Despite the recommendations of the clinical guidelines, the percentage of central venous catheters (CVC) continues to be above the recommended standards. We do not know whether the increasing use of catheters is due to unavoidable or avoidable factors and, in the latter case, it would be in our power to modify these results.

The aim of this study was to analyze the causes that condition the use of CVC in a prevalent hemodialysis (HD) population in order to identify those modifiable factors on which to act in order to achieve the objectives of the guidelines.

MethodsRetrospective, descriptive and observational study in all prevalent patients on chronic hemodialysis belonging to 7 hemodialysis centers in Madrid, Castilla-León and Galicia in a cross-sectional study carried out in June 2021 (637 patients). The following were analyzed: age, sex, nationality, etiology of CKD, the vascular access with which they started hemodialysis, the number of previous failed arteriovenous fistulas (AVF), time since the start of HD, time since the placement of the CVC for the first time, the situation with respect to surgery and the causes of being a CVC carrier. In patients whose cause was refusal to undergo AVF, patients were asked about the cause of the refusal by directed questioning.

ResultsOf the 637 patients studied, 255 (40%) had a CVC, 346 had an AVF (54.3%) and 36 (5.7%) had a prosthesis. Of the 255 patients with CVC, 20.4% (52 p) were awaiting vascular access (AVF/prosthesis), 10.2% (26 p) had an AVF but could not be used and 69.4% (177 p) were not considered candidates for surgery (due to vascular surgery (16.9%; 43 pac), nephrology (16.5%, 42 pac) and patient refusal (36%; 92 pac). The most frequent cause for refusal of AVF was fear and patient preference. One of the most important factors associated with CVC use in prevalent patients was having started hemodialysis with a CVC. The greatest use of CVC at the start of HD was significantly associated with having more than one AVF performed, or starting HD urgently and not having been followed up and evaluated in the ACKD consultation.

ConclusionsThere is a high percentage of patients with a central venous catheter due to modifiable causes, which makes it necessary to systematically evaluate the process of creating AVF in order to enhance the planning, creation and maintenance of vascular access from the ACKD clinic, and to achieve the objective of the guidelines.

A pesar de las recomendaciones de las guías clínicas, el porcentaje de catéteres venosos centrales (CVC) sigue estando por encima de los estándares recomendados. Desconocemos si la utilización creciente de catéteres tiene su origen en factores inevitables o evitables y, en este último caso, estaría en nuestra mano modificar estos resultados.

El objetivo de este estudio ha sido analizar las causas que condicionan el uso de CVC en una población prevalente en hemodiálisis (HD)con el fin de identificar aquellos factores modificables sobre los que actuar para conseguir los objetivos de las guías.

MétodosEstudio retrospectivo, descriptivo y observacional en el total de pacientes prevalentes en hemodiálisis crónica pertenecientes a 7 centros de hemodiálisis extrahospitalarios de Madrid, Castilla-León y Galicia en un corte transversal realizado en junio 2021 (637 pacientes). Se analizan: edad, sexo, nacionalidad, etiología de la ERC, el acceso vascular con el que iniciaron hemodiálisis, el número de Fístulas arteriovenosas (FAV) previas fallidas, tiempo desde el inicio de la HD, tiempo desde la colocación del CVC por primera vez, la situación respecto a la cirugía y las causas de ser portador de CVC. En los pacientes cuya causa fue la negativa a realizarse una FAV se preguntó a los pacientes por la causa de la misma mediante interrogatorio dirigido.

ResultadosDe los 637 pacientes estudiados, 255 (40%) eran portadores de CVC, 346 portadores de FAV (54,3%) y 36 (5,7%) llevaban una prótesis. De los 255 pacientes portadores de CVC, el 20,4% ( 52 p) estaba pendiente de realización del acceso vascular (FAV/ prótesis), un 10,2% (26 p) tenían la FAV realizada pero no se podía utilizar y un 69,4% (177 p) no se consideraron candidatos a cirugía (por cirugía vascular (16,9%; 43 pac), por nefrología (16,5%, 42 pac) y por negativa del paciente(36%; 92 pac). La causa más frecuente para la negativa a la FAV fue el miedo y las preferencias de los pacientes. Uno de los factores más importantes asociados al uso de CVC en pacientes prevalentes fue haber iniciado hemodiálisis mediante un CVC. El mayor uso de CVC al inicio de HD se asoció significativamente con tener más de una FAV realizada, o iniciar HD de manera urgente y no haber sido seguido y evaluado en la consulta de ERCA.

