The ideal vascular access type for elderly hemodialysis (HD) patients remains debatable. The aim of this study was to analyze the association between patterns of vascular access use within the first year of HD and mortality in elderly patients.

MethodsSingle-center retrospective study of 99 incident HD patients aged≥80 years from January 2010 to May 2021. Patients were categorized according to their patterns of vascular access use within the first year of HD: central venous catheter (CVC) only, CVC to arteriovenous fistula (AVF), AVF to CVC, and AVF only. Baseline clinical data were compared among groups. Survival outcomes were analyzed using Kaplan–Meier survival curves and Cox's proportional hazards model.

ResultsWhen compared with CVC to AVF, mortality risk was significantly higher among CVC only patients and similar to AVF only group [HR 0.93 (95% CI 0.32–2.51)]. Ischemic heart disease [HR 1.74 (95% CI 1.02–2.96)], lower levels of albumin [HR 2.16 (95% CI 1.28–3.64)] and hemoglobin [HR 4.10(95% CI 1.69–9.92)], and higher levels of c-reactive protein [HR 1.87(95% CI 1.11–3.14)] were also associated with increased mortality risk in our cohort, p<0.05.

ConclusionOur findings suggested that placement of an AVF during the early stages of dialysis was associated with lower mortality compared to persistent CVC use among elderly patients. AVF placement appears to have a positive impact on survival outcomes, even in those who started dialysis with a CVC.

El tipo de acceso vascular ideal para pacientes ancianos en hemodiálisis (HD) sigue siendo discutible. El objetivo de este estudio fue analizar la asociación entre los patrones de uso del acceso vascular en el primer año de HD y la mortalidad en pacientes ancianos.

MétodosEstudio retrospectivo unicéntrico de 99 pacientes incidentes en HD con edades ≥80años desde enero de 2010 hasta mayo de 2021. Los pacientes fueron categorizados según sus patrones de uso del acceso vascular en el primer año de HD: catéter venoso central (CVC) solo, CVC a fístula arteriovenosa (FAV), FAV a CVC y FAV solamente. Los datos clínicos iniciales se compararon entre los grupos. Los resultados de supervivencia se analizaron mediante las curvas de supervivencia de Kaplan-Meier y el modelo de riesgo proporcional de Cox.

ResultadosEn comparación con el CVC para la FAV, el riesgo de mortalidad fue significativamente mayor entre los pacientes que solo recibieron CVC y similar al grupo que solo utilizó FAV (HR: 0,93; IC95%: 0,32-2,51). Cardiopatía isquémica (HR: 1,74; IC95%: 1,02-2,96), niveles más bajos de albúmina (HR: 2,16; IC 95%: 1,28-3,64) y de hemoglobina (HR: 4,10; IC 95%: 1,69-9,92), y niveles más altos de proteína C reactiva (HR: 1,87; IC 95%: 1,11-3,14) también se asociaron con un mayor riesgo de mortalidad en nuestra cohorte (p<0,05).

ConclusiónNuestros hallazgos sugirieron que la colocación de una FAV durante las primeras etapas de la diálisis se asoció con una menor mortalidad en comparación con el uso persistente de CVC en pacientes ancianos. La colocación de una FAV parece tener un impacto positivo en los resultados de supervivencia, incluso en aquellos que comenzaron la diálisis con un CVC.

The population of elderly patients with end-stage renal disease is growing worldwide. The 2019 Annual Report of the ERA-EDTA registry reported that 45% of the total prevalent European renal replacement therapy patients were aged≥65 years.1 The high prevalence of comorbidities, limited life expectancy and complex quality of life issues associated with this population pose unique challenges for clinicians, including choosing the ideal vascular access type for hemodialysis (HD).2–4 There is a wide debate about whether the “Fistula First” Initiative should be applied to elderly patients in HD, given lower maturation rates, longer maturation times and emerging data indicating the lack of a survival benefit of arteriovenous fistula (AVF) compared with central venous catheter (CVC) use in this group of patients.5,6 A new approach introduced by the KDOQI Clinical Practice Guideline for Vascular Access (2019) proposed an individualized and comprehensive map for dialysis modalities for the lifetime of the patient called the “ESKD Life-Plan,” achieved by creating a plan for each patient that considers the Patient's Life-Plan and corresponding Access Needs. This comprehensive patient-adjusted vascular access management plan throughout the period of end-stage renal disease, appears especially important in elderly patients.7 In fact, most elderly patients start dialysis with a CVC as their primary vascular access. A recent study suggested a lower mortality risk among elderly incident HD patients who had an AVF placed from a CVC in the early phases of dialysis, compared with those with persistent CVC use.8 The aim of our study was to analyze whether specific patterns of vascular access use within the first year of dialysis were associated with differential survival outcomes among a cohort of incident HD patients aged≥80 years.

