Karyomegalic tubulointerstitial nephritis is a rare disease of uncertain etiology which has been linked to a genetic condition related to FAN1 gene. It is characterized by chronic tubulointerstitial nephritis with karyomegalic tubular epithelial cells (characteristic of the disease) lining the proximal and distal tubules and with enlarged hyperchromatic nuclei. It is a systemic entity that inevitably leads to end-stage renal disease.1 Involvement of other extrarenal organs may be present and is usually mild. It may consist of recurrent upper respiratory tract infections and liver impairment, as evidenced by elevated liver enzymes.2 The disease was first described by Burry in 1974,3 and the term karyomegalic nephritis was coined by Mihatsch in 1979.4 The exact pathogenesis of this disorder is unknown; however, it is thought to be associated with mitotic blockage linked to certain genotypes.5

A 51-year-old male patient with no cardiovascular risk factors, was admitted to the Nephrology Department of our Hospital due to acute renal failure (maximum creatinine 2.49mg/dl, CKD-EPI 28ml/min/1.73m2), fever and elevated liver enzymes. Urinalysis showed microhaematuria 5–10 red blood cells/field, proteinuria 350mg/24h and absence of eosinophils. A glomerular immunological study was performed, with normal immunoglobulins, negative antinuclear antibodies, normal complement (C3 and C4), normal electrophoresis in blood and urine. Given the persistent altered renal function without a clear cause, we decided to perform a renal biopsy.

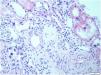

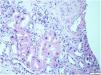

This biopsy, which included renal parenchyma consisting of cortex and medulla, with 32 glomeruli; 16 of them were sclerosed and the remaining showed slight segmental proliferation. The characteristic lesion is observed in the interstitium, at the level of the tubule cells, which show large, hyperchromatic and pleomorphic nuclei (Fig. 1). In the rest of the interstitium, histological lesions of acute tubular damage are observed (Fig. 2), associated with a patchy lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory infiltrate of moderate intensity, foci of fibrosis and tubular atrophy. The immunohistochemistry study showed negativity for LMP-1 (EBV), CMV, Herpes virus. Ki67 (cell proliferation index) is negative in atypical cells and less than 5% in tubular cells. The direct immunofluorescence study shows no significant deposits with the antisera studied. Electron microscopy showed a glomerulus with no significant lesions. Based on these data, the following diagnoses were made: Histological lesion pattern: (1) Global sclerosis in 50% of the glomeruli, with no defined lesion pattern in the non-sclerosed glomeruli. (2) Acute tubular damage at different stages with marked nuclear atypia in tubular epithelial cells. Note: The negativity of Ki67 in most of the atypical cells rules out the possibility of regenerative changes and suggests investigating the following entities as aetiological causes: heavy metal nephrotoxins, infection by viruses other than those already studied and karyomegalic interstitial nephritis.

Given these results, we proceeded to investigate possible infectious causes. Microbiological and serological tests for hepatitis B,C, HIV, toxoplasma, syphilis, rickettsia, leishmania, Herpes Simplex, CMV and EBV were all negative. Given that the patient worked in damp environments (in basements), we thought of Ochratoxin A, derived from fungus, this test was also negative. The patient was then referred to the Clinical Genetics Unit of our hospital to investigate a possible genetic etiology. With findings of homozygous mutation in the FAN1 gene (associated with karyomegalic interstitial nephritis with an autosomal recessive inheritance pattern). Carrier of the probably pathogenic variant c.1578-1G>T in homozygosis in the FAN1 gene.

This is one of the rare cases of karyomegalic interstitial nephritis with confirmed genetic study published in the literature. The prevalence of this entity is very low (<1/1,000,000) and there are very few cases described. FAN 1 is considered an effector of the Fanconi pathway, a DNA damage response signaling pathway dedicated to repair DNA inter-strand crosslink damage. However, no FAN1 mutations were detected in Fanconi anemia6 because Fanconi anemia involves other nucleases in its pathogenesis.7 These differences in cellular phenotypes lines may explain the lack of apparent phenotypic similarities between FAN1-negative individuals, compared to those who present karyomegalic interstitial nephritis, and Fanconi individuals who have clinical disease.8

We would like to highlight the fact that there is a high percentage of individuals treated with renal replacement therapy, diagnosed of fibrotic nephropathy, of unknown cause, in which a further study should be done as well as genetic causes should be considered. Also, to emphasize the importance of renal biopsy as a diagnostic tool, and the importance of giving a name and surname to the renal diseases we treat.