Treatment adherence is one of the greatest challenges for medicine in general and Nephrology in particular. Lack of adherence is especially important in those patients with chronic diseases and in those diseases in which a clear association is not observed between taking the drug and the benefit that is obtained. Phosphate (P) binders would be part of this latter drug group, with the added inconvenience that they must be taken with food or immediately after eating, which interferes considerable with the individual's lifestyle and habits. This, along with other reasons we shall discuss, explains how the percentage of non-compliance for P binders exceeds 50% in most studies,1,2 which has a clear repercussion on morbidity and mortality in patients who do not achieve the therapeutic objectives recommended by the clinical practice guidelines.

What are the causes of non-adherence to phosphate binders?Traditionally both treatment regimen complexity (for example, the frequency or amount of tablets to take)3 as well as lack of information and lack of knowledge about the use of the drug have been identified as negatively influencing adherence.4 In this sense, P binders account for more than half of the daily tablets taken by the dialysis patient.5 Patients find it difficult to understand the true importance of high P levels on their survival and morbidity, since there is no direct repercussion between taking the P binder and symptoms. Simplifying the administration regimen and increasing the patient's information are fundamental elements, but only offer a partial solution to the problem.6 One study conducted in a haemodialysis unit showed that patients with high P levels were the ones who best knew the importance of controlling it and the utility of the P binders, which demonstrated that, despite the information, there are other causes of non-adherence.5

There are two types of non-adherence7: 1) Unintentional: the patients do not comply with the treatment because they are unable or do not have the resources to do so. They may forget to take the drug; be unable to buy the prescriptions or go to the hospital to obtain the medication; they may not know how to take it properly (for example: always with food, including “snacks” and not just with the main meals) or how to take it effectively (for example lanthanum carbonate chewed or well ground). These are practical barriers to adherence. 2) Intentional: the patients do not comply because they consciously decided not to do so because of their own beliefs or preferences. These are perceived barriers to adherence. In this case, motivation becomes essential to obtaining appropriate adherence results. This is one of the most difficult challenges to overcome, but we as doctors, are capable to act on it.

In a study conducted on haemodialysis, nearly 25% of patients did not take the medication when they left the house or were with friends, and among the highest risk patient groups were those who had a more active “social life” who were embarrassed or uncomfortable of taking medication when going out.8 Another factor that influenced treatment adherence were the patient preferences. More than 50% of the patients on haemodialysis did not like the P binder that had been prescribed to them, and those who took P binders they did not like had a higher risk of presenting uncontrolled P levels.8 The main reasons they did not like the drug were: gastrointestinal intolerance (stomach upset, diarrhoea, constipation, etc.); bad taste, tablets were too big, difficult to swallow, or chew; preferences for dosage forms different from what was administered to them, etc. (Table 1).

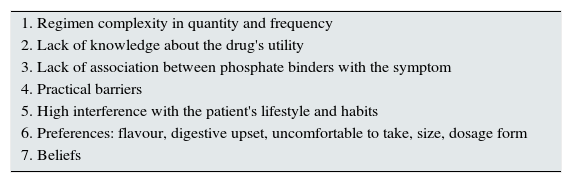

Causes of non-adherence to phosphate binders.

| 1. Regimen complexity in quantity and frequency |

| 2. Lack of knowledge about the drug's utility |

| 3. Lack of association between phosphate binders with the symptom |

| 4. Practical barriers |

| 5. High interference with the patient's lifestyle and habits |

| 6. Preferences: flavour, digestive upset, uncomfortable to take, size, dosage form |

| 7. Beliefs |

Lack of treatment adherence, as deduced from the above, is a problem with a multifactorial origin. Therefore being able to provide an adequate solution in each case requires a certain knowledge about the patient personality and habits: it is essential to personalise the strategies and different professionals have to be involved (physicians, nurses, nutritionists, psychologists, social workers) as a multidisciplinary team that approaches this problem from all the necessary angles.9

First, the healthcare profession should approach and investigate the practice of non-adherence. In clinical practice it is common to evaluate the non-adherence directly and subjectively. However, this approach, when compared with other methods, considerably underestimates non-adherence in patients.10,11 This prevents the identification of many non-adherent patients, with no opportunity to intervene in their behaviour and. In addition, therapeutic approaches with a high degree of empiricism may lead us to unnecessary increase of the drug dosage.

