Basic renal function tests such as maximum urine osmolality and urinary elimination of albumin and N-acetyl-glucosaminidase often reveal abnormalities in clinical cases involving hyperpressure in the urinary tract or loss of renal parenchyma. However, in all the available algorithms dedicated to the study of children with urinary tract infection or dilation, the benefit of using these functional parameters is not mentioned. In this review, we provide information about the practical usefulness of assessing the basic renal function parameters. From these data, we propose an algorithm that combines morphological and functional parameters to make a reasoned case for voiding cystourethrography.

Las pruebas básicas de estudio de la función renal como la osmolalidad urinaria máxima y la eliminación urinaria de albúmina y de N-acetil-glucosaminidasa se alteran con mucha frecuencia en situaciones clínicas que cursan con hiperpresión en la vía urinaria o con pérdida de parénquima renal. No obstante, en todos los algoritmos que se pueden consultar dedicados al estudio de los niños con infección urinaria o dilatación de la vía urinaria nunca se menciona el beneficio del uso de esos parámetros funcionales. En esta revisión, ofrecemos información acerca de la utilidad práctica que conlleva la determinación de los parámetros básicos de estudio de la función renal. A partir de esos datos proponemos un algoritmo destinado a realizar una petición razonada de la cistografía conjuntando parámetros morfológicos y funcionales.

“The truth that seems hardest is but a kernel of another, more complete, truth, but it is never fully complete; and only thus can it be interpreted and judged.”

In paediatric practice there are two very common situations in which it becomes necessary to make decisions regarding the morphological tests that we should use in young patients. We refer to urinary tract infections (UTI) and congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract (CAKUT) that are all too often detected on ultrasounds performed in utero. In many cases, both situations occur simultaneously.

In the context of UTIs, specifically, the indication criteria for the tests to be performed have varied widely over time. Since vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) is a common finding in patients with UTI, the idea that it played a role in its pathogenesis was soon established, and so cystography was indicated and is still performed in many communities when facing a first infection. In addition, the idea that VUR was the cause of renal scarring resulting in the intiation chronic kidney failure, was cemented. It is from this that the term “reflux nephropathy” was coined, which has now fortunately been replaced by “nefropatía cicatricial [scarring nephropathy]” in Spanish. This “fear” of not diagnosing VUR early enough to prevent its potential complications ended up developing into a view that has been called the “reflux-centric” paradigm.1 Luckily this notion has been changing in recent years towards more cautious approaches.2,3

In all the algorithms dedicated to evaluation of children with UTI or CAKUT that can be consulted, kidney function parameters never appear among the variables or conditions that lead to ordering imaging test .4–6 This even happens in the algorithms designed by nephrologists. In this review, we offer information about the utility of basic kidney function tests in the management of children with UTI and CAKUT. Specifically, we will refer to testing the kidneys’ ability to manage water (maximum urine osmolality) and urinary elimination of albumin and N-acetyl-glucosaminidase (NAG).

Overview: on renal concentrating capacity, albuminuria, and N-acetyl-glucosaminidaseThe history of testing the kidneys’ ability to finely adjust the body's water metabolism using urine concentration and dilution mechanisms goes back more than one and a half centuries. In 1859, Hoppe-Seyler (1825–1895) (Fig. 1), a German physiologist and chemist, demonstrated that when urine and serum from the same animal were separated by a membrane from a pig bladder, the flow direction was from the plasma towards the urine.7 As a result, he had discovered that urine could be more concentrated that the glomerular ultrafiltrate. Years later in Tübingen in 1892, Dreser (1860–1925) studied the physiology of water excretion. He established that the freezing point depression of blood determined cryoscopy (−0.56°C) was not altered by water intake, in contrast to what happens with urine. During water restriction, Dreser demonstrated that the freezing point of urine decreased −2.40°C in humans, in other words, the osmotic pressure of urine may be higher than that of plasma.8 In a patient with diabetes insipidus, the freezing point of urine was only −0.20°C; as described by Richet, probably the first ever use of cryoscopy in a patient.9 Shortly afterwards in Paris, Winter determined the freezing point of many fluids and confirmed Dreser's findings.10

Later, the Hungarian doctor Korányi (1866–1944) supposed that the kidneys regulate the osmotic pressure of urine so that the osmotic pressure of blood remains constant. To do this, he studied the changes in the freezing point depression of urine during water restriction and observed that in patients with terminal uraemia the osmotic pressure of urine hardly changed and was significantly closer to the value for plasma.9,11 He called this situation isostenuria. Based on these findings, he was the first to introduce the functional concept of renal insufficiency.12 It should therefore be noted that this very familiar term for current nephrologists arose from the study of the kidneys’ ability to manage water.

