Vascular access for haemodialysis is key in renal patients both due to its associated morbidity and mortality and due to its impact on quality of life. The process, from the creation and maintenance of vascular access to the treatment of its complications, represents a challenge to decision-making, because of the complexity of the existing disease and the diversity of the specialities involved. With a view to finding a common approach, the Spanish Multidisciplinary Group on Vascular Access (GEMAV), which includes experts from the five scientific societies involved (nephrology [S.E.N.], vascular surgery [SEACV], vascular and interventional radiology [SERAM-SERVEI], infectious diseases [SEIMC] and nephrology nursing [SEDEN]), along with the methodological support of the Cochrane Center, has updated the Guidelines on Vascular Access for Haemodialysis, published in 2005. These guidelines maintain a similar structure, in that they review the evidence without compromising the educational aspects. However, on the one hand, they provide an update to methodology development following the guidelines of the GRADE system in order to translate this systematic review of evidence into recommendations that facilitate decision-making in routine clinical practice, and, on the other hand, the guidelines establish quality indicators which make it possible to monitor the quality of healthcare.

© 2017 Sociedad Española de Nefrología. Published by Elsevier España, S.L.U.

This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0).

Guía Clínica Española del Acceso Vascular para Hemodiálisis

El acceso vascular para hemodiálisis es esencial para el enfermo renal tanto por su morbimortalidad asociada como por su repercusión en la calidad de vida. El proceso que va desde la creación y mantenimiento del acceso vascular hasta el tratamiento de sus complicaciones constituye un reto para la toma de decisiones debido a la complejidad de la patología existente y a la diversidad de especialidades involucradas. Con el fin de conseguir un abordaje consensuado, el Grupo Español Multidisciplinar del Acceso Vascular (GEMAV), que incluye expertos de las cinco sociedades científicas implicadas (nefrología [S.E.N.], cirugía vascular [SEACV], radiología vascular e intervencionista [SERAM-SERVEI], enfermedades infecciosas [SEIMC] y enfermería nefrológica [SEDEN]), con el soporte metodológico del Centro Cochrane Iberoamericano, ha realizado una actualización de la Guía del Acceso Vascular para Hemodiálisis publicada en 2005. Esta guía mantiene una estructura similar, revisando la evidencia sin renunciar a la vertiente docente, pero se aportan como novedades, por un lado, la metodología en su elaboración, siguiendo las directrices del sistema GRADE con el objetivo de traducir esta revisión sistemática de la evidencia en recomendaciones que faciliten la toma de decisiones en la práctica clínica habitual y, por otro, el establecimiento de indicadores de calidad que permitan monitorizar la calidad asistencial.

© 2017 Sociedad Española de Nefrología. Publicado por Elsevier España, S.L.U.

Este es un artículo Open Access bajo la licencia CC BY-NC-ND (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0).

Vascular access (VA) used to perform haemodialysis (HD) is fundamental in the case of patients with kidney disease and, currently, its influence on morbidity and mortality is no longer questioned. Therefore, due to the great significance it holds for these patients, a Guide on vascular access is needed for use in decision-making during routine clinical practice. This guide should not only collect all the available evidence, but also convey it to professionals in a way which allows daily clinical application.

The first edition of the Sociedad Española de Nefrología (Spanish Society of Nephrology) Vascular Access Guide was published in 2005 with the collaboration of the other societies involved in the current guide. This Guide has been a reference point for professionals working in HD since then. It has become a key document to be consulted in dialysis units and has had a considerable impact on the literature. The current edition aims to renew this Guide, updating all the subjects included in it and adding new concepts that have been raised since its publication.

The format of the current Guide maintains a similar structure, and thus has the same Sections. It is worth mentioning that the topic of “Quality indicators” has now grown to become a section in its own right (Section 7) with 29 indicators, rather than an appendix with only 5 indicators as it was in the previous version. With regard to content, a mixed approach has been preserved, that is to say, on the one hand, recommendations have been derived from the analysis of the current scientific evidence and, on the other, the teaching bent of the previous edition has not been discarded.

