The European Renal Association and the European Dialysis and Transplant Association (ERA-EDTA) have issued an English-language new coding system for primary kidney disease (PKD) aimed at solving the problems that were identified in the list of “Primary renal diagnoses” that has been in use for over 40 years.

PurposeIn the context of Registro Español de Enfermos Renales (Spanish Registry of Renal Patients [REER]), the need for a translation and adaptation of terms, definitions and notes for the new ERA-EDTA codes was perceived in order to help those who have Spanish as their working language when using such codes.

MethodsBilingual nephrologists contributed a professional translation and were involved in a terminological adaptation process, which included a number of phases to contrast translation outputs. Codes, paragraphs, definitions and diagnostic criteria were reviewed and agreements and disagreements aroused for each term were labelled. Finally, the version that was accepted by a majority of reviewers was agreed.

ResultsA wide agreement was reached in the first review phase, with only 5 points of discrepancy remaining, which were agreed on in the final phase.

ConclusionsTranslation and adaptation into Spanish represent an improvement that will help to introduce and use the new coding system for PKD, as it can help reducing the time devoted to coding and also the period of adaptation of health workers to the new codes.

La European Renal Association-European Dialysis and Transplant Association (ERA-EDTA) ha publicado, en lengua inglesa, una nueva lista de códigos de enfermedad renal primaria (ERP), con el fin de solventar los problemas detectados en la «Lista de diagnóstico renal primario» que se venía utilizando desde hacía más de 40 años.

ObjetivosEn el seno del Registro Español de Enfermos Renales (REER) se consideró conveniente traducir y adaptar los términos, definiciones y notas de los nuevos códigos de la ERA-EDTA para facilitar su uso por parte de quienes usan como lengua de trabajo el español.

MétodosSe realizó un proceso de traducción profesional y adaptación terminológica que contó con la participación de nefrólogos bilingües con varias fases de contraste del resultado de la traducción, en las que se revisaron los códigos, literales, definiciones y criterios diagnósticos y se marcaron los acuerdos y discrepancias surgidos para cada término. Finalmente se acordó la versión aceptada por la mayoría de los revisores.

ResultadosEl acuerdo en la primera fase de revisión fue amplio, con solo 5 puntos de discrepancia que se acordaron en la fase final.

ConclusionesLa traducción y adaptación al español representa una mejora para la introducción y uso del nuevo sistema de codificación de ERP, ya que puede contribuir a reducir el tiempo dedicado a la codificación y también el período de adaptación de los profesionales a los nuevos códigos.

Disease coding for international use has a long history, and its beginnings date from 1893.1 Since then, various coding systems have been developed for cause of death, diseases, processes, and clinical acts. The most extensively used is the group of international classifications2 endorsed by the World Health Organisation, the most notable is the International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD). One of the main reasons of using this type of classification is to be able to compare the status of various diseases both nationally and internationally.

In the field of renal disease, the European Dialysis and Transplant Association (EDTA), at the beginning of its registry activities3 in 1963, published a list of diagnoses, which was named “primary renal diagnosis (PRD) list”, which served as a guideline when making a diagnosis of primary kidney disease (PKD). After several years of use, and being supported since 1983 by the European Renal Association (ERA) and the EDTA, by means of the ERA-EDTA registry, this PRD list, which was subsequently expanded and modified, turned into a commonly used standard in renal disease registries, for coding of PKD. However, the presence of gaps in the PRD list often caused frustration among the users, because they had to adapt to a system that did not offer adequate coding options and had a limited guarantee of quality and data validation, as the precision of the coding was not guaranteed. After more than 40 years of use, the ERA-EDTA Registry Committee identified its problems, recognising4 that the terms in the PRD list were incomplete and inflexible; the list lacked definitions, the term “other/s” was used without a defined criteria, there were no users guidelines, its application was inconsistent both nationally and internationally, it was not possible to indicate how accurate was the code used, and there were no formal mechanisms to add or remove codes. Also, the list had been developed in an era before the use of computers, so it was not adapted for use in that context. Furthermore, the codes did not have correspondence with other classification systems–such as ICD or SNOMED-CT (Systematised Nomenclature of Medicine-Clinical Terms)5–which made interoperability between registries very difficult, and limited the possibility of such data being used for epidemiological studies or other additional uses.

