The incidence of acute kidney failure in patients with respiratory distress syndrome caused by coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) ranges from 8% to 17% of hospitalised patients according to the different international series, rises to 14%–35% in critical patients and is associated with increased mortality.1 In the series of kidney biopsies performed in patients with COVID 19-associated acute kidney failure, the most frequent diagnosis was acute tubular necrosis.2,3

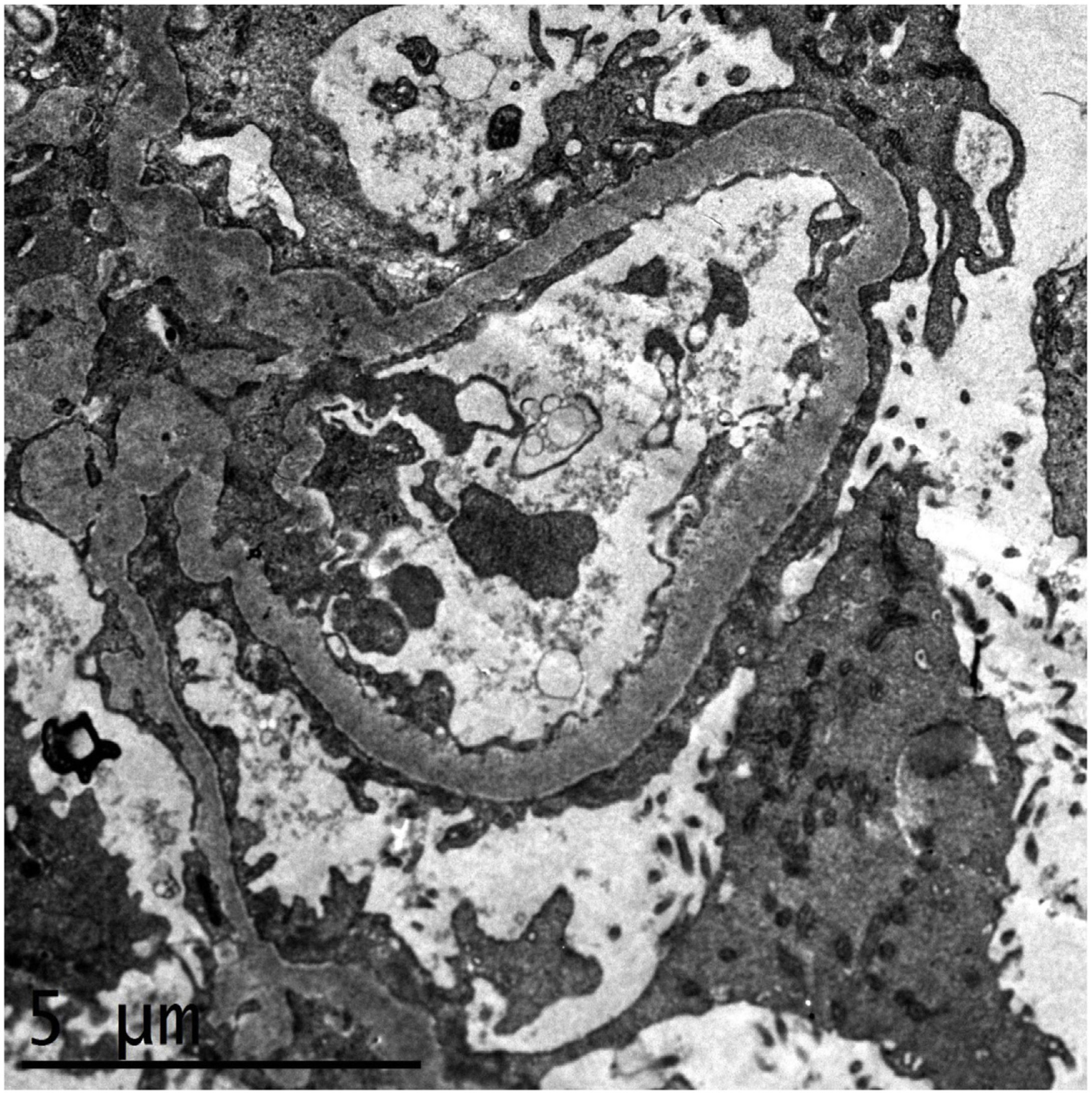

We present the case of a 52-year-old woman from the Dominican Republic, with no medical background of interest nor of taking nephrotoxic medication or substances who came to the Emergency Department (ED) with symptoms of progressive dyspnoea, rhinorrhoea and oedema coursing for three days. On arrival at the ED, she presented severe hypoxaemia and tachypnoea of 40rpm, requiring oxygen therapy with reservoir. A chest radiography showed the presence of bilateral pulmonary infiltrates and a nasopharyngeal exudate sample tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 by PCR. The analysis highlighted a thrombocytosis of 1.4 million platelets/μL, leucocytosis with lymphopenia, serum creatinine of 2mg/dL, microcytic anaemia of 9g/dL, hypoalbuminaemia and marked elevation of acute-phase reactants, proteinuria in the nephrotic range (4g/L) and mild microhaematuria. The peripheral blood smear showed platelets with dysplasia with megaloblastic forms. A JAK2, CALR, MPL and BCR/ABL clonal marker study was performed, proving to be negative. The patient presented a rapid leucocytosis and thrombocytosis correction, clearly pointing to a reactive condition. She progressively presented respiratory impairment, requiring admission to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) with orotracheal intubation and invasive mechanical ventilation. She was treated with ceftriaxone, azithromycin, hydroxychloroquine, lopinavir/ritonavir, steroids and prophylactic anticoagulation, with a poor initial evolution, severe hypoxaemia with respiratory acidosis and oliguria and acute kidney failure, requiring continuous venovenous haemodiafiltration. After seven weeks in the ICU, the patient was extubated, she presented a gradual respiratory improvement and was transferred to the Nephrology ward. The patient recovered her renal function gradually and achieved stabilisation with serum creatinine of 1.5–1.7mg/dL, nephrotic proteinuria of up to 5.8g/24h, hypoalbuminaemia of 2.6g/dL, oedemas and severe arterial hypertension. The serological, immunological and electrophoretic studies were normal. A kidney biopsy was performed, with a diagnosis of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, NOS category, according to the Columbia classification, as well as changes consistent with regenerative-phase acute tubular necrosis. The immunohistochemistry study for CoV-2 was negative. The electronic microscopy identified diffuse foot process fusion affecting more than 80% of the capillary surface, together with images of podocyte microvillus transformation (Fig. 1). No viral inclusions were found. Subsequently, and parallel to the respiratory improvement and in inflammatory markers, the patient presented a gradual remission in proteinuria to 0.4g/24h, with full remission of the nephrotic syndrome at discharge.

Electronic microscopy study showing diffuse foot process fusion affecting more than 80% of the capillary surface, together with images of podocyte microvillus transformation. The basement membranes present their usual thickness and no parietal or mesangial deposits are observed. The endothelial cells present no alterations.

Several viral infections are known to possibly cause different glomerular diseases. HIV, CMV, EBV or B-19 parvovirus may induce focal segmental glomerulosclerosis by producing podocyte involvement, either through direct infection or through the release of inflammatory cytokines that bind to the podocyte receptors.4 There have been recent reports of some cases of acute kidney failure associated with COVID-19 with a diagnosis of collapsing focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, two of them with a kidney transplantation.5–10 All the patients were black and most of them were carriers of risk variants of the APOL1 gene. All the cases initially required kidney replacement therapy, and less than half of the patients presented partial recovery of renal function with persistence of severe proteinuria. Two patients were given high doses of steroids, one remained on haemodialysis and the other achieved partial kidney function recovery and a partial improvement in proteinuria. In the two kidney graft patients, the treatment with mycophenolate was suspended provisionally and the tacrolimus and steroids were maintained, leading to graft loss in one case and the persistence of advanced kidney disease in the other.8,10

The exact mechanism through which COVID-19-associated glomerulopathy occurs is still unknown, although the histopathology of some patients has shown the presence of viral particles in podocyte cytoplasm, which could indicate that it is due to a direct viral invasion of the podocyte.3 Moreover, the possibility of the cytokine release syndrome in COVID-19 patients giving rise to an inflammation-induced podocyte lesion cannot be ruled out.

In conclusion, COVID-19-associated glomerulopathy has emerged as a specific entity associated with SARS-COV-2 infection with a preference for black patients and carriers of APOL1 risk variants, presenting an aggressive course with poor renal prognosis. In our case, the patient recovered renal function and the kidney replacement therapy was discontinued, which is the first case of complete remission of nephrotic syndrome following recovery from COVID 19-induced inflammatory syndrome.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.