COMPOSITION OF THE GROUP DEVELOPING THE GUIDEAfter a meeting in Madrid on 29 June, 2012 representatives of the Sociedad Española de Nefrología (Spanish Society of Nephrology [S.E.N.]), Sociedad Española de Angiología y Cirugía Vascular (Society of Angiology and Vascular Surgery [SEACV]), Sociedad Española de Radiología Vascular e Intervencionista-Sociedad Española de Radiología Médica (Spanish Society of Vascular and Interventional Radiology-Spanish Society of Medical Radiology [SERVEI-SERAM]), Sociedad Española de Enfermería Nefrológica (Spanish Society of Nephrology Nursing [SEDEN]) and in an subsequent meeting of the Grupo de Estudio de la Infección Relacionada con la Asistencia Sanitaria/Grupo de Estudio de la Infeccion Hospitalaria-Sociedad Española de Enfermedades Infecciosas y Microbiologia Clinica (Study Group of Healthcare-related Infection/Study Group of Hospital Infection-Spanish Society of Infectious Diseases and Clinical Microbiology [GEIRAS/GEIH-SEIMC]) took the decision to update the Spanish Clinical Guideline on Vascular Access for Haemodialysis. The multidisciplinary working group was composed of members of the 5 scientific societies involved and the members were chosen for both clinical and research experience in the area of vascular access. During the meeting of the 6 October, 2014, the group took the name Grupo Español Multidisciplinar del Acceso Vascular (Spanish Multidisciplinary Group on Vascular Access [GEMAV]), the name by which the group was to be known thereafter. It was also decided to use the methodological support of the Centro Cochrane Iberoamericano (Iberoamerican Cochrane Center) to systematically review the literature pertaining to the Guide’s clinical questions prioritised by GEMAV. All authors have been involved in the edition of the Guide in a strictly professional way, and have no type of conflict of interest. Some of the authors also carry out some representative tasks for their respective scientific societies. Below are the names of the coordinators of the Guideline, the editors, the members of GEMAV (in representation of the five societies), the external reviewers and the representatives of kidney patient associations.

Coordinators of the Guide

- •

Jose Ibeas. Parc Taulí Hospital Universitari, Institut d’Investigació i Innovació Parc Taulí I3PT, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Sabadell, Barcelona

- •

Ramón Roca-Tey. Hospital de Mollet, Fundació Sanitària Mollet, Mollet del Vallès, Barcelona

Editors

- •

Jose Ibeas. Parc Taulí Hospital Universitari, Institut d’Investigació i Innovació Parc Taulí I3PT, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Sabadell, Barcelona

- •

Ramón Roca-Tey. Hospital de Mollet, Fundació Sanitària Mollet, Mollet del Vallès, Barcelona

- •

Joaquin Vallespín Aguado. Parc Taulí Hospital Universitari, Institut d’Investigació i Innovació Parc Taulí I3PT, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Sabadell, Barcelona

- •

Carlos Quereda Rodríguez-Navarro. Editor of the journal Nefrología for Clinical Practice Guidelines

On behalf of the five societies

S.E.N.

- •

Dolores Arenas. Vithas Hospital Internacional Perpetuo, Alicante.

- •

Pilar Caro. Hospital Ruber Juan Bravo, Madrid

- •

Milagros Fernández Lucas. Hospital Universitario Ramón y Cajal, Universidad de Alcalá, Madrid

- •

Néstor Fontseré. Hospital Clínic, Universitat de Barcelona, Barcelona

- •

Enrique Gruss. Hospital Universitario Fundación Alcorcón, Alcorcón, Madrid

- •

José Ibeas. Parc Taulí Hospital Universitari, Institut d’Investigació i Innovació Parc Taulí I3PT, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Sabadell, Barcelona Secretary of Vascular Access Working Group of the Spanish Society of Nephrology