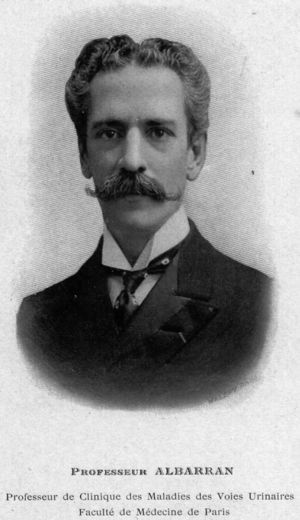

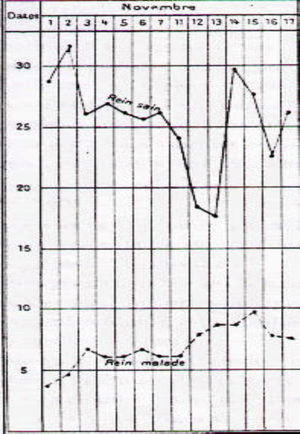

Albarrán (1860–1912) (Fig. 2) was a Cuban urologist who studied medicine in Barcelona. In 1878 he moved to Paris where he worked with the anatomist Ranvier (1835–1922) and the urologist Guyon (1831–1920). Albarrán was responsible for a basic and little known discovery. At a time when the only known imaging test was the recently discovered X-ray, he could discern which kidney was diseased in the case of unilateral lesions potentially requiring surgery, such as, for example, in renal tuberculosis. To do this, he created the so-called “Albarran lever”, a small addition to the cystoscope through which he could direct a catheter towards to the ureteral meatus to directly collect urine coming from each kidney.13 Afterwards, he created one of the first stimulus function tests, the “experimental polyuria” test. In the presence of a water stimulus, the healthy kidney adapted to the stimulus and the disease one did not14 (Fig. 3). His book, Exploration des functions rénales, written in 1905 is, surely, the first in history on the topic and a historical debt held collectively by nephrologists.14

Joaquín Albarrán's “experimental polyuria” test. In the presence of a water stimulus, the healthy kidney (rein sain) adapts by increasing the volume of urine and the diseased kidney (rein malade) does not.14.

In 1909, Ambard and Papin laid out the concept of maximum concentration, thus providing all the elements for a new function assessment index. At that time it was known that, even during periods of severe dehydration, urine continued to be formed. It is what came to be called the “obligatory urine” of Ambard and Papin.15

Soon tests were designed to stimulate the maximum urine concentrating capacity by restricting liquids, such as the tests by Volhard16 and Addis and Schevky,17 in which the osmotic pressure of urine was no longer determined but rather its density (specific gravity). In any case, with these tests the production of endogenous ADH was stimulated. Decades later, the so-called “dry diet” test would also become standard in children starting at 2 years of age, although it measured urinary osmolality.18

Starting in the 1910s, information about how the pituitary gland regulates water excretion through the kidneys began to be available.19 Soon it could be demonstrated that the posterior portion of this gland produced an antidiuretic substance that behaves like an “authentic” hormone by passing through circulation and acting on the kidney.20 Subsequently, pituitary extracts started to be used to determine maximum urinary osmolality.21,22

In 1968, a synthetic analogue of vasopressin, desmopressin, became available23 and concentration test could be conducted more comfortably and in less time since it had a greater antidiuretic effect than the natural hormone.24

It is outside the scope of this review to discuss the anatomic and functional complexity of the kidney's urine concentrating mechanism, the details of which have been coming to light, as indicated above, for more than a century and a half with key moments such as understanding the countercurrent mechanism25 or the discovery of aquaporins.26

