La calidad de vida relacionada con la salud (CVRS) ha sido ampliamente estudiada en el ámbito de los pacientes en diálisis. Sin embargo, son pocos los trabajos que incluyen las relaciones de variables psicosociales y de adhesión al tratamiento con la CVRS. El objetivo de esta revisión es sintetizar sistemáticamente la información disponible sobre el rol que las variables psicológicas (depresión, ansiedad y estrés) y la adhesión al tratamiento tienen sobre la CVRS de los pacientes en diálisis a través de una revisión narrativa sistemática. Se seleccionaron los estudios que incluyeron y relacionaron en sus resultados variables psicológicas (al menos una de ellas: depresión, ansiedad o estrés percibido), adhesión al tratamiento y CVRS en población adulta en tratamiento con diálisis debido a su enfermedad renal crónica avanzada (ERCA). Los estudios incluidos debían incorporar en su protocolo de evaluación instrumentos estandarizados. Se efectuaron búsquedas en las bases de datos MedLINE y PsycINFO de enero de 2002 a agosto de 2012. Se incluyeron 38 estudios en esta revisión y fueron sometidos a una evaluación de la calidad metodológica. La revisión ha permitido observar que un 100 % de los trabajos identifica una asociación negativa entre indicadores de ansiedad, depresión y estrés con la CVRS, reflejando que dichas variables son factores de riesgo para la calidad de vida. La adhesión al tratamiento ha sido asociada con factores psicológicos y con la CVRS en un 8 % (N = 3) de los estudios incluidos, mostrándose un factor de protección para la calidad de vida en el 66 % de los estudios (2 de 3) que incluyeron la variable adhesión. Considerando el efecto de dichas variables sobre la CVRS, es importante detectar precozmente indicadores de ansiedad, estrés y depresión o dificultades para cumplir con el tratamiento en la población ERCA en diálisis. Esto permitirá intervenir a tiempo antes de que la CVRS se vea mermada.

Health-related quality of life (HRQOL) has been widely studied in the field of dialysis patients. However, there are few studies that include relationships of psychosocial variables and adherence to treatment with HRQOL. The aim of this review is to systematically synthesise available information on the role that psychological variables (depression, anxiety and stress) and adherence to treatment have on HRQOL of dialysis patients through a systematic narrative review. We selected studies that included and related, in their results psychological variables (at least one of the following: depression, anxiety or perceived stress), adherence to treatment and HRQOL in adults on dialysis due to advanced chronic kidney disease (ACKD). The studies included had to incorporate standardised instruments into their assessment protocol. We searched the MEDLINE and PsycINFO databases from January 2002 to August 2012. Thirty-eight studies were included in this review and we assessed their methodological quality. The review revealed that 100% of the studies identified a negative association between indicators of anxiety, depression and stress and HRQL, indicating that these variables are risk factors for quality of life. Adherence to treatment was associated with psychological factors and HRQOL in 8% (N=3) of the studies included and has been demonstrated to be a protective factor for quality of life in 66% of studies (2 of 3) that included this variable. Considering the effect of these variables on HRQOL, it is important to screen for early indicators of anxiety, stress and depression or difficulties in complying with treatment in the ACKD population on dialysis. This will allow preventive interventions to be carried out before HRQOL deteriorates.

INTRODUCTION

The number of individuals with advanced chronic kidney disease (ACKD) is increasing exponentially worldwide every year1, and by extension, the number of ACKD patients who will require renal replacement therapy (RRT) is increasing. Chronic kidney disease prevalence in Spain stands at 11% and with the number of patients who are eligible for RRT increasing 5%-8% per year, these figures mean that this disease is a health, social and economic problem of the highest order2. In 2010, 83.8% of patients who began RRT opted for haemodialysis, 13.6% for peritoneal dialysis and 2.7% for an early transplant3. Moreover, the life expectancy of patients who begin RRT is short and no significant differences have been found between the two dialysis techniques when variables such as age and the presence of diabetes mellitus are controlled4. In short, the dialysis options are not optimal in terms of survival, regardless of the technique chosen. Given this bleak context, we should highlight the impact of an expensive, highly invasive, time-consuming therapy that requires self-care on the patient and their family. This set of factors puts ACKD patients on RRT in a paradigmatic situation for the study of the psychosocial cost of chronic disease5.