- •

José Luis Merino. Hospital Universitario del Henares, Coslada, Madrid

- •

Manel Ramírez de Arellano. Hospital de Terrassa, Consorci Sanitari de Terrassa, Barcelona

- •

Ramon Roca-Tey. Hospital de Mollet, Fundació Sanitària Mollet, Mollet del Vallès, Barcelona Official Representative of the Spanish Society of Nephrology. Coordinator of the Vascular Access Working Group of the Spanish Society of Nephrology and of the Spanish Multidisciplinary Group on Vascular Access (GEMAV)

- •

María Dolores Sánchez de la Nieta, Hospital General Universitario de Ciudad Real, Ciudad Real

SEACV

- •

Angel Barba. Hospital Galdakao-Usansolo, Bizkaia

- •

Natalia de la Fuente. Hospital Galdakao-Usansolo, Bizkaia

- •

Fidel Fernández. Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Granada, Granada

- •

Antonio Giménez. Parc Taulí Hospital Universitari, Institut d’Investigació i Innovació Parc Taulí I3PT, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Sabadell, Barcelona

- •

Cristina López. Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Granada, Granada

- •

Guillermo Moñux. Hospital Clínico Universitario San Carlos, Madrid Official Representative of the Sociedad Española de Angiología y Cirugía Vascular (SEACV), Coordinator of the Chapter of Vascular Access of the Sociedad Española de Angiología y Cirugía Vascular

- •

Joaquin Vallespín. Parc Taulí Hospital Universitari, Institut d’Investigació i Innovació Parc Taulí I3PT, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Sabadell, Barcelona Secretary of the Chapter of Vascular Access of the Sociedad Española de Angiología y Cirugía Vascular

SERVEI

- •

José García-Revillo García. Hospital Universitario Reina Sofía, Córdoba

- •

Teresa Moreno. Hospital Juan Ramón Jiménez, Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Huelva, Huelva Official Representative of the Sociedad Española de Radiología Vascular e Intervencionista (SERVEI), Chapter of the Sociedad Española de Radiología Médica (SERAM)

- •

Pablo Valdés Solís. Hospital de Marbella, Málaga

SEIMC

- •

José Luis del Pozo. Clínica Universidad de Navarra, Pamplona Official Representative of the Sociedad Española de Enfermedades Infecciosas y Microbiología Clínica (Grupo de Estudio de la Infeccion Relacionada con la Asistencia Sanitaria/Grupo de Estudio de la Infección Hospitalaria [GEIRAS/GEIH])

SEDEN

- •

Patricia Arribas. Hospital Infanta Leonor, Madrid

- •

David Hernán. Fundación Renal Íñigo Álvarez de Toledo, Madrid

- •

Anna Martí. Consorcio Hospital General Universitario, Valencia Official Representative of the Sociedad Española de Enfermería Nefrológica (SEDEN)

- •

María Teresa Martínez. Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, Madrid

External reviewers

S.E.N.

- •

Fernando Álvarez Ude. Hospital de Segovia, Segovia

- •

Jose Antonio Herrero. Hospital Clínico Universitario San Carlos, Madrid

- •

Fernando García López. Centro Nacional de Epidemiología. Instituto de Salud Carlos III

SEACV

- •

Sergi Bellmunt. Hospital Vall d’Hebron, Barcelona

- •

Melina Vega. Hospital Galdakao-Usansolo, Bizkaia

SERVEI

- •

Jose Luis del Cura. Hospital de Basurto, Vizcaya.

- •

Antonio Segarra. Hospital Vall d’Hebron, Barcelona

SEIMC

- •

Jesús Fortún Abete. Hospital Universitario Ramón y Cajal, Madrid

SEDEN

- •

Isabel Crehuet. Hospital Universitario Río Hortega, Valladolid

- •

Fernando González. Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, Madrid

Kidney patient associations

ADER

- •

Antonio Tombas. President

ALCER

- •

Daniel Gallego Zurro. Council member

Rationale of the Guide edition

The aim of this Guide is to provide orientation in the comprehensive handling of vascular access for patients undergoing haemodialysis. It has been developed in order to provide information and assistance when making decisions in clinical practice. This Guide has been developed as a joint project of the five Scientific Societies referred to above, represented by experienced specialists in this field. The five Societies agreed on the need to update the first edition of the Vascular Access Guide, which was edited by the Spanish Society of Nephrology (S.E.N.) with the collaboration of the other four Societies and published in 2005.

