Presentamos el caso de una paciente en Diálisis Peritoneal Automática (DPA) con peritonitis tuberculosa y posible vía de infección peritoneal por contigüidad desde trompa y ovario izquierdo, con cultivo de líquido peritoneal persistentemente negativo y mala evolución clínica. Como únicos antecedentes, destacaba cuadro de hipercalcemia seis meses antes de la peritonitis, náuseas y vómitos ocasionales. El diagnóstico de confirmación se realizó mediante biopsia peritoneal vía laparoscópica con retirada de catéter peritoneal y anexectomía izquierda. Actualmente, la paciente se encuentra asintomática realizando hemodiálisis diaria domiciliaria.

We report a patient in Automatic Peritoneal Dialysis (APD) with tuberculous peritonitis by possible peritoneal infection due to the proximity between fallopian tube and the left ovary, a peritoneal liquid culture was constantly negative. The patient presented a bad clinic evolution. Her only medical history was hypercalcemia six months before developing a peritonitis and occasionally nausea and vomits To confirm the diagnosis it was needed a peritoneal biopsy by means of a laparoscopy with a removal of the peritoneal catheter and left anexectomy. Now, the patient is asintomatic in daily home hemodialysis.

INTRODUCTION

The incidence of Tuberculosis (TB) in the Renal Replacement Therapy (RRT) population is six to sixteen times greater than in the general population, due to factors with alterations of cell immunity regulated by T lymphocytes, malnutrition and associated comorbidity among others.3However, few cases have been described on tuberculous peritonitis in peritoneal dialysis.

Different studies have reported the predominance of extrapulmonary TB in patients on RRT, mainly presenting in the first 36 months after starting dialysis and more common in patients on peritoneal dialysis as compared with those on haemodialysis.11

CASE REPORT

We report the clinical case of a 50 year-old woman on home automated peritoneal dialysis since 2002 for chronic renal insufficiency secondary to hypocomplementaemic glomerulonephritis. In her history the most remarkable pathologies were hypothyroidism on long term treatment, renal osteodystrophy treated with phosphorus binders, vitamin D and calcium supplements, and a single episode of peritonitis in June 2006 due to enterococcus faecalis with prompt recovery.

In August 2007, she presented with mild symptoms of hypercalcaemia (10.5mg/dl) consisting of nausea and vomiting without an associated weight loss, requiring a progressive decrease of calcium supplements and a calcium decrease in dialysis fluid.

Three months later (November 2007), she presented with peritonitis and negative culture for which empiric antibiotic treatment was initiated according to protocol. The peritoneal fluid remained turbid for one week. Following this, evolution was favourable, treatment being completed with cephotaxime and tobramycin for two more weeks.

The patient continued with peritoneal dialysis, with persistent occasional nausea and the only biochemical abnormality was corrected calcium of 10.3mg/dl.

In December 2007, she presented again with recurrent peritonitis which required hospital admission three days after starting intraperitoneal antibiotic treatment (vancomycin, tobramycin, and ampicillin) because of lack of response and persistent turbid fluid with negative cultures.

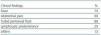

At admission, the patient had no fever. On physical examination, the only sign of abdominal pain with peritonism, mainly in the left iliac fossa. Biochemistry results showed elevated corrected calcium, severe hypoalbuminaemia, and an ADA of 49 (table 1).

The Mantoux test, haemocultures, culture of peritoneal fluid and AFB in peritoneal fluid were negative.

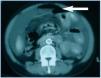

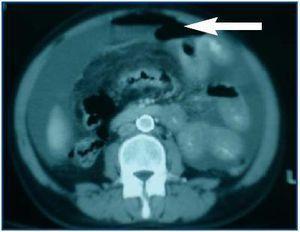

In spite of antibiotic treatment, the patient remained clinically symptomatic. In an abdominal Computerized Axial Tomography (CAT), hydropneumoperitoneum in small quantity was visible as were cysts in both ovaries, the left side larger in size (figure 1).

With suspicion of peritonitis secondary to gynaecological pathology, Gynaecological Department consultation was requested, and the adnexal images were interpreted as functional cysts without another associated pathology.

