Persistent left superior vena cava (PLSVC), although rare, is the most common thoracic venous anomaly.1 It results from persistence of the embryonic left anterior cardinal vein and is considered a normal variant.2 The clinical significance depends mostly on the drainage site, and in 80%–90% of cases the drainage occurs to the coronary sinus (CS).3 We present a case of PLSVE incidentally detected after dysfunctional maturation of an arteriovenous fistula (AVF).

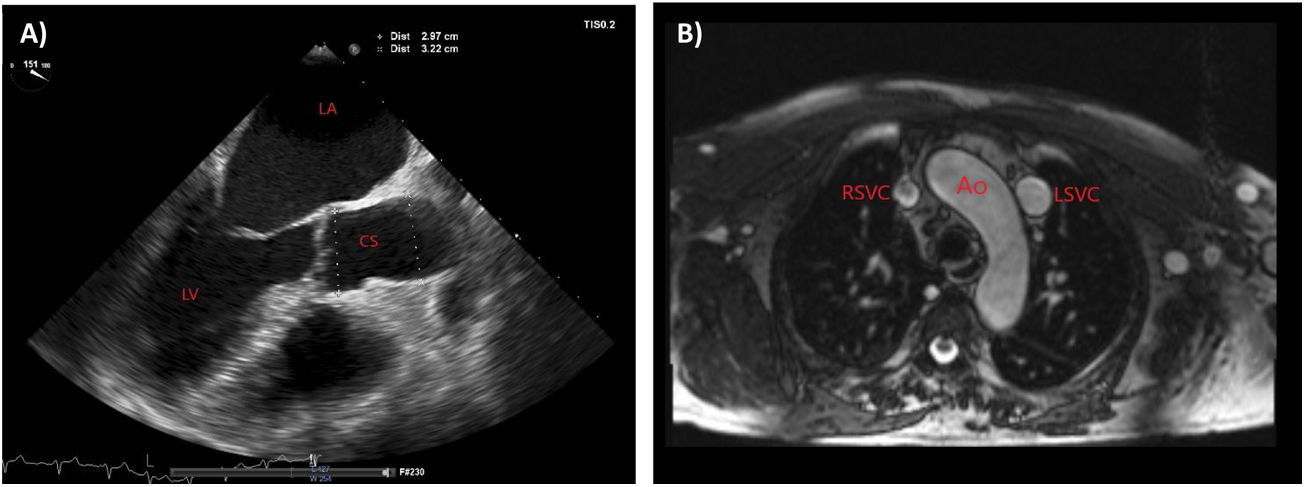

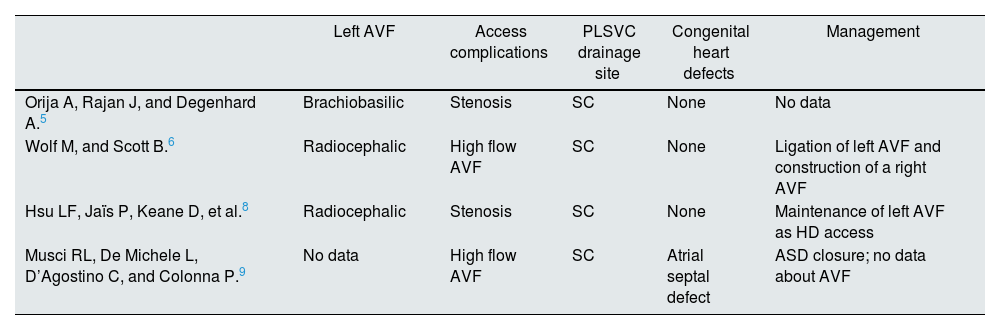

A 68-year-old man with stage 4 chronic kidney disease of undetermined etiology with a left radiocephalic AVF created 11 years back but never used for dialysis access. He also has atrial fibrillation (AF) that was been diagnosed three years after AFV creation. Aneurysmal and serpiginous dilatation was found throughout the fistulous tract, with evidence of collateral circulation and edema of the left upper limb. Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) showed normal left ventricular function, enlargement of left and right atrium, and a markedly dilated CS (33–35mm of transverse diameter) (Fig. 1A). The presence of a PLSVC draining into the right atrium through a volume-overloaded CS was confirmed by use of saline contrast (“bubble study”) echocardiography and by magnetic resonance imaging (Fig. 1B). Since the CS dilatation caused by volume overload due to draining of the PLSVC was presumably aggravated by the left sided AVF and the unknown risk of rupture in these cases, the arteriovenous access was ligated.

