Patient activation is a concept that refers to the willingness to manage one's health and medical care. To assess it, a patient activation measure (PAM) has been developed and validated. Several studies report low activation in patients with chronic diseases. However, information on activation in hemodialysis patients is scarce. The aim of the present study is to describe the activation level of patients on chronic treatment in an HD unit and its relationship with disease control parameters.

Materials and methodsCross-sectional observational study in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease on chronic HD treatment. Ninety-six patients were included. Activation was measured with the PAM-13 questionnaire. Its relationship with descriptive variables (age, sex, comorbidity, studies, habitat) and disease control variables (vascular access, blood flow, potassaemia, phosphataemia, interdialytic gain) was studied. For this purpose, Spearman's correlation test, multiple linear regression model and logistic model were used as statistical methods.

ResultsThe mean (SD) PAM-13 score was 63.19 (15.21). Activation was significantly associated with vascular access (P = 0.003), blood flow (P = 0.024), and interdialytic gain of patients (P = 0.008).

ConclusionsActivation in patients on chronic hemodialysis treatment is low. Higher activation is related having an arteriovenous fistula, higher blood flow and lower interdialytic gain. Future studies are needed to confirm and apply our results.

La activación del paciente es un concepto que se refiere a la voluntad de gestionar su salud y atención médica. Para evaluarla, se ha desarrollado y validado una medida de activación del paciente (PAM). Diversos estudios informan baja activación en pacientes con enfermedades crónicas. No obstante, la información sobre activación de pacientes en tratamiento con hemodiálisis es escasa. El objetivo del presente estudio es describir el nivel de activación de pacientes en tratamiento crónico de una unidad de HD y su relación con los parámetros de control de la enfermedad.

Materiales y métodosEstudio observacional transversal en pacientes con enfermedad renal crónica avanzada en tratamiento crónico con HD. Se incluyeron 96 pacientes. La activación se midió con el cuestionario PAM-13. Se estudió su relación con variables descriptivas (edad, sexo, comorbilidad, estudios, hábitat) y variables de control de la enfermedad (acceso vascular, flujo sangre, potasemia, fosfatemia, ganancia interdialítica). Para ello se emplearon como métodos estadísticos la prueba de correlación de Spearman, modelo de regresión lineal múltiple y modelo logístico.

ResultadosLa puntuación media (SD) de PAM-13 fue 63.19 (15.21). La activación se asociaba significativamente con el acceso vascular (P = 0.003), flujo de sangre (P = 0.024), y ganancia interdialítica de los pacientes (P = 0.008).

ConclusionesLa activación de pacientes en tratamiento crónico con hemodiálisis es baja. Una mayor activación se relaciona con disponer de fístula arteriovenosa, con mayor flujo sanguíneo y con menor ganancia interdialítica. Son necesarios futuros estudios que confirmen y apliquen nuestros resultados.

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a serious health problem that affects approximately 10% of the Spanish population.1 In advanced stages it requires follow-up by nephrology specialists and, in some cases, renal replacement therapy (RRT). The prevalence of patients with RRT in Spain is 1362.8 per million, of whom 40.4% are on hemodialysis (HD). This figure indicates the importance of research in this field. In addition, the annual mortality of patients on chronic HD treatment is over 14%, which makes it even more necessary to study factors that may improve these results.2

Activation is a concept that refers to patients' willingness and readiness to take independent action to manage their health and care. To assess patient activation, Hibbard et al. developed the Patient Activation Measure (PAM), an instrument that evaluates the patient's knowledge, skills and confidence in self-management of their health condition.3 The initial questionnaire contained 22 questions, it was later validated and simplified into 13 questions (PAM-13).2,4,5 The Spanish adaptation of the PAM-13 allows it to be used as an equivalent, valid and reliable instrument to assess activation in patients with chronic diseases in Spain.6

In general, the most active patients with chronic diseases follow preventive health measures, avoid bad habits, comply with dietary recommendations, do exercise, adhere to treatment and perform self-monitoring at home. These patients have better indices of glycosylated hemoglobin, blood pressure or cholesterol levels and lower hospitalization or emergency room costs.7,8

By contrast, less activated patients are more likely to hinder their medical care, affecting their health. Low activation is related to age, loneliness, self-perception of health, non-participation in leisure activities, depression, stress, side effects and poor health culture.8,9

Recent studies in patients with CKD have found that activation is low, especially in those receiving HD.10–12 In addition, low activation is also related to older age and diabetes,13 both of which are common in patients on chronic HD.2

However, although activation is a concept widely studied in other populations, and in more recent years is being evaluated in patients with CKD, there is still an important information gap about activation and its consequences in patients on HD treatment.