Material and methodsWe conducted a single-center retrospective cohort study of incident HD patients at Centro Hospitalar do Médio Tejo, EPE HD unit between January 2010 and May 2021. All patients with ≥80 years were included. Patients who recovered renal function, lost follow-up, or switched to another renal replacement therapy were excluded. Patients were categorized according to their patterns of vascular access use within the first year of HD: CVC only, CVC to AVF, AVF only and AVF to CVC use.

The primary outcome was all-cause mortality, and secondary outcomes included laboratory data related to control of anemia, mineral bone disease and inflammatory markers, during the first year of treatment.

Baseline clinical and demographic characteristics, including age, gender, cause of end-stage renal disease, and previous nephrology follow-up were collected, as well as patient comorbidity score according to the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI, low<8 vs high≥8).

Laboratory parameters were measured at dialysis initiation and monthly during the first year of HD, including hemoglobin (Hgb), phosphorus (P+), calcium (Ca2+), albumin, c-reactive protein (CRP) and potassium (K+). Serum intact parathyroid hormone (iPTH) and ferritin were measured every 3 months.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 23.0 for Mac OS X. Continuous variables were presented as mean and standard deviation or median and interquartile range (IQR) for variables with skewed distributions. Nominal variables were presented as number (frequency) and percentage. A p value<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Baseline characteristics and laboratory data were compared among groups using the ANOVA test for normally distributed continuous variables (P+), Kruskal–Walli test for skewed distributed continuous variables (Hgb, Ca2+, albumin, CRP, K+, iPTH and ferritin) and Chi-square test for categorical variables.

The association between patterns of vascular access use within the first year of treatment and all-cause mortality risk were examined using standard survival analysis methods. Survival time was calculated from the date of dialysis initiation until the date of death or end of follow-up (May 31, 2021). Kaplan-Meier curves were developed for each group and compared by log-rank tests. Univariate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for all-cause mortality were estimated using the Cox proportional hazards risk model.

ResultsNinety-nine patients aged≥80 years were recruited into the study: 48 (48.5%) were male, 44 (44.4%) diabetic, 60 (60.6%) had ischemic heart disease and 15 (15.2%) peripheral artery disease. Mean CCI was 8.41±1.65. Mean age was 85.1±3.9 years and eleven patients (11.1%) were over 90 years old. Seventy-four patients (75.8%) started dialysis with a CVC. Over the first year of dialysis, we observed that 56.6% (n=56) of patients persisted in CVC use only, 19.2% (n=19) underwent placement of an AVF from a CVC, 13.1% (n=13) persisted in AVF use only and 11.1% (n=11) underwent placement of a CVC from an AVF. The duration of CVC use was 219.5±100.6 days in the CVC to AVF group and 295.4±107.4 days in the AVF to CVC group.