ConclusionesExiste un elevado porcentaje de pacientes con catéter venoso central por causas modificables que hace necesaria la evaluación sistemática del proceso de creación de FAV para potenciar la planificación, creación y mantenimiento del acceso vascular desde la consulta de ERCA, y alcanzar el objetivo de las guías.

The increase in the percentage of central venous catheters (CVC) for haemodialysis (HD) over the years is not new1 and is observed in many different centres, regions and countries.2–4

Since the 1990s, clinical guidelines have advocated for the placement of an arteriovenous fistula (AVF) whenever possible in patients on HD.5 The Spanish vascular access (VA) for HD guidelines for published in 2017 set a goal standard of <20% for CVC and >75% for AVF in prevalent patients.6 In contrast, the most recent Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (KDOQI) VA guidelines from 20197 propose a patient-centred approach and the need to provide more personalised care, incorporating patient goals and preferences with adequate information about the complications associated with each preference, while also maintaining best practices for quality and safety taking into account the characteristics of each patient,8–10 but still advocate fora CVC target of less than 10% for prevalent HD patients.

This is based on better survival, lower economic costs and less complications in patients with AVF compared to CVC.11 Despite broad acceptance of AVF as the VA of choice, an emerging body of literature suggests that the better survival of AVF patients may be due to better previous health status.12,13

Despite best efforts and recommendations, fulfilling these objectives lags behind expectations and the data show that VA is an issue that remains unresolved.14

In light of this situation, we set out to analyse whether the origin of the increasing use of catheters lies in avoidable factors, such as inadequate planning or preferences of the physician or the patient, or in unavoidable factors, such as a change in the characteristics of the haemodialysis population, which is increasingly older and comorbid, and we sought to determine whether the standards proposed by the guidelines are achievable or beyond our control.

The aim of this study was to perform a critical analysis about causes of the CVC use in a prevalent haemodialysis population in order to identify modifiable factors on which to act to to achieve the objectives of the guidelines.

Material and methodsStudy designThis is a retrospective, descriptive, observational and cross-sectional study of all prevalent patients on chronic haemodialysis from seven haemodialysis centres located outside hospitals in the regions of Madrid, Castille - León and Galicia conducted in June 2021. The study population included637 haemodialysis patients as of 30 June 2021. Patients were referred to the haemodialysis centre from the referral hospital. Both the creation of the first venous access and subsequent venous access depended on the surgery department of the referral hospital. If a patient arrived at the centre with a CVC, it was assessed and referred to the Vascular Surgery Department of the referral hospital, either directly or through the Nephrology Department.

All centres had a common protocol for VA monitoring and surveillance daily with first-generation methods and with second-generation methods quarterly using dilution screening methods to calculate periodic measurement of AVF blood flow (Qa) and Doppler ultrasound.

VariablesThe following variables were collected: age, gender, nationality, dialysis centre, region, aetiology of chronic kidney disease (CKD), AVF and prosthesis thrombosis rate, the VA with which the patient started HD, the number of previous failed AVF, time since starting HD, time since first CVC placement, surgical status and the reasons for having a CVC. In patients whose reason was refusal to have an AVF, patients were asked directed questions about why they had refused.

Statistical analysisFor statistical analysis, Pearson's χ2 test was used for categorical variables, Student's t-test (parametric) or Mann-Whitney U-test (non-parametric) for continuous variables, or one-way ANOVA for multiple comparisons. Normality of distribution was verified by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Continuous variables were expressed as mean (standard deviation) or median (interquartile range), as appropriate. Categorical variables were reported as numbers (percentage). Correlation was studied using Pearson's correlation coefficient. All p-values were two-tailed. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

ResultsOf the 637 patients analyzed, 255 (40%) had a CVC, 346 (54.3%) had an AVF and 36 (5.7%) had a prosthesis. The mean age was 66.4 ± 15.4 years, 65% were male and 10% were of non-Spanish nationality. The aetiology of CKD was diabetic nephropathy in 27.5%, not recorded in 23.1%, glomerular in 15.2%, tubulointerstitial nephropathy in 8%, polycystic kidney in 5.7%, vascular in 11% and other in 9.4%.

