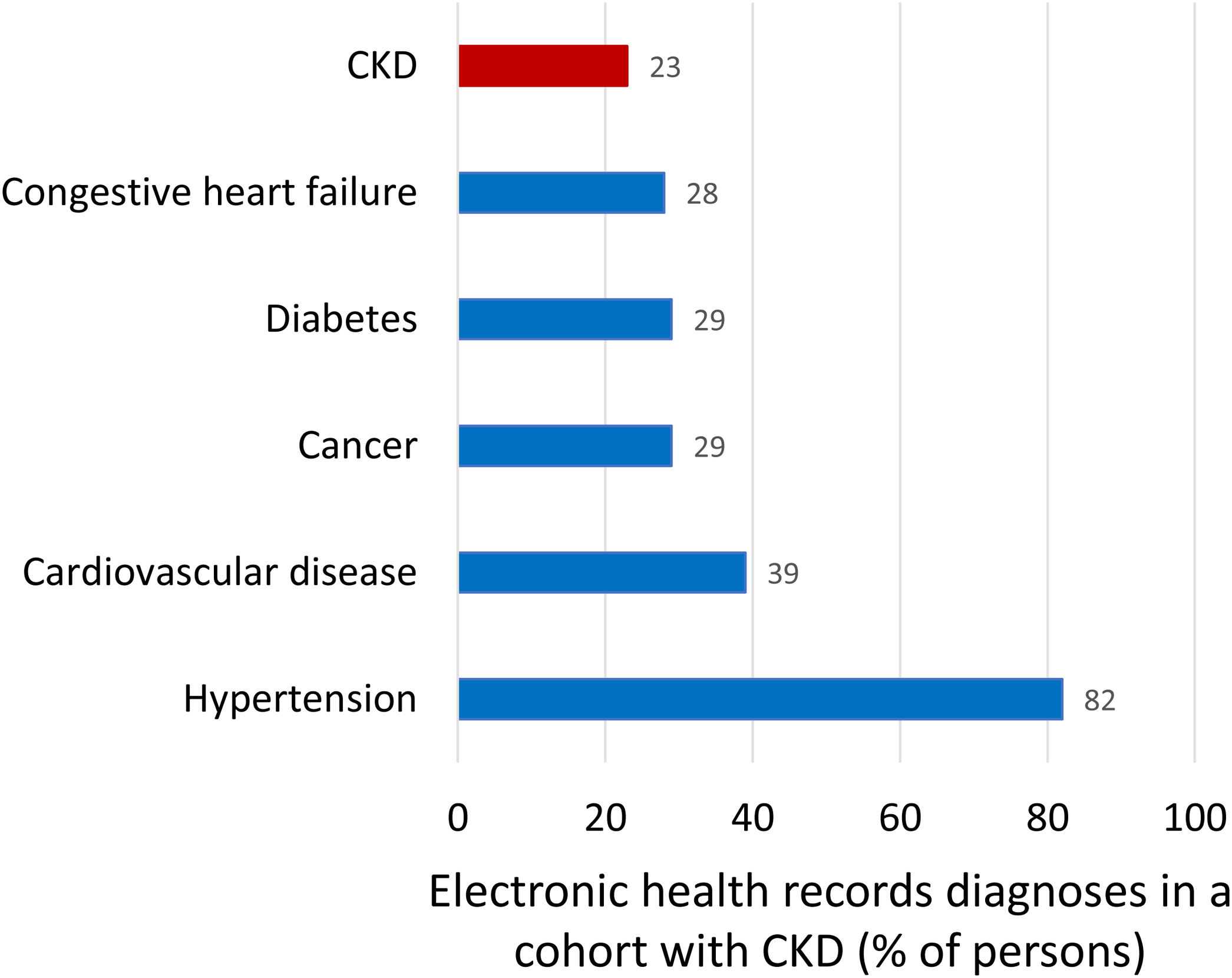

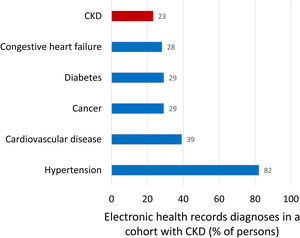

The uptake of the current concept of chronic kidney disease (CKD) by the public, physicians and health authorities is low. Physicians still mix up CKD with chronic kidney insufficiency or failure. In a recent manuscript, only 23% of participants in a cohort of persons with CKD had been diagnosed by their physicians as having CKD while 29% has a diagnosis of cancer and 82% had a diagnosis of hypertension. For the wider public and health authorities, CKD evokes kidney replacement therapy (KRT). In Spain, the prevalence of KRT is 0.13%. A prevalent view is that for those in whom kidneys fail, the problem is “solved” by dialysis or kidney transplantation. However, the main burden of CKD is accelerated aging and all-cause and cardiovascular premature death. CKD is the most prevalent risk factor for lethal COVID-19 and the factor that most increases the risk of death in COVID-19, after old age. Moreover, men and women undergoing KRT still have an annual mortality which is 10–100-fold higher than similar age peers, and life expectancy is shortened by around 40 years for young persons on dialysis and by 15 years for young persons with a functioning kidney graft. CKD is expected to become the fifth global cause of death by 2040 and the second cause of death in Spain before the end of the century, a time when 1 in 4 Spaniards will have CKD. However, by 2022, CKD will become the only top-15 global predicted cause of death that is not supported by a dedicated well-funded CIBER network research structure in Spain. Leading Spanish kidney researchers grouped in the kidney collaborative research network REDINREN have now applied for the RICORS call of collaborative research in Spain with the support of the Spanish Society of Nephrology, ALCER and ONT: RICORS2040 aims to prevent the dire predictions for the global 2040 burden of CKD from becoming true. However, only the highest level of research funding through the CIBER will allow to adequately address the issue before it is too late.

El impacto del concepto actual de enfermedad renal crónica (ERC) en la población, médicos y autoridades sanitarias ha sido bajo. Los médicos aún confunden la ERC con la insuficiencia renal crónica. En un manuscrito reciente, en una cohorte de personas con ERC, solo el 23% de los participantes fueron diagnosticados de ERC por sus médicos mientras que el 29% estaban diagnosticados de cáncer y el 82% de hipertensión. Para el público en general y las autoridades sanitarias, la ERC evoca la terapia de reemplazo renal (TRR). En España, la prevalencia de TRR es del 0,13%. La opinión predominante es que para aquellos en los que fallan los riñones, el problema se “resuelve” mediante diálisis o trasplante de riñón. Sin embargo, la principal carga sanitaria de la ERC es el envejecimiento acelerado y la muerte prematura de causa cardiovascular o de cualquier causa. La ERC es el factor mas prevalente de riesgo de mortalidad por COVID-19 después de la edad avanzada.

Además, los hombres y mujeres que se someten a TRR todavía tienen una mortalidad anual que es de 10 a 100 veces superior a sus pares de edades similares, y la esperanza de vida se reduce en alrededor de 40 años para jóvenes en diálisis y en 15 años para jóvenes con un injerto renal funcionante.

Se espera que la ERC se convierta en la quinta causa mundial de muerte para 2040 y la segunda causa de muerte en España antes de fin de siglo, época en la que 1 de cada 4 españoles tendrá ERC.

Sin embargo, para 2022, la ERC se convertirá en la única causa de muerte entre las 15 principales a nivel mundial que no cuenta con el respaldo de una estructura de investigación CIBER en España.

Los Principales grupos de investigación renal en España agrupados en la red de investigación colaborativa renal REDINREN han solicitado la convocatoria RICORS de investigación colaborativa en España con el apoyo de la Sociedad Española de Nefrología, ALCER y ONT: RICORS 040 tiene como objetivo evitar que se hagan realidad las terribles predicciones sobre la carga mundial de ERC para 2040. Sin embargo, solo el más alto nivel de financiación de la investigación a través del CIBER permitirá abordar adecuadamente el problema antes de que sea demasiado tarde.

The present manuscript summarizes key features of the concept of chronic kidney disease (CKD), as well as information on the current and future burden of CKD, and evidence that CKD as a health issue is underestimates by Spanish Health Research funding agencies. A more extensive report has been previously published.1 The signatories believe that the current and future burden of CKD, which is projected to hit hardly countries with long life expectancy and an ageing population such as Spain constitutes a national emergency that require the highest level available of research funding through the CIBER organization.

Chronic kidney disease: an evolving concept not well known outside nephrologyCKD is defined as abnormalities of kidney structure or function, present for >3 months, with implications for health.2 Criteria that by themselves diagnose CKD include glomerular filtration rate (GFR)<60ml/min/1.73m2 or evidence of kidney damage such as pathological albuminuria (urinary albumin creatinine ratio, UACR≥30mg/g), abnormal urine sediment, histology or imaging, abnormalities due to tubular disorders, or kidney transplantation.3 Diagnosing CKD implies assigning cause and G (GFR: G1 through G5) and A (albuminuria: A1 through A3) categories. G1 (GFR≥90ml/min/1.73m2) and A1 (UACR<30mg/g) categories are not diagnostic of CKD by themselves. Persons in category G1A1 require to fulfill an additional criterion to be diagnosed of CKD, such as imaging diagnostic of polycystic kidney disease (PKD).2,3

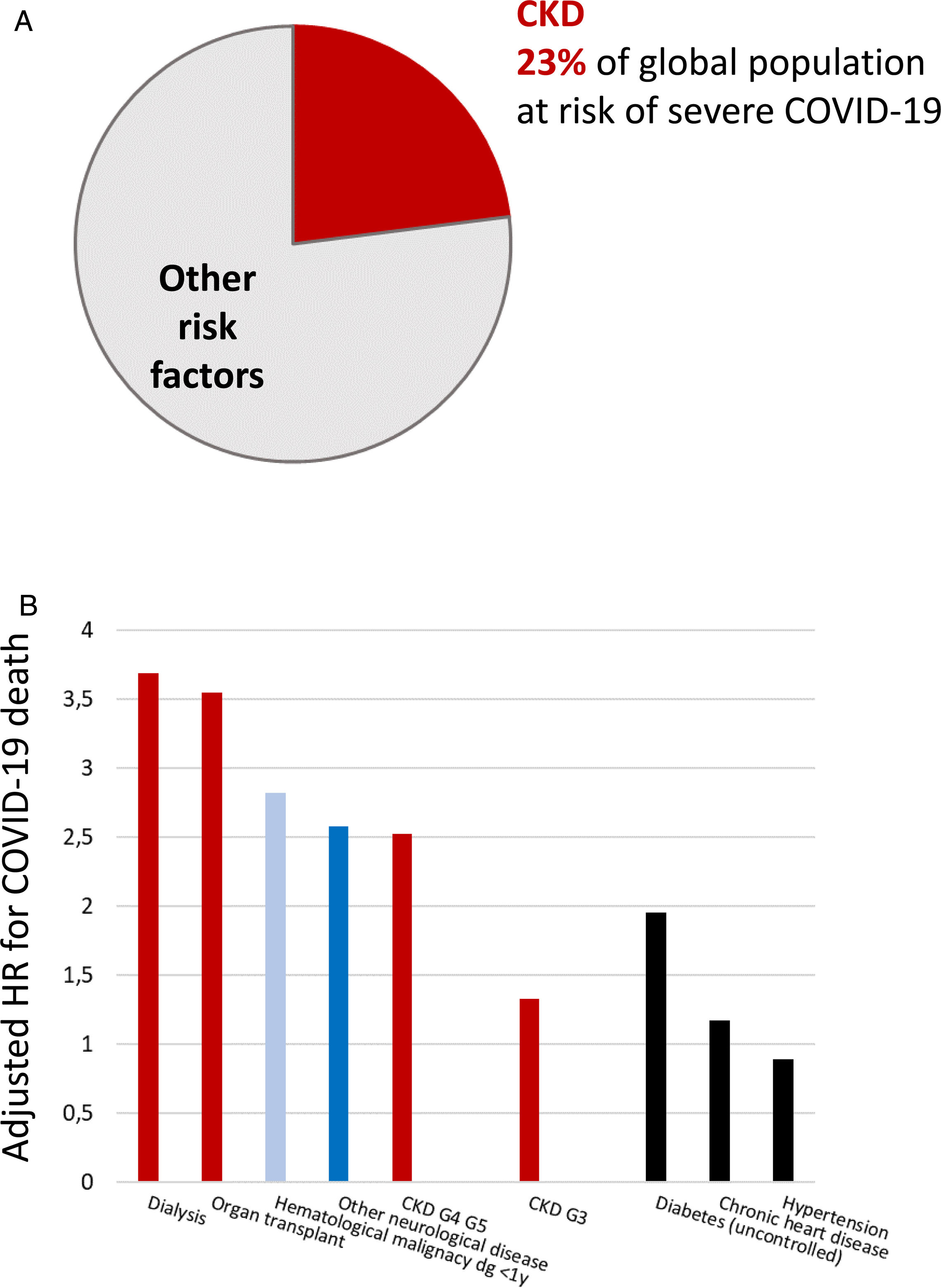

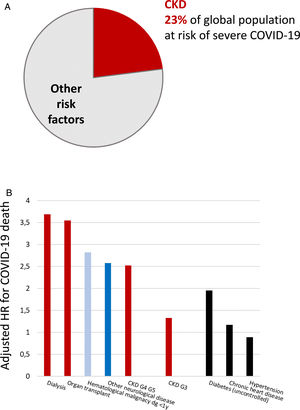

Persons with CKD are at an increased risk of progressing to require kidney replacement therapy (KRT), of all-cause and cardiovascular death, and of acute kidney injury (AKI).2,4–6 There is a bidirectional relationship between CKD and AKI. CKD is the main risk factor for AKI and AKI may accelerate CKD.7 AKI has a high mortality and increases the risk of death for over a year after the episode.7 AKI is also common, as around 5% of hospitalized patients develop in-hospital AKI.8 More recently, CKD has been identified as the most prevalent risk factor for lethal coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), and as the factor that most increased the risk of death in COVID-19 after older age9–11 (Fig. 1). AKI is also common in COVID-19 and a key risk factor for death.9

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is the most prevalent risk factor for severe COVID-19 and also the risk factor for severe COVID-19 that is associated with the highest risk of death, after old age. (A) CKD as a percentage of persons at risk of severe COVID-19 in a global scale. Data from 11. (B) Risk of death associated with pre-existent conditions in patients with COVID-19 in an adjusted analysis. Data from 10. Reproduced from 1 and 9.