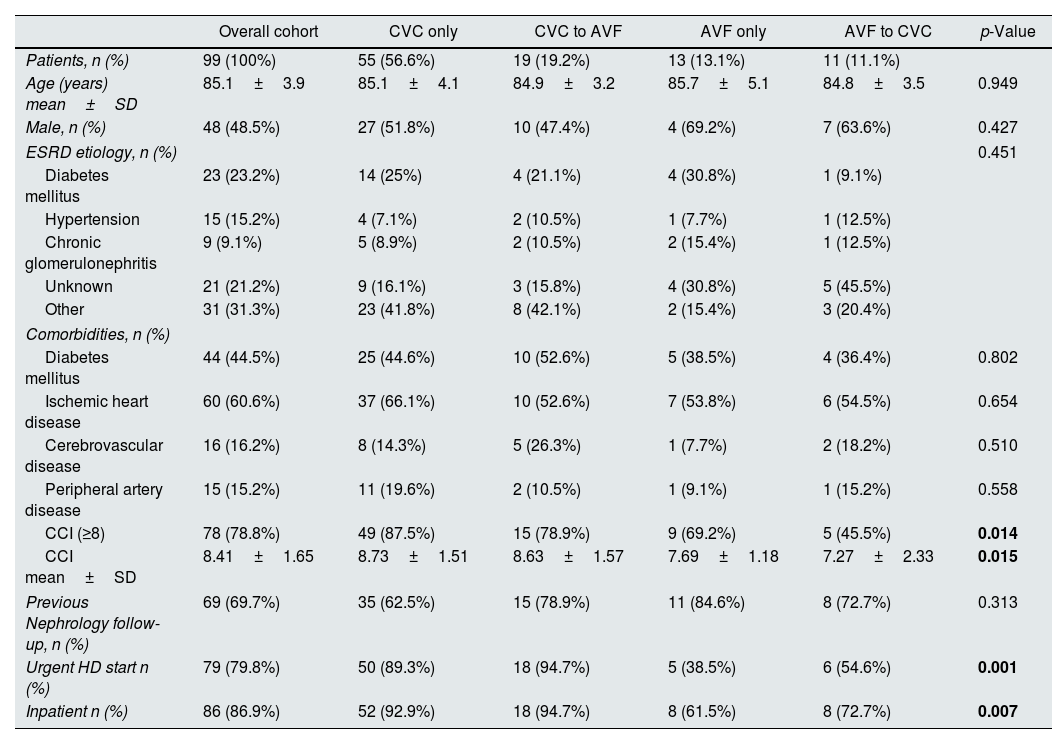

No statistically significant differences were found in age, gender, or cause of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) among groups. Compared with other patients, those who persisted on having a CVC only were more likely to initiate dialysis with urgent criteria, as inpatients and to have CCI≥8 (Table 1).

Baseline patient characteristics stratified by patterns of vascular access type during the first year of dialysis.

| Overall cohort | CVC only | CVC to AVF | AVF only | AVF to CVC | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, n (%) | 99 (100%) | 55 (56.6%) | 19 (19.2%) | 13 (13.1%) | 11 (11.1%) | |

| Age (years) mean±SD | 85.1±3.9 | 85.1±4.1 | 84.9±3.2 | 85.7±5.1 | 84.8±3.5 | 0.949 |

| Male, n (%) | 48 (48.5%) | 27 (51.8%) | 10 (47.4%) | 4 (69.2%) | 7 (63.6%) | 0.427 |

| ESRD etiology, n (%) | 0.451 | |||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 23 (23.2%) | 14 (25%) | 4 (21.1%) | 4 (30.8%) | 1 (9.1%) | |

| Hypertension | 15 (15.2%) | 4 (7.1%) | 2 (10.5%) | 1 (7.7%) | 1 (12.5%) | |

| Chronic glomerulonephritis | 9 (9.1%) | 5 (8.9%) | 2 (10.5%) | 2 (15.4%) | 1 (12.5%) | |

| Unknown | 21 (21.2%) | 9 (16.1%) | 3 (15.8%) | 4 (30.8%) | 5 (45.5%) | |

| Other | 31 (31.3%) | 23 (41.8%) | 8 (42.1%) | 2 (15.4%) | 3 (20.4%) | |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | ||||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 44 (44.5%) | 25 (44.6%) | 10 (52.6%) | 5 (38.5%) | 4 (36.4%) | 0.802 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 60 (60.6%) | 37 (66.1%) | 10 (52.6%) | 7 (53.8%) | 6 (54.5%) | 0.654 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 16 (16.2%) | 8 (14.3%) | 5 (26.3%) | 1 (7.7%) | 2 (18.2%) | 0.510 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 15 (15.2%) | 11 (19.6%) | 2 (10.5%) | 1 (9.1%) | 1 (15.2%) | 0.558 |

| CCI (≥8) | 78 (78.8%) | 49 (87.5%) | 15 (78.9%) | 9 (69.2%) | 5 (45.5%) | 0.014 |

| CCI mean±SD | 8.41±1.65 | 8.73±1.51 | 8.63±1.57 | 7.69±1.18 | 7.27±2.33 | 0.015 |

| Previous Nephrology follow-up, n (%) | 69 (69.7%) | 35 (62.5%) | 15 (78.9%) | 11 (84.6%) | 8 (72.7%) | 0.313 |

| Urgent HD start n (%) | 79 (79.8%) | 50 (89.3%) | 18 (94.7%) | 5 (38.5%) | 6 (54.6%) | 0.001 |

| Inpatient n (%) | 86 (86.9%) | 52 (92.9%) | 18 (94.7%) | 8 (61.5%) | 8 (72.7%) | 0.007 |

p-Values represent an ANOVA test for continuous variables and Chi-square test for categorical variables.