Who is the Guide aimed at

The Guide provides decision-making support for any professional involved in vascular access for haemodialysis. This includes nephrologists, vascular surgeons, interventional radiologists, infectious disease specialists and nephrological nursing. In addition, due to the Guide’s teaching bent, it is also directed at professionals undergoing training in these fields. It has therefore been considered of great interest to synthesise the necessary information for the user to build up the knowledge essential to understand the different aspects included in the Guide. Thus, sections are included with the additional explanations considered appropriate. And finally, it aims to provide a tool for healthcare managers responsible for administration and for health policy. To this end, the indicators section aims not only to provide professionals with the tools necessary to help improve the quality of care, but it also aims to support those responsible for resource management to be able to optimise resources as well as healthcare quality.

Scope of the Guide

The Guide deals with patients with advanced chronic disease either in pre-dialysis or on dialysis who need a VA or treatment of its complications, as well as knowledge related to maintenance and care. The Guide does not include the paediatric population as it understands this group as patients who require a specific approach.

METHODOLOGY FOR THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE GUIDEEstablishment of the Guide development group

The board of the five participating societies, S.E.N., SEACV, SERVEI, SEDEN and SEIMC, approved the selection of the respective experts who were to represent these societies. The coordinators of the Guide consensually selected those responsible for each section, who coordinated the group of experts in these sections, who in turn were members of all the Societies involved. The group consisted of experts in vascular access creation, in the treatment of complications, both surgically and endovascularly, in catheter placement and the treatment of associated complications, in prevention and treatment of infections, in the preparation, monitoring, care and maintenance of the vascular access, in quality indicators and with knowledge of methodology of systematic reviews and evidence-based medicine. The Ibero-American Cochrane Center was asked to provide methodological support to develop the systematic review of the evidence in relation to clinical questions prioritised by GEMAV, and in some other stages in the development of the Guide.

Selection of clinical questions

Firstly, the most relevant clinical questions in routine clinical practice were prioritised, and secondly, recommendations were formulated by applying a systematic and rigorous methodology. For this update, GEMAV selected the most relevant questions from the original guide regarding clinical practice and new questions were added if deemed necessary for the new Guide.

Considering the scope of this Guide, specific clinical questions were identified and a systematic review performed:

- I.

Does the preservation of the venous network prevent complications/facilitate the creation of the arteriovenous fistula?

- II.

In patients with chronic kidney disease, what are the demographic, clinical and analytical parameters in order to determine when the arteriovenous fistula (either native or prosthetic) should be created?

- III.

What criteria are required for arteriovenous fistula planning (based on different types of fistula)?

- IV.

What risk factors have been shown to influence the development of limb ischaemia after arteriovenous fistula creation?

- V.

Can an order of preference be recommended when performing the arteriovenous fistula?

- VI.

Are exercises useful for developing arteriovenous fistulae?

- VII.

What is the minimum maturation time required for a native or prosthetic arteriovenous fistula to be mature enough for needling?

- VIII.

What is the needling technique of choice for the different types of arteriovenous fistula: the three classical ones and self-cannulation?

- IXa.

In which situations is it necessary to indicate antithrombotic prophylaxis after creating/repairing the arteriovenous fistula?

- IXb.

Does the use of antiplatelet agents prior to arteriovenous fistula creation have an impact on patency and reduce the risk of thrombosis?

- X.

How reliable is Doppler ultrasound in determining blood flow in the arteriovenous fistula in comparison to dilution screening methods?

- XI.