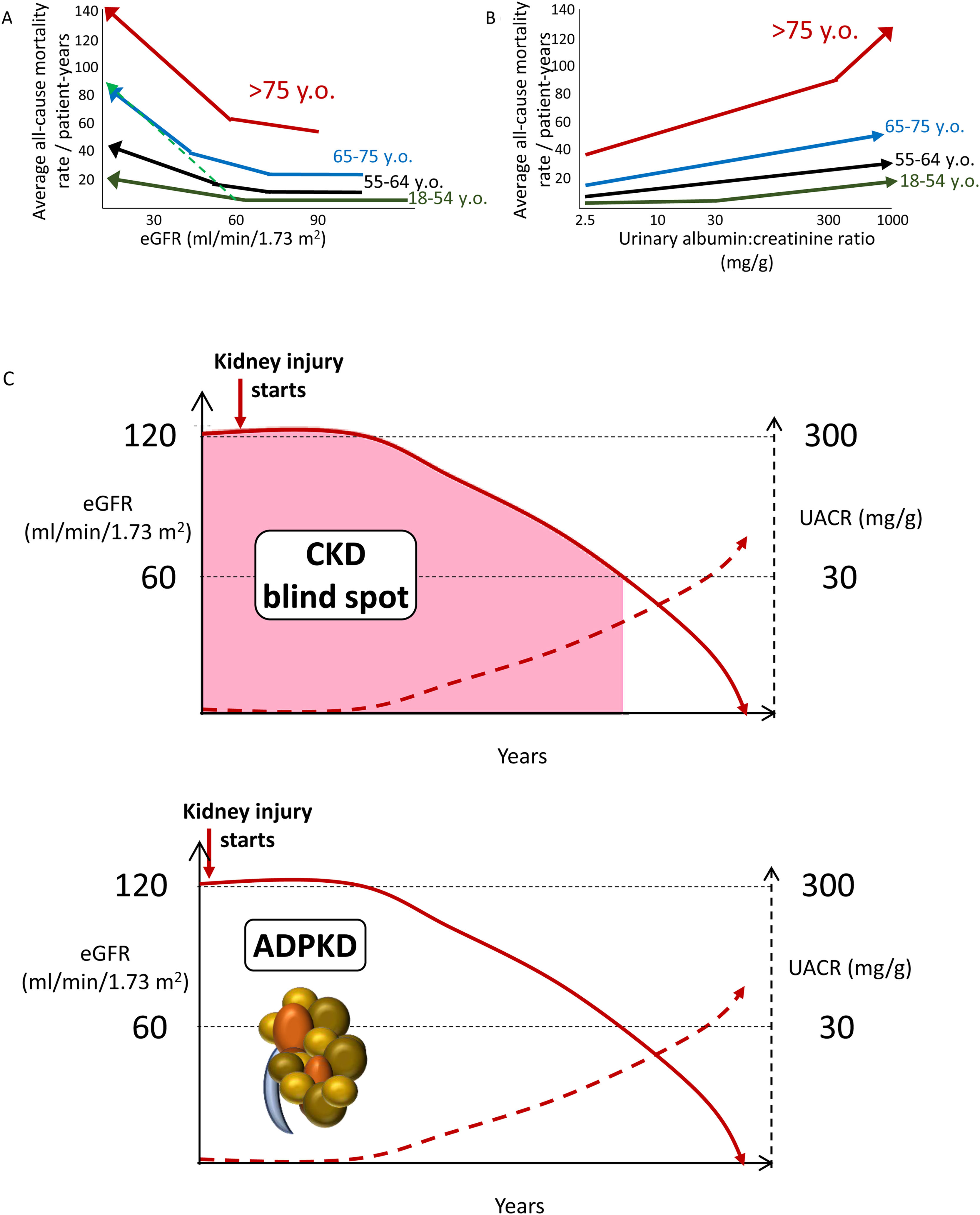

Increasing CKD categories are associated with increasing risk of all-cause and cardiovascular death, even in the elderly, thus questioning the concept of a “physiological” decrease in eGFR with age (Fig. 2A, B). Albuminuria as low as>2.5mg/g is already associated with an increased risk of premature death (Fig. 2B). Thus, the current albuminuria threshold used to diagnose CKD is a late event. Additionally, by the time GFR falls to 60ml/min/1.73m2, CKD has progressed unnoticed (potentially over years and even decades) to destroy>50% of the functioning kidney mass. This is the so-called blind spot in the diagnosis of CKD (Fig. 2C). In this regard, there is clear margin for earlier diagnosis and therapy of CKD. The autosomal dominant PKD paradigm illustrates the way to go: a diagnostic test (sonography) allows the diagnosis of CKD decades before patients fulfill any other criterion to diagnose CKD. Similar diagnostic tools are needed for other forms of CKD. Additional future criteria to diagnose CKD may be include genetic tests disclosing clearly pathogenic gene variants or urinary biomarkers beyond UACR, such as urinary peptidomics or urinary Klotho.12–14

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is associated with an increased risk of death even in the very elderly. All-cause mortality rate (absolute risk) for different eGFR (A) and UACR (B) values by age categories based on weighted average across cohorts, adjusted for covariates. A steeper slope at older age indicates a higher absolute risk difference associated with low eGFR as compared with younger age categories: the discontinuous green line represents the overlay of the risk for the very elderly on top of the risk line for the younger age range. Similar trends were observed for albuminuria. Conceptual representation of data presented in 5. In panel A, an increase in the risk of death observed in patients older than 55 years with higher eGFR values is not shown as this is thought to be an artifact depending on lower muscle mass of patients who were sicker at baseline. (C) The blind spot in CKD, as illustrated by autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. In ADPKD, CKD is present from birth, but using conventional criteria to diagnose CKD as low eGFR or pathological albuminuria, it can only be diagnosed 30–40 years later. However, there is a diagnostic test, sonography, that allows a much earlier diagnosis by demonstrating the presence of kidney cysts. Diagnostic tests should be developed that allow to diagnose CKD from other, non-ADPKD, causes decades earlier than current GFR or albuminuria criteria allow (figure from ref. 13). Reproduced from 1.

Kidney failure (end-stage kidney disease, G5, GFR<15ml/min/1.73m2) is the only form of kidney disease well known to the wider public, non-nephrologists and healthcare authorities. Non-experts usually equate the burden of CKD with the burden of KRT for kidney failure as the 64,000 persons on KRT in Spain consume 2.5–5.0% of the healthcare budget. However, the bulk of the health burden of CKD is not represented by KRT but by accelerated aging and premature death, as clearly quantified by Global Burden of Disease (GBD) data discussed below.15 Illustrating the lack of awareness of the CKD concept, in a recent report of a cohort of persons selected because they had CKD, as evidence for low eGFR for at least 3 months, CKD was only the sixth more common diagnoses after hypertension (82%), cardiovascular disease (39%), cancer (29%), diabetes (29%), heart failure (28%) (Fig. 3).16,17 Thus, only 23% of participants in the CKD cohort had been diagnosed by their physicians as having CKD while the number should be 100%.

Comorbidities diagnosed in a Swedish cohort of patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD), representing clinical conditions the treating physicians was aware of. Inclusion in the cohort required a researcher diagnosis of CKD based on the presence of two eGFR values below 60ml/min/1.73m2 separated by at least 90 days as per KDIGO definition. Patients on kidney replacement therapy were excluded. Note that among persons included in the cohort because researchers retrospectively diagnosed CKD, the physician in charge diagnosed cancer or diabetes more commonly than CKD. Data from 16, figure from 17.

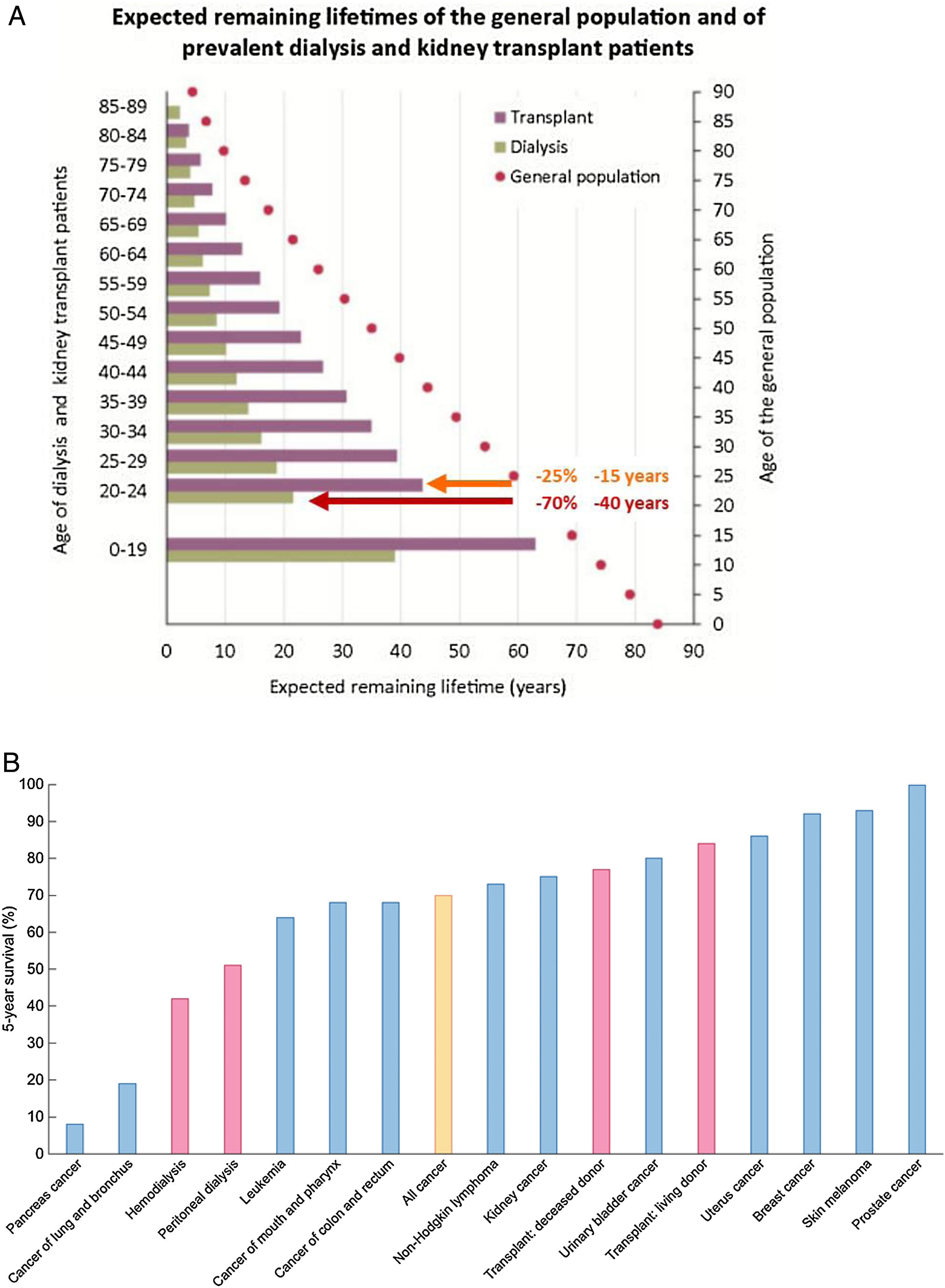

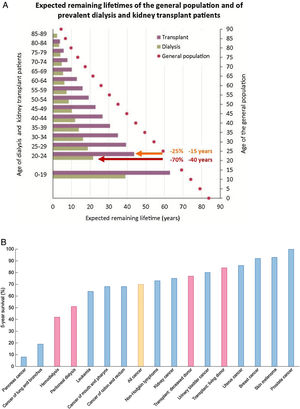

KRT is one of the success stories of health care in the 20th century and allows survival following failure of a vital organ. However, KRT is a failure of CKD management that, if successful, should have prevented CKD progression this stage. Indeed, in persons on KRT expected remaining lifetimes are severely reduced – by around 70% (40 years less) and by 25% (15 years less) for a 20-year-old on dialysis or with a functioning kidney graft, respectively.18,19 The absolute reduction in expected remaining lifetimes is milder at older ages, but the relative reduction in life expectancy remains constant up to age 89 years (Fig. 4A). Annual mortality of persons on KRT is up to 100-fold higher than for similar aged controls.6 Indeed, the 5-year survival of patients on dialysis is lower than for all forms of cancer combined20 (Fig. 4B).