It was in these circumstances that the ERA-EDTA expressed the interest in developing and publishing a new PRD code list4 that would be adjusted to international standards so the use and reliability would be increased, just as been proposed by those renal patient registries that were consulted.

For this reason, as part of the European Nephrology Quality Improvement Network Initiative,6 a European Registries Coding and Definitions Working Group (RCDWG) was created, which included nephrologists, epidemiologists, computer technicians, and coding specialists. This group began its activities between 2005 and 2006, aiming “to improve and standardise the terminology of definitions and coding used in European renal registries to describe primary renal diagnoses”. In 2012, the new PKD7 coding list was published in English, and was distributed to the various registries affiliated to the ERA-EDTA. At the same time, access was given to a coding help tool (“ERA-EDTA coding system for primary kidney disease [PKD] and the related PKD search tool”).

The link between the new PKD codes of the ERA-EDTA and other classification systems, such as ICD and SNOMED-CT, offers some advantages. One of the most obvious advantage is the validation of terms being translated into languages other than English. However, those translations are valid only for the terms and not for the definitions or other aspects included in the system.

For this reason, the various registries included in the Registro Español de Enfermos Renales (REER) (Spanish Register of Renal Patients), considered that it was advisable to proceed to the translation and adaptation of terms and definitions and clarifications of the new PKD codes of the ERA-EDTA. This would be useful for renal patient registries that use Spanish as a working language, not only in Spain, but in other countries.

The aim of this project is to present the results of the translation and adaptation process into Spanish of the new ERA-EDTA PKD codes.

MethodsThe starting point for the translation was the list of PKD codes included in the new ERA-EDTA coding system, which comprises 271 codes.

The codes, definitions, diagnostic criteria, scoring, and correlation with other classification systems (ICD 10th revision, SNOMED-CT, OMIM8 [On-line Mendelian Inheritance in Man]), as well as the “old” ERA-EDTA codification system, were obtained from the ERA-EDTA registry in MS-Excel® spreadsheet format.

Each code has a unique sequence number (“non-semantic identifier”). That number, which has no other significance, allows users to use search tools, and to re-order and select codes. The definitions indicate the type of diagnostic information needed to select a code, including the terms “histológicamente probado” (histologically proven) and “sin histología” (no histology). There is also detailed information on the codes and their characteristics, in a section called “information for users”.

For the adaptation to Spanish of the English-language version, a professional specialised medical translator translated the list of codes and subheadings of PKD, definitions, diagnostic criteria, and scoring. Then, the translation was compared with the original list by a bilingual (Spanish-English) physician not specialised in nephrology. Next, 5 bilingual (Spanish-English) nephrologists compared the translation results with the original list. These specialists reviewed each of the codes, subheadings, definitions, and diagnostic criteria. They could ascribe 3 possible results for each code: (1) total agreement with the translation, (2) disagreement with one of the terms used in the translation, and (3) disagreement with more than one of the aspects of the code translation.

All terms included in category 1 were accepted as valid. When more than 2 of the reviewers marked a translation in category 2 or 3, the revised proposal was accepted. In all cases of discrepancy among the reviewers, either regarding the terms used or the reasons for discrepancy, the terms were sent once again to all reviewers for verification, comments, and final approval.

The process took place between July 2012 and February 2013.

Finally, the version agreed on by the majority of reviewers was accepted, and prepared in an MS-Excel® spreadsheet, the same as the original version.

ResultsFor analysis, the document was divided into the same sheets that completed the MS-Excel® format.

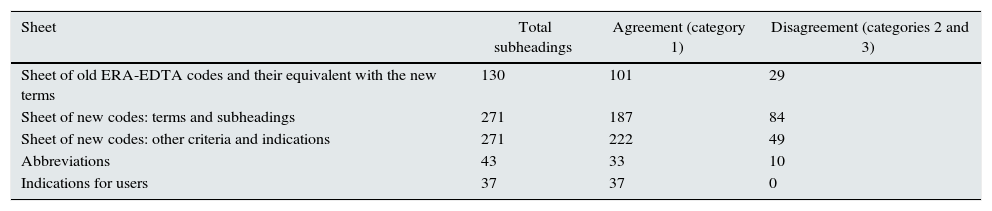

The agreements reached were separated by categories in each sheet as shown in Table 1. In most cases, there was total agreement (category 1).