ESRD, end-stage renal disease; Hgb, hemoglobin; SD, standard deviation; IQR, interquartile range. In bold values with statistical significance.

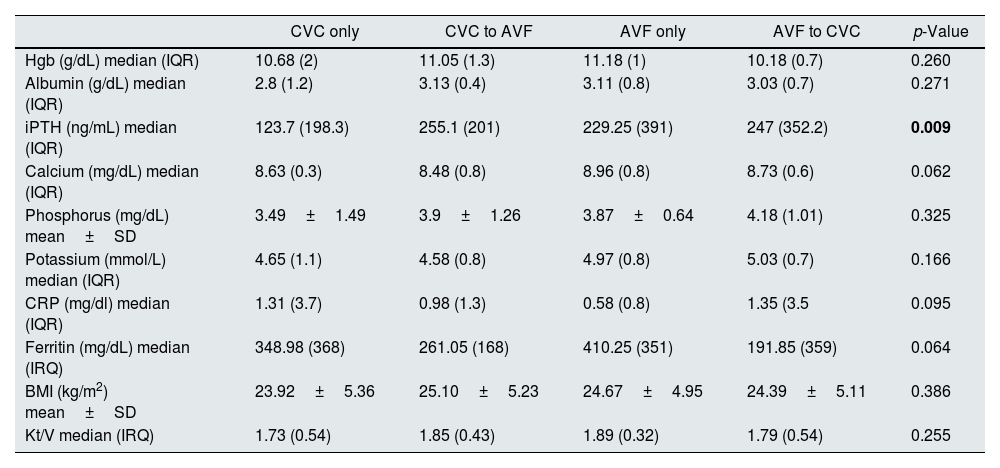

Laboratory data related to ESRD complications (anemia and mineral bone disease), nutrition and inflammation parameters in the first year of HD were similar among groups, except for iPTH which was significantly lower in the CVC only group (p<0.05). Hemodialysis efficacy (spKT/V) was also similar (Table 2).

Clinical and analytical outcomes stratified by patterns of vascular access type during the first year of dialysis.

| CVC only | CVC to AVF | AVF only | AVF to CVC | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hgb (g/dL) median (IQR) | 10.68 (2) | 11.05 (1.3) | 11.18 (1) | 10.18 (0.7) | 0.260 |

| Albumin (g/dL) median (IQR) | 2.8 (1.2) | 3.13 (0.4) | 3.11 (0.8) | 3.03 (0.7) | 0.271 |

| iPTH (ng/mL) median (IQR) | 123.7 (198.3) | 255.1 (201) | 229.25 (391) | 247 (352.2) | 0.009 |

| Calcium (mg/dL) median (IQR) | 8.63 (0.3) | 8.48 (0.8) | 8.96 (0.8) | 8.73 (0.6) | 0.062 |

| Phosphorus (mg/dL) mean±SD | 3.49±1.49 | 3.9±1.26 | 3.87±0.64 | 4.18 (1.01) | 0.325 |

| Potassium (mmol/L) median (IQR) | 4.65 (1.1) | 4.58 (0.8) | 4.97 (0.8) | 5.03 (0.7) | 0.166 |

| CRP (mg/dl) median (IQR) | 1.31 (3.7) | 0.98 (1.3) | 0.58 (0.8) | 1.35 (3.5 | 0.095 |

| Ferritin (mg/dL) median (IRQ) | 348.98 (368) | 261.05 (168) | 410.25 (351) | 191.85 (359) | 0.064 |

| BMI (kg/m2) mean±SD | 23.92±5.36 | 25.10±5.23 | 24.67±4.95 | 24.39±5.11 | 0.386 |

| Kt/V median (IRQ) | 1.73 (0.54) | 1.85 (0.43) | 1.89 (0.32) | 1.79 (0.54) | 0.255 |

p-Values represent an ANOVA test for normally distributed continuous variables (phosphorus) and a Kruskal–Wallis test for skewed distributed continuous variables.