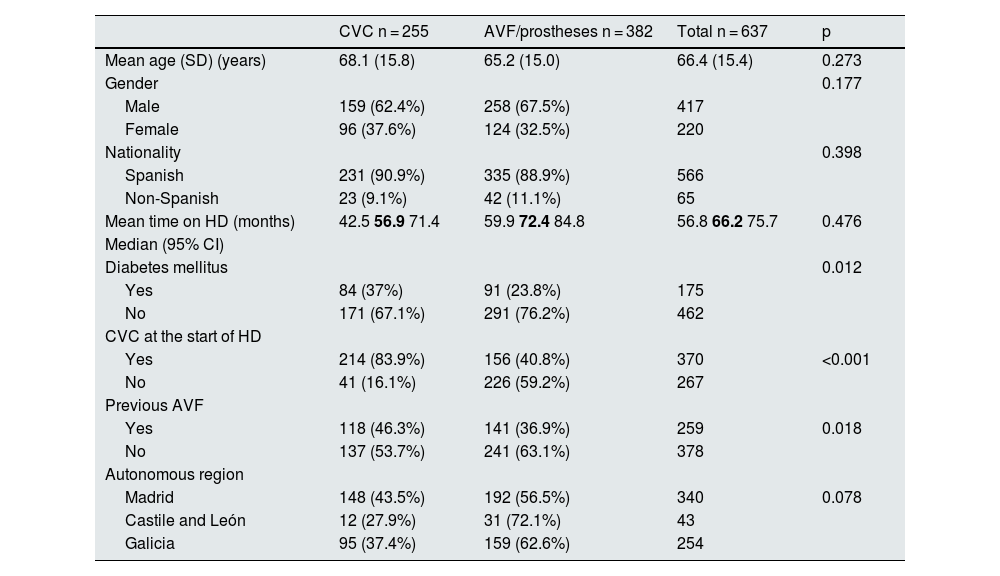

Factors associated with the use of CVC use in prevalent patientsDemographic characteristics and factors associated with CVC use in prevalent patients are shown in Table 1; Factors associated with CVC use are having started haemodialysis with a CVC (83.9% of prevalent patients with a CVC vs 40.8% of prevalent patients with an AVF/prosthesis [p < 0.001]). There were no significant differences in age, gender, nationality, or time on haemodialysis among prevalent CVC patients.

Demographic characteristics and factors associated with the use of central venous catheters in prevalent patients.

| CVC n = 255 | AVF/prostheses n = 382 | Total n = 637 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (SD) (years) | 68.1 (15.8) | 65.2 (15.0) | 66.4 (15.4) | 0.273 |

| Gender | 0.177 | |||

| Male | 159 (62.4%) | 258 (67.5%) | 417 | |

| Female | 96 (37.6%) | 124 (32.5%) | 220 | |

| Nationality | 0.398 | |||

| Spanish | 231 (90.9%) | 335 (88.9%) | 566 | |

| Non-Spanish | 23 (9.1%) | 42 (11.1%) | 65 | |

| Mean time on HD (months) | 42.5 56.9 71.4 | 59.9 72.4 84.8 | 56.8 66.2 75.7 | 0.476 |

| Median (95% CI) | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.012 | |||

| Yes | 84 (37%) | 91 (23.8%) | 175 | |

| No | 171 (67.1%) | 291 (76.2%) | 462 | |

| CVC at the start of HD | ||||

| Yes | 214 (83.9%) | 156 (40.8%) | 370 | <0.001 |

| No | 41 (16.1%) | 226 (59.2%) | 267 | |

| Previous AVF | ||||

| Yes | 118 (46.3%) | 141 (36.9%) | 259 | 0.018 |

| No | 137 (53.7%) | 241 (63.1%) | 378 | |

| Autonomous region | ||||

| Madrid | 148 (43.5%) | 192 (56.5%) | 340 | 0.078 |

| Castile and León | 12 (27.9%) | 31 (72.1%) | 43 | |

| Galicia | 95 (37.4%) | 159 (62.6%) | 254 |

AVF: arteriovenous fistula; CVC: central venous catheter; HD: haemodialysis; SD: standard deviation; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval.

The CI figures are shown in roman type and the median in bold.