ACKD, like many chronic diseases, may be treated but is not curable. This means that nephrology teams must base their healthcare work on managing the objective parameters of cardiovascular risk, diet control and the impacts of uraemia, and subjective parameters, which refer to what patients say about their functional, physical, social and mental condition, as well as the impact that the disease and the treatments have on their lives6. In the sphere of chronicity, these subjective parameters are key when assessing the available treatment options and the quality of psychological adjustment to a disease7 that the patient will have for the rest of their lives. It is clear that medical and pharmacological healthcare is insufficient in the comprehensive care of kidney patients on RRT8. In line with Fukuhara et al.9 claim, if our aim is to provide an excellence-based response, nephrologists must look at not only the objective results, but also, and with the same level of importance being afforded hereto, the thoughts of patients about their state of health and quality of life.

Health-related quality of life (HRQOL) is a multidimensional concept that has been defined as the subjective evaluation that an individual carries out on the impact of the disease and its treatment on their physical, psychological and social dimensions, assessing the impact on their functioning and well-being. According to some experts10, the evaluation of HRQOL should address a minimum of three dimensions: physical, psychological and social, with the domains most commonly studied in the sphere of HRQOL in chronic disease being physical health, body pain, the emotional or affective state, social functioning and mental health11.

In Spain, the development of the research and study of HRQOL in RRT patients dates back to the mid 1990s12. However, the majority of review studies found in the literature focus on the clinical factors that determine HRQOL in each stage of the kidney disease13,14, the validity of instruments used for the assessment of HRQOL15 or the challenges for the nephrology community in this field of study16. In this regard, the empirical studies published mainly report the role of certain sociodemographic (age, sex, employment situation) and clinical or biological variables (comorbidity, certain biochemical parameters [haemoglobin and albumin], years on dialysis and tolerance to the latter) in explaining the variance of HRQOL in renal patients on dialysis17-20.

Psychosocial variables related to HRQOL have not been studied very systematically, with the study of the impact that symptoms of depression have on kidney patients on dialysis being the main subject both in the past21,22 and in the present23,24. Other psychosocial variables that have become important in relation to the HRQOL of dialysis patients have been symptoms of anxiety25, the experience of stress26 and social support27.

Furthermore, recognising the complexity of treatment regimens, and as a result, adherence to treatments, has been described as one of the most common problems faced by both kidney patients28 and dialysis unit staff29. However, although there are studies that relate this variable to quality of life30,31, there is still little scientific evidence that describes the role of adherence to treatment and the psychosocial variables on HRQOL in dialysis patients.

In our review of the literature, we did not find any theoretical study that summarised the role of psychosocial variables and adherence to treatments on HRQOL. Greater efforts must be made in this line of study, beyond continuing to examine the role of depression on HRQOL of kidney patients on dialysis. As such, this study proposes the objective of systematically summarising the information available on the role that psychological variables (depression, anxiety and stress) and adherence to treatment have on the HRQOL of dialysis patients through a systematic non-meta-analytic review.

METODOLOGY: EVALUATION CRITERIA FOR STUDIES IN THIS REVIEW

Type of studies

We selected the studies that included and related psychosocial variables in their results (at least one of the following: depression, anxiety or perceived stress), adherence to treatment and HRQOL. We included the subsamples of the studies that compared dialysis patients. The studies included had to incorporate standardised instruments for measuring variables into their evaluation protocol.

Type of participants

We only included studies with an adult population of over 18 years of age on treatment with dialysis due to ACKD.

Search strategy to identify studies

Searches using English terminology were performed between January 2002 and August 2012 in the following databases: MedLINE and PsycINFO. The search terms we used were as follows: “end stage renal disease”, “chronic kidney disease”, “renal dialysis”, “depression”, “anxiety”, “perceived stress”, “stress”, “adherence”, “quality of life”, “health related quality of life”. The search terms were adapted to each database and included cross-references and combined references of key words. Other sources used were the lists of references of the articles identified.