Can regulated Doppler ultrasound performed by an experienced examiner replace angiography as the gold standard to confirm significant arteriovenous fistula stenosis?

- XII.

Which non-invasive monitoring or surveillance screening method for haemodialysis arteriovenous fistula presents predictive power of stenosis and thrombosis and increased patency of the prosthetic arteriovenous fistula in the prevalent patient and what is the frequency?

- XIII.

Which non-invasive monitoring or surveillance screening method for haemodialysis arteriovenous fistula presents predictive power of stenosis and thrombosis and increased patency of the native arteriovenous fistula in the prevalent patient and what is the frequency?

- XIV.

What are the demographic, clinical and haemodynamic factors and variables with predictive power of thrombosis in an arteriovenous fistula that presents stenosis?

- XV.

Is there a treatment with better outcomes (percutaneous transluminal angioplasty versus surgery) in juxta-anastomotic stenosis, assessed in terms of patency and/or thrombosis and cost/benefit?

- XVI.

Are there any criteria that indicate in which cases, when and how to treat central vein stenosis, assessed in terms of usable arteriovenous fistula patency and/or thrombosis?

- XVII.

In native arteriovenous fistula thrombosis, what would be the initial indication (percutaneous transluminal angioplasty versus surgery) assessed in terms of patency of the native arteriovenous fistula and/or thrombosis? Does it depend on location?

- XVIII.

In prosthetic arteriovenous fistula thrombosis, what would be the initial indication (percutaneous transluminal angioplasty versus surgery versus fibrinolysis) assessed in terms of patency of the arteriovenous fistula and/or thrombosis? Does it depend on location?

- XIX.

In the presence of stenosis in the native arteriovenous fistula, is there a significant difference between elective intervention and performing treatment after thrombosis?

- XX.

Is there a treatment with better outcomes (percutaneous transluminal angioplasty versus surgery or prosthesis interposition) in non-matured arteriovenous fistula management, evaluated on arteriovenous fistula, which enables it to be used in dialysis, patency and/or thrombosis?

- XXI.

What is the approach to native or prosthetic arteriovenous fistula diagnosed with steal syndrome?

- XXII.

In native and prosthetic arteriovenous fistula pseudoaneurysm, when is surgery versus percutaneous versus conservative management indicated, assessed in terms of severe bleeding complications or death?

- XXIII.

In the high-flow arteriovenous fistula, what therapeutic approach should be taken and what are the criteria (risk factors)?

- XXIV.

In patients who cannot undergo native arteriovenous fistula creation, is the central venous catheter the vascular access of choice versus prosthetic arteriovenous fistula?

- XXV.

Are there differences in the indication to use non-tunnelled catheters versus tunnelled catheters?

- XXVI.

What is the best material and design for a tunnelled central venous catheter?

- XXVII.

Should ultrasound be used as a reference standard for the placement of central venous catheters?

- XXVIII.

What is the best treatment for the persistent dysfunction of the tunnelled central venous catheter (stripping, fibrin sheath angioplasty, fibrinolytics or catheter replacement)?

- XXIX.

What influence do the different types of central venous catheter lumen lock have on its dysfunction and infection?

- XXX.

Is the use of antibiotic prophylaxis justified to lock a tunnelled central venous catheter for haemodialysis?

- XXXI.

Does catheter-related bacteraemia secondary to infection with Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas sp. and Candida spp. force catheter withdrawal and therefore contraindicate antibiotic lock treatment to attempt to preserve the catheter?

- XXXII.

Should empirical antibiotic treatment to cover gram-positive bacteraemia in haemodialysis patients who are tunnelled central venous catheter carriers initially be started with cefazolin (vancomycin if MRSA level > 15%) or daptomycin, associated with the treatment for gram-negatives, when the catheter is preserved?

- XXXIII.

Does the detection and eradication of Staphylococcus aureus in nasal carriers reduce episodes of catheter-related bacteraemia? Is it cost-effective?

The previous recommendations of the former Guideline which have not been substantially updated can be consulted in each section of the Guide and which, therefore, GEMAV has made their own.

