Vascular diseases in renal transplant patients are increasing in frequency due to the longer patient survival, the transplantation in older individuals with higher cardiovascular risk, and because many grafts come from donors with expanded criteria.1 Post-transplant hypertension secondary to decreased renal blood flow, either due to involvement of the proximal aorto-iliac segment or the renal artery, is a form of hypertension that can be corrected. Abnormalities of the renal artery anastomosis should be suspected if there is evidence of ischemic nephropathy, resistant renovascular hypertension and claudication of the limb ipsilateral to the renal graft are associated, although all these findings may not always be present.2

We present the case of a kidney transplant woman who after 13 years of transplantation begins with a progressive deterioration of renal function associated with hypertension resistant to the treatment and claudication at a short distance of the left lower limb. The relevant history is polycystic kidney disease and ex-smoking (20 packages/year). On physical examination, she presented a decrease in the temperature of the left foot that appears pale and with absence of distal pulses.

The renal function decreased, serum creatinine increased from of 1.1 to 2.86mg/dl without proteinuria.

Both the abdominal ultrasound and the Doppler ultrasound of the renal graft did not show abnormalities (resistance indices of 0.7–0.8).

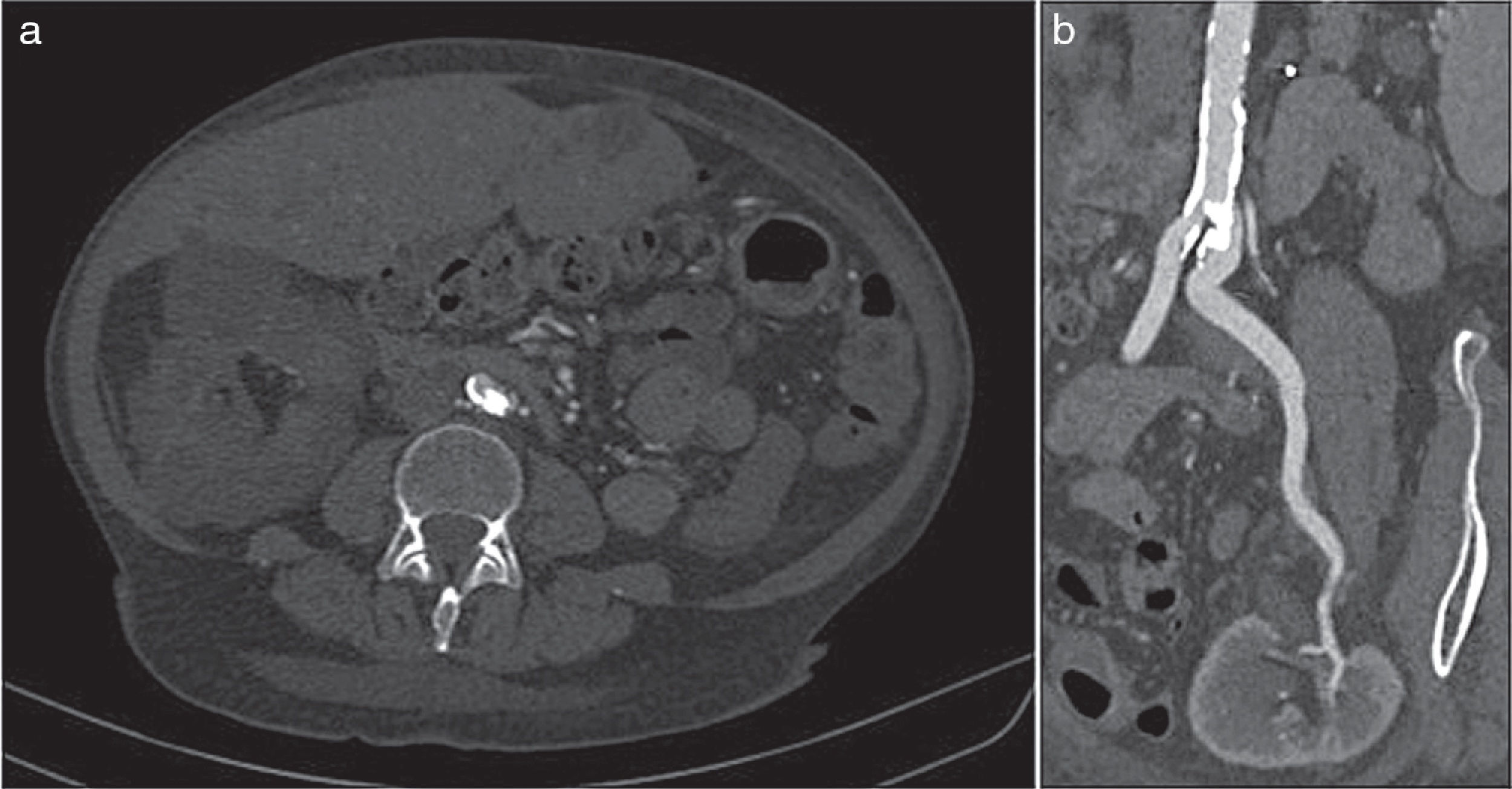

The ankle-brachial index was 0.60 (normal: 0.9–1.2). A CT angiography was requested that showed a large intraluminal calcified lesion (reef coral) that caused a preocclusive lesion at the level of the left common iliac artery, immediately after the aorto-iliac bifurcation. Both the graft artery and the anastomosis and the hypogastric artery were permeable (Fig. 1).