Severely limited survival in persons on kidney replacement therapy (KRT). (A) Expected remaining lifetimes of the general population and of dialysis and kidney transplant patients in the European Renal Association (ERA-EDTA) Registry. Arrows and numbers depict relative and absolute reductions in life expectancy for young adults on KRT, either on dialysis (burgundy) or with a functioning kidney graft (orange).18,19. (B) Percent 5-year survival of KRT modalities (red bars) (hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, transplantation after deceased donation and transplantation after living donation) or after the diagnosis of cancer (blue bars). Only malignancies with an incidence over 3% of all cancers are illustrated. Orange bar: all cancers aggregated. Based on 2016 data. Source: 20. Reproduced from 1.

The most common cause of KRT in Spain is diabetes (25% of persons initiating KRT), followed by unknown (15%), “vascular”, glomerulonephritis (14%) and inherited kidney disease.18,19,21 While PKD is the only inherited kidney disease usually reported by large registries, recent Madrid and Catalonian KRT registry data found all inherited kidney diseases combined as frequent as glomerulonephritis.22 Inherited kidney diseases are frequently overlooked by physicians. Indeed, whole exome sequencing found monogenic kidney diseases in 9% of adult CKD, and in 17–34% of those with CKD of unknown cause.23,24

“Vascular” is labeled as hypertension in the European Renal Association – European Dialysis and Transplant Association (ERA-EDTA) Registry.18,19,21 In clinical practice, hypertension is usually listed as a cause when there is no other obvious etiology, following expert recommendation.25 This practice may replace an inadequate etiologic workup, downplaying the incidence of other causes of CKD while falsely boosting hypertension as cause (rather than as consequence) of CKD.26,27 Thus, there is no relationship between prevalence of hypertension and of hypertensive CKD in different countries.26 In African Americans, hypertensive nephropathy is known to represent a familial predisposition to CKD triggered by different causes, including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) or severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection.28

In the ERA-EDTA Registry data for all countries, the most common cause of incident KRT was unknown (27%, increasing to 39% if we add hypertension) followed by diabetes (20%), glomerulonephritis (11%) and PKD (5%). For prevalent KRT, the ranking is unknown (27%, increasing to 35% by adding hypertension) followed by glomerulonephritis (19%), diabetes (15%), and PKD (8%).18,19 Thus, a significant percentage of persons lack an etiological diagnosis, which precludes etiology-targeted therapy and early prevention campaigns. Among the fastest growing segment of CKD patients (those aged≥65 years), unknown and hypertension accounted for 43% of incident KRT patients, highlighting the need to define cause in the elderly. We propose that accelerated kidney aging may be a key contributor to CKD, including in the elderly, and are currently devising a working definition for accelerated kidney aging that spurs research in this field.

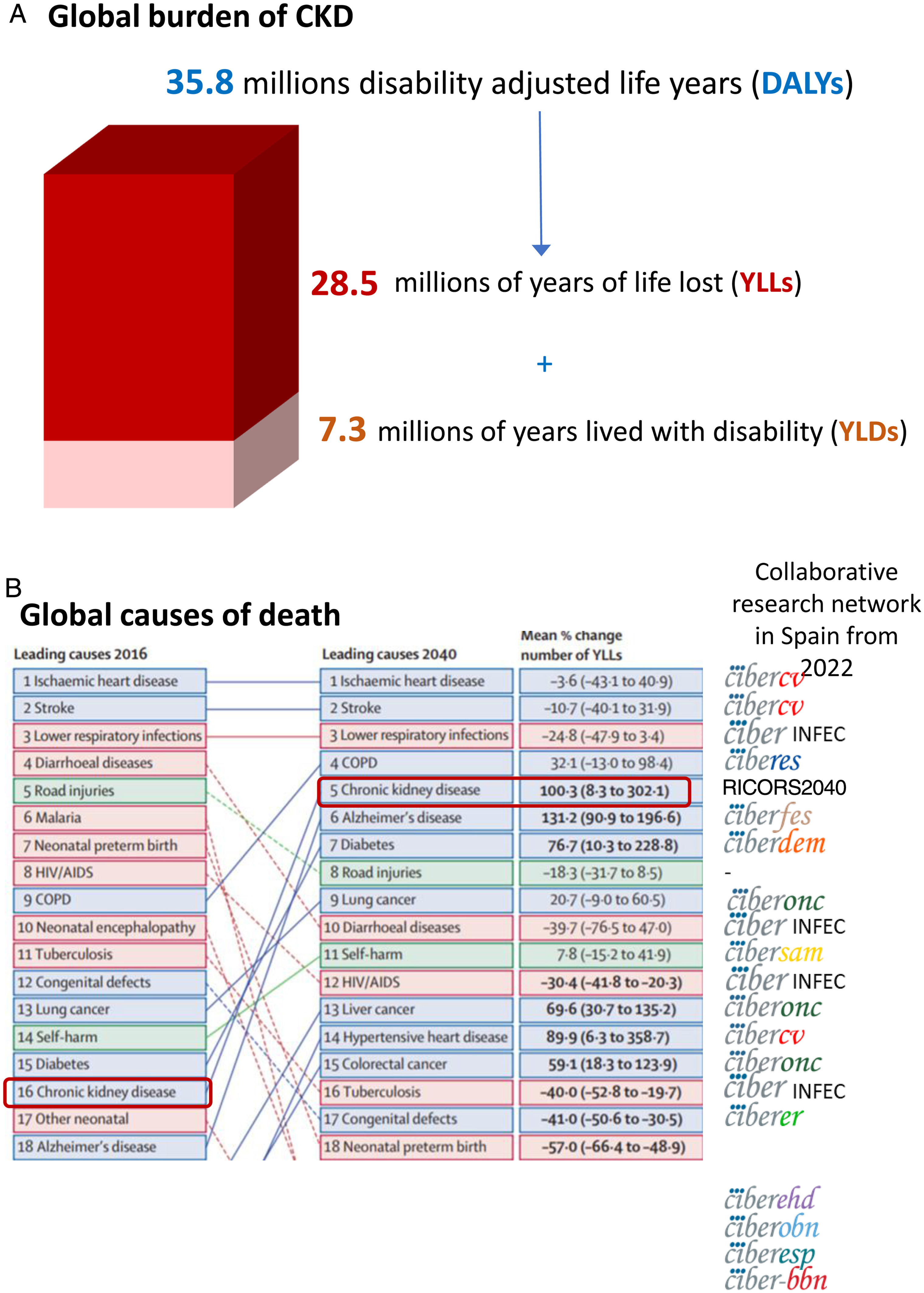

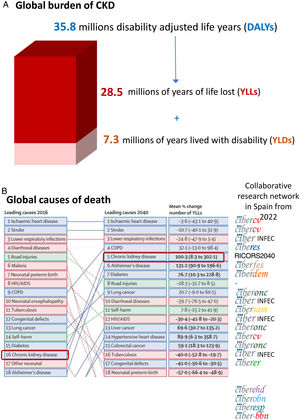

The growing burden of CKDGlobally, around 850 million persons have CKD.29 In 2017, 1.2 million people died from CKD globally and CKD resulted in 35.8 million disability adjusted life years (DALYs), most of them (>70%) not due to diabetic kidney disease, as well as in 7.3 million years lived with disability (YLD) and 28.5 million years of life lost (YLLs) (30) (Fig. 5A). However, there are large geographical differences in CKD burden. Age-standardized CKD DALY rates varied more than 15-fold between countries, a variability also evident within Spain and even within Spain autonomous communities.18,30 This illustrates the need for identification and correction of the drivers of a higher burden in certain regions.

Global burden of chronic kidney disease (CKD), according to the Global Burden of Disease (GDB) study. (A) 2017 global disability adjusted life years (DALYs), years lived with disability (YLD) and years of life lost (YLLs) due to CKD.30 (B) Major global causes of death in 2016 and predicted for 2040 according to the GBD study, ranked by YLLs.15 CKD is marked by empty rectangles. Logos to the right correspond to ISCIII-funded collaborative research networks in Spain that will address each cause from 2022. At the time of this writing, the status of kidney research in 2022 is still unclear. An infectious disease CIBER will be created in 2022, but at his point we are unaware of the logo. Thus, the CIBER logo was used and the word “INFEC” was added. Reproduced from 1.

GBD projected that CKD will become the 5th global cause of death by 204015 (Fig. 5B). YLLs due to CKD are expected to double by 2040, the fastest increase among major causes of death, after Alzheimer. By contrast, the burden of other major causes of death (e.g. ischemic heart disease −3.6% or stroke −10.7%) is already decreasing. CKD growth as a cause of death outpaces diabetes and research is needed in diabetes-independent causes of CKD. Spain GBD data identified CKD as the 8th cause of death. However, official Instituto Nacional de Estadistica (INE) data underestimated the burden of CKD, likely due to low awareness of the condition.31,32 Spain GBD identified CKD as the 2nd fastest growing cause of death, the 6th fastest growing cause of YLD and the 7th fastest growing cause of DALYs among the top 25 causes for each category.31,32 Projecting into the future the recent rate of increase of CKD in Spain GBD, CKD will become the 2nd cause of death, after Alzheimer, before the end of the century32 (Fig. 6A). This is likely an underestimation, as the progressive change in the age pyramid over the next few decades was not considered. Spanish projections may also apply to other countries with long life expectancy.

