We present the case of a 23-year-old man with a 3-month history of headache, loss of vision, loss of appetite, and foamy urine. In the previous week, he had been bedridden, with sensory disturbances, oliguria, and dyspnoea. Upon initial assessment he appeared generally unwell, drowsy, disorientated, tachycardic, hypertensive, and tachypnoeic. He had asterixis, uraemic breath, jugular venous distension, breath sounds with bibasal rales, and oedema of lower limbs. Lab test on admission showed elevated nitrogen products, metabolic acidosis with a wide anion gap, evidence of non-immune microangiopathic haemolytic anaemia and thrombocytopenia (Table 1). Further tests were requested, including ADAMTS13 activity, and infection and immune profiles, which were negative (Table 1). Treatment was started with haemodialysis, parenteral labetalol, red cell transfusion, and plasma exchange. Once uraemia and hypertensive crisis were controlled, ophthalmological examination revealed a marked loss of visual acuity (RE: 20/400+1; LE: 20/150−1) and hypertensive retinopathy. On day 7, haemolytic activity was controlled, which allowed discontinuation of plasma exchanges. However, the patient relapsed 48h later, plasma exchanges were restarted and a definitive diagnosis was made of aHUS (Fig. 1). Treatment with eculizumab was initiated, and plasma exchanges were stopped. The patient made adequate progress, with recovery of vision (20/30 in both eyes), however, dialysis had to be maintained. Genetic studies to detect complement mutations associated with aHUS were negative (Table 1). At 9 month follow-up, the patient remained dialysis-dependent; therefore, a diagnosis was made of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) secondary to aHUS, and the workup for renal transplantation was initiated.

Laboratory results.

| Urine cytochemistry | Appearance | pH | Density | Proteinuria | Red blood cells | Leucocytes | Proteinuria |

| Turbid | 8 | 1.015 | >300mg/dL | >50/HPF | 21–50/HPF | 850mg/day | |

| Capillary gases | pH | HCO3 | PCO2 | PO2 | PaO2/FiO2 | Lactate | Base excess |

| 7.24 | 9.6mmol/L | 22mmHg | 121mmHg | 242 | 1.3mmol | −15.7mmol/L | |

| Renal and metabolic profile | Creatinine | BUN | Uric acid | Sodium | Potassium | Chloride | Phosphorus |

| 19.7mg/dL | 128mg/dL | 8.5mg/dL | 140mEq/L | 4.2mEq/L | 100mEq/L | 8mg/dL | |

| Corrected calcium | Ionised calcium | Magnesium | Albumin | Glucose | Total cholesterol | HDL-cholesterol | |

| 6.7mg/dl | 0.65mmol/L | 1.53mg/dL | 2.8g/dL | 92mg/dL | 108mg/dL | 31mg/dL | |

| LDL-cholesterol | Triglycerides | Vitamin D | PTH | Vitamin B12 | Ferritin | Folic acid | |

| 63.6mg/dL | 61mg/dL | 19.3ng/mL | 751pg/mL | 286pg/mL | 551ng/mL | 7.7ng/mL | |

| Haematological profile | Haemoglobin | Haematocrit | Leucocytes | Neutrophils | Lymphocytes | Monocytes | Basophils |

| 5.1g/dL | 14% | 6.200mm3 | 80.2% | 11.3% | 8.1% | 0.4% | |

| Eosinophils | Platelets | Corrected reticulocytes | PBF | LDH | Haptoglobin | ADAMTS13 activity | |

| 0% | 82,000mm−3 | 5.2% | Schistocytes ++ | 547U/L | 10.6mg/dL | 74.5% | |

| PTT | PTT control | PT | INR | Fibrinogen | |||

| 30s | 26.1 | 11.3s | 1.04 | 435mg/dL | |||

| Liver profile | TB | DB | IB | AST | ALT | ALP | |

| 1.5mg/dL | 0.4mg/dL | 1.1mg/dL | 22U/L | 18U/L | 77U/L | ||

| Immunological studies | C3 | C4 | ANA | ENA | MPOAb | PR3Ab | Direct Coombs |

| 106mg/dL | 28.8mg/dL | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | |

| Complement genetic study | No pathological mutations were found for: ADAMTS13, C3, CD46, CFB, CFH, CFHR1, CFHR2, CFHR3, CFHR4, CFHR5, CFI, DGKE, PIGA, THBD | ||||||

| Other investigations | Protein electrophoresis | HIV | Hepatitis B | Hepatitis C | VDRL | Renal biopsy | |

| Hypoalbuminemia, non-specific elevation of alpha 1 band and B2 | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | Thrombotic microangiopathy | ||

| Plain CT head | Echocardiography | Renal ultrasound | |||||

| Normal | Pulmonary hypertension and mild pericardial effusion | Small echogenic kidneys with loss of corticomedullary differentiation | |||||