Selection of studies

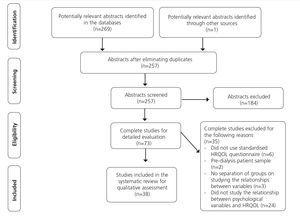

H. G. examined the titles and abstracts generated by the searches. Reference lists from the references of the reviewed articles were also examined, and abstracts followed by the full articles were compiled. The review only includes full-text articles in English or Spanish. As we observe from Figure 1, of the 256 initial non-duplicated abstracts, 71 apparently fulfilled the inclusion criteria for incorporation into the review. Of these 71 articles that were analysed in depth, 35 were excluded for different reasons (Figure 1). The whole process was supervised by E. R. Any doubts and conflicts were resolved together by H. G. and E. R. Lastly, we included 38 studies in this review, covering 38 independent samples that spanned a total of 6997 participants.

Evaluation of the methodology quality of the studies

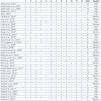

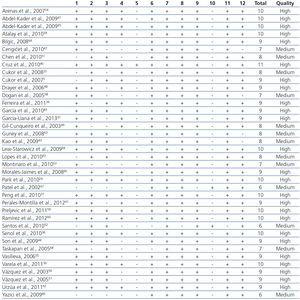

Each of the 38 studies were submitted for an evaluation of the methodology quality according to criteria adapted from the instrument designed by Barra, Elorza-Ricart and Sánchez32. The results are summarised in Table 1 (adapted from the systematic review carried out by Segura-Ortí33).

RESULTS

38 studies met the inclusion criteria. Most studies (16 of 38) focussed exclusively on the role of depression on HRQOL34-49, 14 were studies that evaluated depression and anxiety together on HRQOL50-62, 2 related depression, quality of sleep and HRQOL63,64, and the other studies31,65-69 related different combinations of the variables that are the subject of this review (Table 2).

Furthermore, 24 of the 38 studies included other variables not related to the subject of the review. The variables included were: psychiatric diagnosis25,40,46,48,59,68, symptom burden41,44,65, social support56,57,61,67, sleep quality63,64, sexual function66,69, fatigue36,51, cognitive impairment49,52, beliefs46, neurotic asthenia55, alexithymia50, locus of control50, coping50,61,65, religiousness61,68, suicidal thoughts51, perception of the disease67, life satisfaction67, self-efficacy61, dispositional optimism61 and stressful life events65.

Table 2 summarises the main results of the 38 studies. To facilitate the reader’s comprehension of the table, if the primary source did not display the data of interest, it was calculated from the raw data, but if the data were absent, we included an “a” in the table.

General description of the studies included

Participants

The 38 studies reviewed covered a total of 6997 participants. The study with the lowest number of participants included N=2352, and that with the highest number included N=104755.

Dialysis technique

Five studies exclusively examined peritoneal dialysis patients36,39,50,63,64 and 6 included mixed samples of patients on both dialysis techniques31,41,45,59,65,66. Of the studies, 27 exclusively included haemodialysis patients.

Sex

The patient total included 3405 females and 3592 males. All articles reviewed report the sex of participants in the total samples. In one study, only females participated66 and in another, only males participated35.

Age

The age of participants included in the studies ranged between 18 and 91 years of age. However, 24 studies did not report the age range of their participants.

Duration of dialysis

A common inclusion criterion for most of the studies was that subjects had to have been on dialysis for at least three months. The time on dialysis data display a mean maximum time of 9.1 years54 and a mean minimum time of 1.2 years59. Eight studies did not report the time on dialysis of their participants.

Design of the studies

The studies evaluated were mostly correlations, with the exception of two: one had a pre-post design with a single group39 and another had a longitudinal design48.

Evaluation instruments used

The standardised instruments used by the studies to measure the variables of interest were varied. To measure depression, the instrument most used was the BDI/BDI-II (Beck Depression Inventory) (71% of studies), for anxiety, it was the STAI (State-Trait Anxiety Inventory) (35% of studies), for anxiety and depression combined, it was the HADS (Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale) (35% of studies), for stress, it was the PSS (Perceived Stress Scale) (100% of studies that included this variable) and for adherence to treatment, it was objective clinical parameters and the Morisky Green Levine Test.

Methodology quality

The mean score of the criteria adapted from Barra, Elorza-Ricart and Sánchez32 was 8.5 (out of a maximum of 12). Scores for individual studies ranged from 6 to 11. No study was classified as low quality (1-4 points), 13 were classified as medium quality (5-8 points) and 25 as high quality (9-12 points). The item-by-item breakdown for the methodology quality is shown in Table 1. Only one study40 reported the number of patients who were eligible and/or those initially selected and/or those who accepted and/or those who participated or responded when groups were compared. In none of the studies did it specify in the text whether the loss of participants and/or the data lost was correctly addressed or at least that the quality of the data had been reviewed before statistical analysis. In four studies43,47,58,63 the practical implications of the results with regard to potential benefits for patients were not specified in the discussion.