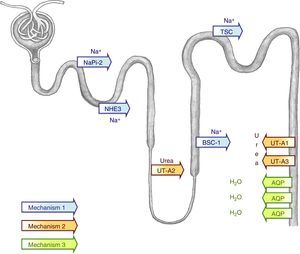

Remember that the renal concentrating capacity depends on an adequate glomerular ultrafiltrate supply to the tubules, a hypertonic medullary interstitium, a structurally intact medullary countercurrent mechanism,25 and normal water permeability of the tubules in response to vasopressin. The concentrating capacity is dependent on the renal medulla.27 The degree of medullary concentration is established primordially by the renal tubules in the loop of Henle and the blood vessels surrounding it (vasa recta) during the countercurrent exchange process. The purpose of this mechanism is to create a hypertonic medullar interstitium.25 In this hypertonic interstitium, vasopressin can concentrate the urine through a passive water equilibrium mechanism in the main cells of the collecting ducts, which allows the tubular lumen contents to equilibrate with the hypertonic medullary interstitium.28 Vasopressin secretion in response to water restriction causes the intracellular aquaporin-2 vesicles (AQP2) to relocate in the apical membrane of the main collecting duct cells. This shift allows water to be reabsorbed from the tubular lumen into the cell and, therefore, concentration of the final urine29 (Fig. 4).

Simplified model of the urine concentrating mechanism. To create a hypertonic medullary interstitium, adequate function of all the tubular sodium transporters is necessary, for example, NHE3 (type 3 Na+/H+ exchanger), NaPi-2, (type 2 Na-Pi cotransporter), BSC-1 (type 1 bumetanide-sensitive Na-K-2Cl cotransporter), or TSC (thiazide-sensitive cotransporter) in the lumen side of the tubule (mechanism 1). A defect in its function would cause a loss of saline with an accompanied loss of water that would cause a less hypertonic medullary interstitium. Furthermore, adequate function of the urea transporters (UT-A1, UT-A2, UT-A3) is necessary to increase the medullary interstitium osmolality (mechanism 2). In the presence of this hypertonic medullary interstitium, vasopressin can concentrate the urine thanks to the stimulus it exercises on the aquaporins (AQP), which enables the tubular lumen content to become equilibrated with the hypertonic medullar interstitium (mechanism 3).

The introduction of albuminuria and NAG determination in clinical practice is much more recent. Nevertheless, finding proteinuria was one of the first kidney function tests discovered in history., In 1764 Cotugno (1736–1822) described a typical case of acute nephritis with anasarca and large quantities of a heat-coagulable substance ovi albumini persimilem in the urine.30 His findings were confirmed years later by the English physician Blackall (1771–1860). Nevertheless, at the end of the 1980s, suitable techniques were available that enabled small quantities of albumin to be measured that were not measurable with earlier techniques. The term microalbuminuria has been widely used to refer to it, despite being incorrect from a semantic point of view. Therefore it is better to simply use the name albuminuria. It was initially used in clinical practice to try to detect incipient diabetic nephropathy.31 Since then it has been demonstrated that continued elevated excretion is an early sign of glomerular damage in processes that occur with hyperfiltration, both in cases in which the patients had all their nephrons (diabetic nephropathy32, obesity33) as well as in those where there is loss of parenchyma.34 Later it was demonstrated that it is also a good predictor of developing cardiovascular disease.35 In children, it has been observed that it can be elevated in cases of VUR.36,37 One unknown question is if this increase is due to the parenchymal loss that may exist in some VUR cases (renal dysplasia, scarring) or to the elevated pressure of VUR on the urinary tract.

Since the 1960s it has been known that NAG is an enzyme present in kidney tissues,38 in the lysosomes of the proximal tubular cells, and that its excretion in urine increases when cells are damaged and NAG is releases into the tubular lumen .39 Classically, the determination of NAG was used to evaluate the nephrotoxicity caused by aminoglycoside antibiotics.40 Moreover, NAG levels may be increased in cases of elevated intratubular pressure as in urinary tract obstruction41 and in VUR, although in this case, as occurs with albuminuria, it is difficult to know if it is due to the elevated pressure or to the associated reduction of glomerular filtration.36

