Access to information on organ donation and transplantation among adolescents should be established as a strategic line of action. Health promotion campaigns have become a regular resource for governments.1 However, the actual value of these campaigns is debateable.2 In the case of organ donation, the impact of such campaigns is difficult to quantify and even more difficult is to create a campaign with the capacity to produce measurable changes on the ethics of adolescents that remains on their life.3

In general, most authors report that their donation promotion campaigns have a positive effect, but their evaluation systems are often controversial.

The aim of this study is to determine the utility of an information campaign on donation and transplantation in changing adolescents’ attitudes towards organ donation.

We designed a longitudinal study with repeated measurements of attitudes towards organ donation in the adolescent population using a pre-validated questionnaire, one month and six months after the information campaign.

The information campaign was designed by the Autonomous Transplant Coordination, the Clinical Transplant Unit and the University. It consists of four parts: interactive talk with healthcare professionals from the transplant team; transplant patients sharing their experiences; teaching material designed for this campaign handed out and discussed with the teenagers; answering of questions and comments.

The study population consisted of adolescents aged 14–16 selected from six Secondary Schools. The estimated sample size was 1080. We used the validated PCID-DTO-Rios questionnaire.4,5

The independent variable of the study was the attitude towards organ donation at death, with three response options: in favour of donating, against donating or undecided. We compared the results at one and six months.

The study group consisted of 992 adolescents (mean age: 15±0.9 years) and 49.1% said they would donate organs, 37.1% were undecided and 13.8% said they would not donate organs.

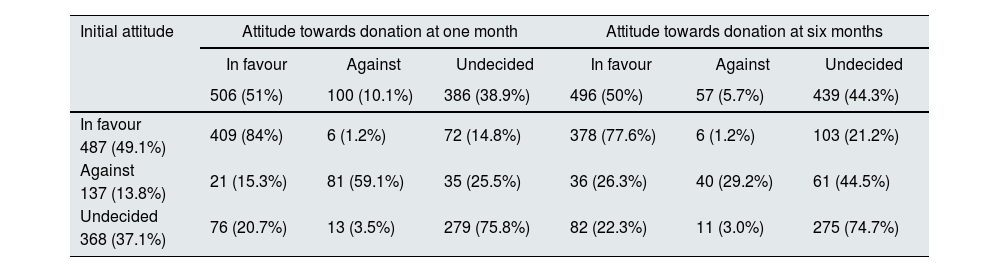

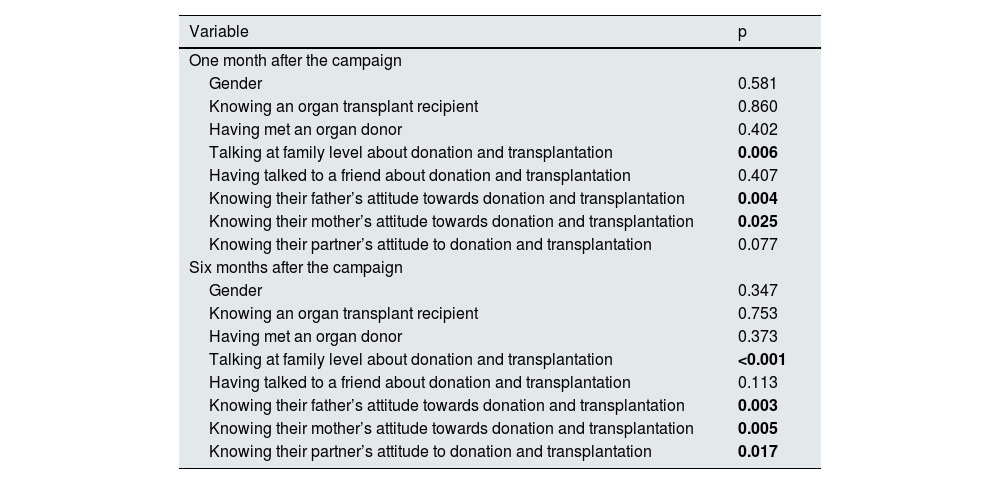

The one-month assessment of the utility of the campaign found that 51% were in favour, 38.9% undecided and 10.1% against, with 22.5% having changed their attitude towards donation. Analysing factors that might influence the campaign’s effect on the adolescents’ attitudes, the following were predominant: having talked at family level about donation and transplantation; and learning the opinion of their parents towards organ donation.

In the six-month assessment, 50% of the adolescents were in favour of donation, with 5.7% against and 44.3% undecided. The influencing factors were the same as in the one-month assessment.