Description and summary of results according to the variables

Depression

There are 16 studies that evaluate the role of depression on HRQOL. In the 16 samples, prevalence of depression ranged between 25.8%39 and 68.1%35. One study46 found a prevalence of 71.4% of psychiatric disorders measured through a semi-structured interview based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)-IV, of which 20% corresponded to major depression and 10% to dysthymia (dysthymia is an affective disorder of a chronic depressive nature, characterised by low self-esteem and a melancholic, sad and downcast mood, but it does not have all the diagnostic patterns of depression). Sixteen of the 38 studies found that depression decreases HRQOL both in the physical and mental dimensions. As such, depression seems to act as a risk variable for HRQOL. This relationship appears to be strong, since it was observed in 42% of all studies (in 100% of the 16 that analysed this relationship). One study34 found that time on dialysis and depression are directly related. Eight studies found an indirect relationship between depression and physical and mental HRQOL. Only one study41 found this association only in the mental dimension. Of the eight studies that reported multivariate analyses (logistic regression models), five indicated that depression is revealed as a variable that predicts low physical and mental HRQOL; one study38 did not find an association between depression and HRQOL in any dimension; another45 found that depression only predicted low physical HRQOL; and a final study42 found that symptoms of depression contribute to the differences in HRQOL between sexes in favour of males.

Depression and anxiety

We included 14 mixed studies that reported the role of anxiety in HRQOL as well as the role of depression. Only three reported the prevalence of anxiety, with a range from 21%51 to 35.3%50. One study25 found a 71% prevalence of psychiatric disorders measured through semi-structured interviews based on the DSM-IV, of which 45.7% corresponded to anxiety disorders and 40% to mood disorders. One study25 found that anxiety decreases the HRQOL both in the physical and mental dimensions. In the study by Arenas et al.54 they reported that anxiety decreases HRQOL in most COOP-WONCA (World Organization of General Practice/Family Physicians Functional Health Assessment) subscales (except in “changes in health” and “social support”). In both25,54 they confirm the same relationship in relation to depression and HRQOL. In the studies by Chen et al.50, Dogan et al.58 and Prejlevic et al.59 only the role of depression is reported as a risk factor for low HRQOL and not that of anxiety. Eight studies found that both anxiety and depression and physical and mental HRQOL are indirectly related. Of the five studies that reported multivariate analysis (logistic regression models), two50,25 found that both anxiety and depression were variables that predicted low physical and mental HRQOL; two56,60 found that anxiety alone predicts low mental HRQOL, and the final study61 only established one multiple linear regression model for depression, with the latter being a predictor of low physical and mental HRQOL. There are two studies58,61 that, despite including the measurement of anxiety in their variables results, did not study the relationships between anxiety and HRQOL, only focussing on the role of depression or other variables not related to the subject of this review.

Stress

Two studies31,65 evaluated the role of stress on HRQOL. Both concluded that stress and physical and mental HRQOL are indirectly related.

Adherence

Three studies were included in the review that assessed the role of adherence in relation to HRQOL and psychosocial variables such as depression67; depression and anxiety68; depression, anxiety and stress31. Only one study used self-report measurements31 to measure adherence to treatment, while the other two used objective measurements related to biological parameters67,68. The study by Patel et al.67 did not relate adherence to HRQOL in its results. In the other two, it is shown that low adherence decreases HRQOL in the physical dimension31 and in the “vitality” and “social function” subscales67. Likewise, it was found that depression (and not anxiety) decreases adherence68 and that adherence and the physical component of HRQOL are directly related31.

Depression and quality of sleep

Two studies63,64 related depression, quality of sleep (measured by the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index) and HRQOL of patients on peritoneal dialysis. Depression and physical and mental HRQOL were indirectly related in both (that is, as depression increased, HRQOL decreased). Bilgic et al.64 found evidence for depression as a variable that predicts physical and mental HRQOL. Both studies highlight that a poor quality of sleep is a risk factor for HRQOL of patients on peritoneal dialysis.