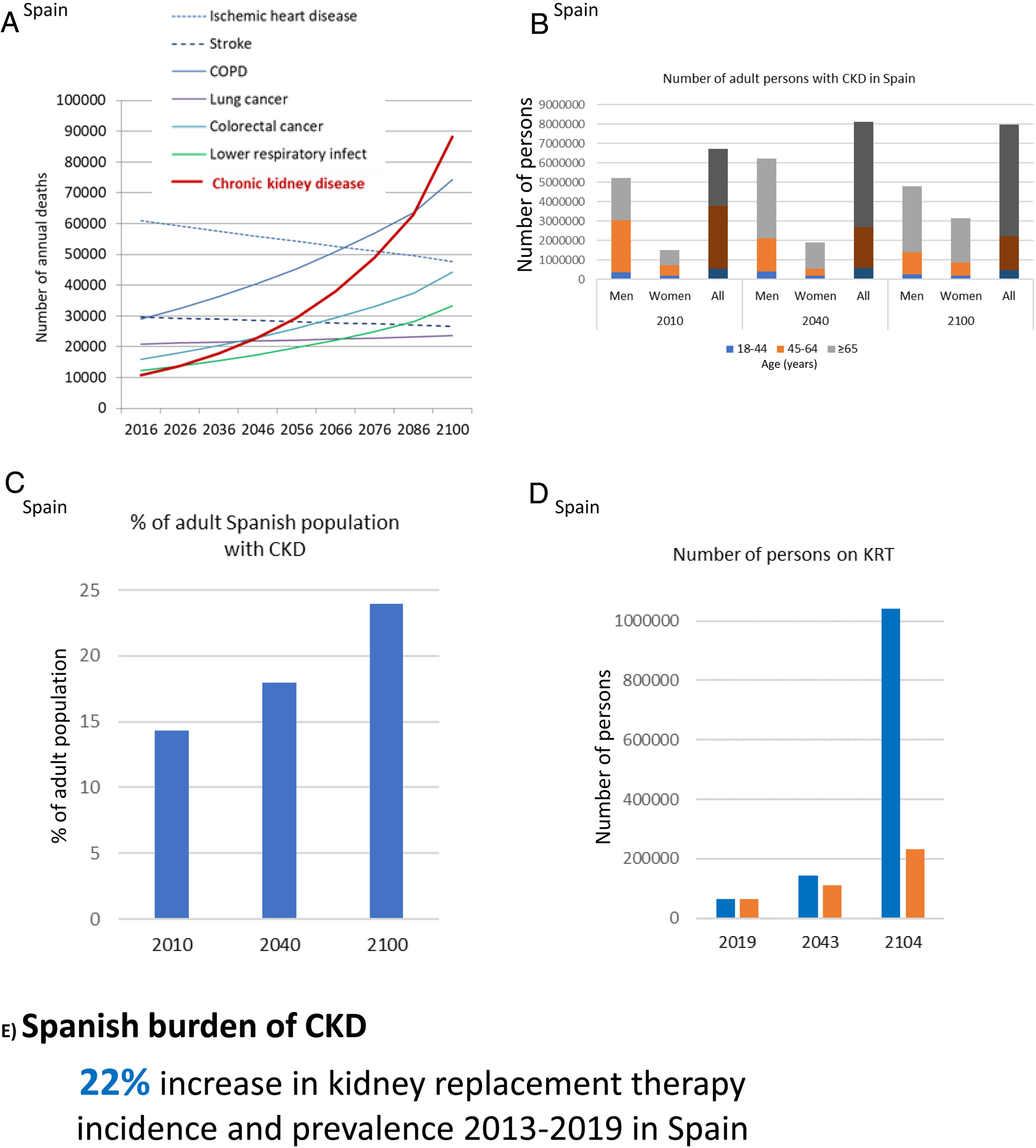

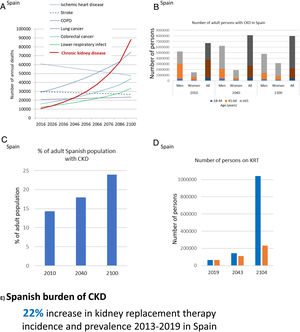

CKD burden and epidemiology in Spain. (A) Projected numbers of annual deaths in Spain by cause. Alzheimer not shown but it is projected to become the first cause of death before the end of the century, well above the others. Past growth according to GBD 2016 Spain was projected into the future.32 The projection did not consider the progressive aging of the Spanish population. Thus, it represents an underestimation of CKD-related deaths. (B) Number of adults with CKD in Spain, by gender and overall, according to the ERICA study from 2010 and projection into the future assuming the same prevalence of CKD by age category and considering changes in the Spanish population age pyramid according to the World Health Organization (WHO) predictions.33–35 Since the increasing mean age within each age category was not considered, this projection represents an underestimation.33,34 For each selected year, data for men, women and all are shown. (C) Percentage of Spanish adults with CKD in the ERICA study (2010) and projection into the future.33–35 (D) Number of prevalent persons on KRT in Spain in 2019 and projection into the future based on the 22% (12,000 persons) growth from 2013 to 2019.21 In blue, estimates according to hypothesized exponential growth; in orange, estimates according to linear growth. The progressive aging of the population was not accounted for, potentially underestimating the results. (E) Increase in incidence and prevalence of KRT from 2013 to 2019 in Spain. Reproduced from 1.

The population of Spain will become progressively older and decrease to around 23–33 million by 2100.33,34 In 2010, 14% of Spanish adults (6.7 million) had CKD.35 CKD was more common in men than in women and in those aged 45–64-years. Projecting these numbers into the future in the absence of changes to the current standard of care, assuming a constant prevalence of CKD within each age range and gender group and using WHO population prediction estimates, results in at least 8.12 million persons with CKD by 2040 and 7.96 million by 2100, which will represent 18% and 24% of the Spanish population, respectively (Fig. 6B, C). This is an underestimation, as progressive aging of the population (persons aged 65 years or more are estimated to increase from 17% in 2010 to 32% by 2040 and 35% by 2100) will also occur within the same age range category, and this would be associated with an increased prevalence of CKD within age categories, that we did not consider. Additionally, by 2040, most persons with CKD will be 65-year-old or older.

The prevalence of KRT in Spain is also increasing. It increased 38% from 2007 to 2019 (985–1367pmp) and the rate appears to be accelerating (it increased 14% from 2007 to 2013 and 22% from 2013 to 2019). At this rate of growth, the number of persons on KRT will hit 0.23–1.00 million by the end of the century, i.e. around 1–4% of the projected population of Spain at that time (Fig. 6D). The incidence of KRT also increased by 22% from 2013 to 2019 (125–152pmp)21 (Fig. 6E). A majority of persons on KRT in Spain (55%) have a functioning kidney graft. Thus, improving kidney and person outcomes in kidney graft recipients is a major aim in kidney research. As for CKD, KRT is also more common in men than in women. Thus, studies on CKD or KRT that do not split by gender may reflect the disease in men and studies addressing risk stratification, diagnosis and therapeutic approaches independently for men and for women are required. Furthermore, there are large regional differences (range of incident KRT 85–197pmp and of prevalent KRT 740–1567pmp for different Spanish regions), which are also observed within regions (e.g. in Madrid, range of incident KRT 50–200pmp and of prevalent KRT 980–1700pmp for different healthcare catchment areas). The causes of these differences are not fully understood, but it is critically important to define them in order to identify and target factors that generate CKD hotspots or benchmark potential healthcare contributors.36

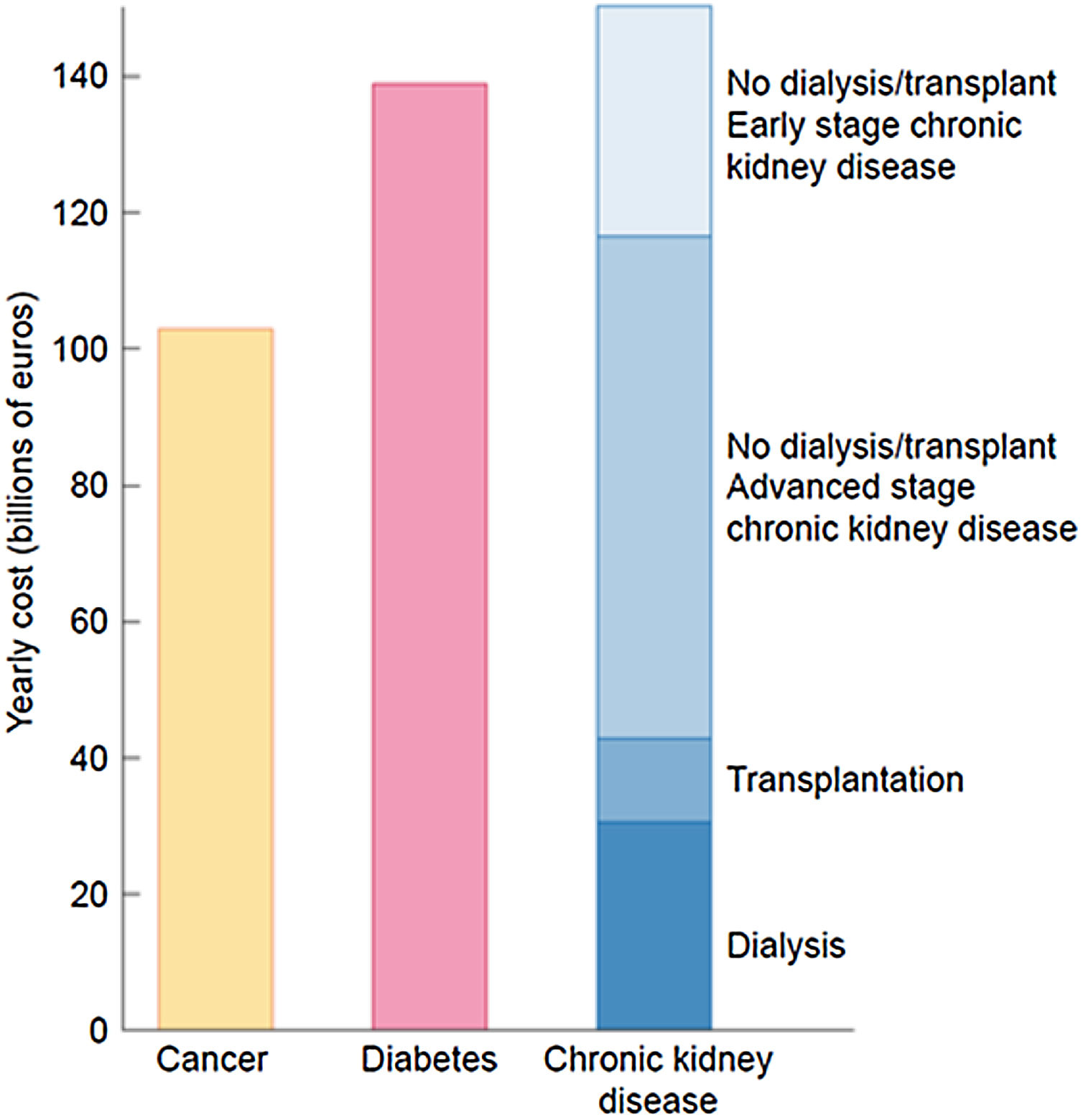

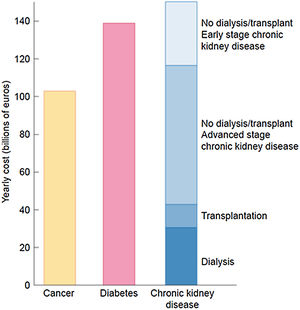

The burden of CKD is also economical. The extrapolated annual cost of all CKD is at least as high as that for cancer or diabetes and estimated at over 140 billion euros annually in Europe and over 130 billion dollars in the United States20,37 (Fig. 7).

The economic burden of CKD. Comparison of aggregated annual healthcare costs for Europe of cancer (yellow), diabetes mellitus (red) and CKD (different shades of blue). Costs of CKD are a composite of early CKD (stages/categories G1–G2 in native or transplant kidneys – light blue), more advanced stages of CKD (stages/categories G3–G5 not on dialysis in native or transplant kidneys), transplantation and dialysis (dark blue). Source: 20. Reproduced from 1.

From 2022, the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII, Spain Government Agency that funds health research) will fund the Redes de Investigación Cooperativa Orientadas a Resultados en Salud (RICORS, Cooperative Research Networks Focused on Results in Health) program of network research. This will replace the prior ISCIII-funded program of network research termed RETICS. The Spanish kidney research community, represented by the research groups integrated into the Kidney Research Network RETIC (RETIC RED de INvestigación RENal, REDINREN) and by several working groups of the Spanish Society of Nephrology (Sociedad Española de Nefrología, SEN), such as GLOSEN (glomerular disease working group) and GEENDIAB (diabetes working group), has submitted the RICORS2040 proposal to the RICORS call. RICORS2040 is supported by SENEFRO, the ERA-EDTA, ALCER (Federación Nacional de Asociaciones para la Lucha Contra las Enfermedades del Riñón, Spanish Kidney Patients Association) and ONT. RICORS2040 is focused on kidney diseases within one of the four thematic areas of the RICORS call: “Inflammation and immunopathology of organs and systems”.38 This thematic area includes kidney diseases and also non-transmissible immune system diseases, allergic diseases, multiple sclerosis and eye diseases.

