Hepatitis C is an important agent of liver damage in patients with chronic kidney disease and the advent of DAAs has dramatically changed the management of HCV positive patients, including those with advanced CKD. Sofosbuvir is the backbone of many anti-HCV regimens based on DAAs but it remains unclear whether it is appropriate for HCV-infected patients with stage 4–5 CKD.

Study aims and designWe performed a systematic review of the literature with a meta-analysis of clinical studies in order to evaluate the efficacy and safety of SOF-based DAA regimens in patients with stage 4–5 CKD. The primary outcome was sustained viral response (as a measure of efficacy); the secondary outcomes were the frequency of SAEs and drop-outs due to AEs (as measures of tolerability). The random-effects model of DerSimonian and Laird was adopted, with heterogeneity and stratified analyses.

ResultsThirty clinical studies (n=1537 unique patients) were retrieved. The pooled SVR12 and SAEs rate was 0.99 (95% confidence intervals, 0.97; 1.0, I2=99.8%) and 0.09 (95% CI, 0.05; 0.13, I2=84.3%), respectively. The pooled SVR12 rate in studies with high HCV RNA levels at baseline was lower, 0.87 (95% CI, 0.75; 1.0, I2=73.3%) (P<0.001). The pooled drop-out rate due to AEs was 0.02 (95% CI, −0.01; 0.04, I2=16.1%). Common serious adverse events were anemia (n=26, 38%) and reduced eGFR (n=14, 19%). SAEs were more common in studies adopting full-dose sofosbuvir (pooled rate of SAEs 0.15, 95% CI, 0.06; 0.25; I2=80.1%) and in those based on ribavirin (0.15, 95% CI, 0.07; 0.23, I2=95.8%). Six studies (n=69 patients) reported eGFR levels at baseline/post- antiviral therapy; no consistent changes were found.

ConclusionsSOF-based regimens appear safe and effective in patients with stage 4–5 CKD. Serum creatinine should be carefully monitored during therapy with SOF in patients with CKD. Randomized controlled studies in order to expand our knowledge on this point are under way.

La hepatitis C es un importante agente de daño hepático en los pacientes con enfermedad renal crónica. La aparición de los antivíricos de acción directa (AAD) ha cambiado espectacularmente el tratamiento de los pacientes con positividad para el virus de hepatitis C (VHC), incluidos los que presentan enfermedad renal crónica (ERC) avanzada. El sofosbuvir es la piedra angular de muchos tratamientos contra la infección por el VHC basados en AAD, pero sigue habiendo dudas sobre si es apropiado en los pacientes con infección por el VHC y ERC en estadio 4-5.

Objetivos y diseño del estudioRealizamos una revisión sistemática de la literatura médica con un metaanálisis de estudios clínicos para evaluar la eficacia y la seguridad de tratamientos con AAD basados en el sofosbuvir en pacientes con ERC en estadio 4-5. El criterio principal de valoración fue la respuesta virológica sostenida (como indicador de la eficacia); los criterios secundarios de valoración fueron la frecuencia de acontecimientos adversos graves (AAG) y los abandonos por acontecimientos adversos (AA) (como indicadores de la tolerabilidad). Se adoptó el modelo de efectos aleatorios de DerSimonian y Laird, con análisis estratificados y de heterogeneidad.

ResultadosSe recuperaron 30 estudios clínicos (n = 1.537 pacientes individuales). La tasa agrupada de respuesta virológica sostenida a las 12 semanas (RVS12) y de AAG fue de 0,99 (intervalos de confianza del 95%, 0,97; 1,0, I2 = 99,8%) y 0,09 (IC del 95%, 0,05; 0,13, I2= 84,3%), respectivamente. La tasa agrupada de RVS12 en estudios con niveles altos de ARN del VHC al inicio fue menor, 0,87 (IC del 95%, 0,75; 1,0, I2 = 73,3%) (p < 0,001). La tasa agrupada de abandonos por AA fue 0,02 (IC del 95%, –0,01; 0,04, I2 = 16,1%). Los acontecimientos adversos graves frecuentes fueron anemia (n = 26, 38%) y filtración glomerular estimada (FGe) reducida (n = 14, 19%). Los AAG fueron más frecuentes en los estudios que administraron sofosbuvir en la dosis completa (tasa agrupada de AAG 0,15, IC del 95%, 0,06; 0,25; I2 = 80,1%) y en los que se administró ribavirina (0,15, IC del 95%, 0,07; 0,23, I2 = 95,8%). En seis estudios (n = 69 pacientes) se notificaron niveles de FGe al inicio/después del tratamiento antivírico; no se observaron variaciones sistemáticas.

ConclusionesLos tratamientos basados en SOF parecen seguros y eficaces en los pacientes con ERC en estadio 4-5. La creatinina sérica debe vigilarse atentamente durante el tratamiento con SOF en los pacientes con ERC. Se están llevando a cabo estudios controlados aleatorizados para ampliar nuestros conocimientos al respecto.