Given the poor clinical evolution with critical abdominal pain, the persistence of turbid fluid with a negative culture, and the high suspicion of secondary peritonitis, an urgent laparoscopy was done. In this, abundant fibrin, adhesion between intestinal loops and a mass adhered to the pelvis which was not able to be freed were analyzed. Abundant whitish nodes were visible throughout the peritoneum, and because of this, an exploratory laparotomy was done. The left fallopian tube was found very oedematous for which a gynaecological opinion was requested.

The gynaecological findings were: left twisted cystic ovary with an erythematous left fallopian tube. A left adnexectomy was performed.

The patient required a 48 hour admission into the intensive care unit because of haemodynamic instability. Broad-spectrum antibiotic treatment (imipenem and fluconazole) together with tuberculostatics (isoniazid, riphampicin, and pyrazinamide) was started due to high suspicion of tuberculous peritonitis.

The confirming diagnosis was obtained through the culture and biopsy of peritoneal nodes, left ovary and left fallopian tube, where there was evidence of epithelioid granulomas and positive AFB staining. Following this, the presence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis was confirmed in the tissue cultures.

The patient needed nutritional support (parenterally) and daily haemodialysis for a month. Fifteen days after withdrawal of the peritoneal catheter, the abdominal ultrasound showed free fluid with internal septa which normalized a month and a half after initiation of tuberculostatic treatment.

Presently, the patient has begun daily dialysis at home and has remained asymptomatic since hospital release.

DISCUSSION

There is a high prevalence of tuberculous infection in patients on peritoneal dialysis, especially those on continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis,1 particularly in those located in endemic areas such as Galicia,2 with extrapulmonary localization being the most frequent form of manifestation (more than 50% of cases).3

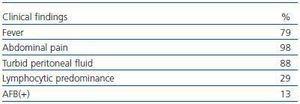

Clinical presence of tuberculous peritonitis is indistinguishable from bacterial peritonitis (table 2), except that it has a more insidious initiation and the predominance of lymphocytes in peritoneal fluid occurs in fewer than 19% of cases, as opposed to what is seen in non-uremic patients.4

In some tuberculosis cases, as in other granulomatous disease such as sarcoidosis, hypercalcaemia has been observed prior to the appearance of tuberculous peritonitis (up to 6-8 months earlier), which may be explained by the conversion by macrophages of 25(OH)D3 to calcitriol.6 These macrophages are resistant to the feedback mechanism which in normal conditions regulates calcitriol production.7

The limited utility of the tuberculin test (due to cutaneous anergy in patients on RRT)3 and the difficulty of confirming diagnosis through microbacterial culture of peritoneal fluid, limited, among other reasons, by slow growth of the bacillus (up to 4-6 weeks) and the high percentage of false negatives can delay the diagnosis. Ahigh degree of clinical suspicion is needed in those patients with recurrent peritonitis, negative bacterial cultures and persistent clinical symptoms despite antibiotic treatment.

A high percentage of cases are diagnosed through invasive techniques, as in the case described, requiring peritoneal biopsy through a laparoscopy or laparotomy, where macroscopic histological examination is done on the presence of whitish nodes dispersed over the peritoneum.

Treatment of tuberculous peritonitis in patients on peritoneal dialysis is based on experience of treatment for patients with end-stage renal insufficiency and extrapulmonary tuberculosis. Avoidance of ethambutol for these patients is recommended because of the risk of optic neuritis.

According to the 2005 international recommendations, for peritoneal dialysis related infections the treatment should be started with four tuberculostatics for three months and then isoniazid and rifampicin for the nine remaining months of treatment.8

The protocol for removal of the peritoneal catheter is controversial. Although late ultrafiltration failure is seen in a large percentage of patients, there are however, reported cases in whom peritoneal dialysis remain successful which remain successful in peritoneal dialysis. CA125 in peritoneal effluent has been reported as a marker for disease progression.9,10

Mortality from tuberculosis for patients on replacement renal therapy varies between 0.5 and 1%, with these figures rising up to 15% when the cause of death is tuberculous peritonitis, generally due to a delay in diagnosis.5

Table 1. Biochemistry on admission

Table 2. Clinical Findings in Tuberculous Peritonitis at Presentation

Figure 1.