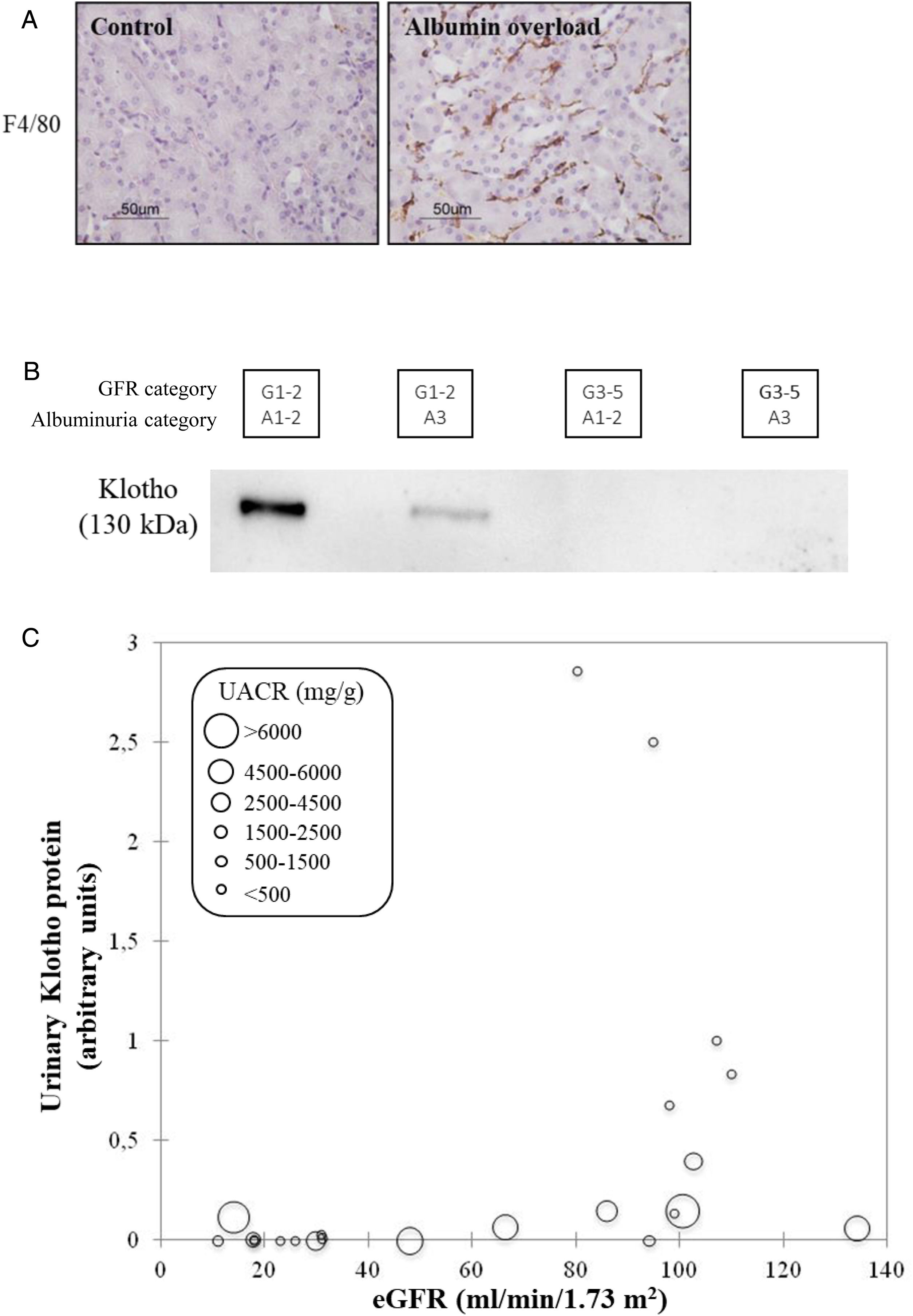

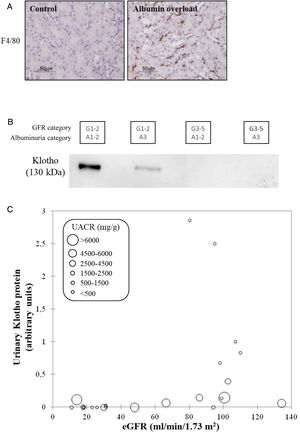

CKD as a chronic inflammatory disease. CKD is a local inflammatory disease that becomes a systemic inflammatory disease as it progresses. Activation of the master regulator of inflammation (NFκB), local expression of inflammatory cytokines and immune cell infiltrates are already observed in early stages of CKD and can be triggered by albuminuria, hyperglycemia and genetic defects, among others39,40 (Fig. 8A). Kidneys have multiple functions and GFR is just one of them. There is increasing evidence that production of the antiaging and anti-inflammatory factor Klotho is a key function of kidney tubules that is lost very early in the course of CKD (GFR category G1, that is, normal “kidney function”) partly in response to local inflammation and/or albuminuria41–43 (Fig. 8B). Loss of anti-inflammatory molecules and accumulation of uremic toxins leads to systemic inflammation, which is a key predictor of cardiovascular events and death in CKD, likely contributing to the accelerated biological aging that characterizes CKD.44,45

CKD as a local and systemic inflammatory disease leading to accelerated biological aging. (A) Albuminuria itself may trigger kidney inflammation as illustrated by the albumin overload model in mice: pathological albuminuria triggered interstitial macrophage (F4/80+ cells) infiltration (shown) while kidney function was preserved (not shown).40 Thus, albuminuria induces the loss of a key kidney function (production of the anti-inflammatory, anti-fibrosis and anti-aging protein Klotho) well before the kidney function assessed in routine clinical care (glomerular filtration rate) is lost. (B) Decreased urinary Klotho in persons with CKD G1/G2 (i.e. higher eGFR levels that, per se, are not diagnostic of CKD) with pathological albuminuria (consistent with cell culture and in vivo preclinical models in which inflammatory cytokines or albumin/albuminuria decreased tubular cell Klotho production by healthy tubular cells) and also in persons with CKD G3-5 (i.e. reduced eGFR, diagnostic, by itself, of CKD. In CKD G3-5 the decrease in Klotho is likely the consequence, in part, of decreased tubular cell mass. (C) Decreased urinary Klotho in persons with pathological albuminuria and preserved eGFR and also in persons with decreased eGFR irrespective of albuminuria. Vertical axis reflects urinary Klotho, horizontal axis reflects eGFR and diameter of circle reflects magnitude of albuminuria.40 Reproduced from 1.

Current versus future burden: The decade of the kidney. Current research should be guided by future projections of disease burden rather than by past statistics. RICORS2040 derives its name from its aim to prove wrong projections that CKD will become the 5th global cause of death by 2040.

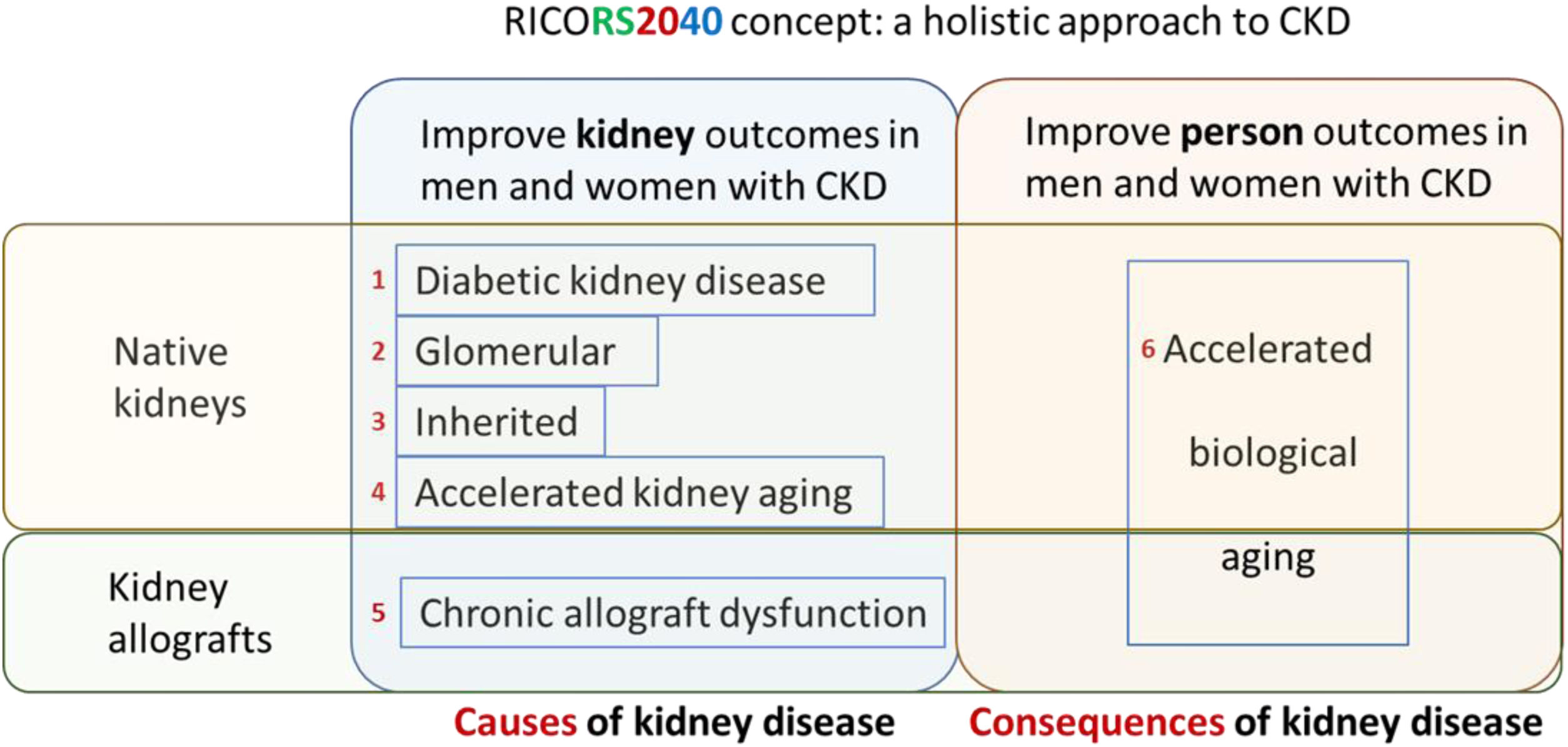

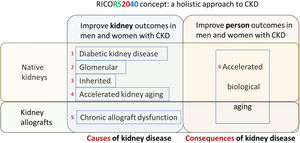

Emphasis on prevention. RICORS2040 is focused on preservation of native and graft kidney function and in improving outcomes in persons with CKD by preventing systemic consequences of CKD, collectively grouped into the concept of accelerated biological aging, including consequences of kidney transplantation and its therapy (Fig. 9), as a majority of persons on KRT in Spain carry a kidney graft. Thus, preventing the need for KRT in men and women with native kidneys or kidney grafts and improving kidney and person outcomes in kidney graft recipients are major aims of RICORS2040. Risk stratification and optimization of therapeutic approaches to improve quality of life and life expectancy in the dialysis population are also addressed.

RICORS2040 concept and overall structure and research aims. RICORS2040 aims at improving kidney and person outcomes in both men and women with CKD. There are two set of aims. The first set aims at improving the diagnosis and management of the most common causes of CKD to prevent or delay CKD progression. For this, the main causes of native kidney CKD (diabetes, glomerular, inherited/genetic) will be addressed, and the accelerated kidney aging concept will be explored as a final common pathway of CKD progression and as a potential cause of CKD in persons in whom no other cause is identified. Since the life expectancy of kidney allografts is markedly shorter than for native kidneys, chronic allograft dysfunction will also be explored. The second set aims to improve person outcomes by optimizing the diagnosis and management of the consequences of CKD (or of kidney transplantation therapy) on other organs and systems, what we have collectively named as the accelerated biological aging of CKD. Please note that aim 4 is focused on accelerated kidney aging as a cause of CKD and on kidney events, while aim 6 is focused on the impact of CKD on other organs and systems, that is, on accelerated biological aging of diverse organs and systems occurring as a consequence of CKD. Care will be taken to identify and optimize the management of gender-related issues and provide clinical guidance with specific information for men and for women. Reproduced from 1.

Men and women. There is mounting evidence that CKD course and complications are not the same in men and women and even that the cut-off points to define CKD may differ.46 However, we still use the same metric and the same cut-off points to diagnose CKD and for risk stratification in men and women, even knowing that creatinine excretion differs and thus, the denominator for UACR differs for men and for women. RICORS2040 will address the factors behind the gender gap in CKD burden and aims to provide clinical guidance for both men and women and to identify information gaps that preclude a gender-conscious approach to the diagnosis, risk stratification and treatment of CKD.

Addressing regional inequality. RICORS2040 will also address the factors behind geographical differences in CKD burden as it incorporates multiple centers from all over Spain. Specifically, kidney research and care centers from 12 of the 17 Spanish regions (Autonomous communities) encompassing 90% of the Spanish populations, are integrated into RICORS2040.

Clinical guidance should be implemented. A key issue hampering the achievement of health outcome targets in the poor implementation of clinical guidance documents. In this regard, clinical guidance documents are rarely validated in real-world clinical practice to assess potential shortcomings or barriers to implementation. RICORS2040 will use continuous improvement approaches to generate, validate and improve clinical guidance documents for different causes of CKD as well as for assessing and slowing the progression of CKD and of the associated accelerated biological aging of organs and systems in men and women with native kidneys or with kidney grafts. Testing the implementation of clinical guidance documents in a high number of centers from different regional health systems under real world conditions will allow to identify and correct most shortcomings and feasibility issues.

In summary, RICORS2040 is focused on decreasing the need for KRT by improving prevention, diagnosis, and therapy for major causes of CKD (diabetic, glomerular, inherited, accelerated kidney aging, the latter a concept that RICORS2040 is developing) in native kidneys and of chronic allograft nephropathy as well as on improving outcomes of men and women with CKD by preventing, identifying and treating major consequences of CKD or its therapy that contribute to the burden of accelerated aging and premature death (Table 1). This will be achieved through systematization of prior knowledge generated by its antecessor REDINREN and the international community into gender-conscious clinical guidance documents, novel research to address gaps of knowledge and monitoring of clinical guidance implementation to generate updated clinical guidance documents as output of RICORS2040.

