A 59-year-old woman without relevant past medical history presented with hematuria and renal colic. After a negative diagnostic work-up, sickling vaso-occlusive crisis in the setting of sickle cell trait (SCT) was diagnosed. This report aims to raise awareness that SCT should be included in the differential diagnosis of unexplained hematuria and/or renal colic.

Renal abnormalities are frequently described in patients with sickle hemoglobinopathies, but SCT patients (heterozygous carriers, with one sickle cell gene and one normal gene) are mostly asymptomatic.1 However sickle cell crisis can occur if the patient is exposed to hypoxic conditions, high altitude and intense physical exercise.1 Acute events include vaso-occlusive crises such as papillary necrosis of the kidney, ischemic stroke and infections.2

A 59-year-old Caucasian woman presented with dark-red urine and colicky pain in the left flank. She had no fever, dysuria, urinary urgency and no history of trauma, nephrolithiasis or additional episodes of hematuria. She was of Asian ascendancy and had non-consanguineous parents. Her medical history was unremarkable, except for hypertension. Her chronic medication consisted of candesartan/hydrochlorothiazide and she denied non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs use.

Physical examination revealed modest overweight, blood pressure of 110/60mmHg, no evidence of hepatosplenomegaly, although left costovertebral tenderness was noted.

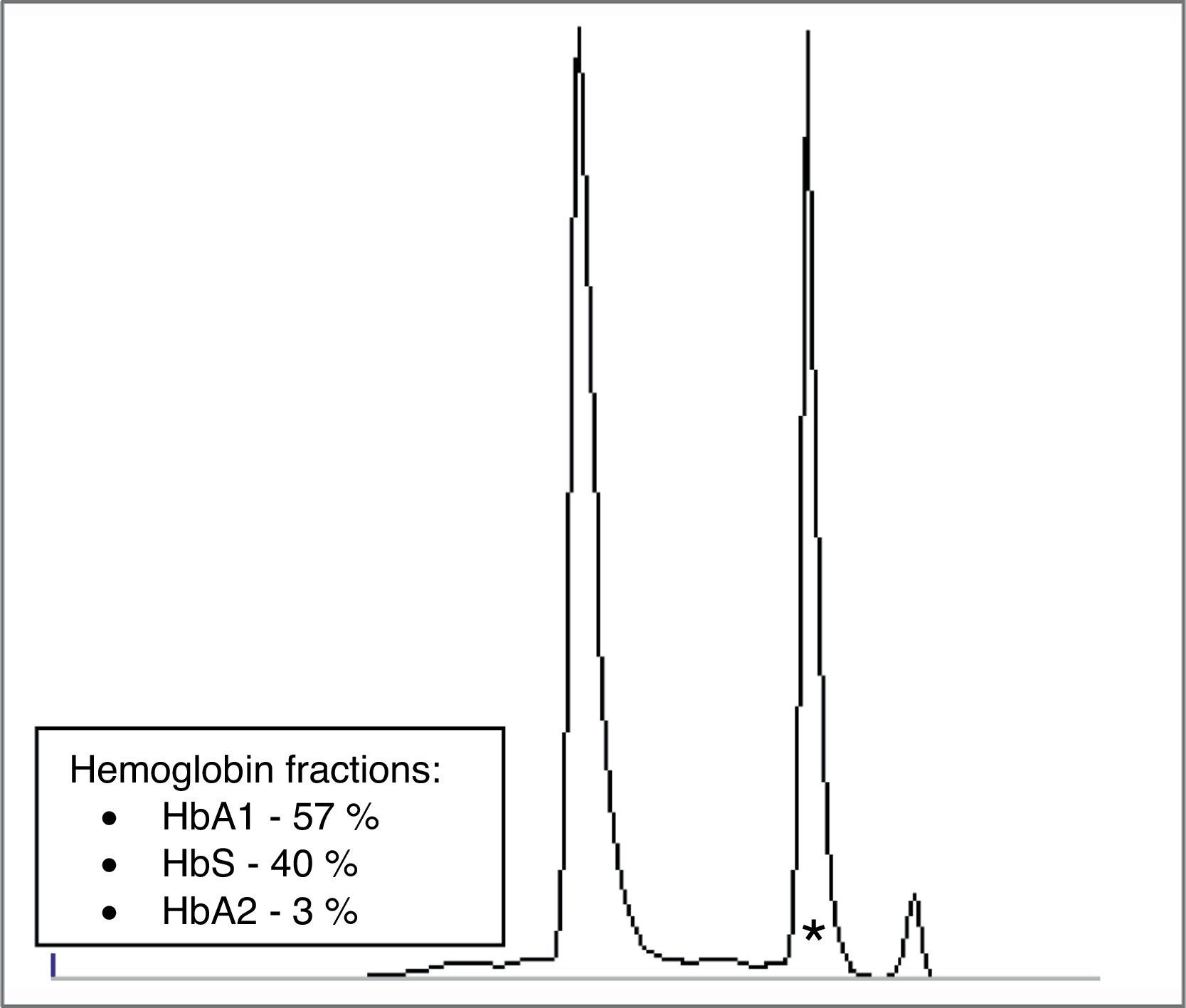

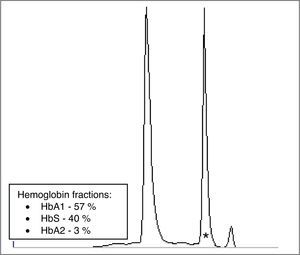

Laboratory tests showed normal blood cell counts, coagulation parameters, electrolytes, and renal and hepatic tests. No rhabdomyolysis nor hemolysis were present. Urine dipstick revealed a specific gravity of 1.010, 3+ hemoglobin and no protein; the microscopic exam showed 168 red blood cells per high power field, but no casts or white blood cells. Urine cultures, including for mycobacteria, were negative. She had no anomalous cells in cytology and a normal cystoscopy. A computed tomography scan (Fig. 1A–C) suggested renal papillary necrosis and excluded other abnormalities. There were no criteria for diabetes mellitus. Hemoglobin's electrophoresis showed the presence of an abnormal hemoglobin (Fig. 2) which was subsequently documented to be HbS. A molecular study revealed an heterozygosity for the hemoglobin sickle mutation of the β-globin gene (HBB:c.20A>T) establishing a diagnosis of SCT.