The present study will describe the activation level of patients on chronic HD and the relationship with control of disease parameters.

MethodsCross-sectional observational study in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease in chronic HD treatment with conducted between January 2020 and February 2021. All patients included were over 18 years of age and signed informed consent. Patients under the age of 18 years, those with cognitive impairment that prevented them from understanding and answering the questionnaires and those who did not give informed consent were excluded.

The descriptive variables were sex (male/female), age (years), comorbidity (Charlson index),14 diabetes mellitus (yes/no), educational level (no education, primary, secondary, post-secondary), habitat (rural, urban) and time on hemodialysis treatment (years). We assessed activation level using the PAM-13 questionnaire5 licensed by Insignia Health LLC, administered by a nurse trained for this purpose. The questionnaire consists of 13 items, described in Table 1, which generates a score on a scale from 0 to 100 points. PAM-13 allows classification into four levels of activation, with level 1 being the least activated and level 4 the most activated. Patients with level 1 believe that their role in disease control is important (score 0–47) those with level 2 have the confidence and knowledge to take action (score 47.1–55.1), those with level 3 take action to maintain and improve health (score 55.2–67) and those with level 4 can maintain those actions even under stress (score 67.1–100).4

PAM-13 Scale adapted to Spanish.

| Item | |

|---|---|

| 1 | Al fin y al cabo, yo soy el/la responsable de cuidar de mi salud. |

| 2 | Desarrollar un papel activo en el cuidado de mi propia salud es lo que más beneficia a mi salud. |

| 3 | Estoy convencido/a de que puedo contribuir a prevenir o reducir problemas relacionados con mi salud. |

| 4 | Sé para qué sirven cada uno de los medicamentos que tengo recetados. |

| 5 | Me siento capaz de reconocer cuándo debo ir al médico o cuándo puedo solucionar un problema de salud por mí mismo/a. |

| 6 | Estoy convencido/a de que puedo explicar mis dudas o preocupaciones al médico, incluso cuando no me pregunta. |

| 7 | Estoy convencido/a de que puedo seguir en casa los tratamientos indicados. |

| 8 | Entiendo mis problemas de salud y sus causas. |

| 9 | Conozco las diferentes opciones de tratamiento para mis problemas de salud. |

| 10 | He sido capaz de mantener cambios en mi estilo de vida, como comer sano o hacer ejercicio. |

| 11 | Sé cómo prevenir problemas relacionados con mi salud. |

| 12 | Estoy convencido/a de que puedo encontrar soluciones cuando surjan nuevos problemas relacionados con mi salud. |

| 13 | Estoy convencido/a de que puedo mantener cambios en mi estilo de vida, como comer sano o realizar ejercicio, incluso durante épocas de estrés. |

As disease control variables, we measured the mean levels of serum phosphorus (mg/dL), serum potassium (mEq/L), serum hemoglobin (g/dL), parathyroid hormone (PTH), calcium (mg/dL) and albumin (g/dL) during the study period. These determinations were obtained monthly in routine HD analytical monitoring. Blood pressure (mmHg) at HD connection, estimated interdialytic weight gain (kg) due to excess weight before each session, interdialytic weight gain relative to dry weight established in the HD regimen (interdialytic weight gain/dry weight), mean dry weight for the period (kg), percentage of final dry weight over baseline [(final dry weight/baseline dry weight) × 100] and body mass index (BMI) (kg/m2) were also recorded. On the other hand, the type of vascular access (central venous catheter (CVC) or arteriovenous fistula (AVF)), blood flow (mL/min), HD session duration (minutes) and dialysis dose (Kt/V and Kt) determined in each session by dialysance in FRESENIUS 5008 monitor.

Data sources were electronic medical records, hemodialysis history in Nefrolink software Renal Information System version 4.5.2018.6 (Nephrocare e-services, Spain) and patient interview.

Regarding biases in the assessement of variables, we assume that the levels of potassemia, phosphatemia and interdialytic weight gain can vary over periods of a few days. To control for this variability, we used the mean of the entire period (January 2020 to February 2021). To avoid the potential for patients to feel coerced by their physicians, nursing staff administered the PAM-13 questionnaire.