Aims of RICORS2040.

| Specific aims: |

| 1. Improve kidney outcomes in men and women with diabetes or diabetic kidney disease (DKD) |

| Improve risk stratification in DKD to foster precision Nephrology |

| Evaluate novel strategies for kidney protection through therapeutic drug repositioning |

| Develop, evaluate and update Spanish Clinical Practice Guideline for detection and management of DKD. |

| 2. Improve kidney outcomes in men and women with primary glomerular disease |

| Improve risk stratification in glomerular disease to foster precision Nephrology |

| Evaluate novel kidney protective approaches in primary glomerular disease |

| Develop, evaluate and update clinical guidance documents |

| 3. Improve kidney outcomes in men and women with inherited kidney disease |

| Increase awareness of inherited kidney disease with special focus on glomerular and tubular kidney disease |

| Improve risk stratification in inherited glomerular disease to foster precision Nephrology |

| Identify genetic predictors of CKD progression |

| Develop, evaluate and update clinical guidance documents |

| 4. Define accelerated kidney aging as a cause of CKD and slow the loss of GFR in men and women |

| Develop a working definition of accelerated kidney aging |

| Develop tools to predict and assess rapid CKD progression |

| Test novel therapeutic approaches to kidney protection |

| Develop, evaluate and update clinical guidance documents |

| 5. Improve kidney allograft outcomes and improve the outcomes in men and women with a functioning kidney graft |

| Improve the outcome of chronic allograft nephropathy, decreasing graft loss |

| Limit the negative impact of immune suppressive therapies on comorbidities and life-threatening complications. |

| Develop, evaluate, and update clinical guidance documents for precision immunosuppression |

| 6. Improve the outcomes of men and women with CKD by targeting the accelerated biological aging which is a consequence of CKD |

| Develop novel risk stratification tools for cardiovascular disease and CKD-MBD to foster precision Nephrology |

| Improve the recognition and outcome of frailty |

| Evaluate the long-term safety and efficacy of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in persons with advanced CKD |

| Develop, evaluate, and update clinical guidance documents on key consequences of CKD, such as cardiovascular disease, CKD-MBD, frailty and susceptibility to severe SARS-CoV-2 infection |

The general aim of RICORS2040 is to improve kidney and person outcomes in men and women with CKD or at high risk of CKD. The name derives from the aim to prove wrong the dire predictions regarding the global burden of CKD by 2040, that closely reflect those for Spain: The GBD collaboration predicts that CKD will become the 5th global cause of death by 2040.

Despite CKD being the 5th predicted global cause of death by 2040, there is no confirmed Spanish research network on CKD from 2022 on. This is in contrast to a wider global movement to increase awareness of the health burden of CKD, summarized in the Decade of the Kidney (2020–2030) strategy in Europe and the US promoted by the American Association of Kidney Patients (AAKP) and adopted by the Advancing American Kidney Health (AAKH) initiative of the United States Government, the European Kidney Health Alliance (EKHA) and by patient associations across Europe.20,37,47–49 Moreover, even if RICORS2040 is funded, CKD lacks dedicated research centers (e.g. Spanish National Cancer Research Center, CNIO and Spanish National Cardiovascular Research Center, CNIC) or well-funded ISCIII CIBER research networks that fund research on all other major predicted 2040 global causes of death, except CKD14: ischemic heart disease (CIBERCV), stroke (CIBERCV and from 2022, stroke RICORS), infection (CIBER from 2022) and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (CiberRes). ISCIII research networks also fund projected 2040 causes of death ranked below CKD (e.g. CIBERONC for cancer and CIBERDEM for diabetes) (Fig. 5B). This represents a major, correctable gap in Spain's health research funding structure.

Note added in press: On October 13 2021, it was made public that RICORS2040 would be funded by ISCIII starting 2022.

Sources of supportREDINRENRD16/0009.

Note added in pressOn October 13 2021, it was made public that RICORS2040 would be funded by ISCIII starting 2022.

Conflict of interestAuthors are members of scientific and patient association with an interest in improving the outcomes and quality of life of persons with kidney disease. Alberto Ortiz is Editor in Chief for Clinical Kidney Journal, Maria Jose Soler is Associate Editor and Editor in Chief elect for Clinical Kidney Journal and Roser Torra and Jose Maria Cruzado are Associate Editors for Clinical Kidney Journal.

Asociación para la información y la investigación de las enfermedades renales genéticas (AIRG-E)

Marta Roger, Presidenta

Víctor Martínez Jiménez, Hospital Virgen de la Arrixaca de Murcia

José Carlos Rodríguez Perez, Hospital Universitario de Gran Canaria Dr. Negrin

Mónica Furlano, Fundació Puigvert

Laia Sans Atxer, Parc De Salut Mar

Federación Europea de Pacientes Renales (EKPF)

Daniel Gallego Zurro

Asociación para la lucha Contra las Enfermedades Renales (ALCER):

Carlos María Romeo Casabona

Daniel Gallego Zurro

Clemente Gómez Gómez

Pilar Pérez Bermúdez

Manuel Arellano Armisen

Santiago Albaladejo López

Inmaculada Gutiérrez Porras

Josefa Gómez Ruiz

José Manuel Martin Orgaz

Marta Moreno Barón

Sociedad Española de Nefrología (SENEFRO) council:

Patricia de Sequera Ortiz, Hospital Universitario Infanta Leonor

Gabriel de Arriba de la Fuente, Hospital Universitario de Guadalajara

Borja Quiroga Gili, Hospital Universitario de la Princesa

Gema Fernández Fresnedo, Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla

Sagrario Soriano Cabrera, Hospital Universitario Reina Sofía de Córdoba

Javier Pérez Contreras, Hospital General Universitario de Alicante

Miquel Blasco Pelicano, Hospital Clinic de Barcelona

Auxiliadora Mazuecos Blanca, Hospital Puerta del Mar

Mariano Rodríguez Portillo, Hospital Universitario Reina Sofía de Córdoba

J. Emilio Sánchez Álvarez, Hospital Universitario de Cabueñes

María José Soler Romeo, Hospital Universitario General Vall d’Hebrón

Manuel Gorostidi Pérez, Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias

Marian Goicoechea Diezhandino, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón

Sociedad Española de Trasplante (SET) council

Domingo Hernández Marrero, Trasplante Renal. Hospital Regional Universitario de Málaga

Constantino Fondevila Campo, Trasplante Hepático. Hospital Clinic de Barcelona

Eduardo Miñambres García, Coordinación Trasplantes. Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla

Dolores García-Cosío Carmona, Trasplante Cardiaco. Hospital 12 de Octubre

Armando Torres Ramírez, Trasplante Renal. Hospital Universitario de Canarias

Luis Muñoz Bellvis, Cirugía HBP. Complejo Asistencial Universitario de Salamanca

Marina Berenguer Haym, Trasplante Hepático. Hospital Universitario y Politécnico de la Fe

Manuel Barrera Gómez, Trasplante Hepático. Hospital Universitario Nuestra Señora de la Candelaria

José Manuel Cifrián Martínez, Grupo de Trasplante Pulmonar. Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla

Josep María Cruzado Garrit, Trasplante Renal. Hospital Universitario de Bellvitge

Rafael San Juan Garrido, Especialidad en Enfermedades Infecciosas. Hospital 12 de Octubre

Javier Briceño Delgado, Asociación Española de Cirugía. Hospital Universitario Reina Sofía de Córdoba

Marta Bodro Marimont, Grupo de Estudio de la Infección en el Trasplante (GESITRA)/Sociedad Española de Enfermedades Infecciosas y Microbiología Clínica (SEIMC), Hospital Clinic de Barcelona

María O. Valentín Muñoz, Organización Nacional de Trasplantes (ONT)

José Miguel Pérez Villares, Sociedad Española de Medicina Intensiva Critica y Unidades Coronarias (SEMICYUC). Hospital Universitario Virgen de las Nieves

Ángel Salvatierra Velázquez, Grupo de Trasplante de Pulmón de la Sociedad Española de Neumología y Cirugía Torácica (SEPAR). Hospital Universitario Reina Sofía de Córdoba

Luis Almenar Bonet, Sección Trasplante Cardíaco de la Sociedad Española de Cardiología. Hospital Universitario y Politécnico de la Fe de Valencia

Miguel Ángel Gómez Bravo, Sociedad Andaluza de Trasplantes. Hospital Virgen del Rocío

Francesc J. Moreso Mateos, Sociedad Catalana de Trasplantes. Hospital Universitario Vall d‘Hebrón

Manuel Muro Amador, Sociedad Española de Inmunología, Murcia. Hospital Virgen de la Arrixaca

Auxiliadora Mazuecos Blanca, Sociedad Española de Nefrología. Hospital del Mar

José A. Pons Miñano, Sociedad Española de Trasplante Hepático. Hospital Virgen de la Arrixaca

Amado Andrés Belmonte, Sociedad Madrileña de Trasplantes. Hospital 12 de Octubre

Amparo Solé Jover, Sociedad Valenciana de Trasplante. Hospital Universitario y Politécnico de La Fe

Daniel Casanova Rituerto, European Union of Medical Specialists (UEMS) Committe Board. Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla

Fernando Pardo Sánchez UEMS Committe Board. Clínica Universidad de Navarra

Fundación Renal Íñigo Álvarez de Toledo:

María Dolores Arenas MD PhD

Roberto Martin Hernández MD

Blanca Miranda Serrano MD PhD

RICORS2040/REDINREN:

Alberto Ortiz, Fundación Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria Fundación Jiménez Díaz

Ana B Sanz, Fundación Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria Fundación Jiménez Díaz

Adrian M Ramos, Fundación Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria Fundación Jiménez Díaz

Gina Córdoba-David, Fundación Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria Fundación Jiménez Díaz

Jorge García-Jiménez, Fundación Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria Fundación Jiménez Díaz

Miguel Fontecha-Barriuso Fundación Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria Fundación Jiménez Díaz

Juan Guerrero-Mauvecin, Fundación Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria Fundación Jiménez Díaz

Ana M. Lopez-Díaz, Fundación Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria Fundación Jiménez Díaz

María Dolores Sánchez-Niño, Fundación Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria Fundación Jiménez Díaz

Lara Valiño-Rivas, Fundación Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria Fundación Jiménez Díaz

Leticia Cuarental, Fundación Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria Fundación Jiménez Díaz

Marta Ribagorda, Fundación Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria Fundación Jiménez Díaz

Aranzazu Pintor-Chocano, Fundación Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria Fundación Jiménez Díaz

Chiara Favero, Fundación Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria Fundación Jiménez Díaz

Gloria Alvarez-Llamas, Fundación Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria Fundación Jiménez Díaz

Martín Cleary Catalina, Fundación Jiménez Díaz

Beatriz Fernández-Fernández, Fundación Jiménez Díaz

María Vanessa Pérez-Gómez, Fundación Jiménez Díaz

Emma Raquel Alegre de Montaner, Fundación Jiménez Díaz

Raúl Fernández Prado, Fundación Jiménez Díaz

Jorge Rojas Rivera, Fundación Jiménez Díaz

Ana María Ramos Verde, Fundación Jiménez Díaz

Sol Carriazo, Fundación Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria Fundación Jiménez Díaz

Sergio Luis-Lima, Fundación Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria Fundación Jiménez Díaz

Jinny Sánchez-Rodríguez, Fundación Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria Fundación Jiménez Díaz,

Soledad Pizarro Sánchez, Hospital Universitario Rey Juan Carlos

Marta Ruiz Ortega, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid

Emilio González Parra, Fundación Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria Fundación Jiménez Díaz

Sandra Rayego Mateos, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid

Pablo Javier Cannata Ortiz, Fundación Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria Fundación Jiménez Díaz

Laura Márquez Expósito, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid

Antonio Tejera-Muñoz, Fundación Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria Fundación Jiménez Díaz

Vanessa Marchant, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid

Lucia Tejedor-Santamaria, Fundación Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria Fundación Jiménez Díaz

Matilde Alique Agilar, Universidad de Alcalá de Henares

Fritz Diekmann, Fundación Privada Clínic. Hospital Clínic de Barcelona. Institut D’investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi I Sunyer (IDIBAPS)

Beatriz Bayes Genis, Hospital Clínic de Barcelona

Federico Oppenheimer Salinas, Hospital Clínic de Barcelona. Institut D’investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi I Sunyer (IDIBAPS)