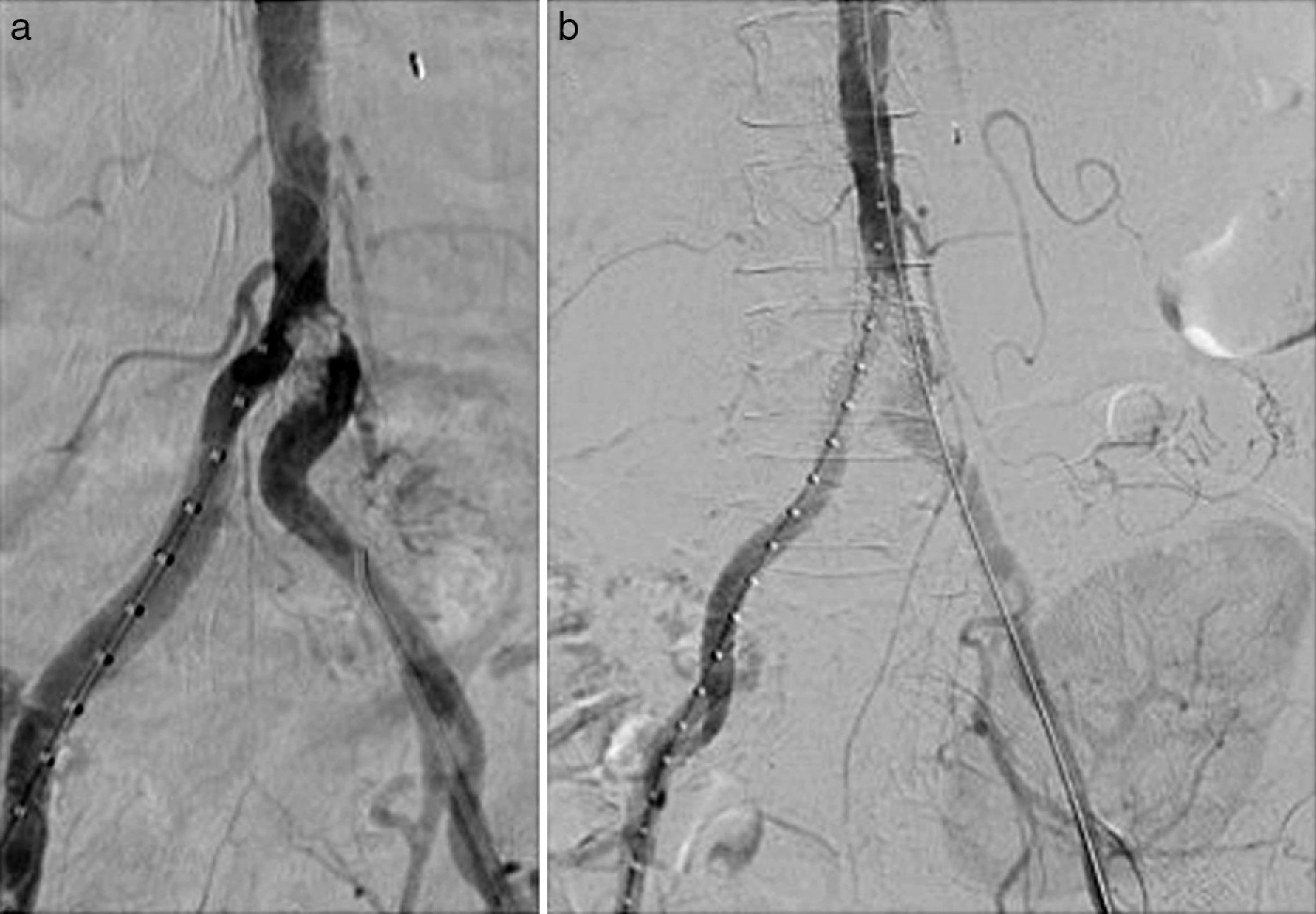

Endovascular treatment by bilateral eco-guided femoral puncture with local anesthesia was performed. An Advanta® V12 8mm×3mm balloon-expandable bilateral stent (Atrium, Hudson, NH, USA) was implanted in the aorto-iliac bifurcation without evidence of residual stenosis in the post-implant control arteriography (Fig. 2). This provision was used in kissing to cover the entire lesion avoiding compromising the ostium of the contralateral iliac axis.

There were no postoperative complications. After 30 days, blood pressure was controlled and renal function improved (serum creatinine was 2.17mg/dl and eGFR by MDRD was 23ml/min/1.73m2). At 6 months, a new CT angiography was performed in which the permeability of the kissing stent persisted without associated lesions.

Causes of renal function deterioration: acute rejection, acute tubular necrosis, pharmacological toxicity and stenosis of the renal artery in its 2 presentations, proximal and distal were ruled out. Due to the development of collateral circulation in the lower limbs the presence of intermittent claudication is not always present3 (in 50% of cases) and several groups highlight the presence of resistant hypertension as the key sign in the diagnosis of stenosis of the proximal aortic-iliac segment.4

Doppler ultrasound is the screening technique of choice to achieve a diagnosis5,6 which should be followed by angio-CT as confirmation test.7

The Doppler ultrasound findings characteristic of arterial stenosis, both in the proximal form and in the renal artery itself, are low intraparenchymal resistance indices and a velocity gradient of 2:18 between the stenotic and prestenotic segments. In our case it was necessary to perform the angio-CT for the definitive diagnosis.