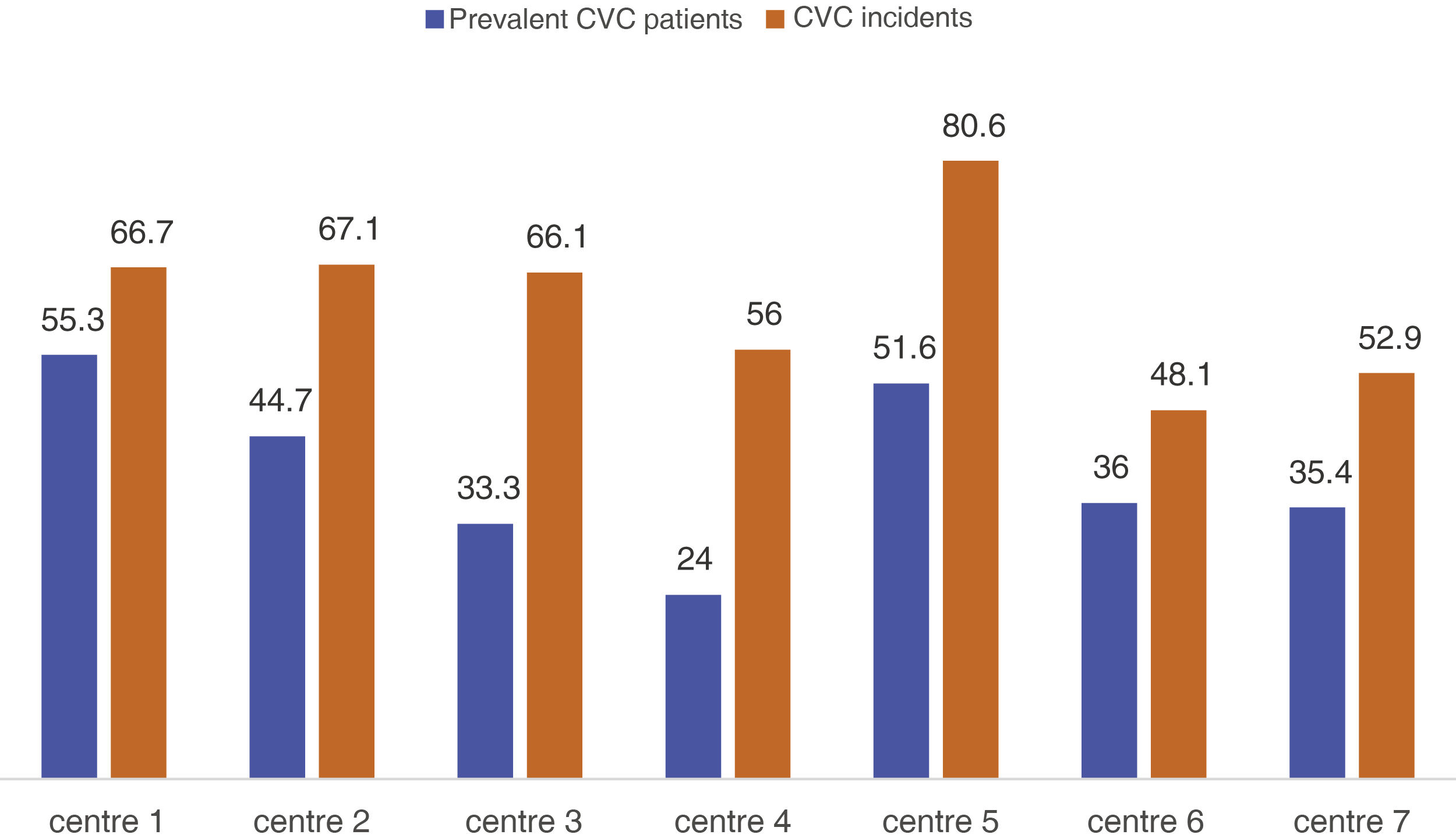

There were no significant differences between the Spain's regions (Table 1), but significant differences were found in relation to the referral hospital and centre (p = 0.004) (Fig. 1). The average autologous fistula thrombosis rate was 0.04 and the average prosthesis thrombosis rate was 0.22 across centres. No significant differences were found in the rate of thrombosis either by centre or by autonomous region (p = 0.076).

There was a positive correlation between starting HD with CVC and maintaining CVC thereafter (r: 0.41; p < 0.001).