On basic determinations of kidney function as markers of parenchyma lossIn a study including 77 children with normal renal parenchyma as confirmed by dimercaptosuccinic acid scan and 102 children with loss of parenchyma (one or more scars, single kidney, hypodysplasia), we determined the quality and diagnostic efficiency of the kidney function markers listed above. The sensitivity of maximum urine osmolality was 30.4% for detecting loss of parenchyma (84.8% specificity), 15.6% for urinary albumin excretion (92.1% specificity), 11.5% for NAG/creatinine ratio (100% specificity), and 8.9% for glomerular filtration rate (GFR) (100% specificity). However, it is striking that higher sensitivity (37.9%) was observed with urine volume corrected for 100ml of GFR. This finding demonstrates how this parameter that is rarely used, but is easy to calculate, (plasma creatinine×100/urine creatine) can be very useful in daily practice. In any case, it was demonstrated that the parameters that reflects the kidneys’ ability to manage water are the most sensitive for detecting loss of parenchyma.42 As a corollary to this study, we can emphasize that GFR was the least sensitive parameter and that the sensitivity reached with the parameters studying the kidneys’ ability to manage water was very low; therefore, currently we do not have methods that can adequately assess a modest nephron loss.

In 2008, in a study including data from 160 children with UTI or CAKUT, we proved that, in those with a normal maximum urine osmolality, the GFR was always normal while all patients with a reduced GFR had an altered concentrating capacity.43 In that study, the GFR was calculated with the classic Schwartz formula that uses a constant value of 0.55, which now we recognize that it overestimates GFR. In a recent review using the new formulas to calculate the GFR including cystatin C that are more accurate,44 we observed that a few children in stage G2 chronic kidney disease still concentrate well (near the lower limit of normality), but they are the exception that confirm the rule (data not published). In daily practice with our young patients if the maximum urine osmolality is normal we do not draw blood to confirm a normal GFR.

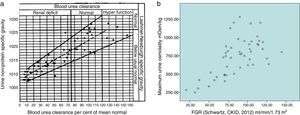

As is known, in the Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease 2012 (KDIGO Guidelines), stage G1 of chronic kidney disease is defined by the presence of abnormalities of kidney structure or function, present for at least 3 months and not accompanied by GFR deterioration.45 Interestedly, the authors of the guidelines, among other functional alterations, included increased albuminuria but did not mention changes in the kidney's ability to manage water. In a recent study, we studied 116 children with an abnormal dimercaptosuccinic acid scan.46 Among the 100 children in stage G1 included, the frequency of a concentrating capacity defect (29%) and increased urine volume (20%) was higher than that of an increase in albuminuria (12%) and urinary excretion of NAG (3%). All the included children in stages G2-G5 had alterations in the kidneys’ ability to manage water. Furthermore, a direct correlation was observed between the GFR calculated with the 2012 CKID Schwartz formula47 and the maximum urine osmolality (r=0.63; p<0.001) (Fig. 5b).

(a) In 1934 Alving and Van Slyke observed a direct correlation between urea clearance and the maximum urine specific gravity (density) obtained with a “dry diet”. (b) In a group of current paediatric patients we found a correlation with a similar slope between the GFR and the maximum urine osmolality reached after desmopressin stimulation. Observe that in both figures the points are more dispersed in cases with normal GFR than when the kidney disease is advanced.

All the data listed in this section coincide with what Korányi began to glimpse a century ago9,11,12 and with what was confirmed by both Alving and van Slyke in 193448 (Fig. 5a) and Epstein in 1966.49 In the words of this last author: “The ability of the kidneys to excrete a concentrated urine is impaired together with other renal functions whenever the kidneys are progressively scarred and the amount of functioning renal parenchyma is diminished. Concentrating capacity and glomerular filtration rate are therefore reduced roughly in parallel in many common diseases which cause widespread scarring of the kidneys”.49

On basic determinations of kidney function as markers of elevated pressure on the renal parenchymaThe results obtained in the experimental models that cause elevated pressure in the urinary tract are difficult to extrapolate to malformations that occur with hydronephrosis in humans, for two reasons. The first is that in both VUR and uteropelvic junction (UPJ) obstruction there may be an associated glomerular loss (renal dysplasia, scarring). The second is that in mild or moderate VUR the elevated pressure can be intermittent and in UPJ obstruction the pressure may vary extensively according to the degree of obstruction in the uteropelvic junction.

