Pregnancy involves an atherogenic lipid profile driven by increased resistance to insulin, oestrogen, progesterone and placental lactogen.1,2 This increase may worsen the underlying hypercholesterolaemia in pregnant patients with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia (HFH).3 Total cholesterol increases by 25–50% and LDL cholesterol (LDL-C) by 50%4 with a predisposition to endothelial damage in the foetus, which begins during intrauterine life, and postnatal susceptibility to arteriosclerosis.5

Therapeutic management and target achievement are complex, since lipid drug therapy is limited by the teratogenic risk and experience with therapeutic apheresis is limited.

We present the case of a 33-year-old woman with HFH diagnosed in 2019 (LDLR gene mutation), with corneal arcus and left Achilles xanthoma. Family history includes a father who died at age 50 from a myocardial infarction and a sister who had a cerebrovascular accident at age 29.

The patient continued with routine follow-up in Endocrinology, with ezetimibe and atorvastatin providing good lipid control. Due to her desire to have children, treatment was changed to colestyramine, with total cholesterol levels of 516 mg/dl and LDL-C of 402 mg/dl during the second trimester of pregnancy then, after a multidisciplinary we were consulted to start LDL apheresis, assessment. The patient had concomitant gestational diabetes.

After obtaining informed consent, under ultrasound and fluoroscopic control (with 1 second of time of fluoroscopy), a right jugular tunnelled catheter was inserted in the 26th week of gestation and LDL apheresis was started, using the double filtration technique.

We used the Plasauto Σ™ monitor indicating 1L as the target volume of plasma to be treated, 30% plasma/blood ratio, 10% drainage/plasma and 10% replacement/plasma, in order to avoid haemodynamic abnormalities and prioritise foetal well-being. After each session, a gestational ultrasound was performed, with no abnormalities observed in the foetus and the in the amount of amniotic fluid preserved.

The frequency of the sessions was based on the calculation of mean LDL-C or Cave (known as time-averaged LDL-C), with the target Cave being <250, with maximum LDL-C of 300 mg/dl. The blood flow used was 100 ml/min and an initial bolus of heparin sodium was administered as the anticoagulant treatment necessary for the technique. The catheter was sealed with 1% heparin.

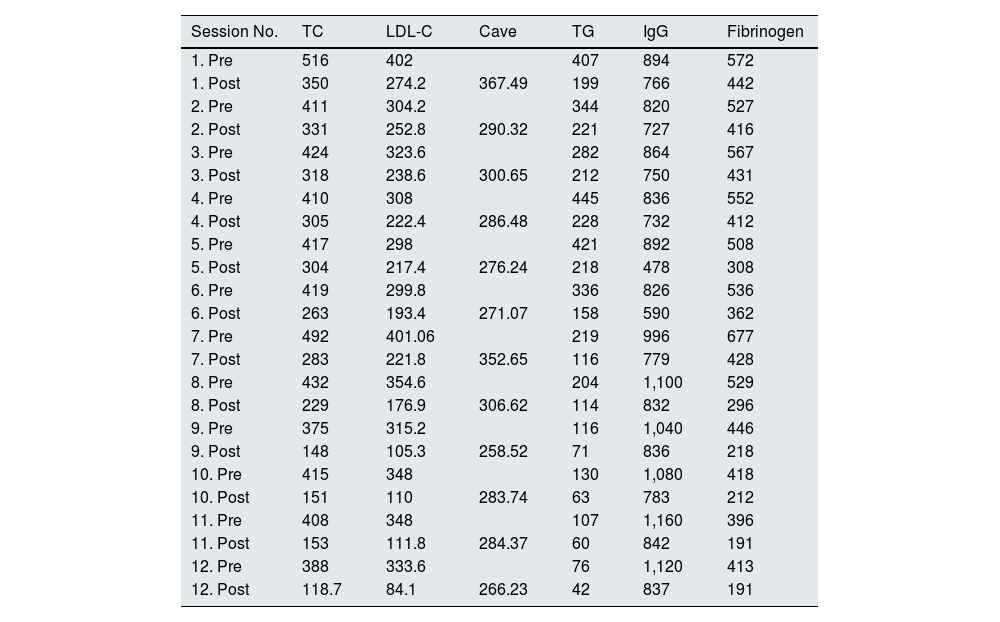

A total of six sessions were carried out during pregnancy and six sessions during the lactation period; after all sessions a decrease in total cholesterol and LDL-C to target values was observed as agreed with the Endocrinology department (Table 1). The sessions were well tolerated clinically and haemodynamically.