Hgb, hemoglobin; SD, standard deviation; IQR, interquartile range; iPTH, intact parathormone; CRP, c-reactive protein. In bold values with statistical significance.

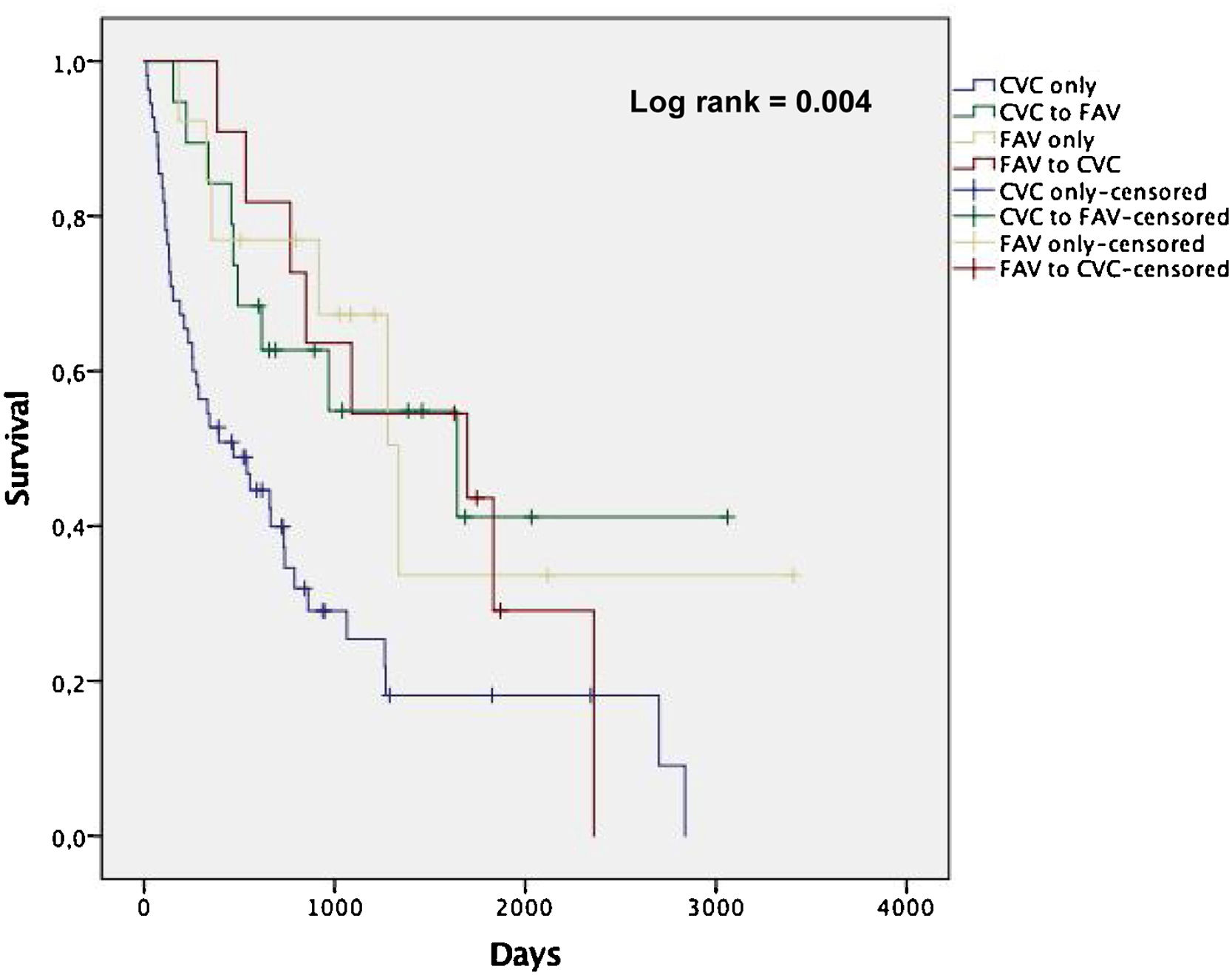

Among the patients enrolled in the study, there were 64 deaths over a follow-up period of 228 person-years. The mean follow-up was 2.3 years. The overall mortality rates by pattern of vascular access use within the first year of dialysis were 42.3, 17.4, 15.1 and 19.8 per 100 person-years for CVC only, CVC to AVF, AVF only and AVF to CVC, respectively. Fig. 1 shows non-adjusted Kaplan-Meier curves for all-cause death according to groups stratified by vascular access type. Patients in CVC only group showed a higher incidence rate of all-cause death compared with the other groups (log-rank test, p<0.05).

