To the Editor:

Apheresis is, in many cases, a first-line a therapeutic option that must be considered in the treatment of certain diseases.

The guidelines of the American Society for Apheresis establish the indications for therapeutic apheresis (TAP) and divide the different pathologies into categories in accordance with the efficacy demonstrated.1,2

Although it is an extracorporeal blood purification technique used daily by nephrologists in dialysis, apheresis therapy is still an undervalued technique that is underutilised by our specialty, perhaps due to a lack of knowledge about its indications or its efficacy.

We present two clinical cases, occurring over the same period, of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) recurrence in renal grafts that demonstrate the pros and cons of plasmapheresis (PP) carried out on time in this type of pathology. In the first case, the patient started PP at the same time in which proteinuria reached nephrotic range, while in the second patient, TAP was performed more than six months later.

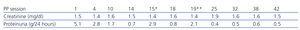

Our first patient is a 32-year-old woman with end-stage chronic renal failure (ESRF) secondary to FSGS on dialysis. She received a renal transplantation with good progress, with creatinine of 1.2mg/dl and proteinuria of 0.3-0.4g/24 hours after three months. From this time, we observed a progressive increase in urine protein, despite intensifying treatment with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers, and she started PP after 5 months with proteinuria of 5g/24 hours and stable renal function. She underwent 1 session/48-72 hours, and we observed a progressive decrease in proteinuria. After 14 sessions, she displayed creatinine of 1.5mg/dl and proteinuria of 0.7g/24 hours. PP was therefore discontinued in order to assess stability. A month later, we again observed an increase in proteinuria to 2.9g/24 hours. We recommenced PP at that time and after three sessions proteinuria decreased to 0.8g/24 hours, with creatinine of 1.6mg/dl. We again had confirmation of a good response when we had to discontinue the session due to cytomegalovirus infection, with proteinuria increasing to 2.1g/24 hours and returning back to its stable state after we recommenced PP. Today, almost four years after transplantation, she is asymptomatic with proteinuria of around 0.4-0.5g/24 hours and creatinine of 1.4mg/dl, with one PP session being conducted per month (Table 1).

Our second patient is a 55-year-old male, also affected by ESRF due to FSGS on dialysis. After transplantation, he showed good initial progress with creatinine of 1.4mg/dl. In the first weeks after transplantation, proteinuria remained around 0.5-0.6g/24 hours, and it was interpreted as having originated in the native kidneys because at the time of transplantation, the patient maintained some residual diuresis. Proteinuria gradually increased and after a month it reached nephrotic range at 5.1g/24 hours. As such, we decided to intensify treatment with dual blockade. Four months after transplantation proteinuria was 12g/24 hours and the patient experienced renal failure (creatinine 2.9mg/dl). Two months later, we decided to begin PP. A total of 13 sessions were carried out, 1 session/48-72 hours. Due to a lack of response, we decided to discontinue treatment (Figure 1).

It has been postulated that primary or idiopathic FSGS is due to a circulating factor present in plasma (glycoprotein), which increases glomerular permeability and induces protein loss.3,4 The justification for TAP is mainly based on the fact that PP has been shown to remove this glycoprotein with an improvement in proteinuria being observed.5

The purpose of this letter is to present to the largest group of medical professionals, mainly our fellow nephrologists, the efficacy of this technique in the treatment of various disorders, in this case the recurrence of FSGS in renal transplants. If we know its indications and advantages, we will be able to treat certain diseases on time, as in one of the cases that we presented.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest related to the contents of this article.

Table 1. Case 1: progression over time of creatinine-proteinuria

Figure 1. Case 2: progression over time of creatinine-proteinuria