Results of the agreement reached among nephrology specialists, by agreement category.

| Sheet | Total subheadings | Agreement (category 1) | Disagreement (categories 2 and 3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sheet of old ERA-EDTA codes and their equivalent with the new terms | 130 | 101 | 29 |

| Sheet of new codes: terms and subheadings | 271 | 187 | 84 |

| Sheet of new codes: other criteria and indications | 271 | 222 | 49 |

| Abbreviations | 43 | 33 | 10 |

| Indications for users | 37 | 37 | 0 |

Agreement categories: (1) total agreement with the translation, (2) disagreement with one of the terms used in the translation, and (3) disagreement with more than one aspect of the code translation.

Most of the disagreement scores referred to minor problems, for example:

- •

Use of the term “sordera nerviosa” (Neural deafness) instead of “sordera neurosensorial” (sensorineural deafness) in Alport syndrome.

- •

The term “nefropatía balcánica” (Balkanese nephropathy) instead of “nefropatía de los Balcanes” (Balkan nephropathy).

- •

Use of “síndrome nefrótico infantil - sin pruebas a esteroides - sin histología” (nephrotic syndrome of childhood–no trials of steroids–no histology) instead of “síndrome nefrótico infantil - sin prueba de esteroides - sin histología” (nephrotic syndrome of childhood–no trial of steroids–no histology).

- •

In the case of “poliangitis microscópica - histológicamente probada” (Microscopic polyangiitis–histologically proven) the acronym “PAM” was added.

- •

Use of “fibrosis retroperitoneal secundaria a malignidades” (retroperitoneal fibrosis secondary to malignancies) instead of “fibrosis retroperitoneal secundaria a neoplasias” (retroperitoneal fibrosis secondary to neoplasms).

There were other discrepancies with the translation from the original version concerning more significant changes, for example:

- •

Addition of the term “enfermedad por depósito de cadenas ligeras” (disease due to light chain deposits) in myelomatosis, which was not present in the original English version.

- •

Substitution of the term “IgA secundaria a nefropatía por cirrosis hepática - sin histología” (IgA secondary to nephropathy due to liver cirrhosis–no histology) for “nefropatía IgA secundaria a cirrosis hepática - sin histología” (IgA nephropathy secondary to liver cirrhosis–no histology).

The points of greatest discrepancy were:

- •

Use of the terms “sin histología” (no histology), “sin control histológico” (no histological control”, and “no histológica” (non-histological).

- •

The use of the terms “histológicamente confirmado” (histologically confirmed), “con diagnostic histológico” (with histological diagnosis), and “histológicamente comprobado” (histologically proven).

- •

The term “segmentaria y focal” (segmental focal) vs “focal y segmentaria” (focal segmental).

- •

The name for new code 1504, which in some cases was called “púrpura de Schönlein-Henoch” (Schönlein-Henoch purpura) and in others “púrpura de Henoch-Schönlein” (Henoch-Schönlein purpura).

- •

Use of the terms “ácido úrico” (uric acid) vs “uratos” (urates).

Finally, after all reviews were performed, the biggest discrepancies were agreed as follows:

- 1.

The term “sin histología” (no histology) was accepted.

- 2.

The term “histológicamente probado” (histologically proven) was accepted.

- 3.

The term “focal y segmentaria” (focal segmental) was accepted.

- 4.

The name of the new code 1504 was accepted as “púrpura de Schönlein-Henoch” (Schönlein-Henoch purpura).

- 5.

The term “ácido úrico” (uric acid) was accepted in place of “uratos” (urates).

The list of codes, in their translation into Spanish, can be viewed on the websites of the Registro de Enfermos Renales de la Comunitat Valenciana (Valencian Community Register of Renal Patients) and of the Sociedad Española de Nefrología (SEN) (Spanish Society of Nephrology):

h**ttp:**//ww**w.sp.san.gva.es/Renales/

h**ttp**://ww**w.senefro.org/modules.php?name=webstructure&idwebstructure=128

On one hand, the new ERA-EDTA codes mean abandoning a coding system and PKD registry that is already well-known and has been used for many years, but on the other hand, it means the offer of flexibility and precision in coding, thus increasing the possibilities for use of the data collected.