María José Ramírez Bajo, Fundació Privada Clínic

Elisenda Bañon Maneus, Fundació Privada Clínic. Institut D’investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi I Sunyer (IDIBAPS)

Marta Arias Guillen, Hospital Clínic de Barcelona

Jordi Rovira Juárez, Institut D’investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi I Sunyer (IDIBAPS)

Marta Lazo Rodríguez, Fundació Privada Clínic

Ignacio Revuelta Vicente, Hospital Clínic de Barcelona. Institut D’investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi I Sunyer (IDIBAPS)

Josep Miquel Blasco Pelicano, Hospital Clínic de Barcelona

Luis Fernando Quintana Porras, Hospital Clínic de Barcelona. Institut D’investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi I Sunyer (IDIBAPS)

Pedro Ventura Abreu Aguiar, Hospital Clínic de Barcelona. Institut D’investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi I Sunyer (IDIBAPS)

Marc Xipell Font, Institut D’investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi I Sunyer (IDIBAPS)

Alicia Molina Andujar, Hospital Clínic de Barcelona

David Cucchiari, Hospital Clínic de Barcelona. Institut D’investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi I Sunyer (IDIBAPS)

Enrique Montagud Marrah, Hospital Clínic de Barcelona

Josep M, Campistol Plana, Hospital Clínic de Barcelona. Institut D’investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi I Sunyer (IDIBAPS)

Gastón Julio Piñeiro, Hospital Clínic de Barcelona

Carlos Martínez Salgado, Fundación Instituto de Estudios de Ciencias de la Salud de Castilla y León (IECSCYL). Institute of Biomedical Research of Salamanca (IBSAL)

Ana I. Morales Martín, Institute of Biomedical Research of Salamanca (IBSAL)

Francisco J.López Hernández, Institute of Biomedical Research of Salamanca (IBSAL)

Nélida Eleno Balboa, Institute of Biomedical Research of Salamanca (IBSAL)

Marta Prieto Vicente, Institute of Biomedical Research of Salamanca (IBSAL)

Isabel Fuentes Calvo, Institute of Biomedical Research of Salamanca (IBSAL)

Laura Ramudo González, Institute of Biomedical Research of Salamanca (IBSAL)

Laura Vicente Vicente, Institute of Biomedical Research of Salamanca (IBSAL)

Sandra M. Sancho Martínez, Institute of Biomedical Research of Salamanca (IBSAL)

Alfredo G. Casanova Paso, Institute of Biomedical Research of Salamanca (IBSAL)

Moisés Pescador Garriel, Institute of Biomedical Research of Salamanca (IBSAL)

Juan José Vaquero López, Universidad de Alcalá

Ana María Cuadro Palacios, Universidad de Alcalá

David Sucunza Saénz, Universidad de Alcalá

Patricia García García, Universidad de Alcalá

José Luis Aceña Bonilla, Universidad de Alcalá

Manuel A. Fernández Rodríguez, Universidad de Alcalá

Alberto Domingo Galán, Universidad de Alcalá

Estíbaliz Merino Marcos, Universidad de Alcalá

Javier Carreras Pérez-Aradros, Universidad de Alcalá

Rubén Manzano San José, Universidad de Alcalá

Francisco Maqueda Zelaya, Universidad de Alcalá

Ester Sans Panadés, Universidad de Alcalá

Álvaro González Molina, Universidad de Alcalá

Julia Atarejos Salido, Universidad de Alcalá

Roser Torra Balcells, Fundació Puigvert

Elisabet Ars Criach, Fundació Puigvert

Montserrat Díaz Encarnación, Fundació Puigvert

Lluis Guirado Perich, Fundació Puigvert

Monica Furlano, Fundació Puigvert

Cristina Canal Girol, Fundació Puigvert

Yolanda Arce Terroba, Fundació Puigvert

Marc Pybus Oliveras, Fundació Puigvert

Laia Ejarque Vila, Fundació Puigvert

Nuria Serra Cabañas, Fundació Puigvert

Carme Facundo Molas, Fundació Puigvert

Irene Silva Torres, Fundació Puigvert

Santiago Lamas Pelaez, Centro de Biología Molecular Severo Ochoa

Carlos Rey Serra, Centro de Biología Molecular Severo Ochoa

Carolina Castillo Torres, Hospital Príncipe de Asturias

Jessica Paola Tituaña Fajardo, Centro de Biología Molecular Severo Ochoa

José Ignacio Herrero Lahuerta, Centro de Biología Molecular Severo Ochoa

Verónica Miguel Herranz, Centro de Biología Molecular Severo Ochoa

Mariano Rodriguez Portillo, Hospital Reina Sofía

Alejandro Martin Malo, Hospital Reina Sofía

Sagrario Soriano Cabrera, Hospital Reina Sofía

Juan Rafael Muñoz Castañeda, Instituto Maimonides de Investigación Biomédica de Córdoba (IMIBIC)

María Encarnación Rodríguez Ortiz, Instituto Maimonides de Investigación Biomédica de Córdoba (IMIBIC)

Julio Manuel Martínez Moreno, Instituto Maimonides de Investigación Biomédica de Córdoba (IMIBIC)

Ana Isabel Raya Bermúdez, Instituto Maimonides de Investigación Biomédica de Córdoba (IMIBIC)

Rafael Santamaría Olmo, Hospital Reina Sofía

Fátima Guerrero Pavón, Instituto Maimonides de Investigación Biomédica de Córdoba (IMIBIC)

Cayetana Moyano Peregrin, Hospital Reina Sofía

Escolástico Aguilera Tejero, Instituto Maimonides de Investigación Biomédica de Córdoba (IMIBIC)

Ignacio Lopez Villalba, Instituto Maimonides de Investigación Biomédica de Córdoba (IMIBIC)

Andrés Carmona Muñoz, Instituto Maimonides de Investigación Biomédica de Córdoba (IMIBIC)

María Victoria Pendon Ruiz De Mier, Hospital Reina Sofía

Carmen María Pineda Martos, Instituto Maimonides de Investigación Biomédica de Córdoba (IMIBIC)

Rodrigo López Baltanas, Instituto Maimonides de Investigación Biomédica de Córdoba (IMIBIC)

Cristian Rodelo Haad, Hospital Reina Sofía

Marcella Franquesa Bartolomé, Fundación Instituto Investigación Germans Trias I Pujol

Ricardo Lauzurica Valdemoros, Hospital Germans Trias I Pujol

Francisco Enrique Borras Serres, Fundación Instituto Investigación Germans Trias I Pujol

Maruja Navarro Díaz, Hospital Germans Trias I Pujol

Francisco Javier Juega Mariño, Hospital Germans Trias I Pujol

Laura Cañas Sole, Hospital Germans Trias I Pujol

Maria Isabel Troya Saborido, Hospital Germans Trias I Pujol

Jordi Soler Majoral, Hospital Germans Trias I Pujol

Marina López Martínez, Hospital Germans Trias I Pujol

Emilio Rodrigo Calabia, University Hospital Marqués de Valdecilla/IDIVAL, University of Cantabria

Juan Carlos Ruiz San Millán, University Hospital Marqués de Valdecilla/IDIVAL, University of Cantabria

Marcos López-Hoyos, University Hospital Marqués de Valdecilla/IDIVAL, University of Cantabria

Adalberto Benito-Hernández, University Hospital Marqués de Valdecilla/IDIVAL, University of Cantabria

Gema Fernández Fresnedo, University Hospital Marqués de Valdecilla/IDIVAL, University of Cantabria

David San Segundo, University Hospital Marqués de Valdecilla/IDIVAL, University of Cantabria

Rosalía Valero, University Hospital Marqués de Valdecilla/IDIVAL, University of Cantabria

Eliécer Coto García, Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias

Juan Gómez De Ona, Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias

Elias Cuesta Llavona, Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias

Fernando Santos Rodríguez, Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias

Rebeca Lorca Gutiérrez, Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias

Helena Gil Peña, Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias

Manuel Gorostidi Pérez, Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias

Domingo Hernández Marrero, Instituto de Investigación Biomédica de Málaga (IBIMA)

Verónica López, Hospital Regional Universitario de Malaga/IBIMA

Eugenia Sola, Hospital Regional Universitario de Malaga/IBIMA

Mercedes Cabello, Hospital Regional Universitario de Malaga/IBIMA

Abelardo Caballero, Hospital Regional Universitario de Malaga/IBIMA

Myriam León, Hospital Regional Universitario de Malaga/IBIMA

Pedro Ruiz, Hospital Regional Universitario de Malaga/IBIMA

Juana Alonso, Hospital Regional Universitario de Malaga/IBIMA

Juan Navarro-González, Hospital Nuestra Sra. Candelaria, Tenerife

María Del Carmen Mora-Fernández, Hospital Universitario Nuestra Señora de Candelaria

Javier Donate-Correa, Hospital Universitario Nuestra Señora de Candelaria

Ernesto Martín-Nuñez, Hospital Universitario Nuestra Señora de Candelaria

Nayra Pérez Delgado, Hospital Universitario Nuestra Señora de Candelaria

Secundino Gigarrán-Guldris, Hospital Da Costa, Burela

José Carlos Rodríguez Pérez, Hospital Universitario Dr. Negrín

José Luis Górriz Teruel, Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valencia

Alberto Martínez Castelao, Hospital Universitario Bellvitge, Hospitalec, Barcelona

José Manuel Valdivielso Revilla, Instituto de Investigación Biomédica de Lleida. Fundación Dr. Pifarre (IRBLLEIDA)

Cristina Martínez Martínez, Instituto de Investigación Biomédica de Lleida. Fundación Dr. Pifarre (IRBLLEIDA)

Milica Bozic Stanojevic, Instituto de Investigación Biomédica de Lleida. Fundación Dr. Pifarre (IRBLLEIDA)

Eva Castro Boque, Instituto de Investigación Biomédica de Lleida. Fundación Dr. Pifarre (IRBLLEIDA)

María Nuria Sans Rosell, Instituto de Investigación Biomédica de Lleida. Fundación Dr. Pifarre (IRBLLEIDA)

Virtudes Maria De Lamo, Instituto de Investigación Biomédica de Lleida. Fundación Dr. Pifarre (IRBLLEIDA)

Juan Miguel Díaz Tocados, Instituto de Investigación Biomédica de Lleida. Fundación Dr. Pifarre (IRBLLEIDA)

Alicia Garcia Carrasco, Instituto de Investigación Biomédica de Lleida. Fundación Dr. Pifarre (IRBLLEIDA)

Marcelino Bermúdez López, Instituto de Investigación Biomédica de Lleida. Fundación Dr. Pifarre (IRBLLEIDA)

Maite Caus Enriquez, Instituto de Investigación Biomédica de Lleida. Fundación Dr. Pifarre (IRBLLEIDA)

Ana Martinez Bardaji, Instituto de Investigación Biomédica de Lleida. Fundación Dr. Pifarre (IRBLLEIDA)

Nuria Dolade Masot, Instituto de Investigación Biomédica de Lleida. Fundación Dr. Pifarre (IRBLLEIDA)

Aurora Pérez Gómez, Instituto de Investigación Biomédica de Lleida. Fundación Dr. Pifarre (IRBLLEIDA)

Auria Eritja Sanjuan, Instituto de Investigación Biomédica de Lleida. Fundación Dr. Pifarre (IRBLLEIDA)

Antonio Osuna Ortega, Hospital Universitario Virgen de las Nieves de Granada

Rosemary Wangensteen Fuentes, Universidad de Jaén

Maria del Carmen De Gracia Guindo, Hospital Universitario Virgen de las Nieves de Granada

Maria del Carmen Ruiz Fuentes, Hospital Universitario Virgen de las Nieves de Granada

Francisco O’Valle Ravassa, Universidad de Granada

Mercedes Caba Molina, Hospital Universitario San Cecilio

César Luis Ramírez Tortosa, Hospital Universitario San Cecilio

Raimundo García Del Moral Garrido, Universidad de Granada

María José Soler Romeo, Fundación Instituto de Investigación Valle de Hebrón

Conxita Jacobs-Cachá, Vall D’Hebron Research Institute (VHIR)

Oriol Bestard Matamoros, Vall D’Hebron Research Institute (VHIR)

Francesc Moreso Mateos, Vall D’Hebron Research Institute (VHIR)

María Antonia Emilia Meneghini, Vall D’Hebron Research Institute (VHIR)

Joana Sellares Roig, Hospital Universitari Vall D’Hebron

Irina Torres Betsabé, Hospital Universitari Vall D’Hebron

Carlos López Larrea, Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias. Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria del Principado de Asturias

Beatriz Suarez Álvarez, Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria del Principado de Asturias

María del Carmen Díaz Corte, Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias. Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria del Principado de Asturias