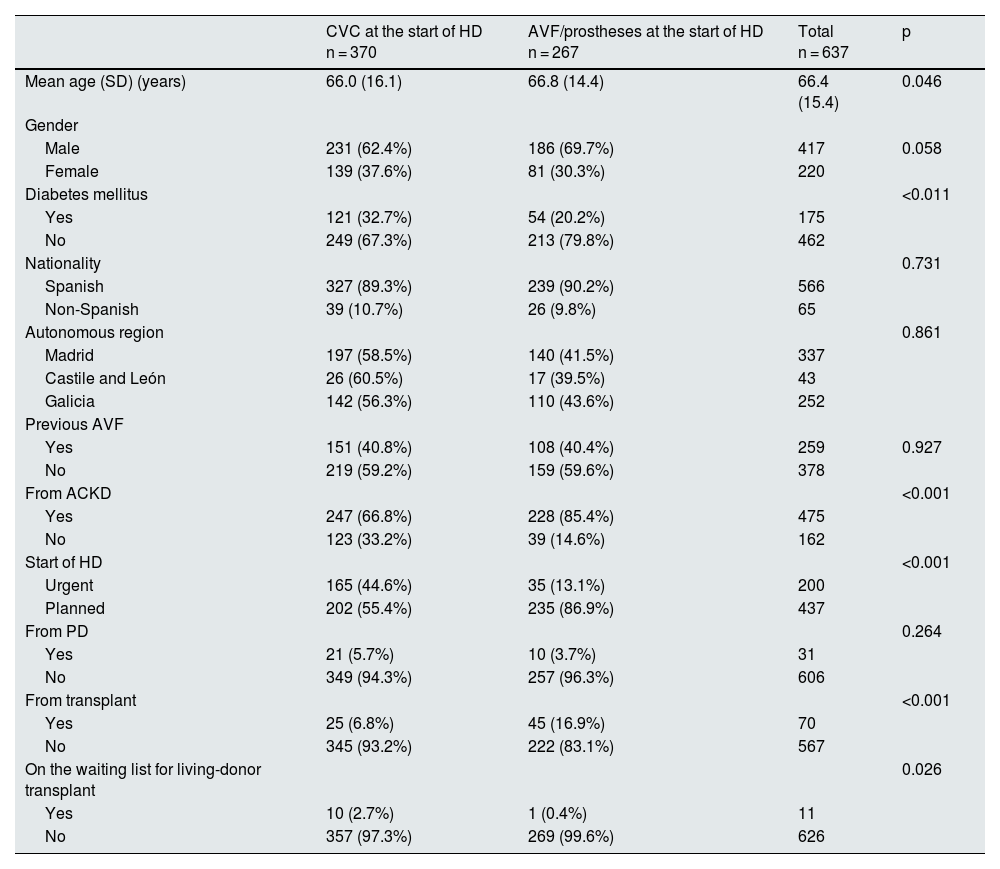

Factors associated with the use of CVC at the start of haemodialysisStarting HD via CVC was significantly associated with an urgent initiation of HD and not having been followed and assessed in the advanced chronic kidney disease (ACKD) clinic (Table 2). No statistically significant differences were found in the use of CVC between patients who had been using them for more than six months (149/450; 33.1%) versus those using the CVC for less than six months (12/25; 48%); p = 0.303. Transplant recipients and those on the waiting list for living-donor transplant had a higher risk of starting HD with CVC.

Factors associated with the use of central venous catheters at the start of HD.

| CVC at the start of HD n = 370 | AVF/prostheses at the start of HD n = 267 | Total n = 637 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (SD) (years) | 66.0 (16.1) | 66.8 (14.4) | 66.4 (15.4) | 0.046 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 231 (62.4%) | 186 (69.7%) | 417 | 0.058 |

| Female | 139 (37.6%) | 81 (30.3%) | 220 | |

| Diabetes mellitus | <0.011 | |||

| Yes | 121 (32.7%) | 54 (20.2%) | 175 | |

| No | 249 (67.3%) | 213 (79.8%) | 462 | |

| Nationality | 0.731 | |||

| Spanish | 327 (89.3%) | 239 (90.2%) | 566 | |

| Non-Spanish | 39 (10.7%) | 26 (9.8%) | 65 | |

| Autonomous region | 0.861 | |||

| Madrid | 197 (58.5%) | 140 (41.5%) | 337 | |

| Castile and León | 26 (60.5%) | 17 (39.5%) | 43 | |

| Galicia | 142 (56.3%) | 110 (43.6%) | 252 | |

| Previous AVF | ||||

| Yes | 151 (40.8%) | 108 (40.4%) | 259 | 0.927 |

| No | 219 (59.2%) | 159 (59.6%) | 378 | |

| From ACKD | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 247 (66.8%) | 228 (85.4%) | 475 | |