Hepatitis C virus infection and CKD are important public health issues globally; it has been estimated that around 71 million people are chronically infected with HCV and the frequency of CKD is 10–15% in the adult general population of industrialized countries. The relationship between HCV infection and CKD is complex; some types of kidney disease are precipitated by HCV infection and patients on haemodialysis are at increased risk of acquiring HCV.1 The prevalence rates of HCV in dialysis population range from 3 to 50% within dialysis units of developed or less-developed countries.2

Chronic HCV infection has been associated with both liver disease-related deaths and cardiovascular mortality in HD patients.3 Although there are scarce data demonstrating that the sustained viral response improves survival in CKD, accumulated evidence shows a decreased mortality risk in CKD patients who had undergone antiviral therapy for HCV. According to a recent longitudinal study (n=93,894 Taiwanese adults diagnosed with CKD), the 16-year cumulative incidence of death was greater in the untreated cohort, 58% (95% CI, 51.5–63.9%) as compared to the treated one, 41.4% (95% CI, 8.1% .54.1%), P<0.0001.4

The advent of direct-acting antiviral agents has profoundly changed the treatment of HCV not only in the general population, but also in ‘special populations’ (patients with CKD, HCV/HIV co-infection, HCV/HBV co-infection and unsuccessful previous DAA regimens). Sofosbuvir, a non-structural NS5B polymerase inhibitor, has been approved in 2013 and is now the backbone of many DAA treatment regimens. Sofosbuvir has large renal excretion and has been initially licensed for patients with a GFR more than 30mL/min. The SOF-free combination therapies grazoprevir/elbasvir and glecaprevir/pibrentasvir proved to be effective and safe in patients with advanced CKD, based on C-SURFER and EXPEDITION-4 trials, respectively.5

Numerous ‘real life’ studies have suggested the efficacy and safety of SOF-based regimens in those with an eGFR <30mL/min. AASLD now recommend all DAAs for GFR ≤30mL/min.5 We have conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis in order to assess efficacy and tolerability of SOF-containing therapies in the setting of stage 4–5 chronic kidney disease.

Material and methodsSearch strategy and data extractionWe followed PRISMA (Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis) statement guidelines to conduct this study.6 National Library of Medicine MEDLINE and manual searches were combined, as it had been previously demonstrated that a MEDLINE search alone may not be sensitive enough.7 The following key words were adopted: (sofosbuvir OR Sovaldi OR Harvoni OR Hepclusa OR Vosevi) AND (advanced chronic kidney disease OR severe kidney impairment OR end stage renal disease OR ESRD OR severe renal insufficiency) AND (Dialysis OR Haemodialysis OR Peritoneal Dialysis). General reviews, references from published clinical trials, letters to pharmacological companies, and Current Contents were also used. All articles were retrieved by a search from January 2013 to May 15, 2020. Data extraction was conducted independently by two investigators (F.F., and V.D.), and consensus was achieved for all data. Studies were compared to eliminate duplicate reports for the same patients, which included contact with investigators when necessary. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were pre-specified.

Criteria for inclusionTo be included in this systematic review, a clinical study had to fulfill a set of criteria. It had to be published as a peer-reviewed paper; report the results of SOF-based regimens; and use the sustained viral response (and/or dropout rate) as a clinical endpoint. We enrolled patients who underwent primary antiviral therapy (naïve patients) or those who had already completed an antiviral course (non responder or relapser patients).

Criteria for exclusionStudies were excluded if they reported inadequate data on treatment or measures of response. Patients with antibody response against human immunodeficiency virus were not considered. Studies that were only published as abstracts, case reports or interim reports were excluded; review articles were not evaluated for the current analysis. Studies reporting viral response rates by methods other than polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (i.e., bDNA assay) were excluded.

DefinitionsThe primary outcome of interest in this systematic review was SVR, as a measure of efficacy; SVR was defined as clearance of HCV viremia by PCR for at least 12 weeks after completion of antiviral therapy. Secondary end-points were the frequency of AEs, SAEs, and discontinuation rate of therapy due to SAEs, as measures of tolerability.

Quality assessmentThe methodological quality of included observational studies was assessed by two authors independently using the Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS).8 The NOS is usually used for observational studies. In the NOS scale, observational studies are scored across three categories: selection (up to four points), comparability (up to two points) and outcome of study participants (up to three points). Reports showing cumulative scores ranging between 4 and 6 are commonly defined as of fair quality. Disagreements in the above procedures were resolved by full discussions between the two independent reviewers with the corresponding author.