The variables studied are presented as mean, standard deviation, median and first and third quartiles in the case of continuous variables and as relative and absolute frequencies in the case of categorical variables, in order to visualize their distribution and look for possible sources of error if outliers are present.

Regarding statistical methods, in a first approximation we carried out a univariate analysis to evaluate activation as an independent variable and its relationship with disease control parameters. Spearman's correlation test was used for continuous variables and Student's t-test for categorical variables. The sign of the coefficient indicates the direction of the association; if it is positive it indicates direct correlation, in which both variables increase or decrease in the same direction, and if it is negative it indicates inverse correlation in which one variable increases while the other decreases. In addition, the value of the coefficient indicates the intensity of the association between the two variables, the key point being that the association will be stronger as it moves away from 0. Thus, values of −1 or 1 indicate a perfect, inverse or direct correlation, respectively. There are different scales to interpret the correlation coefficient, according to the range scale, it would be scarce or null (0−0.25), weak (0.26−0.50), between moderate and strong (0.51−0.75) and between strong and perfect (0.76–1).15 Another scale indicates a coefficient of 0 null association, 0.1 small association, 0.3 medium, 0.5 moderate, 0.7 high and 0.9 very high association. It is completed with a hypothesis test with the null hypothesis of no correlation, so that if the difference is statistically significant, correlation is assumed to exist.16

Once the first statistical analyses had been performed and the results evaluated, we proposed a multivariate analysis that took into account the descriptive variables of the study. A multiple linear regression model was used to study the relationship of the activation level in quantitative form (score from 1 to 100) with the continuous variables and a logistic model with vascular access, which is a dichotomous variable.

Both the preliminary analysis of the variables and the statistical study were carried out mainly using relevant packages in the "R" language, version 4.2.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

ResultsDuring the study period, 151 chronic patients underwent dialysis in the unit and 96 met the criteria and were included in the study. The characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 2.

Sample characteristics of the patient population.

| n 96Mean (SD) or frequency (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 72.52 (11.53) |

| Sex, female | 45 (46.87%) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 46 (47.92%) |

| Charlson Index | 7.56 (2.23) |

| Level of education | |

| None | 35 (39%) |

| Primary. | 40 (44%) |

| Secondary | 7 (8%) |

| Post-secondary | 8 (9%) |

| Unknown | 6 |

| Habitat | |

| Rural | 72 (81%) |

| Urban | 17 (19%) |

| Unknown | 7 |

| Time in HD treatment (years) | 6.34 (6.72) |

| Vascular access, arteriovenous fistula | 69 (71.87%) |

| Blood flow (mL/min) | 357.19 (35.83) |

| HD session duration (minutes) | 220.49 (24.09) |

| Kt/V | 1.73 (0.27) |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 142.08 (18.39) |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 62.76 (10.44) |

| Interdialytic weight gain (kg) | 1.83 (0.75) |

| Dry weight (kg) | 72.66 (16.20) |

| Interdialytic weight gain relative to dry weight | 0.03 (0.01) |

| Final dry weight/basal (%) | 98.55 (5.82) |

| Body Mass Index (BMI) (kg/m)2 | 27.90 (6.24) |

| Serum phosphorus (mg/dL) | 4.26 (1.08) |

| Serum potassium (mEq/L) | 4.87 (0.51) |

| Serum hemoglobin (g/dL) | 11.54 (0.63) |

| Parathyroid hormone (pg/mL) | 206.98 (114.46) |

| Serum calcium (mg/dL) | 8.98 (0.46) |

| Serum albumin (g/dL) | 3.85 (0.33) |

HD, hemodialysis; SD, standard deviation; NS/NC, don't know, no answer.

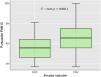

The 96 patients completed the PAM-13 survey: the mean (SD) PAM-13 score was 63.19 (15.21) and its distribution is shown in Fig. 1. The distribution of PAM-13 was 17% (n = 16), 11% (n = 11), 47% (n = 45) and 25% (n = 24), in levels 1–4, respectively (Fig. 2).

No significant associations were observed between the level of activation and the descriptive characteristics of the patients (sex, age, comorbidity, diabetes mellitus, education, habitat and time on hemodialysis treatment).

A correlation analysis of activation with the study parameters was performed and the results are shown in Table 3.