ALP, alkaline phosphatase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; ANA, antinuclear antibodies; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; C3, complement C3; C4, complement C4; CT, computed tomography; DB, direct bilirubin; ENA, antibodies against the extractable nuclear antigens anti-RNP, -Sm, -Ro, and -La; HCO3, serum bicarbonate; HDL cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus antibody; HPF, high-power field; IB, indirect bilirubin; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; LDL cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; MPOAb, anti-myeloperoxidase antibodies; PBF, peripheral blood film; PCO2, partial pressure of carbon dioxide; PO2, partial pressure of oxygen; PR3Ab, anti-proteinase 3 antibodies; PTH, parathyroid hormone; TB, total bilirubin; VDRL, non-treponemal test for syphilis.

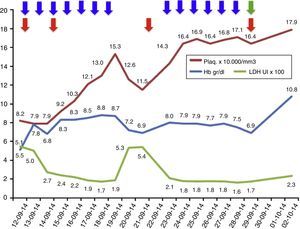

Results of laboratory investigations during treatment.

Laboratory parameters during treatment: 13 sessions of plasma exchange (blue arrows); total 4 red cell transfusions (red arrow); eculizumab, started on 29 September 2014 (green arrow). The LDH values are at a scale of 1×102 and the platelet values are at a scale of 1×104.

Atypical HUS is an extremely rare chronic genetic disease. It is caused by an abnormality in the regulation of complement and can lead to severe sequelae in multiple organs and even death.1–4 It is characterised by the triad of microangiopathic haemolytic anaemia, thrombocytopenia, and renal failure, though it can affect any organ.1,2 Our patient displayed renal, haematological, neurological, cardiovascular, and ocular involvement; ocular damage is not frequently reported in the literature.1,2

In more than half of the patients with aHUS, it is possible to identify the complement mutation or the mutation in other molecules leading to abnormal complement regulation. However, genetic study is not necessary for diagnosis and initiation of therapy. However genetic studies should be performed to establish prognosis, as some mutations are more aggressive than others. Moreover, genetic study allows more adequate strategy for renal transplantion.1,2,5 Up to 30% of patients have no documented genetic mutation,4,6 as it was the case in our patient.

The treatment of choice for aHUS is eculizumab, a humanised monoclonal antibody that blocks the cleavage of the C5 component of complement, thus preventing the release of the anaphylatoxin C5a and the formation of the membrane attack complex C5b-9. This prevents endothelial damage and the generation of thrombotic microangiopathy.1,7,8 As a prerequisite for starting eculizumab, the patient must be vaccinated against meningococcus and start antibiotic prophylaxis directed against meningococcus whilst the vaccine becomes effective. The earlier eculizumab is started in patients with aHUS, the higher the likelihood of recovery and the fewer sequelae.5,9 Nonetheless, whilst the diagnosis of aHUS is being established, plasma exchanges can stabilise the patient's haemolytic activity, therefore these should be started early if the clinical picture is one of a thrombotic microangiopathy. It should be kept in mind that blood samples should be obtained for ADAMTS13 activity and autoantibody profile prior to plasma exchange to avoid missing other diagnoses.1,5,7 If the definitive diagnosis is aHUS, treatment should be changed to eculizumab, as long-term plasma therapy has not been shown to change the devastating course of aHUS.1,5,9,10 In our patient, plasma exchanges were performed initially, achieving control of haemolytic activity; once the diagnosis of aHUS was established, treatment was changed to eculizumab, achieving a good response with no further need for plasma exchange and no further relapses (Fig. 1). However, the patient was left with the sequela of ESRD.

ConclusionAtypical HUS is a rare genetic disease that affects children and adults, characterised by the presence of non-immune microangiopathic haemolytic anaemia, thrombocytopenia and multi-organ damage. The clinical course can be devastating and endanger patients’ life and quality of life, leaving them with severe sequelae such as ESRD. Treatment with eculizumab must be started early to halt multi-organ damage and avoid death.

Conflicts of interestDr Nieto-Ríos and Dr Serna-Higuita have delivered conferences sponsored by Alexion Pharma. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest with the content of this article.

Please cite this article as: Nieto-Ríos JF, Serna-Higuita LM, Calle-Botero E, Ocampo-Kohn C, Aristizabal-Alzate A, Zuluaga-Quintero M, et al. Síndrome hemolítico urémico atípico en un paciente joven con compromiso renal, neurológico, ocular y cardiovascular. Nefrologia. 2016;36:82–85.