Statistical methodsOutcomes were analyzed on an intention-to-treat basis, that is, all patients included in these studies were considered for the calculation of the response rate, while patients without the end-point were classified as failures. Quantitative, pooled, summary estimates of the SVR and discontinuation rate of antiviral therapy (due to SAEs) across individual studies were generated using the random-effects model of Der Simonian and Laird.9 Confidence intervals for point estimates were computed adopting non-parametric (bootstrap) resampling methods. The estimate for each study was weighted inversely to its squared standard error when computing the overall estimate and its confidence intervals. The confidence intervals for the random-effects model were quoted, since the standard error under the fixed-effect model may be misleading, and the test for homogeneity was rejected. The Cochrane's chi-squared test (χ2) was adopted to quantify the heterogeneity, a value of <0.10 was considered indicative of a statistically significant heterogeneity.10 In addition, the consistency of effects across studies was measured by I2 index, and was considered significant if I2 value was 50% or greater.11 To further explore the origin of heterogeneity, we restricted the analysis to subgroups of studies defined by study characteristics such as country of origin (Asia, United States), study design, and DAA regimen, among others. Sensitivity analysis using a fixed-effects model was also performed to assess the consistency of results. We made a funnel plot to detect a publication bias in the relation exposure at hand. Every estimate was given with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The 5% significance level was adopted for alpha risk. All the statistical analyses were performed using Rev Man (Review Manager) 5.0, The Cochrane Collaboration (2020).

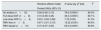

ResultsLiterature reviewOur electronic and manual searches identified 2747 articles that were considered potentially relevant and selected for review. Fig. 1 shows the flow diagram of literature review and study selection. A complete list of the 259 full-text articles reviewed is reported in supplementary file.

A total of 30 reports giving information on 1537 unique patients with stage 4–5 CKD were included in our meta-analysis.12–42 There was a 100% concordance between reviewers with respect to final inclusion and exclusion of studies based on predefined and exclusion criteria.

Patient characteristicsShown in Table 1 are the list of reports evaluated, the countries where the studies were conducted, the reference year and some background data. All the selected studies were conducted between 2015 and 2020. As listed in Table 2, the frequency of patients undergoing maintenance dialysis ranged from 0.7% to 100%. The gender distribution ranged from 22% to 100% male. Table 3 shows data on viral characteristics; it appears that the majority of patients had infection with HCV genotype 1. Information on the study design, and details on sofosbuvir-based regimens with DAAs (including sofosbuvir dose) are shown in Tables 2–3. We have not retrieved in the medical literature RCTs or simply controlled clinical trials of a comparison between SOF-based versus SOF-free regimen of HCV treatment in patients with advanced CKD (4–5 stage).

Baseline characteristics of studies included in the meta-analysis: background and clinical data.

| Author | Publication year | Country | Males (%) | Age |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bhamidimarri K. | 2015 | USA | 11 (73%) | 59.7±7.2 |

| Hundemer G. | 2015 | USA | 5 (83%) | 60±14 |

| Beinhardt S. | 2016 | Austria | NA | 50.6±10.9 |

| Saxena V. | 2016 | USA | 4 (22%) | NA |

| Nazario H. | 2016 | USA | 14 (82%) | 57 (46–69) |

| Desnoyer A. | 2016 | France | 10 (83%) | 52 (42–62) |

| Dumortier J. | 2017 | France | 36 (72%) | 60.5±7.5 |

| Aggarwal A. | 2017 | USA | 13 (93%) | 61±4.9 |

| Choudhary N. | 2017 | India | 7 (70%) | 48.5 (26–68) |

| Sperl J. | 2017 | Czech | 6 (100%) | 39 (25–53) |

| Cox-North P. | 2017 | USA | NA | NA |

| Saab S. | 2017 | USA | 8 (67%) | 62.2 (52–73) |

| Kumar M. | 2018 | India | 54 (76%) | 42 (22–80) |

| Singh A. | 2018 | India | 39 (83%) | 39.6±15.4 |

| Mehta R. | 2018 | India | 26 (68%) | 49.5 (36–58) |

| Akhil M. | 2018 | India | 15 (68%) | 49.7 (32–68) |

| He Y. | 2018 | China | 24 (73%) | 52.8 (19–74) |

| Taneja S. | 2018 | India | 40 (61.5%) | 42.9±13 |

| Butt A. | 2018 | USA | NA | NA |

| Garcia Agudo R. | 2018 | Spain | NA | NA |

| Surendra M. | 2018 | India | 13 (68%) | 44 (19–77) |

| Borgia S. | 2019 | Canada | 35 (59%) | 60 (33–91) |

| Eletreby R. | 2019 | Egypt | 205 (35.5%) | 52±17 |

| Wiegand J. | 2019 | Germany | NA | NA |

| Butt N. | 2019 | Pakistan | 11 (35%) | 36.5±10.9 |

| Seo H. | 2019 | Korea | 6 (67%) | 59.9 (27–82) |

| Goel A. | 2019 | India | 25 (61%) | 48 (19–75) |

| Debnath P. | 2020 | India | 14 (78%) | 39.4±8.3 |

| Michels F. | 2020 | Brazil | NA | NA |

| Poustchi H. | 2020 | Iran | 76 (73.8%) | 50.3±13.5 |

Baseline characteristics of studies included in the meta-analysis: clinical data Co=cohort, P=prospective, R=retrospective.