Overall assessment of the utility of the campaign as a tool to promote organ donation: the pro-donation attitude of adolescents increased from 49% at the beginning to 51% in the first month and 50% after six months (Table 1). The attitude against donation progressively decreased from 13.8% at the beginning to 10.1% in the first month and 5.7% after six months. Lastly, the number of adolescents undecided about organ donation showed a progressive increase, from the initial 37.1%–38.9% at one month and 44.3% at six months. Table 2 shows the main social-personal factors that may be associated with attitudes towards organ donation at one month and six months after the campaign.

Change in attitude towards organ donation in adolescents one month and six months after participating in the organ donation information campaign.

| Initial attitude | Attitude towards donation at one month | Attitude towards donation at six months | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In favour | Against | Undecided | In favour | Against | Undecided | |

| 506 (51%) | 100 (10.1%) | 386 (38.9%) | 496 (50%) | 57 (5.7%) | 439 (44.3%) | |

| In favour | 409 (84%) | 6 (1.2%) | 72 (14.8%) | 378 (77.6%) | 6 (1.2%) | 103 (21.2%) |

| 487 (49.1%) | ||||||

| Against | 21 (15.3%) | 81 (59.1%) | 35 (25.5%) | 36 (26.3%) | 40 (29.2%) | 61 (44.5%) |

| 137 (13.8%) | ||||||

| Undecided | 76 (20.7%) | 13 (3.5%) | 279 (75.8%) | 82 (22.3%) | 11 (3.0%) | 275 (74.7%) |

| 368 (37.1%) | ||||||

n=992; p<0.001.

Analysis of social-personal factors that may be associated with attitudes towards organ donation one month and six months after the campaign.

| Variable | p |

|---|---|

| One month after the campaign | |

| Gender | 0.581 |

| Knowing an organ transplant recipient | 0.860 |

| Having met an organ donor | 0.402 |

| Talking at family level about donation and transplantation | 0.006 |

| Having talked to a friend about donation and transplantation | 0.407 |

| Knowing their father’s attitude towards donation and transplantation | 0.004 |

| Knowing their mother’s attitude towards donation and transplantation | 0.025 |

| Knowing their partner’s attitude to donation and transplantation | 0.077 |

| Six months after the campaign | |

| Gender | 0.347 |

| Knowing an organ transplant recipient | 0.753 |

| Having met an organ donor | 0.373 |

| Talking at family level about donation and transplantation | <0.001 |

| Having talked to a friend about donation and transplantation | 0.113 |

| Knowing their father’s attitude towards donation and transplantation | 0.003 |

| Knowing their mother’s attitude towards donation and transplantation | 0.005 |

| Knowing their partner’s attitude to donation and transplantation | 0.017 |

Bold: significant results (p<0.05).

Health promotion and education campaigns have become common practice because of their supposedly positive effect. However, the utility and benefits are questioned in view of the large number of resources they require. There are many campaigns promoting donation and transplantation, but few results have been analysed in depth. In our study, the results show that the implementation of a specific campaign to promote donation among adolescents led to a change of attitude. However, the change is not as favourable as one might expect. Other studies measuring the effect of an adolescent outreach campaign reported better results, but they tended to conduct the evaluation very early, sometimes a week after the campaign.6

Back in 2009, in a meta-analysis quantitatively synthesising previous studies evaluating organ donation communication campaigns, Feeley and Moon7 discovered that many of these campaigns also had small effects. The “value” of our study is that it focuses on adolescents, whereas most previous studies have focused on adults. Another important value is our data on talking with their families, particularly as having such talks not only predicts movement from being against to unsure or in favour, but also from being in favour to unsure or against, which may happen if family conversations end up reinforcing stereotypes and media misinformation. Our study tries to clarify why such campaigns may have limited impact, among other reasons the campaign did not succeed in motivating most adolescents to talk to their families. In this respect, we agree with many previous studies showing that these campaigns often have limited effects.7

In conclusion, specific campaigns to promote organ donation among adolescents have a positive impact of uncertain utility.

Authorship- 1)

Conception and design: A. Ríos, M. Rigabert.

- 2)

Collection of a substantial part of the data: A. Ríos, M. Rigabert, A. López-Navas, A. Balaguer-Román.

- 3)

Data analysis and interpretation: A. Ríos, M. Rigabert, A. López-Navas, A. Balaguer-Román.

- 4)

Drafting of the manuscript: A. Ríos.

- 5)

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: A. Ríos, M. Rigabert, A. López-Navas, A. Balaguer-Román.

- 6)

Statistical expertise: A. Ríos.

- 7)

Obtaining funding for this project or study: A. Ríos.

- 8)

Supervision: A. Ríos.

- 9)

Final approval of the version to be published: A. Ríos, M. Rigabert, A. López-Navas, A. Balaguer-Román.