The introduction of the new codes which is now required by the ERA-EDTA for all European registries, will need a period of adaptation for all those involved in coding. This is due to the change in concepts and longer time needed to select a PKD code.

In Spain, part of this adaptation project has progressed already, as the Spanish Society of Nephrology (SEN) took the initiative to create a diagnosis index for the different renal diseases and reasons for consultation.9 This diagnosis index has been standardised and validated for use in electronic patient notes and is especially focused to outpatient care, where the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) 9th revision is used as the coding system (clinical modification: ICD-9-CM).

The introduction of new coding systems is always a costly process in terms of time and effort, and the choice of the best system is hardly ever free from disagreement, or even controversy.10,11 Furthermore, coding and classification schemes and systems are always affected by the intention to achieve a balance between the having enough detail and the need to be simple and relatively straightforward,12, this fact certainly applies to this new coding system.

It is important to point out that the advantages offered by the new ERA-EDTA codes outweigh the inconveniences. The advantages include the addressing of previous coding gaps, thus improving precision and certainty when using a code for a specific diagnosis according to international standards; there is an increase in semantic interoperability; and there are more potential for epidemiological analysis. The inconveniences of the system are the increase in the number of codes (271 in the new list vs the previous 65), and the fact that the introduction of definitions and diagnostic criteria will make more laborious the process of choosing a code and, the intrinsic adaptation to the whole system change. Furthermore, it will require modification of the computer applications currently used. This last inconvenience could be overcome by new system which offers a link from the new codes to the old ones, therefore the technical adaptation should be relatively fast, and be further facilitated by the ERA-EDTA allowing the use of old codes for a period of time.

Although the link with SNOMED-CT, and other classifications, already allows access to the original version in various languages, in reality, this is indirect access and is of little practical use for those who must do the initial coding. Therefore, the translation and adaptation to Spanish represents an improvement for the introduction and use of the new system. The fact that the help document is available in the working language could help reduce the time dedicated to coding and the adaptation period.

This new coding and classification system does not reflect all possible groupings and breakdowns of diseases, which could also be considered a drawback. However, all classification and coding systems are ultimately the product of some consensus acceptable to the majority and that cannot provide a solution to all possible issues.

The adaptation, performed technically and professionally, and reviewed by clinicians, was carried out in a short time and is the first version of this system in a language other than English. This was also made easier, as planned,4 by the link with the codes previously established and available in Spanish, such as ICD and SNOMED-CT. Furthermore, this adaptation to Spanish will allow more possibilities of collaboration with renal patient registries using Spanish as their working language, which is of particular interest for Latin America.13

However, using a system that has been translated from its original language to another is not without its difficulties, the greatest of which is checking that the translation and review process has not changed the meaning of the codes from one language to the other. In linguistic and transcultural adaptation–above all in the validation of questionnaires – this is usually a process of translation and subsequent back-translation. In this case, however, back translation was not performed for two reasons; firstly, because back-translation does not always preclude subtle differences between two languages14; and secondly, because it was accepted that appropriate adaptation to the medical culture–in this case nephrology–would be assured by the review process carried out by the 5 participating nephrologists. Nonetheless, once this system is implemented in the various PKD coding environments, the results obtained will need to be validated by comparison if its operating, evaluating the intra- and inter-coder coherence. This process has already been implemented in other settings15 and should be done not only at a national but also international level. It will allow us to determine whether the possible variations observed are due to clinical differences, epidemiological differences, or differences in care, or due to the coding system.

In conclusion, the ERA-EDTA has made a PKD coding system that addresses the shortcomings of the previous list and is in line with international standards, available to the nephrology scientific community. Now, this adapted system is available to Spanish-speaking nephrologists in their working language, something that should result in an improvement in its use.

Conflicts of interestNone declared.

Please cite this article as: Zurriaga Ó, López-Briones C, Martín Escobar E, Saracho-Rotaeche R, Moina Eguren Í, Pallardó Mateu L, et al. Adaptación en español del nuevo sistema de codificación de enfermedad renal primaria de la European Renal Association-European Dialysis and Transplant Association (ERA-EDTA). Nefrologia. 2015;35:353–357.