| Author | Dialysis, pts (%) | Cirrhosis (%) | Study design | HCV RNA, log10 IU/mL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bhamidimarri K. | 12 (80%) | 9 (60%) | Co, P | NA |

| Hundemer G. | 2 (33%) | 3 (50%) | Co, R | 6.47 |

| Beinhardt S. | 10 (100%) | 4 (40%) | Co, R | 6.1 ±0.8 |

| Saxena V. | 5 (28%) | 7 (39%) | Multicenter, longitudinal | 6.11 |

| Nazario H. | 15 (88%) | 8 (47%) | NA | NA |

| Desnoyer A. | 12 (100%) | 10 (83%) | Co, P | 6.59 (6.1–6.9) |

| Dumortier J. | 35 (70%) | 34 (68%) | Co, R | 6.41±5.63 |

| Aggarwal A. | 14 (100%) | 3 (21%) | Co, R | 6.92±7.09 |

| Choudhary N. | 10 (100%) | 2 (20%) | Co, P | 7 (5–8) |

| Sperl J. | 6 (100%) | 2 (33%) | Co, R | 6.61 |

| Cox-North P. | 20 (69%) | 13 (65%) | Co, R | NA |

| Saab S. | 12 (100%) | 1 (8%) | Co, R | 7.48±7.47 |

| Kumar M. | 11 (17%) | 17 (26%) | Co, P | 6.12 (3–7.8) |

| Singh A. | 39 (83%) | 12 (25%) | Co, P | 6.05 |

| Mehta R. | 38 (100%) | NA | Co, P | 5.75 (5.1–6.4) |

| Akhil M. | 22 (100%) | NA | Co, R | 6.42 |

| He Y. | 33 (100%) | 0 | Co, P | 6.8 (1.7–7.9) |

| Taneja S. | 54 (83%) | 21 (32%) | Co, P | 6.21 |

| Butt A. | NA | NA | National cohort | NA |

| Garcia Agudo R. | NA | NA | Co, R | NA |

| Surendra M. | 19 (100%) | 0 | Co, P | NA |

| Borgia S. | 59 (100%) | 17 (29%) | Co, P | 5.8 (3.1–7.7) |

| Eletreby R. | 4 (0.7%) | 107 (11%) | Multicenter cohort, R | 5.59 |

| Wiegand J. | NA | 107 (18%) | Co, R | NA |

| Butt N. | 31 (100%) | 0 | Co, P | NA |

| Seo H. | 9 (100%) | 2 (22%) | Co, R | 5.6 (2.9–6.7) |

| Goel A. | 31 (76%) | 5 (12%) | Co, R | 5.9 (4.1–9.9) |

| Debnath P. | 18 (100%) | 0 | Co, P | 5.37 |

| Michels F. | 34 (100%) | NA | Co, P | NA |

| Poutschi H. | 75 (72.8%) | 39 (37.9%) | Co, P | NA |

Baseline characteristics of studies included in the meta-analysis: clinical data.

| Author | HCV genotype 1 | SOF-based regimen | SOF-dose | Prior antiviral therapy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bhamidimarri K. | 15 (100%) | SOF/SMV | 400mg QD200mg QD | 9 (60%) |

| Hundemer G. | 6 (100%) | SOF+SMV (n=3)SOF+pegIFN±RBV (n=3) | 400mg QD | 3 (50%) |

| Beinhardt S. | 6 (60%) | SOF+DCV (n=5), SOF+SMV (n=3)SOF+pegIFN±RBV (n=2) | 400mg QD | 4 (40%) |

| Saxena V. | 14 (78%) | SOF+pegIFN, SOF+RBVSOF/LDV±RBV | 400mg QD | 10 (55%) |

| Nazario H. | 13 (76%) | SOF+SMV | 400mg QD | 3 (18%) |

| Desnoyer A. | 11 (92%) | SOF/LDV (n=1)SOF+RBV (n=1)SOF+DCV (n=8)SOF+SMV (n=2) | 400mg QD (n=7)400mg 48h (n=5) | 7 (58%) |

| Dumortier J. | 28 (56%) | SOF/SMV±RBV (n=11), SOF+DCV+RBV (n=30)SOF+pegIFN+RBV (n=9) | 400mg QD or400mg/48h | 36 (72%) |

| Aggarwal A. | 9 (64%) | SOF+SMV (n=6), SOF+pegIFN±RBV (n=2)SOF/LDV ±RBV (n=5), SOF+DCV (n=1) | 400mg QD (n=7)200mg QD (n=7) | 9 (64%) |

| Choudhary N. | 7 (70%) | SOF+RBV+pegIFN (n=8), SOF+DCV (n=2) | 400mg/48h | NA |