| No | 123 (33.2%) | 39 (14.6%) | 162 | |

| Start of HD | <0.001 | |||

| Urgent | 165 (44.6%) | 35 (13.1%) | 200 | |

| Planned | 202 (55.4%) | 235 (86.9%) | 437 | |

| From PD | 0.264 | |||

| Yes | 21 (5.7%) | 10 (3.7%) | 31 | |

| No | 349 (94.3%) | 257 (96.3%) | 606 | |

| From transplant | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 25 (6.8%) | 45 (16.9%) | 70 | |

| No | 345 (93.2%) | 222 (83.1%) | 567 | |

| On the waiting list for living-donor transplant | 0.026 | |||

| Yes | 10 (2.7%) | 1 (0.4%) | 11 | |

| No | 357 (97.3%) | 269 (99.6%) | 626 |

ACKD: advanced chronic kidney disease; AVF: arteriovenous fistula; CVC: central venous catheter; HD: haemodialysis; PD: peritoneal dialysis; SD: standard deviation.

Fig. 2 shows the flow of patients and the reasons why patients had CVC at the time of the study.

Reasons for patients having central venous catheters (CVC).

VA: vascular access; AVF: arteriovenous fistula.

- a)

Pending surgery for other reasons, including inability to perform VA surgery due to hospitalisation, other surgeries, etc.

- b)

Non-functioning VA, including: primary failure (9 patients - 3.5%) or recent thrombosis (2 patients - 0.78%).

- c)

Non-puncturable AVF including: maturing (8 patients - 3.13%); non-puncturable brachiobasilic AVF pending superficialisation (5 patients - 1.96%); fracture of the AVF arm preventing its use (2 patients - 0.78%).

- d)

Ruled out for vascular surgery, including: lack of vascular bed (25 patients - 9.8%), AVF closure due to ischaemia (4 patients - 1.56%), multiple previous thromboses (14 patients - 5.49%).

- e)

Ruled out by nephrology, including: age and/or comorbidity (36 patients - 14.1%), rest from peritoneal dialysis (3 patients - 1.17%), possible recovery of renal function (1 patient - 0.39%), on waiting list for living-donor transplant (2 patients - 0.78%).

- f)

Fear of AVF, including: fear of surgery and punctures due to previous bad experiences (31 patients - 12.1%) and fear of surgery and punctures without previous surgeries (27 patients - 10.5%).

- g)

Preference for catheter, including: aesthetics, comfort (34 patient - 13.3%).

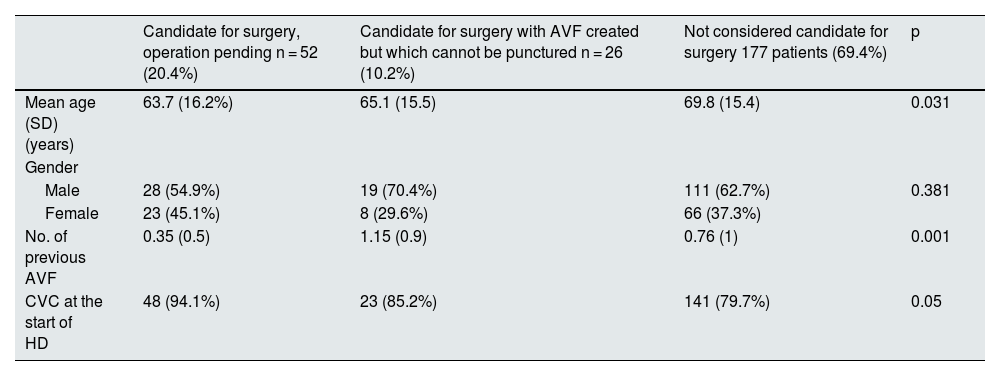

Table 3 shows the demographic characteristics of the different groups of prevalent patients with CVC.

Demographic characteristics of the different groups of prevalent patients with CVC.

| Candidate for surgery, operation pending n = 52 (20.4%) | Candidate for surgery with AVF created but which cannot be punctured n = 26 (10.2%) | Not considered candidate for surgery 177 patients (69.4%) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (SD) (years) | 63.7 (16.2%) | 65.1 (15.5) | 69.8 (15.4) | 0.031 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 28 (54.9%) | 19 (70.4%) | 111 (62.7%) | 0.381 |

| Female | 23 (45.1%) | 8 (29.6%) | 66 (37.3%) | |

| No. of previous AVF | 0.35 (0.5) | 1.15 (0.9) | 0.76 (1) | 0.001 |

| CVC at the start of HD | 48 (94.1%) | 23 (85.2%) | 141 (79.7%) | 0.05 |

AVF: arteriovenous fistula; CVC: central venous catheter; HD: haemodialysis; SD: standard deviation.

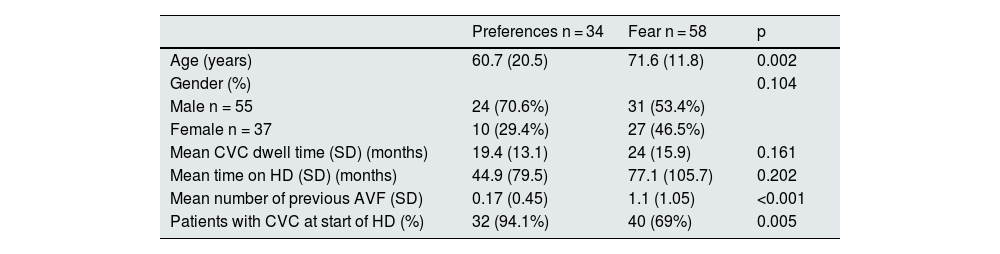

Out of the 255 HD patients with CVC, 92 (36%) refused to have an AVF. Two groups of patients were identified: those who were afraid of having an AVF either because of the punctures or the surgery, and those who preferred CVC to AVF for aesthetic reasons or comfort. The most common reason for having fear was having experience previous complications. Table 4 shows the differences between patients who refused due to fear and those who refused because of preference. Patients preferring CVC were younger and 94% had started HD with CVC.

Factors associated with causes of patient refusal of AVF creation (fear and preferences).

| Preferences n = 34 | Fear n = 58 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 60.7 (20.5) | 71.6 (11.8) | 0.002 |

| Gender (%) | 0.104 | ||

| Male n = 55 | 24 (70.6%) | 31 (53.4%) | |

| Female n = 37 | 10 (29.4%) | 27 (46.5%) | |

| Mean CVC dwell time (SD) (months) | 19.4 (13.1) | 24 (15.9) | 0.161 |

| Mean time on HD (SD) (months) | 44.9 (79.5) | 77.1 (105.7) | 0.202 |

| Mean number of previous AVF (SD) | 0.17 (0.45) | 1.1 (1.05) | <0.001 |

| Patients with CVC at start of HD (%) | 32 (94.1%) | 40 (69%) | 0.005 |

AVF: arteriovenous fistula; CVC: central venous catheter; HD: haemodialysis; SD: standard deviation.

The main finding of this study is that, despite the recommendations of clinical practice guidelines,6,7 the percentage of CVC in HD units remains high (in our study 20% above the recommendation by guideline [<25%]), which is in line with other similar publications.1–4

The variability between countries and centres,2–4 as was also evident in this study, raises the following dilemma: are there modifiable factors that can be controlled to achieve the objectives proposed by the guidelines? Or by contrast, nowadays, with the new criteria of personalisation and the active incorporation of the patient in decision-making on VA,15 should we assume that it is not possible to achieve the proposed objectives? Could we reverse the situation by acting differently or improving processes? Or should we change the guidelines and bring them into close to the reality?

Different factors may be contributing to the high prevalence of CVC in units: some are dependent on the patient,16 others on the surgical team,17 others on structural factors, and even factors that have arisen in recent years, such as the influence of the COVID pandemic on the creation of VA.18 A reflection about these factors may help to guide us towards measures that can be implemented to improve VA outcomes by focussing on factors that are modifiable.

In this study, unavoidable patient-dependent factors such as age, gender or non-Spanish nationality did not influence the overall higher use of CVC in prevalent patients and at the start of HD, although the group of patients who were rejected for surgery were older than the rest. Age alone is not considered a contraindication for AVF, but it is a complex and highly-debated issue that requires a balance between patient preference, the likelihood of the VA working, and potential complications in the context of limited patient survival.19,20 Although this may highlight the real difficulty of performing an AVF in an increasingly ageing population, with more comorbidity and poor vascular health, it is also susceptible to subjectivity, both by the nephrologist and the vascular surgeon. In fact, the experience and involvement of the vascular surgeon not only influences VA outcomes, but also the decision to rule a out a patient for creation of AVF or even the patient's refusal to undergo an AVF, and it could be is a modifiable factor.21,22 Studies have shown that increased training and continuing education in VA for residents, nephrologists and vascular surgeons can prevent patient refusal of AVF.23–25

Organisation is a factor that can be modified by many of us. Different models of VA management and the relationship between vascular surgery and nephrology have been shown to have an enormous influence on VA outcomes.26 In this study, up to 30% of patients, despite being considered candidates for AVF/prostheses, were dialysed via a CVC. Two thirds of them were patients who were still waiting for surgery and were at different stages of the process (Fig. 1), which illustrate the need for an improvement on VA planning. In addition to glomerular filtration rate and its progression,6,26 other factors have to be considered when deciding when to refer a patient for placement of VA; for example, waiting times in the vascular surgery department or the characteristics of the patient and their environment.27 The decision needs to be made on an individual basis and patients should be referred to surgery early if they are at risk of slower maturation or having complications (females, advanced age, diabetes mellitus, peripheral arterial disease, smoking or obesity),28,29 or if they may require more complex techniques (superficialisation)30; also in those cases with comorbidities with a risk of rapid decrease in glomerular filtration rate that may require an urgent initiation of HD31 or if their social or family situation makes them to be at risk of being lost to the clinic follow-up.32

Another avoidable factor identified in the present study is the fact that the use of CVC at the start of HD is associated with the need of urgent start of HD with no previous follow-up in the advanced chronic kidney disease (ACKD) clinic.33 The early detection of CKD and the dissemination of knowledge in primary care and other specialities so that these patients are referred early to nephrology continues to be a major challenge.34

Of note is the high percentage of patients found in this study who refused to have an AVF created (36%), due to fearor preference as the most important reasons. This fear is associated with the high prevalence of anxiety and depression that affect dialysis patients and will influence their preferences.35 In a nationwide study that analysed the most common causes of concern about surgery, the most important causes were: fear of the unknown, possible complications, impact on quality of life and pain control.36 The scientific community considers AVF to be the optimal VA based on the lower rate of infection, morbidity and mortality rates and lower costs. However, patients give priority to how the VA may affect their quality of life and future prospects.37,38 The association between fear and number of previous AVF attempts suggests the need to reduce negative experiences for patients. Choosing the best VA and the expert hands of both surgeons and nurses are important. In those that refuse to accept an AVF, a significant association has been reported,and also found in the present study, between the preference for a CVC and the fact of either having a CVC or having had one at some point39,40 so another modifiable aspect to minimise refusals is to prevent patients from starting haemodialysis with a CVC. The choice of VA together with the choice of renal replacement therapy is a process that requires both information and time in ACKD clinics.41 We need to be able to identify the barriers that prevent this information from being provided in an appropriate and individualized manner to each patient, based on specific communication techniques.42

Lastly, adequate VA surveillance using first- and second-generation methods allows for early detection of stenosis and prevention of thrombosis, and is a modifiable factor that can influence the rate of CVC. In this study, the thrombosis rates of both AVF and prosthesis were low and below the values recommended by the guidelines of the Grupo Español Multidisciplinar del Acceso Vascular (GEMAV) [Spanish Multidisciplinary Group on Vascular Access].6

The limitations of this study include its retrospective nature and, since it deals with data collected on arrival at the peripheral centre, it is difficult to gather specific data relating to the procedure within the ACKD or transplant clinic (for example, glomerular filtration rate [GFR] at the time of referral, the person providing information to the patient and with whom the decision about VA is made). However, this study has the following strengths: it shows results from a large sample of patients, coming from different centres, hospitals and autonomous regions, which offers a much broader view than if they were a single centre and fosters reflection on future initiatives to improve VA.

In conclusion, there are still modifiable causes that influence the high percentage of patients with CVC, necessitating a systematic evaluation to identify barriers to the process of AVF creation. Strategies are needed to promote the planning, creation and maintenance of VA from the ACKD clinic, with the main objective that most patients can have HD with the best possible VA after a personalised assessment by the multidisciplinary team, to ensure that outcomes are not the result of variability of criteria or poor organisation, management or experience of the healthcare professionals responsible for the VA.

FundingNo funding was received for this paper.