Finally, GEMAV identified a series of questions with less impact on clinical practice, but for which the members of GEMAV themselves produced an update based on a narrative review of the literature. These sections can generate recommendations approved by consensus in GEMAV.

Development of clinical questions

These questions have a structured format in order to identify the type of patient, the intervention or diagnostic test to be assessed, the comparisons, where necessary, and the outcomes of interest (PICO format). As detailed in the methodology section, recommendations for these clinical questions have been elaborated in accordance with the GRADE system guidelines.

The working group collaborated in the development of these questions and formatted them to allow the systematic search of the evidence following the routine established by the PICO methodology. That is to say, the initial specification of the type of patient (P), the type of intervention (I), the comparator (C) and the outcome (O) for the questions related to interventions and diagnostic tests. For each question, the group agreed on some systematic review criteria including specific characteristics depending on the design of the sought-after studies.

Classification of the relative importance of the outcomes

For each intervention question, the group compiled a list of possible outcomes, reflecting both the benefits and harm, and alternative strategies. These outcomes were categorised as critical, important or less important in relation to the decision-making process. For example, outcomes associated with important health variables such as mortality in the patient or thrombosis in vascular access were considered critical, and outcomes such as blood flow were pondered less important.

Identification of the clinical questions, recommendations from the previous version of the Guide and narrative updates of the literature

Throughout the document, recommendations relating to clinical questions and updates are marked with the label “new”. Likewise, recommendations corresponding to clinical questions, which were elaborated on the basis of a systematic and rigorous process of formulating recommendations, are identified with the symbol (•). The contents expressed in the rest of the recommendations come from the previous version of the Guide.

Structure of the sections of the Guide

The contents of the guide have been structured in areas of knowledge set out below. In order to coordinate the work in each of them, one or two area coordinators were selected along with some experts, depending on the volume and characteristics of the matter to be analysed. The areas studied, along with the respective coordinators and experts, are listed below.

The current professional activity of the authors of this Guide and a brief summary of their trajectory, which accredits them as experts, are shown in Annex 1.

- 1.

PROCEDURES PRIOR TO VASCULAR ACCESS CREATION Joaquín Vallespín, Fidel Fernández (coordinators), José Ibeas, Teresa Moreno.

- 2.

ARTERIOVENOUS FISTULA CREATION Guillermo Moñux (coordinator), Joaquín Vallespín, Natalia de la Fuente, Fidel Fernández, Dolores Arenas.

- 3.

ARTERIOVENOUS FISTULA CARE Néstor Fontseré (coordinator), Pilar Caro, Anna Martí, Ramon Roca-Tey, José Ibeas, José Luis del Pozo, Patricia Arribas, María Teresa Martínez.

- 4.

MONITORING AND SURVEILLANCE OF ARTERIOVENOUS FISTULA Ramon Roca-Tey (coordinator), José Ibeas, Teresa Moreno, Enrique Gruss, José Luis Merino, Joaquín Vallespín, David Hernán, Patricia Arribas.

- 5.

COMPLICATIONS OF ARTERIOVENOUS FISTULA José Ibeas, Joaquín Vallespín (coordinators), Teresa Moreno, José García-Revillo, Milagros Fernández Lucas, José Luis del Pozo, Antonio Giménez, Fidel Fernández, María Teresa Martínez, Ángel Barba.

- 6.

CENTRAL VENOUS CATHETERS Manel Ramírez de Arellano, Teresa Moreno (coordinators), José Ibeas, María Dolores Sánchez de la Nieta, José Luis del Pozo, Anna Martí, Ramon Roca-Tey, Patricia Arribas.

- 7.

QUALITY INDICATORS Dolores Arenas (coordinator), Enrique Gruss, Ramon Roca-Tey, Cristina López, Pablo Valdés.