| Sperl J. | 0 | SOF+DCV | 200mg QD | 1 (17%) |

| Cox-North P. | 21 (72%) | SOF+RBV (n=2)SOF/LDV±RBV (n=20)SOF+DCV±RBV (n=7) | 400mg QD | 12 (43%) |

| Saab S. | 10 (83%) | SOF+RBV (n=9), SOF/LDV±RBV (n=3) | 400mg QD | NA |

| Kumar M. | NA | SOF+DCV (n=16), SOF/LDV (n=25)SOF+RBV (n=23) | 400mg QD | 13 (20%) |

| Singh A. | 32 (68%) | SOF+LDV (n=34), SOF+DCV (n=13) | 400mg QD | 2 (4%) |

| Mehta R. | 38 (100%) | SOF/LDV (n=12), SOF+DCV (n=26) | 400mg QD (n=13)200mg QD (n=13) | NA |

| Akhil M. | 14 (63%) | SOF+RBV | 400mg QD | 9 (41%) |

| He Y. | 7 (21%) | SOF+DCV | 200mg QD | 11 (33%) |

| Taneja S. | 42 (65%) | SOF+DCV | 200mg QD | 10 (15%) |

| Butt A. | NA | SOF+LDV+RBV (n=25), SOF+LDV (n=83) | NA | NA |

| Garcia Agudo R. | 8 (73%) | SOF/LDV±RBV (n=4)SOF+RBV (n=4), SOF+DCV+RBV (n=3) | 400mg QD | 3 (27%) |

| Surendra M. | 19 (100%) | SOF/LDV | 400mg/48h | 0 |

| Borgia S. | 27 (46%) | SOF+VEL | 400mg QD | 13 (22%) |

| Eletreby R. | NA | SOF+pegIFN+RBV (n=7)SOF+RBV (n=6), SOF+DCV (n=347)SOF+DAC+RBV (n=172)SOF+LDV (n=1), SOF+SMV (n=41)SOF+SMV+DAC+RBV (n=5) | 200mg QD | NA |

| Wiegand J. | NA | SOF+RBV (n=2), SOF+SMV+RBV (n=3)SOF+DCV+RBV (n=5), SOF/LDV+RBV (n=18) | 400mg QD | 21 (4%) |

| Butt N. | 10 (32%) | SOF+DCV | 400mg QD | 6 (19%) |

| Seo H. | 0 | SOF+RBV | 400mg QD | 2 (22%) |

| Goel A. | 17 (41%) | SOF+DCV | 200mg QD | 0 |

| Debnath P. | 12 (67%) | SOF/LDV (n=13), SOF+DCV (n=5) | 400mg QD | 0 |

| Michels F. | NA | SOF+DCV (n=25), SOF+SMV (n=8)SOF+pegIFN±RBV (n=1) | 400mg QD | NA |

| Poustchi H. | 53 (51.5%) | SOF+DCV | 400mgQD | 27 (26.2%) |

DCV=daclatasvir; LDV=ledipasvir; SOF=Sofosbuvir, SMV=simeprevir, VEL=velpatasvir.

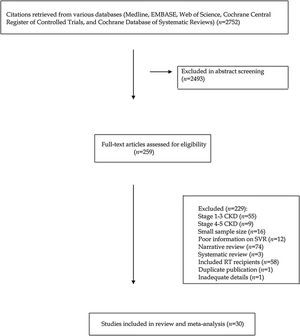

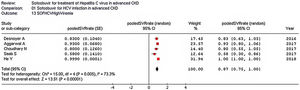

As listed in Fig. 2, the summary estimate for sustained viral response across the identified trials was 0.99 (95% CI, 0.99, 1.00; I2=99.8%). Visual inspection of the funnel plot suggested no publication bias.

Stratified analyses were undertaken to explain the heterogeneity across studies (Table 4). The analysis by the fixed-effects model yielded very similar findings to the random-effects model (data not shown). The pooled SVR rate significantly changed in some comparisons; the pooled SVR rate in the subgroup of studies having high average HCV RNA levels (≥6.5log10IU/mL) (Fig. 3) and advanced age (≥60 years), respectively was lower (P<0.001) (Table 4).