Imaging findings. (A) Transthoracic echocardiography showing a markedly dilated coronary sinus, and enlargement of left and right atrium. (B) Magnetic resonance imaging in transversal view showing a bilateral superior vena cava with a right superior vena cava and a persistent left superior vena cava. Ao, aorta; CS, coronary sinus; LA, left atrium; LSVC, left superior vena cava; RA, right atrium; RSVC, right superior vena cava.

PLSVC occurs in approximately 0.3%–0.5% of the population.2 Left superior vena cava (SVC) commonly coexists with right SVC, and it drains into the right atrium through the CS with no major hemodynamic effect.1,3 The clinical significance of PLSVC also depends on the accompanying anomalies. The most common associated congenital heart defects are single ventricle, atrioventricular septal defect, and tetralogy of Fallot.2,3 This anomaly should be suspected whenever a dilated CS is found on TTE and diagnosis can be confirmed by use of saline contrast echocardiography.1

Although PLSVC is mostly asymptomatic, the creation of an AVF in the left upper limb not only increases the amount of blood drained into the CS – which under normal conditions corresponds to only 20% of the total venous drainage3 – but also increases the pressure at the level of this vascular bed. The enlargement of the CS, which can reach the aneurysmatic level, may cause compression of the sinus/atrioventricular node and His bundle, leading to cardiac arrhythmias such atrial and ventricular fibrillation.2–6 In fact, PLSVC plays a considerable role in induction and maintenance of AF.7 This fact could explain the development of AF after AVF construction in our patient. An atrioventricular flow obstruction, with consequent decreased cardiac output, may also occur secondary to the compression of the left atrium by the dilated CS.6 In this scenario, the patient can develop symptoms of cardiac failure, particularly when there is a high-flow AVF draining into CS. Otherwise, hemodynamic alterations with development of more turbulent flow can cause intimal hyperplasia and lead AVF stenosis5 or compromise AVF maturation.

There were only found four case reports of a PLSVC coexisting with a left sided AVF5,6,8,9 (Table 1), in two main databases (PubMed and Google Scholar). All cases were accidental findings. AVF was being used for dialysis access in four patients – in two of those there was a high-flow AVF,6,9 and in the other two a stenosis in AVF.5,8 Only one patient was symptomatic, presents with dyspnea on exertion. In this case, there was a high-flow AVF (Qa 3000mL/min) which, presumably, would be causing an overload of volume and pressure in the CS justifying the patient's symptoms. This was the only case where the AVF was ligated and a new AVF was constructed.6

Summary of previously reported cases of a PLSVC coexisting with a left sided AVF.

| Left AVF | Access complications | PLSVC drainage site | Congenital heart defects | Management | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Orija A, Rajan J, and Degenhard A.5 | Brachiobasilic | Stenosis | SC | None | No data |

| Wolf M, and Scott B.6 | Radiocephalic | High flow AVF | SC | None | Ligation of left AVF and construction of a right AVF |

| Hsu LF, Jaïs P, Keane D, et al.8 | Radiocephalic | Stenosis | SC | None | Maintenance of left AVF as HD access |

| Musci RL, De Michele L, D’Agostino C, and Colonna P.9 | No data | High flow AVF | SC | Atrial septal defect | ASD closure; no data about AVF |

In summary, end-stage kidney disease patients are particularly vulnerable to complications from the PLSVC. Not only the coexistence of this anomaly with a left sided AVF may be a problem, but also central venous catheterization through the PLSVC into CS can cause potentially fatal complications (hypotension, perforation, cardiac tamponade, and cardiac arrest). For this reason, clinicians must be especially alert to this anomaly when planning a dialysis access. Besides the ultrasonographic vascular mapping, a TTE performed with attention to the CS might be useful.

Although this issue was addressed for the first time in the 2019 KDOQI guidelines for vascular access, there are no recommendations for how to act in a PLSVC coexisting with a left sided AVF. Guidelines only remember the possibility of this anomaly occurring when choosing the internal jugular veins for catheterization.

Considering the possible hemodynamic effects on CS dilatation and AVF maturation, it seems wise to avoid a left sided AVF in the presence of a PLSVC. However, further studies are warranted given the lack of sufficient data on this common and potentially complex finding.