Depression, anxiety and sexual function

Two studies related depression, sexual function and HRQOL in females on both dialysis modalities66; and depression, anxiety, sexual function and HRQOL in males and females on haemodialysis69. Lew-Starowicz et al.69 found a depression rate of 80.5% in females and 72.7% in males. This rate is the highest in all the studies we reviewed. The instrument used was BDI and the authors noted that most patients had mild (39% of females and 31.8% of males) or moderate depression (31.7% of females and 31.8% of males). Depression and physical and mental HRQOL were indirectly related in both studies (that is, as depression increased, HRQOL decreased). The two studies highlighted that sexual dysfunction is a major risk factor for HRQOL both in females on peritoneal dialysis and in a population of both sexes on haemodialysis.

DISCUSSION

This review highlights that the variables of anxiety, depression and stress negatively affect HRQOL in a large number of studies. Another finding of interest in relation to psychosocial variables is that depression is conceptualised as a risk factor for low physical and mental HRQOL. That is, as symptoms of depression increase, HRQOL decreases. These effects observed in the studies reported were recently confirmed in a major cohort study with 32,332 dialysis patients70, in which depression and low social support explained the variability in the physical dimension of HRQOL and survival. Lastly, both depression and anxiety are the main variables that predict physical and mental HRQOL (in the case of depression) and mental (in the case of anxiety). These results are supported by the study by Kallay et al.71, carried out with dialysis and transplant patients. Studies carried out in our country also note that these two psychosocial variables are the main variables responsible for the differences in HRQOL in males and females in favour of males72.

With regard to the measurement instruments, we can say that the gold-standard for measuring depression is the BDI, used in 20 of the 38 studies. However, only three of them31,43,63 used updated available versions, such as BDI-II. This coincides with authors who indicated that the current strategy in dialysis units of evaluating depression through the BDI has demonstrated its validity and usefulness in this type of patient73. Despite the BDI having shown its usefulness, we should remember that the items that it measures also includes somatic symptoms (energy, appetite and sleep), which could put its applicability in doubt in patients with severe diseases. As such, in this review, we recommend using the CDI (Cognitive Depression Index), composed of 15 of the 21 BDI items when we eliminated the somatic scale. This was the instrument used in the two studies carried out by the Spanish group led by Vázquez56,57. In reference to the anxiety study, there continue to be many doubts over which is the measurement of choice that must be used. Seven studies use the HADS, which has been validated in hospitalised patients. Although it is true that dialysis is a technique that requires constant contact with the hospital, it continues to be an outpatient technique, both as haemodialysis and as peritoneal dialysis, which is also a home technique, and as such, we can question the use of HADS in this type of patient. The appropriate choice of evaluation instrument in this type of multimorbid patient (ACKD) in complex situations is very important, since we are detecting psychological symptoms in which intervention is possible, and as such, an adequate measurement of these symptoms will help us select adjusted treatments. In the case of the STAI, we should remember that STAI-state measurement, according to the original authors, involves a measurement of anxiety that refers to the subjective feelings of tension, apprehension and hyperactivation of the autonomic nervous system while patients respond to the questionnaire74 and does not refer to a stable measurement of anxiety. In the study of perceived stress, it seems clear that the measurement of choice is some versions of the PSS (ten or four items), since it is employed in the only two studies that evaluate this variable in relation to HRQOL31,65. With regard to HRQOL, we can state that the generic instrument of choice is SF-36 (Short Form-36), which is used in 19 studies, and the KDQOL-SF (Kidney Disease Quality of Life-Short Form) is the specific gold-standard employed in 12 of the 38 studies reviewed.

Furthermore, adherence to treatment is directly associated with HRQOL in the physical dimension and in the vitality and social function subscales. That is, the greater the patient adherence to self-report methods and/or objective indicators, the better their physical and social HRQOL and vitality will be. This is confirmed in 100% of the studies that include the measurement of adherence in their variables and relate it with HRQOL. One of the main problems in the study of adherence to treatment is how to obtain a reliable measurement of a complex, multidimensional behaviour with multiple causes that goes beyond taking medical prescriptions into account75. Due to the variability of the measurements used, we were still not able to identify which was the gold-standard76. We only found one study that included self-report markers and objective markers in the assessment of adherence, putting more emphasis if possible when displaying the results on the values reported in the self-report31. What does seem clear in the area of ACKD is that more than one measurement should be used in the evaluation of adherence and that objective measurements used in the biomedical field, such as inter-dialysis weight gain should be significantly related to self-report measurements77. Only three studies31,67,68 included the measurement of adherence along with psychosocial variables and in one of them67, it was not related to HRQOL, and as such, it seems that more effort must be made to try to clarify the role of adherence in HRQOL and the effect that psychosocial variables may have on both markers.