The authors’ concern about the presence of functional lesion in cases of hydronephrosis come from the past.50 In the 1960s it was demonstrated that an experimental ureteral obstruction produced an impairment in concentrating capacity.51 The possibility of using desmopressin allowed the determination maximum urine osmolality that was reduced in both adults52,53 and children with hydronephrosis and particularly in cases of UPJ obstruction.54,55 In addition, an association between VUR and a defect in concentrating capacity been frequentlydescribed.56–61

In recent years, there has been studies to identify the mechanisms that enable the kidney to handle water in situations of elevated pressure. Thus, it has been observed that urinary obstruction causes a reduction in: the activity of some sodium transporters in the tubules62–64 (mechanism 1, Fig. 4), the expression of the urea transporters65 (mechanism 2, Fig. 4), and in the activity of the aquaporins expressed in the collecting duct64,66 (mechanism 3, Fig. 4). All these changes cause polyuria and renal salt losses.

An increase in urine excretion of albumin has been described in both UPJ obstruction67 and VUR.36,37,68 Elevated excretion of NAG and other proteins, are markers of proximal tubule injury, have been shown in both circumstances, UPJ obstruction41,69,70 and VUR.36,71–73

In paediatric medicine there are cases of urinary tract dilation that are not secondary to VUR or to obstruction and there is evidenced elevated pressure in the urinary tract. For the cases in which the diameter of the renal pelvis is greater than 2cm and there is no elevated pressure, the term “primary hydronephrosis” has been used, and if the ureter is also dilated the expression “non-obstructive megaureter” has been used. So, in a study including 38 children with a pelvic diameter greater than 2cm, we studied if there were differences in the kidney function in the different types morphological abnormalities.74 Maximum urine osmolality was reduced in 100% of the VUR cases, in 75% of the UPJ obstruction cases, and in only 16.7% of the primary hydronephrosis cases. Albumin excretion in urine was increased in 62.5% of VUR cases and in only 8.3% of UPJ obstruction cases, and in 11.1% of primary hydronephrosis cases. In turn, NAG excretion was elevated in 42.8% of VUR cases, in 25% of UPJ obstruction cases, and in 6.7% of cases of primary hydronephrosis. Thus they observed how it is the most sensitive concentrating test for detecting alterations in kidney function in cases of hydronephrosis. Furthermore, albuminuria was especially elevated in the VUR cases, NAG is a less sensitive marker of elevated pressure than maximum urine osmolality, and, in cases of the primary hydronephrosis, kidney function was rarely altered.74

Dilatation of pyelocalix is a morphological abnormality (renal pelvis between 0.5 and 2cm in diameter), that is being increasingly diagnosed since the universal introduction of ultrasound scans performed in utero for pregnant women. Ectasias may be a sign of VUR or underlying obstructions but, in most cases the cause is not identifiable, in such a case it is named simple pyelectasis. Nevertheless, since it may be expression of underlying pathology, the question is whether all children should be studied using imaging tests that are expensive, not free of risk, and exposition to radiation. In a prospective study in which we evaluated 79 children with pyelectasis, 11 patients had VUR of different degrees.75 As compared with VUR patients, the 68 children without VUR showed a significantly higher maximum urine osmolality, while the albumin/creatine and NAG/creatinine ratios were significantly lower. The negative predictive value of the first two tests was 93%, which indicates that cystography may not be necessary, in those cases with normal maximum urine osmolality and albuminuria.75

In a longitudinal study including children with differing grades of VUR we observed that, at the time of diagnosis, the maximum urine osmolality was reduced in 69.5% of them61 but at the end of the follow-up period it was only present in 19.5%.76 At the beginning, the concentrating capacity defect was related to the degree of VUR and at the end of the follow up, the defect in concentration was related to the loss of parenchyma rather than the initial degree of VUR. As for albuminuria, there were no differences between the beginning and the end of the follow-up (19.6% vs. 17.6%). No correlation was observed between the degree of albuminuria and the intensity of VUR. It was concluded that urinary excretion of albumin is a preferred marker of hyperfiltration and loss of renal mass in children with VUR correlated.77 As for NAG, at the time of diagnosis it was elevated in 37% of cases; conversely, at the end of follow up it was normal in all cases. This suggests in these cases, urinary excretion of NAG is a moderately sensitive marker of elevated pressure in the urinary tract.78

