To the Editor,

Kidney transplant recipients have a greater risk of developing tuberculosis, commonly being atypical and extrapulmonary. We present the case of two patients submitted to kidney transplant with extrapulmonary tuberculosis in an uncommon localisation.

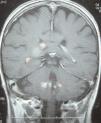

A 66-year-old female, with chronic kidney failure secondary to hepatorenal polycystosis, which received a deceased-donor kidney transplant and treatment with basiliximab, steroids, mycophenolate mofetil and tacrolimus. She suffered a type IIb cortical-resistant acute rejection and needed treatment with OKT3. After four months she was admitted for fever, general discomfort and intense asthenia. She was diagnosed with suspected pulmonary tuberculosis by chest computed tomography (CT) and fibrobronchoscopy, confirmed by Ziehl-Neelsen staining and Löwenstein culture. She was prescribed treatment with rifampicin, isoniazid and pyrazinamide for two months, followed by rifampicin and isoniazid for four months. After 15 days she was readmitted for confusion, occipital cephalgia and visual alterations. In a brain resonance, multiple hypertensive nodules were seen in T2, with nodular focal contrast in the right frontal, subcortical, suprasylvian, right occipital areas and in cerebellar peduncles, indicative of granulomatous infiltration secondary to tuberculosis (Figure 1). Treatment with isoniazid and rifampicin was extended to nine months and the patient recovered.

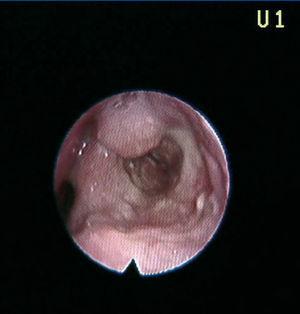

A 41-year-old male, diagnosed with hepatorenal polycystosis received a deceased-donor kidney transplant with immunosuppression with cyclosporin and steroids. He suffered a grade IIb acute interstitial rejection, treated with three boli of 500mg of 6-methylprednisolone. Three and 9 years after the transplant he presented with two episodes of dysphonia; on both occasions with whitish lesions on the arytenoid cartilages and the epiglottis. Anatomopathological diagnosis was tuberculoid granulomatous chronic laryngitis (Figure 2). The Ziehl-Neelsen staining and Löwenstein test were positive. The patient received treatment with isoniazid, rifampicin and pyrazinamide for 2 months and isoniazid and rifampicin for 9 months.

Tuberculosis in organ recipients is considered to be an opportunist infection in most cases, given that it reactivates latent infection with an incidence of 20 to 70 times more than in the general population. In Europe it is from 0.07% to 1.7%, with a mortality rate of 20%-30%.1

Although immunosuppression for kidney transplantation is less intense than for other organs, it is associated with greater risk of tuberculosis, given that the T cells’ function is particularly altered due to uraemia and because of a greater exposure to the infection in the dialysis units.2

The fact that the disease spreads in 30% of cases, and anti-rejection treatment helps the infection become localised in unsuspected sites, which could make diagnosis more difficult and postpone treatment.3

Diagnosing latent infection by the tuberculin test presents many false negatives. The measurement of the interferon gamma response to the T cells stimulated by the M. tuberculosis antigens (Quantiferon TB gold) may be more sensitive than the previous one.4

It is advisable to treat patients with latent tuberculosis before they undergo transplantation with isoniazid at a dosage of 300mg/day for 9 months. In the same way, for patients that have recently undergone transplant, prophylaxis with isoniazid is recommended for at least 6 months if it is suspected that they had a previous infection.5

Treating the active infection does not differ from the usual treatment, although we must consider that certain drugs must be adjusted in presence of kidney failure and that others alter the P450 cytochrome, which means that they could interact with immunosuppressive drugs that use this enzymatic system, mainly calcineurin inhibitors and antimammalian target of rapamycin (MTOR) agents.5

Our patients presented with a tuberculous infection in an uncommon localisation, favoured by the kidney transplantation immunosuppression and the anti-rejection treatment. Treatment was effective to control the disease.

Figure 1. Cerebral tuberculoma

Figure 2. Tuberculous laryngitis