease found in our study. Nonetheless, large randomized controlled trials are necessary to determine the possible association between CV disease and PD modalities.

It is readily accepted that patients on dialysis are at an increased risk for accelerated atherosclerosis, in part due to the existence of inflammation which is multifactorial in nature (infections, malnourishment, bioincompatible dialysis solutions and CV disease).30 Studies have verified the importance of inflammation, as represented by CRP, in predicting CV death in dialysis patients,31 as well as in predicting the time to occurrence of cardiac events in these patients.32 There is an important inverse relationship between inflammation and RRF to be noted in PD patients,33 as can be established by the presence of higher serum levels of CRP in anuric PD patients when compared to those with preserved RRF.34 Published reports have shown that elevated CRP is an independent risk factor for both nonfatal cardiac events and for an increased incidence for CV disease,5,35 with PD patients in the upper CRP quartile presenting with a CV risk that is 5 times that of patients in the lower quartile.35 For every increase of 10mg/L of CRP, the relative risk of death has been shown to increase 2.69 times, independent of CV disease, age, serum albumin, diabetes and RRF.36 In our population, average CRP was 0.89±1.34mg/dL, with 213 patients (35.5%) presenting with a serum CRP level above 0.6mg/dL. Those with CV disease had a higher CRP when compared to those without CV disease (1.19±1.56 vs. 0.77±1.23mg/dL; p=.002), and patients with a serum CRP level above 0.6mg/dL were 2.64 times more likely to have CV disease.

Hyperphosphatemia and an increased calcium-phosphorus product are well-known risk factors for mortality and CV death in both HD and PD patients,37 also contributing to an enhanced risk of vascular, valvular and other tissue calcifications.38 The significance of these vascular calcifications in foreseeing mortality and CV death has been demonstrated in HD patients39 and they are also a potent predictor of CV death and overall mortality in PD patients.40 Calcification of the medial layers is linked with widespread arterial stiffening, thereby increasing the afterload and consequently resulting in LVH, which may, in turn, increase the risk of myocardial ischemia by reducing coronary flow reserve.38 Nevertheless, in our population, patients with CV disease had significantly lower serum phosphorus levels than those without CV disease (4.63±1.28 vs. 4.90±1.19mg/dL, p=.02), possibly an indicator of malnutrition, also a known risk factor for CV disease.

RRF in PD patients may play an important part in extracellular volume control. Fluid overload may be explained by the loss of RRF, which is in itself a significant predictor of mortality,33 as well as contribute to the development of LVH in these patients.38 Reanalysis of data from the cohort of 601 incident patients on PD from the CANUSA study published in 2001 showed that RRF and urine volume were more vital contributors to overall survival of PD patients than PD clearance was.41 In the ADEMEX study, which was a prospective, randomized, controlled trial in 965 prevalent PD patients published in 2002, for each 10 liters per week per 1.73m2 increase in RRF, there was an 11% decrease in the relative risk of death.42 These results were confirmed by the NECOSAD study, a prospective multicenter study in the Netherlands.14 A prospective study by Wang et al. in 246 CAPD patients, 39% of which were completely anuric, demonstrated more adverse CV, inflammatory, nutritional and metabolic profiles and a higher overall mortality in the anuric population when compared to those patients with a residual glomerular filtration rate ≥1mL/min/1.73m2.34 Our patients had a mean urinary output of 1,045.6±827.2mL and 20.8% were anuric. A statistically significant difference was found between patients with CV disease and those without CV disease on univariate analysis with regard to daily urine output (934.84±837.71mL vs. 1088.42±820.22mL, p=.04). On univariate analysis anuria closely approached statistical significance (25.9% vs. 18.9%, p=.05), while on multivariate analysis it proved to be an independent predictor of CV disease in the Portuguese PD population.

Limitations to this study include its retrospective nature, which can be a source of bias and confound, and the fact that prevalent patients may not be representative of all cases. In fact, it is possible that by studying only the prevalent PD population on 31 December 2010, many patients who potentially transferred to HD (or transplantation) or died due to CV disease were overlooked, thereby underestimating the true prevalence of CV disease in Portugal. Clinically subjective definitions for the various types of CV disease are another probable source of misconception regarding the prevalence of CV disease. Additionally, treatment or correction of identified fluid overload could reverse congestive heart failure, thereby ameliorating the condition and explaining the low prevalence of congestive heart failure on 31 December 2010 in our population, however this was not addressed specifically.

In conclusion, our multicenter study showed that in the Portuguese PD population, the factors independently associated with CV disease were age above 50 years, CRP>0.6mg/dL, male gender, diabetes mellitus, LVH, CAPD and anuria. Although certain risk factors for CV disease, such as older age and male gender, are not modifiable, nephrologists need to be conscious of those disorders whose management could diminish the pronounced burden of CV disease existent in this population, in order to reduce the high morbidity and mortality rates and thus improve long-term outcomes in the PD population.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest associated with this manuscript.

Table 1. Laboratory data of the prevalent population on peritoneal dialysis (n=600).

Table 2. Traditional risk factors associated with the presence of cardiovascular disease.

Table 3. Risk factors related to chronic kidney disease associated with the presence of cardiovascular disease.

Table 4. Risk factors related to peritoneal dialysis associated with the presence of cardiovascular disease.