Moreover, we observed a greater prevalence of haemodialysis than peritoneal dialysis. Of the total number of people included in the studies, 29% represented those who used the home technique. In accordance with the studies analysed in this review, we cannot conclude which of the two dialysis techniques results in a higher HRQOL, since this was not one of our objectives. Instead, we can report that, of the six studies that included both dialysis methods, two did not make comparisons between tecnhiques45,59, two others41,64 did not find significant differences in HRQOL between the two methods and one31 of the two remaining studies found differences in physical HRQOL in favour of peritoneal dialysis, and the last found physical and mental differences in HRQOL in favour of haemodialysis66. More effort should be made to clarify the role of dialysis method on HRQOL, because the results do not provide a clear picture.

P. L. Kimmel, a reference author in a psychosocial approach in kidney patients, encourages us to continue studying the role of psychosocial aspects on the adaptation and progression of kidney disease78.

Limitations of the studies evaluated

Although the studies selected had a good methodology quality, it was common to find studies with an incomplete or non-existant35,42-44,47,51-53,55-58,63,64,66-68 description of the sample characteristics evaluated. With regard to the presentation of results, it is striking that several studies40,42,43,45,54,60 did not explicitly report bivariate analysis data amongst their variables (correlations), but did report multivariate analysis results (multiple linear regression models) to predict HRQOL. A more detailed presentation of these indicators may facilitate the potential use of this information in meta-analyses and allow greater clarity on the effect of these variables.

Practical implications

The studies reviewed inform us that depression rates in dialysis units may be around 80.5% and anxiety rates may be above 30%. Anxiety disorders in this population have been underestimated, since they were associated with symptoms of depression, but the reality shows us that they are significant and that it is probably necessary to improve diagnostic procedures in order to detect them effectively25.

This review reflects the availability of standardised evaluation instruments that allow these variables to be measured. The choice of good, reliable and valid evaluation measurements is essential for the correct diagnosis of HRQOL risk factors.

Moreover, it is necessary to bear in mind the patient’s perspective79. This may prove very advantageous for the quality of the research process and allow experts to not become detached from what is important to the patient. For example, the study carried out by Schipper and Abma80 highlighted the main priorities from the point of view from the individual with chronic kidney disease: coping with dialysis (decision-making), family relationships (how they are affected) and dialysis as a stressful experience that interrupts the individual’s life.

Psychological factors are modifiable elements on which we can act with treatment strategies from behavioural science (and/or combined with indicated drugs), in order to boost HRQOL in kidney patients. In XXI century nephrology, it is understood that in dialysis units, we should be capable of detecting, diagnosing and treating anxious-depressive disorders, since we possess interventional tools and programmes that have proven to be effective81. For optimisation, these programmes may be undertaken during dialysis sessions, which is a period of time in which the patient may be more available82. In Spain, the participation of mental health professionals as integrated members of nephrology teams83 is rare, and the development of the specialty (psychonephrology) is still in its infancy. However, the resources of the hospital interclinic model and patient associations are available to us, which are local resources that traditionally incorporate psychosocial support.

Lastly, we must bear in mind that the development of a comprehensive perspective in chronic patient care is increasingly necessary. This gives us an excellent opportunity to create interdisciplinary care, teaching and research teams within the nephrology community that directly impact on the quality of healthcare for kidney patients and their families.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Shire Farmaceuticals, which supported the Nephrology Department’s team in its research activities with an unrestricted grant.

We would also like to thank Solmar Rodríguez (Postgraduate Practicum in Health Psychology, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid) and María Arranz (Undergraduate Practicum in Psychology, Universidad Complutense de Madrid), for their collaboration in evaluating the methodology quality of the studies included in the review.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest related to the contents of this article.

Table 1. Methodology quality of the 38 studies reviewed

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram of the different phases of the systematic review.

11959_16025_61295_en_tabla_2.pdf

Table 2. Main characteristics and results of the 38 studies included in the systematic review