Once non-adherence is identified, the next step is to detect the type of non-adherence, i.e. whether it has to do with practical barriers or perceived barriers. Practical barriers may be relatively easy to identify and resolved. However, the true challenge for professionals comes from those patients who do not comply because they consciously decided not to, due to their own beliefs or preferences. The relationship established between the healthcare professionals and the patients is essential in this type of non-adherence. We have already observed that, although important, it is not sufficient to simplify the treatment regimen or to give scientific information about the drug's utility. It is not enough to repeat to the patient after every blood test that they should take the medication and continue increasing the P-binder dose to obtain the desired therapeutic effect. A higher number of tablets is associated with a worse health-related quality of life (HRQOL) and increasing the number of binder tablets does not seem to improve control and can have the cost of worsening HRQOL.3 Better adherence, better HRQOL.12

The relationship between physicians and their patients is something more than a mere technical act. It is a true human interaction, with the emotional content that goes along with it. To achieve adequate treatment adherence, especially for P binders, the physician should not be limited to the patient's biological aspects (for examples elevated serum P levels), but should also know the environment the patient is in, their habits, their motivations, the way they experience their disease, what are their concerns, the difficulties they face; in short, their values, opinions, expectations, beliefs and preferences: a patient-centred model of communication.13 This creates a climate that encourages them to participate in generating and pursuing a treatment strategy.

The manner how healthcare professionals communicate with patients may encourage motivation, or do the opposite. It is not uncommon to hear patients claiming that they want an “à la carte” treatment. A change is needed, since the professional approaching the patient as an individual with the ability to make decisions may result in improvement of long-term adherence, especially with P binders that interfere significantly with the individual's lifestyle and habits. This personalised “à la carte” treatment, adjusted to the patient's preferences may facilitate the achievement of treatment objectives that may not be accomplished by increasing the dose, simplifying the treatment or educating the patient about the risks of having a poor control of P.

Professionals’ attitudes must be directed to increase patient's motivation to take the medication on their own and helping them to overcome the barriers that the patient may be facing. Education on diets to increase the patient's knowledge about the P content of foods and the “hidden sources” of phosphorus is part of the strategy. Teaching them which foods have a high P content and providing alternatives foods with lower inorganic P content14 will not only encourage treatment compliance, by decreasing the needs for P binders, but will also help to motivate and involve the patient in self care.15

Therefore it is important to change our physician–patient communication model. A discussion with the patient on the convenience to patient's change should be avoided, because this leads to rejection; arguments and attempts to convince the patient tend to cause opposition to the indications, suggestions, or orders needed to achieve a change. This opposition frequently arises if the patient has the perception that his ability to choose is limited and, in general, when his sense of freedom is constrained. Certain attitudes should be avoided, such as: trying to impose a change for “their own good”; implicitly or explicitly suggesting that the healthcare relationship brings an obligation to change; arguing with the patients about not changing; etc. Furthermore, believing in the possibility of changing is an important motivational factor, influencing the ability to initiate and maintain new habits. Having previous satisfactory results reinforces the patient's self confidence in his ability to achieve targets. We will help the patient by analysing with him the results obtained which will enhance their positivity (“It is difficult to take the P binders, but you have done it”). We cannot forget that the patients are responsible for choosing and making the change and we help them if they wish. All these elements are part of the “motivational interview” that has been demonstrated to be effective in improving treatment adherence.16–18

In our haemodialysis unit, we have observed an improvement in treatment adherence versus the prior results in which other measures were used (arguing, insisting, convincing, increasing medication), by taking into account the patients’ preferences. “Intentional” non-adherence fell, going from 38.4% to 23.3%, and it was especially significant in the patient group with the worst P control (P>5mg/dl) which went from 63.6% “intentional” non-adherence to 36.3% (p<0.05) after 24 months, with a significant decrease in the serum P levels [6.63mg/dl (0.98) to 4.45mg/dl (10.12); p<0.05] with a significantly lower number of phosphate-binder tablets [7.76 (3.60) to 5.92 (2.7); p<0.05]. “Unintentional” non-adherence did not show any change, as was also observed in other studies,19 since forgetting occasionally to take a tablet requires other strategies as an approach and likely has a smaller repercussion on P levels. Measuring adherence through questionnaires (SMAQ), with those that also measure “unintentional” non-adherence may explain the differences in results found between non-adherence measured by high P levels and non-adherence measured by specific questionnaires.

ConclusionsLack of treatment adherence in chronic kidney disease patients is a problem of great clinical significance with repercussions on morbidity and mortality; therefore healthcare professionals who care for these patients should pay appropriate attention to detect it. It is necessary to implement a strategy to improve treatment compliance, acting on the clinical and psychosocial factors that interfere in each specific case on treatment adherence. As for improving adherence with P binders, we should act specifically on the treatment complexity, on the patients’ knowledge about the utility of these drugs and dietary P content, but essentially, we should establish adequate physician-patient communication that allows us to learn about the patients’ difficulties, their preferences, their lifestyle and habits. This helps us to choose with the patient the treatment that is best suited to their needs and encourages adherence.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Arenas Jimenez MD, Alvarez-Ude Cotera F. Estrategias para mejorar la adherencia a los captores del fósforo: un reto en la relación médico paciente. Nefrologia. 2016;36:583–586.