Raúl R Rodrigues-Diez, Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria del Principado de Asturias

Antonio López Vázquez, Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias. Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria del Principado de Asturias

Segundo González Rodríguez, Universidad de Oviedo

José Ramón Vidal Castiñeira, Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias. Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria del Principado de Asturias

Cristina Martín Martín, Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria del Principado de Asturias

María Laura Saiz Álvarez, Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria del Principado de Asturias

Viviana Corte Iglesias, Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria del Principado de Asturias

Jesús Martínez Borra, Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias. Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria del Principado de Asturias

María Auxiliadora Bajo Rubio, Hospital Universitario La Paz

Gloria Del Peso Gilsanz, Hospital Universitario La Paz

Manuel López Cabrera, Centro de Biología Molecular Severo Ochoa

José Antonio Jiménez Heffernan, Hospital Universitario La Princesa

Marta Ossorio González, Hospital Universitario La Paz

Olga Costero González, Hospital Universitario La Paz

María Elena González García, Hospital Universitario La Paz

Carlos Jiménez Martín, Hospital Universitario La Paz

Pilar Sandoval Correa, Centro de Biología Molecular Severo Ochoa

Sara Afonso Ramos, Hospital Universitario La Paz

María López Oliva, Hospital Universitario La Paz

Begoña Rivas Becerra, Hospital Universitario La Paz

Cristina Vega Cabrera, Hospital Universitario La Paz

Guadalupe Tirma González Mateo, Centro de Biología Molecular Severo Ochoa

Rafael Sánchez Villanueva, Hospital Universitario La Paz

Laura Álvarez García, Hospital Universitario La Paz

Jorge B Cannata Andía, Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias. Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria del Principado de Asturias

Manuel Naves Díaz, Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias. Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria del Principado de Asturias

José Luis Fernández Martín, Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias. Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria del Principado de Asturias

Natalia Carrillo López, Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria del Principado de Asturias

Sara Panizo García, Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria del Principado de Asturias

Cristina Alonso Montes, Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria del Principado de Asturias

Minerva Rodríguez García, Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias. Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria del Principado de Asturias

Iñigo Lozano Martínez Luengas, Hospital de Cabueñes

Emilio Sánchez Álvarez, Hospital de Cabueñes

Laura Martínez Arias, Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria del Principado de Asturias

Beatriz Martín Carro, Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria del Principado de Asturias

Julia Martín Virgala, Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria del Principado de Asturias

Miguel García González, Complejo Hospitalario de Santiago de Compostela (CHUS). Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria (IDIS)

José María Lamas Barreiro, Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Vigo

Miguel Pérez Fontan, Complejo Hospitalario Universitario A Coruña

Alfonso Otero González, Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Ourense

Luz María Cuiña Barja, Complejo Hospitalario de Pontevedra

Alejandro Sánchez Barreiro, Universidad de Santiago de Compostela

Beatriz Pazos Arias, Policlínico Vigo S.A.

Ángel Alonso Hernández, Complejo Hospitalario Universitario A Coruña

María Pardo Pérez, Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria de Santiago de Compostela (IDIS)

Jesús Calviño Varela, Hospital Lucus Augusti

Jorge Amigo Lechuga, Fundación Pública Gallega de Medicina Genómica

Cándido Díaz Rodríguez, Hospital Clínico Universitario de Santiago

María García Murias, Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria de Santiago de Compostela (IDIS)

Ana María Barcia de la Iglesia, Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria de Santiago de Compostela (IDIS)

Pablo Bouza Piñeiro, Complejo Hospitalario A. Marcide-Novoa Santos

Álvaro Gil González, Universidad de Santiago de Compostela

Adrian Cordido Eijo, Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria de Santiago de Compostela (IDIS)

Noa Carrera Cachaza, Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria de Santiago de Compostela (IDIS)

Marta Vizoso González, Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria de Santiago de Compostela (IDIS)

Josep Maria Cruzado Garrit, Hospital de Bellvitge

Núria Lloberas Blanch, Fundación Idibell

Ana Maria Sola Martínez, Fundación Idibell

Miguel Hueso Val, Hospital de Bellvitge

Juliana BordignonDraibe, Hospital de Bellvitge

Edoardo Melilli, Hospital de Bellvitge

Anna Manonelles Montero, Hospital de Bellvitge

Núria Montero Pérez, Hospital de Bellvitge

Xavier Fulladosa Oliveras, Hospital de Bellvitge

Marta Crespo Barrio, Instituto Hospital del Mar de Investigaciones Médicas (FIMIM)

Julio Pascual Santos, Instituto Hospital del Mar de Investigaciones Médicas (FIMIM)

Clara Barrios Barrera, Instituto Hospital del Mar de Investigaciones Médicas (FIMIM)

María José Pérez Sáez, Instituto Hospital del Mar de Investigaciones Médicas (FIMIM)

María Dolores Redondo Pachón, Instituto Hospital del Mar de Investigaciones Médicas (FIMIM)

Carlos Arias Cabrales, Instituto Hospital del Mar de Investigaciones Médicas (FIMIM)

Anna Buxeda Porras, Instituto Hospital del Mar de Investigaciones Médicas (FIMIM)

Eva Rodríguez García, Instituto Hospital del Mar de Investigaciones Médicas (FIMIM)

Laia Sans Atxer, Instituto Hospital del Mar de Investigaciones Médicas (FIMIM)

Vanesa Palau González, Instituto Hospital del Mar de Investigaciones Médicas (FIMIM)

Laura Llinàs Mallol, Instituto Hospital del Mar de Investigaciones Médicas (FIMIM)

Marta Riera Oliva, Instituto Hospital del Mar de Investigaciones Médicas (FIMIM)

Diego Rodríguez Puyol, Fundación Investigación Biomédica. Hospital Príncipe de Asturias

María Piedad Ruiz Torres, Universidad de Alcalá

Susana López Ongil, Fundación Investigación Biomédica. Hospital Príncipe de Asturias

Laura Calleros Basilio, Universidad de Alcalá

Gemma Olmos Centenera, Universidad de Alcalá

Patricia Martínez de Miguel, Hospital Universitario Príncipe de Asturias

Loreto Fernández Rodríguez, Hospital Universitario Príncipe de Asturias

Hanane Bouarich Nadah, Hospital Universitario Príncipe de Asturias

María Pérez Fernández, Hospital Universitario Príncipe de Asturias

Manuel Rafael Ramírez Chamond, Universidad de Alcalá

Patricia Sequera Ortiz, Hospital Universitario Infanta Leonor

Nuria García Fernández, Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria de Navarra (IDISNA),

Alberto Benito Boillos, Universidad de Navarra

Nerea Varo Cenarruzabeitia, Universidad de Navarra

María Asunción Fernández Seara, Universidad de Navarra

Inés Díaz Dorronsoro, Universidad de Navarra

Paloma Martin Moreno, Clínica Universidad de Navarra

Francisco Javier Lavilla, Clínica Universidad de Navarra

Armando Torres, Hospital Universitario de Canarias. Universidad de La Laguna

Domingo Marrero Miranda, Hospital Universitario de Canarias

Aurelio Pastor Rodríguez Hernández, Hospital Universitario de Canarias

Eduardo De Bonis Redondo, Hospital Universitario de Canarias

Esteban Porrini, Universidad de La Laguna

María de los Ángeles Cobo Caso, Hospital Universitario de Canarias

María Lourdes Pérez Tamajón, Hospital Universitario de Canarias

Margarita Rufino Hernández, Hospital Universitario de Canarias

María Sagrario García Rebollo, Hospital Universitario de Canarias

Patricia Delgado Mallen, Hospital Universitario de Canarias

Alejandra Álvarez González, Hospital Universitario de Canarias

Ana María González Rinne, Hospital Universitario de Canarias

Rosa Miquel Rodríguez, Hospital Universitario de Canarias

Sara Estupiñan Torres, Hospital Universitario de Canarias

Diego Álvarez Sosa, Hospital Universitario de Canarias

Beatriz Escamilla Cabrera, Hospital Universitario de Canarias

Nayara Zamora Rodríguez, Hospital Universitario de Canarias

Arminda Fariña Hernández, Hospital Universitario de Canarias

María José Rodríguez Gamboa, Hospital Universitario de Canarias

Cobo Caso, Maria de Los Angeles, Hospital Universitario de Canarias

PerezTamajon, Maria Lourdes, Hospital Universitario de Canarias

Rufino Hernandez, Margarita, Hospital Universitario de Canarias

Garcia Rebollo, Maria Sagrario, Hospital Universitario de Canarias

Delgado Mallen, Patricia, Hospital Universitario de Canarias

AlvarezGonzalez, Alejandra, Hospital Universitario de Canarias

Gonzalez Rinne, Ana Maria, Hospital Universitario de Canarias

Miquel Rodriguez, Rosa, Hospital Universitario de Canarias

Estupiñan Torres, Sara, Hospital Universitario de Canarias

Alvarez Sosa, Diego, Hospital Universitario de Canarias

Escamilla Cabrera, Beatriz, Hospital Universitario de Canarias

Zamora Rodiguez, Nayara, Hospital Universitario de Canarias

Fariña Hernandez, Arminda, Hospital Universitario de Canarias

Rodriguez Gamboa, MariaJose, Hospital Universitario de Canarias

María Laura García Bermejo, Instituto Ramón y Cajal de Investigación Sanitaria (IRYCIS)

Milagros Fernández Lucas, Hospital Ramón y Cajal

Elisa Conde Moreno, Instituto Ramón y Cajal de Investigación Sanitaria (IRYCIS)

Laura Salinas Muñoz, Instituto Ramón y Cajal de Investigación Sanitaria (IRYCIS)

Silvia Serrano Huertas, Instituto Ramón y Cajal de Investigación Sanitaria (IRYCIS)

Esperanza Macarena Rodríguez Serrano, Instituto Ramón y Cajal de Investigación Sanitaria (IRYCIS)

Miren Edurne Ramos Muñoz, Instituto Ramón y Cajal de Investigación Sanitaria (IRYCIS)

Lorena Crespo Toro, Instituto Ramón y Cajal de Investigación Sanitaria (IRYCIS)

Carolina Pilar Blanco Agudo, Instituto Ramón y Cajal de Investigación Sanitaria (IRYCIS)

Cristina Galeano Álvarez, Instituto Ramón y Cajal de Investigación Sanitaria (IRYCIS)

José Portoles, Fundación Investigación Biomédica Hospital Puerta de Hierro

María Marqués, Fundación Investigación Biomédica Hospital Puerta de Hierro

Esther Rubio, Fundación Investigación Biomédica Hospital Puerta de Hierro

Beatriz Sánchez-Sobrino, Fundación Investigación Biomédica Hospital Puerta de Hierro

Estefanya García-Menéndez, Fundación Investigación Biomédica Hospital Puerta de Hierro

Alberto Lázaro Fernández, Universidad Complutense de Madrid

Marian Goicoechea Diezhandin, IISGM. Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón

Patrocinio Rodríguez Benítez, IISGM. Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón

María Ángeles González-Nicolás González, Universidad Complutense de Madrid

Meritxell López Gallardo, Universidad Complutense de Madrid

Gema María Fernández Juárez, Hospital Universitario Fundación Alcorcón

Eduardo Gutiérrez Martínez, Instituto de Investigación Hospital 12 de Octubre (i+12)

Manuel Praga Terente, Instituto de Investigación Hospital 12 de Octubre (i+12)

Ana Tato Ribera, Hospital Universitario Fundación Alcorcón

Teresa Cavero Escribano, Instituto de Investigación Hospital 12 de Octubre (i+12)

Fernando Caravaca Fontan, Instituto de Investigación Hospital 12 de Octubre (i+12)

Amir Shabaka Fernández, Hospital Universitario Fundación Alcorcón

Nicolás Roberto Robles Pérez-Monteoliva, Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Badajoz

Enrique Luna Huerta, Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Badajoz

Guillermo Gervasini Rodríguez, Facultad de Medicina de Badajoz

Sergio Barroso Hernández, Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Badajoz

Sonia Mota Zamorano, Facultad de Medicina de Badajoz

Juan Manuel López Gómez, Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Badajoz

Román Hernández Gallego, Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Badajoz

Please see a list of the authors from these organizations that approve and support the manuscript in Appendix A.

AIRG-E: Asociación Información Enfermedades Renales Genéticas; EKPF: European Kidney Patients’ Federation; ALCER: Federación Nacional de Asociaciones para la Lucha Contra las Enfermedades del Riñón; FRIAT: Fundación Renal Íñigo Álvarez de Toledo; REDINREN: Red de Investigación Renal; RICORS2040: Resultados en Salud 2040; SENEFRO: Sociedad Española de Nefrología; SET: Sociedad Española de Trasplante; ONT: Organización Nacional de Trasplantes.