Summary estimates for sustained virological response (SVR) rate: primary and stratified analysis.

| Random-effects model SVR estimate (95% CI) | P-value (by χ2 test) | I2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| All studies (n=29) | 0.99 (0.97; 1.0) | 14,735.82 (0.0001) | 99.8% |

| Studies from the US (n=6) | 0.95 (0.91; 1.00) | 11.4 (0.04) | 56.3% |

| Studies from Asia (n=13) | 0.95 (0.91; 0.98) | 1,282,820.6 (0.00001) | 100.0% |

| Dialysis pts (n=15) | 0.98 (0.9; 1.0) | 102.96 (0.00001) | 86.4% |

| Males (>80%) (n=5) | 0.98 (0.97; 1.0) | 7.6 (0.11) | 47.4% |

| Recent studies (n=9) | 0.99 (0.97; 1.0) | 37.1 (0.00001) | 81.1% |

| Prospective studies (n=9) | 0.99 (0.98; 1.0) | 13.87 (0.03) | 56.7% |

| Genotype 1 (n=4) | 0.87 (0.8; 0.94) | 1.3 (0.70) | 0% |

| Advanced age (n=5) | 0.87 (0.78; 0.97) | 10.14 (0.04) | 60.6% |

| Full-dose SOF (n=13) | 0.99 (0.85; 1.0) | 33.29 (0.0009) | 64% |

| RBV-free regimens (n=14) | 0.99 (0.99; 1.0) | 7662.9 (0.0001) | 99.8% |

| Study quality>5 (n=11) | 0.98 (0.92; 1.0) | 26.4 (0.003) | 62.1% |

| High viremia (n=5) | 0.87 (0.75; 1.0) | 15.0 (0.005) | 73.3% |

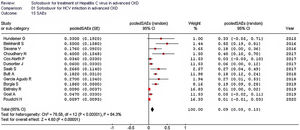

The pooled estimate for drop-out rate due to AEs was 0.02 (95% confidence intervals, −0.01; 0.04, I2=16.1%). The most frequent AEs requiring discontinuation of treatment were anemia (n=3), and worsening kidney function (n=3). The summary estimate of the rate of SAEs is shown in Fig. 4.

Table 5 shows the AEs reported in each study included in our meta-analysis. Common AEs were GI discomfort (n=51), fatigue (n=39), headache (n=38), and anemia (n=35).

Safety outcomes (Adverse Events, AEs).

| Author | AEs, type |

|---|---|

| Bhamidimarri K. | Fatigue (n=3), Itching (n=2), Anemia (n=2), Diarrhea (n=1) |

| Hundemer G. | Anemia (n=1), Leukopenia (n=1) |

| Beinhardt S. | Fatigue, Nausea, Cephalea, Photosensitivity, Anemia, Myalgia, Ascites |

| Saxena V. | Fatigue (n=3), Headache (n=1), Nausea (n=3), Worsening renal function (n=5), Anemia (n=6) |

| Nazario H. | Insomnia (n=2), Nausea (n=1), Headache (n=1), Anemia (n=1) |

| Desnoyer A. | Anemia (n=3), Headache (n=2), Itching (n=1), Muscle weakness (n=1), Cough (n=1), Anxiety (n=1) |

| Dumortier J. | Headache (n=16), Asthenia (n=14), Digestive discomfort (n=10), Insomnia (n=8) |

| Aggarwal A. | Headache (n=1), Fatigue (n=3), Acid reflux (n=1), Anemia (n=2) |

| Choudhary N. | Fatigue (n=4), Anemia (n=2) |

| Sperl J. | Diarrhea |

| Cox-North P. | Anemia (n=4) |

| Saab S. | Sepsis (n=3), Neurologic event (n=1) |

| Kumar M. | Fatigue, Headache, Insomnia, Nausea, Diarrhea, Anemia |

| Singh A. | Nausea (n=5), Insomnia (n=5), Headache (n=2), Pruritus (n=1) |

| Mehta R. | Headache, Joint pain, Muscle weakness, Itching |

| Akhil M. | Anemia (n=9) |

| He Y. | Nausea (n=13), Fatigue (n=13), Hyperkalemia (n=10), HBV reactivation (n=6), Anorexia (n=6), Constipation (n=3), Increased appetite (n=2), Hair loss (n=2), Joint pain (n=2), Hypoglycaemia (n=1), Dizziness (n=3), Elevated blood pressure (n=2), Insomnia (n=1), Blurred vision (n=1), Hematuria (n=1), Cough (n=1) |

| Taneja S. | Nausea (n=5), Insomnia (n=4), Headache (n=4), Pruritus (n=1) |

| Butt A. | Thrombocytopenia, Neutropenia |

| Garcia Agudo R. | Anemia, Fatigue, Headache |

| Surendra M. | Headache (n=1), Dizziness (n=1), AST/ALT elevation (n=8) |

| Borgia S. | Headache (n=10), Fatigue (n=8), Nausea (n=8), Vomiting (n=8), Insomnia (n=6) |

| Eletreby R. | NA |

| Wiegand J. | Fatigue, Headache, Nausea, Insomnia, Pruritus, Abdominal discomfort, Skin disorder, Diarrhea, Depressed mood, Anemia, Dyspnea, Restlessness, Alopecia |

| Butt N. | NA |

| Seo H. | Anemia (n=5), Insomnia (n=1), Fatigue (n=2), Itching (n=2), Nausea (n=1) |

| Goel A. | NA |

| Debnath P. | Headache (n=1), Dyspepsia (n=4), Fatigue (n=2) |

| Michels F. | Asthenia, Itching, Headache, Irritability, flu-like symptoms, dizziness, insomnia, low visual activity, nausea, anorexia, dysgeusia, depression, alopecia, diarrhea, exanthema |

| Poustchi H. | Headache (n=3), Diarrhea (n=4), Pruritus (n=3), Nausea (n=1) |

NA=not available.