The mean and median survival times (in days) revealed a statistically significant disadvantage of CVC only group (p<0.05), demonstrating that the observed difference in survival curves was not due to chance. CVC to AVF patients showed a similar mean and median survival times as AVF only (Table 3). Among the CVC only patients, the rate of CVC-related bloodstream infection was 0.6 per 1000 days of CVC and infection-related mortality was 10.3 per 100 person-years (24.4% of all deaths in this group).

Confidence intervals mean and median for survival time (in days) according to patterns of vascular access type during the first year of dialysis.

| Groups | Mean | Median | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | Std. error | 95% confidence interval | Estimate | Std. error | 95% confidence interval | |||

| Lower bound | Upper bound | Lower bound | Upper bound | |||||

| CVC only | 939.944 | 162.708 | 621.037 | 1258.851 | 469.000 | 182.476 | 111.347 | 826.653 |

| CVC to AVF | 1708.427 | 316.036 | 1088.996 | 2327.859 | 1642.000 | 713.790 | 242.971 | 3042.029 |

| AVF only | 1740.663 | 436.323 | 885.471 | 2595.856 | 1692.000 | 654.570 | 413.043 | 2978.957 |

| AVF to CVC | 1467.109 | 240.123 | 996.467 | 1937.751 | 1335.000 | 225.462 | 893.094 | 1776.906 |

| Overall | 1268.743 | 137.320 | 999.596 | 1537.890 | 789.000 | 136.923 | 520.630 | 1057.370 |

CVC, central venous catheter; AVF, arteriovenous fistula.

Using the univariate Cox model, we compared patients with persistent CVC use to those with placement of an AVF from a CVC [HR 0.42 (95% CI 0.21–0.87)] and AVF only [HR 0.38 (95% CI 0.16–0.89)] with both groups showing a lower mortality risk (p<0.05). Those with placement of a CVC from an AVF also showed a trend towards lower mortality risk [HR 0.49 (95% CI 0.23–1.07)], although it was not statistically significant (p>0.05) (Table 4). When the reference group was changed to patients with placement of an AVF from a CVC, those with AVF use only showed a similar mortality risk [HR 0.93 (95% CI 0.32–2.51)]. By using univariate Cox proportional hazards regression, we found that other significant risk factors for all-cause mortality among these patients were ischemic heart disease [HR 1.74 (95% CI 1.02–2.96)], lower albumin (<3g/dL) [HR 2.16 (95% CI 1.28–3.64)], lower Hgb (<8.5g/dL) [HR 4.10(95% CI 1.69–9.92)] and higher CRP (>2.5mg/dL) [HR 1.87(95% CI 1.11–3.14)]. In the multivariable Cox regression model, after adjustment for these risk factors (albumin<3g/dL, Hgb<8.5g/dL and CRP<2.5mg/dL), mortality risk remained higher in the CVC group when compared with those with AVF only [HR 0.40(95% CI 0.19–0.83)] (p<0.05). The same trend was observed among those with placement of an AVF from a CVC [HR 0.51(95% CI 0.26–1.03)] and CVC from an AVF [HR 0.71(95% CI 0.41–1.24)] but did not reach statistical significance (p>0.05) (Table 4).

Association between patterns of vascular access type during the first year of dialysis and the risk of all-cause mortality examined by Cox proportional hazard models.

| Groups | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysisa | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% confidence interval | p-Value | HR | 95% confidence interval | p-Value | |

| CVC only | Reference | Reference | ||||

| CVC to AVF | 0.42 | 0.21–0.87 | 0.020 | 0.51 | 0.26–1.03 | 0.063 |

| AVF only | 0.38 | 0.16–0.89 | 0.030 | 0.40 | 0.19–0.83 | 0.013 |

| AVF to CVC | 0.49 | 0.23–1.07 | 0.080 | 0.71 | 0.41–1.24 | 0.230 |

| Isquemic heart disease | 1.74 | 1.02–2.96 | 0.036 | |||

| Albumin (<3g/dL) | 2.16 | 1.28–3.64 | 0.005 | |||

| CRP (>2.5mg/dL) | 1.87 | 1.11–3.14 | 0.023 | |||

| Hgb (<8.5g/dL) | 4.10 | 1.69–9.92 | 0.007 | |||

CVC, central venous catheter; AVF, arteriovenous fistula; CRP, c-reactive protein; Hgb, hemoglobin.