Pre- and post-session analytical parameters of LDL apheresis.

| Session No. | TC | LDL-C | Cave | TG | IgG | Fibrinogen |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Pre | 516 | 402 | 407 | 894 | 572 | |

| 1. Post | 350 | 274.2 | 367.49 | 199 | 766 | 442 |

| 2. Pre | 411 | 304.2 | 344 | 820 | 527 | |

| 2. Post | 331 | 252.8 | 290.32 | 221 | 727 | 416 |

| 3. Pre | 424 | 323.6 | 282 | 864 | 567 | |

| 3. Post | 318 | 238.6 | 300.65 | 212 | 750 | 431 |

| 4. Pre | 410 | 308 | 445 | 836 | 552 | |

| 4. Post | 305 | 222.4 | 286.48 | 228 | 732 | 412 |

| 5. Pre | 417 | 298 | 421 | 892 | 508 | |

| 5. Post | 304 | 217.4 | 276.24 | 218 | 478 | 308 |

| 6. Pre | 419 | 299.8 | 336 | 826 | 536 | |

| 6. Post | 263 | 193.4 | 271.07 | 158 | 590 | 362 |

| 7. Pre | 492 | 401.06 | 219 | 996 | 677 | |

| 7. Post | 283 | 221.8 | 352.65 | 116 | 779 | 428 |

| 8. Pre | 432 | 354.6 | 204 | 1,100 | 529 | |

| 8. Post | 229 | 176.9 | 306.62 | 114 | 832 | 296 |

| 9. Pre | 375 | 315.2 | 116 | 1,040 | 446 | |

| 9. Post | 148 | 105.3 | 258.52 | 71 | 836 | 218 |

| 10. Pre | 415 | 348 | 130 | 1,080 | 418 | |

| 10. Post | 151 | 110 | 283.74 | 63 | 783 | 212 |

| 11. Pre | 408 | 348 | 107 | 1,160 | 396 | |

| 11. Post | 153 | 111.8 | 284.37 | 60 | 842 | 191 |

| 12. Pre | 388 | 333.6 | 76 | 1,120 | 413 | |

| 12. Post | 118.7 | 84.1 | 266.23 | 42 | 837 | 191 |

IgG: immunoglobulin G (mg/dl); LDL-C: LDL cholesterol (mg/dl); TC: total cholesterol (mg/dl); TG: triglycerides (mg/dl).

Average LDL cholesterol calculation (Cave): Cave = Cmin + K (Cmax–Cmin).

Cmin = LDL-C immediately after apheresis. Cmax = LDL-C immediately prior to apheresis. K or rebound coefficient = 0.73 (heterozygotes).

In week 35 + 3 of pregnancy, the patient presented with premature rupture of membranes, with eutocic delivery of a male newborn, weighing 2,565 g, measuring 47 cm and Apgar scores of 9 and 10 at minutes 1 and 5, respectively.

In the sessions carried out during the lactation period, the volume of plasma treated was greater (2,500–2,800 cc per session), with all other parameters similar to the procedures described.

After completing the sessions, the tunnelled catheter was removed without incident.

During pregnancy, a detailed assessment of lipid metabolism should be performed in patients with a previous diagnosis of HFH, not only due to the acute complications that may arise, but also because of future cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in the newborn.

Despite the new lipid-lowering drugs that achieve optimal lipid control, their safety profile during pregnancy is inadequate owing to the risk of teratogenesis.6,7 Currently, in the different consensuses, LDL apheresis is considered to be part of the therapeutic arsenal of patients with HFH during pregnancy. The exact reference values for cholesterol during pregnancy are unknown, but the indications for starting therapeutic apheresis in the general population are: LDL-C >300 mg/dl without cardiovascular disease, and LDL-C >200 mg/dl with cardiovascular disease.8,9

Double filtration is an extracorporeal procedure which, subsequent to plasma separation, processes the plasma through a second filter in order to eliminate components according to their molecular weight, such as circulating lipoproteins containing ApoB, mainly LDL-C and Lp(a). The American Society for Apheresis (ASFA) guidelines10 do not describe what the ideal regimen to use during pregnancy should be, and it is important to individualized for each patient and adapt the technique used.

Side effects are rare and mild, and include hypotension, headache, nausea and problems with vascular access, which the patient did not experience, perhaps due to the volumes used during pregnancy.

In conclusion, we report a case of a pregnant woman with HFH controlled with LDL apheresis, which involved a multidisciplinary approach and posed a therapeutic challenge given the lack of consensus documents on the use of this technique in pregnancy. The treatment regimen used is described, which was successful in our experience, with an adequate safety profile.

Key points- -

Familial hypercholesterolaemia can pose a challenge in the therapeutic management of pregnant women.

- -

Double filtration is an extracorporeal procedure that selectively removes atherogenic components from plasma with an adequate safety profile.

- -

Therapeutic lipid apheresis can be considered part of the therapeutic arsenal in the management of familial hypercholesterolaemia in pregnant women.