Six studies (69 unique patients) reported eGFR levels at baseline- and post- antiviral therapy; no significant changes were found (Table 6). The frequency of serious or major AEs is reported in Table 7.

Safety outcomes (eGFR at baseline versus end of treatment or SVR12).

| Authors | Patients, n | Baseline eGFR (mean or median)a | EOT or SVR12 eGFR (mean or median)a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hundemer G. (2015) | 4 | 27.7 (26–29) | 34.7 (26–54) |

| Dumortier J. (2017) | 15 | 29 (20–34) | 27 (17–38) |

| Cox-North P. (2017) | 20 | 22.2 | 20 |

| Taneja S. (2018) | 11 | 24.8±3.9 | 24.4±3.6 |

| Singh A. (2018) | 8 | 19.9±9.4 | 17.9±8.5 |

| Kumar M. (2018) | 11 | 34 (21–63) | 35 (16–69) |

Safety outcomes (frequency of serious or major AEs).

| Author | SAEs, n | SAEs, type |

|---|---|---|

| Bhamidimarri K. | 0 | |

| Hundemer G. | 2 | AKI (n=1), Transfusion- dependent anemia (n=1) |

| Beinhardt S. | 5 | Sepsis (n=1), Peritonitis (n=1), Ascites (n=2), Pneumonia (n=1) |

| Saxena V. | 3 | eGFR decline (n=1), Cardiac disorder (n=1), anemia (n=1) |

| Nazario H. | 0 | |

| Desnoyer A. | 0 | |

| Dumortier J. | 3 | Transfusion-dependent anemia |

| Aggarwal A. | 0 | |

| Choudhary N. | 4 | Transfusion-dependent anemia (n=3)Thrombocytopenia (n=1) |

| Sperl J. | 0 | |

| Cox-North P. | 1 | Cardiac event |

| Saab S. | 4 | Sepsis (n=3), Neurologic event (n=1) |

| Kumar M. | 0 | |

| Singh A. | NA | |

| Mehta R. | 0 | |

| Akhil M. | 0 | |

| He Y. | 0 | |

| Taneja S. | 0 | |

| Butt A. | 25 | eGFR decline (>10%) (n=8)¾ Anemia (n=13), ¾ neutropenia (n=3), ¾ thrombocytopenia (n=1) |

| Garcia Agudo R. | 3 | Transfusion-dependent anemia (n=2)eGFR decline (>10%) (n=1) |

| Surendra M. | 0 | |

| Borgia S. | 11 | Cardiac disorder (n=2), Infection (n=5), Depression (n=2), Hemorrhage (n=1), Neoplasia (n=1) |

| Eletreby R. | 5 | eGFR decline (n=2), Anemia (n=2) |

| Wiegand J. | NA | Transfusion-dependent anemia, pneumonia, eGFR decline, liver failure |

| Butt N. | 0 | |

| Seo H. | 0 | |

| Goel A. | 2 | Pancreatitis (n=1), Ascites (n=1) |

| Debnath P. | 0 | |

| Michels F. | 0 | |

| Poustchi H. | 1 | Diarrhea |

There was some difference regarding the frequency of SAEs in the subsets of studies adopting DAA therapies including RBV or not (Table 8).

Summary estimates for severe adverse events (SAEs) rate: primary and stratified analysis.

| Random-effects model | P-value (by χ2 test) | I2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pooled SAEs (95% CI) | |||

| All studies (n=13) | 0.09 (0.05; 0.13) | 76.6 (0.0001) | 84.3% |

| Full-dose SOF (n=8) | 0.15 (0.06; 0.25) | 35.2 (0.0001) | 80.1% |

| Low-dose SOF (n=4) | 0.03 (−0.02; 0.08) | 7.72 (0.05) | 61.3% |

| RBV-free (n=3) | 0.07 (−0.01; 0.15) | 13.22 (0.001) | 84.9% |

| RBV-based (n=10) | 0.15 (0.07; 0.23) | 63.6 (0.0001) | 85.8% |

Although the identification of hepatitis C virus was made three decades ago, the natural history of HCV has been recently characterized. HCV chronic infection is a hepatic disease which may lead to cirrhosis and/or hepatocellular carcinoma but also a systemic disease with extra-hepatic manifestations either associated with a cryoglobulinemic disease or chronic inflammation. Recent data support a relationship between anti-HCV positive serologic status and increased risk of liver or cardiovascular disease-related mortality even in the dialysis population. According to our meta-analysis, the summary estimate for adjusted death risk (all-cause mortality) with HCV was 1.26 (95% CI, 1.18; 1.34) (P<0.0001). The overall estimate for adjusted death risk (cardiovascular mortality) was 1.8 (95% CI, 1.085; 1.29) (P<0.001).3

HCV is the only chronic viral infection that is virologically cured. In contrast to HIV or hepatitis B, one can obtain with the treatments a virologic cure, the so-called SVR, defined by undetectable HCV RNA at 12 weeks after the end of antiviral treatment which corresponds to a true virological cure. Solid organ transplantation of infected individuals who have obtained SVR does not lead to any infection, despite deep immunosuppression.