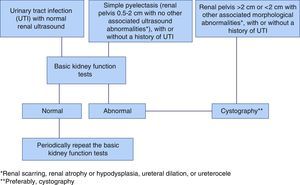

On the specific case of vesicoureteral reflux in children who have urinary tract infections. An algorithm based on the basic tests of kidney function. EpilogueThe indication of voiding cystourethrography in series (VCUG) has varied over the years. For a long time it was thought that it should be ordered in all cases of UTI, especially in young children, and especially in males.79 This was motivated by the untrue belief that the cure of VUR, no matter its grade, would prevent the onset of new cases of UTI and secondary kidney damage. However this strategy has been a matter of debate because of the following reasons1–3,5,83: many cases of VUR heal spontaneously with time,80,81 low degree of VUR do not alter kidney function,76 and VUR is not the final cause of the UTIs82. One of the key questions on this topic is: Would there be any problems if low-intensity VUR is not diagnosed? We believe that the answer is “no”, because what is truly important is the quality and quantity of existing renal parenchyma and ensuring that kidney function is undamaged, using the most sensitive methods mentioned in this review. As indicated above, many cases of mild urinary tract dilation are not associated with VUR and, if they are, it is usually mild. The end result is that in both circumstances (UTI and ectasias), many VCUGs are normal and, therefore, unnecessary. We wanted to prove whether the combination of ultrasound tests and sensitive function tests could acceptably predict that the VCUG will be negative and, therefore, prevent it from being ordered.84 We thus collected ultrasound results and functional tests from 100 children with a normal VCUG and from 63 diagnosed with VUR (10 mild grade [I–II], 26 moderate [III], and 27 severe [IV–V]). The most sensitive morphological abnormalities for suspecting VUR were renal scarring, atrophic or hypodysplastic kidneys, hydronephrosis, and pyelolalix ectasia associated with other morphological abnormalities. In terms of kidney function, statistically significant differences (p=0.004) were shown by comparing maximum urine osmolality in children with or without VUR. The urinary excretion values of albumin and NAG were not sensitive, but very specific (87.9%) in the VUR cases. Combining the morphological and function parameters, 70% of children with mild VUR, 76.9% of those with moderate VUR, and 100% with severe VUR had morphological or function abnormalities. Thus, the highest negative predictive value (80.8%) for detecting VUR was obtained by combining morphological abnormalities, excluding simple pyelectasis, those who only had kidney functional abnormalities, and those with both functional and morphological alterations (116/163). Moreover, in those cases, the sensitivity for diagnosing VUR was 85.7%. Our conclusion is simple: if kidney function is normal, especially the concentrating capacity, and if there are no morphological abnormalities other than pyelectasis, the use of VCUG is not initially indicated. (Fig. 6). It is necessary to emphasize that, in the case of recent pyelonephritis, the tests should be performed after 2 and 4 month in order to avoid artefact in the results.

In summary, the appropriate use of the basic kidney function tests offers the possibility of changing the strategy of ordering imaging tests in routine clinical practice in children with loss of renal parenchyma or urinary tract dilation. The renal concentration mechanism is so complex that any abnormality has repercussions on the maximum urine osmolality; as mentioned above, it is the first functional abnormality detected in many kidney disorders. Thus, in the absence of hydronephrosis, in children with UTI or ectasia of pyelocalix, ordering VCUG or nuclear medicine tests could be put off initially if the maximum urine osmolality and urinary excretion of albumin are normal. Conversely, abnormal kidney function would require further tests so the origin of these abnormalities is identified.

As written by Marañón in his Crítica de la Medicina dogmática (1950): “I want to tell to those working close to me, never forget that each thing that doctors know should be known as precisely as possible, but being aware that its value may be temporal.”

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: García-Nieto VM, Luis-Yanes MI, Arango-Sancho P, Sotoca-Fernandez JV. Utilidad de las pruebas básicas de estudio de la función renal en la toma de decisiones en niños con pérdida de parénquima renal o dilatación de la vía urinaria. Nefrologia. 2016;36:222–231.