The contents of the sections and their importance have been justified in a “preamble”. Subsequently, the “clinical aspects” develop the clinical contents of each section and bring together the recommendations, in the following sections:

- •

Recommendations: each section begins with the compilation of the recommendations, accompanied by a correlative numbering to facilitate identification. As mentioned, the new recommendations are identified with the label “new” and those corresponding to the clinical questions with the symbol (•).

- •

Rationale: discussion on the relevance and rationale of each clinical section.

- •

The clinical questions are identified in a correlative manner with Roman numerals (I, II, III, etc.). For these questions a formal review process of the scientific literature was followed and recommendations were formulated following the GRADE methodology, as detailed below. The section shows a summary of the results collected in the literature review assessed for each clinical question, with an electronic link to the original versions of the reviews. Then in a section called ‘From evidence to recommendation’, a rationale is laid out for the aspects assessed when formulating recommendations and grading their strength, and how agreement was reached among members of GEMAV, which in some situations was achieved through a formal process of voting. Finally, each clinical question is closed with recommendations derived from the assessment of the literature and the rationale process described.

- •

In the case of the updates, a section has been developed where the clinical content of every aspect of interest is described, followed by a table with the recommendations derived from consensus within GEMAV.

Methodology to elaborate recommendations of the clinical questions

As described in the previous section, the update of this Guide was initiated with a process of prioritisation in which the following were identified: a) sections of the original version that would be assumed as its own; b) aspects which GEMAV would update from a narrative review of the literature, and c) clinical questions that would follow a systematic and rigorous process of analysis of the scientific literature. For the development of the different phases, standardised methodological guidelines have been followed, taking as reference the Methodological Manual for elaborating National Health System Guides for Clinical Practice.1

At an initial working meeting two methodologists introduced the clinical members of GEMAV to the theoretical principles used to formulate answerable questions.2 The scope of the contents addressed in the initial version of the Guide was then assessed and these contents were transformed into clinical questions, adding those aspects that GEMAV members considered appropriate. During the meeting and in a subsequent electronic exchange of comments using the Google Drive platform, the most relevant clinical questions that needed to be developed were systematically prioritised, and outcomes of interest for each question were identified.

The clinical questions identify the type of patient, the intervention or diagnostic test to be assessed, the comparisons when necessary and the outcomes of interest (PICO format). Outcomes of interest were defined in order to assess the benefit and unwanted effects of the different procedures and were categorised according to their importance in decision-making.2

Thereafter, exhaustive searches on the clinical questions were made, terminology related to the scope of each question defined, and controlled and natural language identified to recover adequate results from relevant studies in the bibliographic databases. In the case of updates, one methodologist with expertise in the design of exhaustive literature searches designed a search strategy on MEDLINE (accessed through PubMed) and gave the search results to the GEMAV members responsible for each of the sections.

For the prioritised clinical questions an initial search of other Guides, literature reviews and clinical trials was designed to identify those questions with fewer studies to support them and require more exhaustive searches. Subsequently a search strategy on MEDLINE (accessed through PubMed) and The Cochrane Library was designed for each clinical question. In the event that the mentioned study designs were not identified, observational studies were assessed, and if no studies were identified, searches were refined based on networks of citations from relevant studies in ISI Web of Science (Thomson Reuters). The bibliographic search algorithms used in this work can be consulted in the following electronic link. No relevant limits were applied to these algorithms, which were implemented between October 2013 and October 2014. From then up to the date of the edition, the Guide coordinators have carried out a sentinel search task to identify studies that could have a major impact on the recommendations, identifying the last relevant study in April 2016 (clinical question VI).

A structured summary of the results of the most relevant studies was carried out within the scope of each clinical question. For each outcome of interest the quality of evidence was classified according to the standardised criteria defined in the GRADE system. This allows for the establishment of the confidence of the estimators of the effect available in the scientific literature to support the recommendations.3 The quality of evidence can be classified as high, moderate, low and very low. The following factors, which may modify the confidence in the outcomes available in the scientific literature, were considered: risk of bias, consistency between the results of the available studies, the availability of direct evidence, and the precision of the estimators of the effect.3 In the case of observational studies, the following were also taken into account: magnitude of the effect, dose – response relationship, and the potential impact on the results of confounding factors. Each clinical question is accompanied by a summary of findings obtained from the literature review, synthesised at the end of each question in a section called “Summary of evidence”. The summary of findings is accompanied in each case by the classification of the quality of evidence. This process is also contained in summary tables of the results, available for each clinical question in the electronic appendices.