Correlation analysis of PAM-13 score with study variables.

| Spearman's correlation coefficient (ρ) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|

| Blood flow (mL/min) | 0.22 | 0.03* |

| HD session duration (minutes) | 0.00 | 0.98 |

| Kt/V | −0.12 | 0.25 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 0.18 | 0.08 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 0.07 | 0.53 |

| Interdialytic weight gain relative to the dry weight | −0.30 | <0.01** |

| Dry weight (kg) | 0.12 | 0.2 |

| Final dry weight/basal (%) | −0.013 | 0.90 |

| Body mass index (kg/m)2 | 0.10 | 0.33 |

| Serum phosphorus (mg/dL) | 0.04 | 0.73 |

| Serum potassium (mEq/L) | −0.11 | 0.29 |

| Serum hemoglobin (g/dL) | 0.06 | 0.56 |

| Parathyroid hormone (pg/mL) | −0.03 | 0.80 |

| Serum calcium (mg/dL) | −0.08 | 0.43 |

| Serum albumin (g/dL) | −0.10 | 0.32 |

HD: hemodialysis.

The above results show significant correlation of activation with blood flow and with interdialytic weight gain relative to dry weight. The degree of association between these target variables and activation, following the previously described scales, will be for blood flow a weak or small direct correlation, the higher the activation the higher the blood flow, while for interdialytic weight gain relative to dry weight it is a weak or medium inverse correlation, indicating that a higher activation score is associated with lower values of weight gain. In addition, we analyzed whether there is a significant difference in the distribution of activation with respect to the type of vascular access, using Student's t-test. The distributions as well as the p-value resulting from the test are in Fig. 3:

The boxplots in Fig. 3 illustrate the distribution of the activation score for a CVC type vascular access (with median x˜ = 55.6 and standard deviation σ = 12.3) and for AVF type vascular access (x˜ = 66.1 and σ = 15.4). The result of applying a t-test to these groups is a value of t = 3.424 with a p-value = 0.0011, so that, taking into account a significance level of α = 0.05, we can confirm the existence of significant differences between the two groups. Therefore, patients with AVF vascular access presented higher activation levels than those with CVC.

Multivariate modeling was performed for each target variable to study whether or not there is a significant relationship with respect to the activation variable (PAM-13 score). The models are constructed with various target variables as the dependent variable and activation as the explanatory variable, in the presence of several descriptive variables (sex, age, comorbidity by Charlson Index, diabetes mellitus and time on HD treatment).

The results are presented in Table 4, which contains the values of the odds ratio (estimator), interquartile range and p-value obtained for activation in the model for each target variable.

Multivariate analysis of study parameters vs. activation.

| Target variable | Estimator | IC Range | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vascular access** | 0.934 | 0.888; 0.973 | 0.003* |

| Blood flow (mL/min) | 0.538 | 0.080; 0.997 | 0.024* |

| HD session duration (minutes) | 0.15 | −0.174; 0.474 | 0.367 |

| Kt/V | −0.001 | −0.004; 0.002 | 0.448 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 0.193 | −0.044; 0.429 | 0.114 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 0.04 | −0.079; 0.158 | 0.515 |

| Interdialytic weight gain on dry weight | 1.730−10−4 | 3−10−4; −5−10−5 | 0.008* |

| Dry weight (kg) | 0.14 | −0.072; 0.352 | 0.200 |

| Final dry weight/basal (%) | 0.04 | −0.037; 0.116 | 0.309 |

| Body mass index (kg/m)2 | 0.032 | −0.048; 0.111 | 0.435 |

| Serum phosphorus (mg/dL) | 0.004 | −0.01; 0.018 | 0.573 |

| Serum potassium (mEq/L) | −0.003 | −0.01; 0.003 | 0.324 |

| Serum hemoglobin (g/dL) | 0.003 | −0.006; 0.011 | 0.540 |

| Parathyroid hormone (pg/mL) | −0.193 | −1.692; 1.306 | 0.801 |

| Serum calcium (mg/dL) | −0.001 | −0.007; 0.005 | 0.843 |

| Serum albumin (g/dL) | −0.002 | −0.006; 0.002 | 0.352 |

HD, hemodialysis; CI, confidence interval.