A, B, C: Sagital, coronal and axial sections of abdominal computed tomography revealing structural heterogeneity of the left renal parenquima with diminished enhancement at the tip of the medullary pyramid and the presence of small cavities filled by contrast on the borders of the small calices – aspects highly suggestive of papillary necrosis ischemia.

Clinical findings resolved after conservative therapy with rest, hydration and analgesia. The patient was recommended to avoid circumstances that may precipitate vaso-occlusive crises. Her daughter was referred for genetic testing.

SCT is generally asymptomatic, although occasionally associated with significant morbidity, including papillary necrosis.1 It is a highly prevalent recessive illness, mainly found in African but also in Asian populations.3 In SCT patients, HbS is abnormally found with plasma concentrations typically between 35% and 45% of total hemoglobin.4

Hematuria is the most common complication1 of SCT, but the usual etiologies, such as stones, urinary tract infections or neoplasms should be considered first. Hence, initial testing must include urine analysis, culture, cytology and imaging studies. In SCT patients, occlusion of small vessels by sickled blood cells, causes microthrombi and ischaemia.2 In the kidneys, this obstruction is predominantly apparent in the renal papilla due to their marginal blood supply. Papillary necrosis can be difficult to diagnose. The presence of sloughed papillae in the urine examination is diagnostic, but has low sensitivity.5 In our patient an ultrasound and a tomography scan allowed the diagnosis. Treatment is usually conservative, but adjuvant therapies (desmopressin or epsilon-amino caproic acid) can be of benefit.1 Most severe cases may require arterial embolization or surgical exploration. The outcome is generally good but the patient must be informed about avoidable precipitating conditions and genetic counseling.2

Hemoglobin's electrophoresis should be part of the diagnostic work-up of renal colic and/or hematuria, namely in patients whose etiology has never been established.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest related to the contents of this article.