The use of CVCs among incident HD patients remains high, particularly in older patients (>80 years of age). In addition, a large proportion of patients who initiate treatment with a CVC do not switch to a permanent vascular access.8 Among those who make the transition, only a minority develop a functional AVF.8 Successful creation of an AVF requires suitable vasculature. Vein distensibility may be affected by a greater prevalence of peripheral vascular disease among elderly, which is supported by the greater risk of AVF failure found in this population.9,10 Moreover, several aspects of CVCs, including immediate readiness for use and the absence of pain with cannulation may make this an appealing vascular access option among elderly HD patients with limited life expectancy.11 In our study, most patients (75.8%) started dialysis with a CVC. Compared with other patients, those who started with a CVC were more likely to initiate dialysis as inpatients by urgent criteria, despite similar predialysis follow-up. Elderly patients are particularly susceptible to the development of acute kidney injury due to structural and functional deterioration of the kidneys, decreased renal reserve and the presence of comorbidities, reducing the ability to recover.12 Thus, elderly patients may present with urgent indications for dialysis prior to placement and maturation of an AVF, contributing to the high incidence of CVC use at dialysis initiation in this population.13–15 On the other hand, older patients lose kidney function at lower rates than younger ones, have a shorter survival due to competing risks of mortality and may be more likely to die before benefiting from an AVF.16–18 Furthermore, they may be more likely to experience primary AVF failure witch also increases the incidence of CVCs, morbidity, and mortality in this group.19 Therefore, we aimed to determine whether placement of an AVF from a CVC during the first year of dialysis was associated with better survival outcomes when compared to persistent CVC use in patients aged≥80 years. Among our cohort, compared with patients with persistent CVC use, those with AVF use only and placement of an AVF from a CVC had lower all-cause mortality risk. When the reference group was changed to patients with placement of an AVF from a CVC, those with AVF use only showed similar mortality risk. Our findings corroborate the results of Ko et al., suggesting a positive impact on survival outcomes associated with AVF placement in elderly, even in those who started dialysis with a CVC.8 In this population the presence of isquemic heart disease, lower levels of albumin (<3g/dL) and Hgb (<8.5g/dL) and higher levels of CRP (>2.5mg/dL) were also associated with increased mortality risk. Yeh et al. described similar results, identifying hypoalbuminemia and high CRP as mortality risk factors in elderly HD patients,20 suggesting an important role of inflammatory status in survival outcomes in this population.21,22 Indeed, recent observational studies have suggested that elderly patient characteristics account for a large fraction of the excess mortality associated with CVC use in this population.23,24 Although we cannot totally exclude this assumption, in our study, persistent CVC use was an independent mortality risk factor, even in models adjusted to patients’ characteristics, such as hypoalbuminemia, anemia and high inflammatory markers. Our findings suggest that placement of an AVF from a CVC during the early phases of dialysis is associated with lower mortality compared to persistent CVC use and similar mortality compared to AVF use only, among incident HD patients aged≥80years. Despite our results, a pragmatic patient-centered approach is mandatory, considering the possibility that the ‘AVF first’ approach should not be an absolute for all patients. There were some limitations in this study. First, this was a retrospective study with a small sample size. Second, this is not a randomized study and biases may exist as patients with worst general condition tend to receive HD via CVC. Third, the patient number were different among groups. Fourth, the study reflects the elderly population of a hospital HD unit.

- -

The high prevalence of comorbidities, limited life expectancy and complex quality of life issues pose unique challenges, including choosing the ideal vascular access type for HD in elderly patients.

- -

Our findings suggest that placement of an AVF from a CVC during the early phases of dialysis is associated with lower mortality compared to persistent CVC use and similar mortality compared to AVF use only, among incident HD patients aged≥80years.

- -

A pragmatic patient-centered approach is mandatory, considering the possibility that the ‘AVF first’ approach should not be an absolute for all patients.

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interestNo conflict of interest.