The results obtained indicate a significant relationship of the variables vascular access, blood flow and interdialytic dry weight gain with patient activation, in the presence of the explanatory variables in the model. Specifically, higher activation levels are associated with higher blood flow and lower interdialytic dry weight gain. As for vascular access, the estimator obtained after logistic modeling is the odds ratio, with a value of 0.934. This value indicates that the probability of a patient having AVF vascular access with respect to the probability of it being CVC increases 0.934 for each unit that activation increases. In other words, the higher the level of activation, the greater the probability (0.934) of the vascular access being fistula type rather than catheter.

Interdialytic weight gain relative to dry weight correlated negatively with patient activation, so that more activated patients had lower interdialytic weight gain (Fig. 4).

Fig. 5 shows the relationship between vascular access blood flow and activation score: more activated patients have better blood flow.

DiscussionThe results of the present study show low activation scores of patients on chronic HD treatment. More than a quarterof patients show low levels of activation (levels 1 and 2). These results were lower than those observed in the general adult population.17 Moreover, activation level was inversely associated with interdialytic weight gain, type of vascular access and blood flow.

Activation in chronic patients is generally low due to their condition. Several studies from other countries report that the mean activation score for patients with chronic disease ranges between 57 and 65.5,11,18 There are recent findings on activation in patients with chronic kidney disease and specifically in patients on HD treatment. The mean activation scores observedin patients on chronic HD in the UK,19 USA12 and Korea20 were similar (55.1, 56 and 59.5, respectively). Our results (63.2) are higher than in these countries but similar to those obtained in populations with chronic diseasefrom other cities within Spain.6

There are few studies of the association between activation and CKD-related parameters. There are studies on associations of activation with BMI,21 glomerular filtration rate, hemoglobin levels and cardiorespiratory fitness.19 However, we are unaware of studies describing the relationship of activation with vascular access and with patient interdialytic weight gain, so our finding is novel in a field with many unknowns.

Patients on HD change their hydration status between sessions. Interdialytic weight gain in HD leads to difficulties in adjusting the patient's dry weight and long-term cardiovascular complications that may affect survival.22 Our study indicates that more activated patients had lower interdialytic dry weight gain, which may be related to greater willingness to comply with dietary restrictions, more self-care and greater awareness of their disease. Recently, Flythe et al.23 in their conclusions to a lecture on controversies in renal disease recommended interventions to activate the patient as a way to improve adherence to dietary restrictions, and encouraged the evaluation of such interventions. Our finding supports the possibility of designing patient activation intervention strategies aimed at improving control of interdialytic weight gain.

It is well documented that arteriovenous fistula generally presents better performance and lower rate of infections, in addition to better survival of patients with this form of vascular access.24,25 Our study reports for the first time that patients with AVF are more activated than those with CVC and the more activated patients have better blood flow. It is possible that better activation, including willingness to follow medical recommendations, stimulates the patient to provide greater care and vigilance of his or her AVF, which could lead to greater survival of this vascular access. In the present study, we did not observe associations of activation or vascular access with other sociodemographic factors; however, the relationship between activation and vascular access should be verified and analyzed in greater depth in future studies, considering all possible influencing factors. If this relationship is confirmed, it opens up potential interventions for activation that could increase the survival of AVF and improve their performance. It should be remembered that the waiting time for AVF each health center may have an important influence on its prevalence. In our center, the waiting time from the request for the procedure ranges from two to four weeks, so we would should not expect interference; however, these times may be different in other centers and could modify the effect of activation on vascular access.

Our study has limitations. The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic coincided with the study period. This health alert situation could have influenced the results of the activation measurement. Another limitation could have been difficulty understanding the questions. To control for this, we avoided self-administration of the questionnaire, instead administering it with the support of a trained nurse. The possibility of patients answering to please their physician was also avoided by administration by nurses. Even so, it is possible that some of these deviations may have influenced the results. We averaged the duration of session and blood flow over the course of the study, rather than using any given day's results, to avoid any possible influence from other staff. Likewise, we repeated this method to avoid the effect of the possible modification of the patient's diet on the dates close to the administration of the questionnaire.

In conclusion, activation is low in patients on chronic hemodialysis. Greater activation is related to having an arteriovenous fistula, greater blood flow and lower interdialytic weight gain. The present findings could have an influence on the patient's vital prognosis. Future studies are required to confirm these results, assess their influence on patient survival and initiate the search for new interventions on activation to improve outcomes of patients with chronic kidney disease on HD treatment.

FinancingThis work has not received any funding.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

We thank the patients for their participation in the study.