The treatment of choice is percutaneous angioplasty with/without a stent, as long as the stenosis of the renal artery is short and distal to the anastomosis or when the stenosis is located in the iliac artery proximal to the graft.4 Angioplasty is effective in 80% of cases, although a recurrence of 20% has been observed. Surgery is used in complex cases, with arterial kinking, long lesions and stenosis in the anastomosis.

The COBEST study9 is the only prospective, randomized, multicenter trial comparing the use of coated stent versus the free stent in iliac occlusive disease. Their results have shown a significantly greater patency, in the short and long term, in favor of the coated stent versus the free stent in complex lesions classified as type C and D of the TASC II.

Although the use of the coated stent in the aorta-iliac bifurcation is not widespread, some authors such as Sabri et al.10 recommend its use since it provides better long-term patency (92%) than the free stent (62%). It has been seen that the aortic bifurcation coated stent provides greater laminar flow, decreased thrombogenicity, lower probability of plaque prolapse and less hyperplastic tissue growth compared to the free stent.

Endovascular treatment with kissing-coated stents in aorto-iliac occlusive disease is a low-invasive alternative that was effective in our case. After literature review we have not seen any case treated by this technique.

Please cite this article as: Sobrino Díaz L, Mosquera Rey V, Rodríguez García M, Alonso Pérez M, Ridao Cano N, Díaz Corte C, et al. Estenosis de arteria ilíaca tras trasplante renal como causa de hipertensión arterial refractaria y claudicación. Nefrologia. 2018;38:325–327.