Up to November 2019, two DAA regimens (grazoprevir/elbasvir and glecaprevir/pibrentasvir) have been approved by the FDA to treat HCV infection in patients with stage 4–5 CKD including those on dialysis. These combinations may not be available in some countries or regions and sofosbuvir-based combinations may be all that is available. Both these combinations include NS3/NS4A protease inhibitors, which are not recommended for advanced liver disease. Sofosbuvir usually undergoes intracellular metabolism in the liver and the most important circulating metabolite of sofosbuvir (GS-331007) is mostly cleared by kidneys and achieves up to 456% increase in AUC in patients with creatinine clearance <30mL/min compared with those having intact kidneys.

Despite these pharmacokinetic data, preliminary reports suggested acceptable efficacy and safety of SOF-based combinations in HCV-infected patients with advanced CKD. Since then, two systematic reviews have been made43–44 but additional and large studies have been published. The efficacy and safety of SOF-based combinations in advanced CKD remains unclear.

According to our meta-analysis of observational studies (30 studies, n=1537 patients), the pooled SVR12 rate (99%) was excellent and was similar to that observed with non-SOF-based therapies. Stratified analysis reported a lower efficacy in the subset of studies enrolling high levels of HCV RNA and elderly patients (average age, >60 years), respectively. Elderly individuals have a great number of comorbidities and this could explain the low efficacy of SOF-based therapies in this group.

The current meta-analysis reported that the tolerance to SOF-based regimens in patients with stage 4–5 CKD was satisfactory. The aggregated rate of SAEs was 9%, the most common SAEs being anemia, and impaired eGFR. The incidence of SAEs was greater than that in patients with intact kidneys and this is in line with the safety risk factors typical of this population (advanced age, severe kidney impairment, cirrhosis, liver/kidney transplant recipient). SAEs were more common in the subset of studies adopting full dose sofosbuvir and RBV based therapies; we recommend caution when using DAA combinations containing RBV in advanced CKD. The frequency of drop-outs related to AEs was low (pooled drop-out rate due to adverse events, 2%).

A minority of the studies of our review gave detailed information on the relationship between sofosbuvir and progression of CKD. Six studies (n=69 patients) reported eGFR levels at baseline- and post- antiviral therapy; no consistent deterioration of kidney function was noted. Data on urinary changes were incomplete. Kumar et al.24 observed that the median (range) eGFR at baseline was 34 (21–63) mL/min/1.73m2. At 12 week after interrupting the treatment, median (range) eGFR was 34 (11–64) (n=11 patients).

The data regarding the relationship between SOF-based therapies and progression of CKD remains controversial. Some studies, conducted in patients with moderate CKD, found a decline in kidney function with sofosbuvir therapy.45 By contrast, HCV cure was associated with a 9.3mL/min per 1.73m2 improvement in eGFR during the 6-month post-treatment follow-up period.46 Despite this controversial evidence, serum creatinine should be carefully monitored during therapy with SOF in patients with CKD.

The results from the current meta-analysis present many limitations. First, all the reports were observational studies without control group- from a theoretical point of view, a randomized controlled trial with placebo gives the best evidence on the efficacy and safety of an intervention. Large size studies and long follow-up would be needed; the current availability of safe and effective drugs (DAAs) for the treatment of HCV makes the randomization to placebo not ethically acceptable. Second, large between-study heterogeneity was found; the methodological quality of the studies was on average not ideal and was one of the factors responsible for this. Our stratified analysis partially captured the heterogeneity we found. RBV in patients with CKD should be used with caution, as RBV accumulation can occur in CKD patients, who are already anemic at baseline. Thirdly, the large heterogeneity occurring in many comparisons suggested that all the studies of the current analysis are not functionally identical and this precluded the adoption of a fixed-effects model. Finally, individual data from each study (‘meta-analysis of individual participant data’) have been not retrieved, it is well known that this approach maximizes the power of the meta-analyses.

In conclusion, this meta-analysis shows an excellent efficacy of SOF-based combination therapy in patients with grade 4–5 CKD. Tolerance to SOF was satisfactory in this population – severe adverse events and treatment discontinuations were uncommon. Careful monitoring of kidney function should be performed during SOF-based therapy in CKD population.

Conflict of interestsAll the authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript.