We thank Dr. Bocanegra et al. for their interest in our study.1

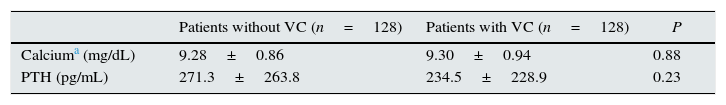

In their comments, they pointed out that the methods section did not provide the values of phosphorus, calcium, and PTH of the patients with and without valvular calcification (VC). Values of these parameters were not shown because we decided to include in the table only those values with differences that were statistically significant. Therefore, the values of phosphorus, being significantly different, were shown in Table 1 of the original article. In our study, the values of calcium and PTH were similar in both patient groups, with and without VC, and were within the range recommended by the KDOQI, as shown in Table 1 of this letter.

Levels of calcium and PTH in patients with and without valvular calcification.

| Patients without VC (n=128) | Patients with VC (n=128) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Calciuma (mg/dL) | 9.28±0.86 | 9.30±0.94 | 0.88 |

| PTH (pg/mL) | 271.3±263.8 | 234.5±228.9 | 0.23 |

VC, vascular calcification; PTH, parathyroid hormone.

Regarding the comment on the multivariate analysis of factors associated with VC, we would like to offer the following clarification: the analysis performed included those variables that showed a statistically significant difference between groups, including phosphorus. The analysis also included other variables that could have been associated with the calcification process: lipids, C-reactive protein, PTH, and calcium, though these variables were inadvertently omitted from text. We therefore thank Bocanegra et al. for the opportunity to provide this information. The results of the multivariate analysis showed that older age and lower albumin level were independently associated with VC, as shown in Table 3 of the article.

As Bocanegra et al. pointed out, our study demonstrates that the presence of VC is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular events and cardiovascular death, although it does not establish the factors involved in the development of VC, other than older age and lower albumin level. Similarly to other studies,2 our study found no association between VC and the biochemical abnormalities of bone mineral metabolism that are measured in routine clinical practice. Likewise, there was no association with atherogenic comorbidities nor with established atherosclerosis. This association has not been evaluated in most of the studies on VC in incident dialysis patients. In prevalent dialysis patients, VC has been associated with a history of cardiovascular events and left ventricular hypertrophy.3

The precise cellular and molecular mechanisms that drive cardiac and vascular ectopic calcification are not fully established. Vascular smooth muscle cells and endothelial and interstitial valvular cells differentiate into osteoblasts with the final result of calcification. The factors that initiate and promote mineralisation are both local, related to cellular stress (oxidative stress, autophagy, apoptosis, etc.) and systemic (multiple circulating factors).4,5 The overlap between inflammation and calcification is becoming more and more evident. It has been demonstrated in vivo that in atherosclerosis, infiltration by macrophages precedes osteogenic activity, indicating that macrophages promote a pro-inflammatory environment and send specific signals to vascular-wall cells to initiate osteogenic differentiation.5

We can conclude that in chronic kidney disease, there are numerous procalcifying factors. Chronic kidney disease leads to a state of low-grade inflammation, cellular stress, and systemic hormonal and bone-mineral metabolism abnormalities, creating an environment conducive to ectopic calcification. Given the complexity of the process, calcification may require the simultaneous action of several of these factors. Future research will provide more information to add to current knowledge.

Please cite this article as: Perales CS, de Castroviejo EVR. Calcificaciones valvulares en enfermedad renal crónica:¿enfermedad mineral ósea o riesgo cardiovascular previo? Respuesta. Nefrología. 2015;35:600–601.