Based on the outcomes of the literature reviews, recommendations were formulated for each clinical question. These may be in favour of or against a particular intervention, and are graded as strong or weak. The strength of recommendations accompanying the questions is reflected by how they are expressed. Hence, strong recommendations are formulated using the expression “we recommend...” or “we recommend not...”, and weak recommendations, or ones where there is more uncertainty, use the expression ‘we suggest...” or “we suggest not...”.

To grade the strength of recommendations, a number of aspects is evaluated. These determine the confidence with which the implementation of the recommendations results in more desirable than unwanted effects for patients.4 The strength of the recommendations is based on a balance between the benefits and risks of interventions, the costs, the quality of evidence, and the values and preferences of patients. Grading the strength of recommendations depends on the more or less favourable and relevant balance among these factors. The recommendations derived from the clinical questions are accompanied by a section called “From evidence to recommendation” in which GEMAV justifies the reasons for supporting a recommendation in a particular way. In exceptional circumstances, where there was insufficient agreement on the clinical questions and the rationale behind the strength of a specific recommendation, a method of consensus by voting was used.5

The recommendations arising from the update sections did not follow a structured process like that previously described. The recommendations corresponding to these sections were formulated by consensus within GEMAV. The contents of the Guide should be updated within a maximum of five years, or sooner if new scientific literature provides relevant data for the current recommendations. In the upgrading process the guidelines of the corresponding methodological handbook will be followed.1

Perspective for users of this Guide. External review

A draft of the Guide underwent external review by 1 to 3 experts selected by each of the scientific societies. A draft was also submitted to the 2 main renal patient societies in the country, ALCER and ADER. Finally, the final text was posted on the websites of the societies for evaluation by members. All comments and suggestions were answered. Both reviewers’ comments and responses are available via the following electronic link.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTThe expert members of each group were independently proposed by each of the societies without receiving any financial compensation.

All experts from GEMAV signed a form declaring any external relationships of a personal, professional, teaching or work-related nature that could have generated conflicts of interest in relation to the contents of this Guide. A summary of these can be found in Annex 2.

All professional societies participated directly in the financing of this Guide. The Spanish Society of Nephrology (S.E.N.), through the Foundation for Assistance to Research and Training in Nephrology (SENEFRO Foundation), received partial and unconditional assistance for the final edition of this Guide from AMGEN, BARD, BAXTER, COVIDIEN, FRESENIUS, HOSPAL, IZASA, MEDCOMP, NOVARTIS and RUBIO. The Spanish Society of Vascular and Interventional Radiology (SERVEI), in addition to its direct financing, also received financial support from BARD. The Spanish Nursing Society of Nephrology (SEDEN) received unconditional assistance from the non-profit Foundation Íñigo Álvarez de Toledo (FRIAT). The other professional societies: Spanish Society of Vascular Surgery (SEACV) and Spanish Society of Infectious Diseases and Clinical Microbiology (SEIMC) participated directly in the financing of this work.

DEVELOPMENT OF THE GUIDELINE SECTIONS1Procedures prior to vascular access creationCONTENTS

- 1.1.

Clinical history

- 1.2.

When to create the arteriovenous fistula

- 1.3.

Pre-operative assessment

Preamble

Nephrology departments must have a clinical care programme for patients with advanced chronic kidney disease (ACKD). This programme should include the provision of detailed information about integrated renal replacement therapy (RRT) systems for patients and family members, and offer the appropriate treatment based on the patient’s clinical characteristics. RRT mode must be finally agreed upon in accordance with the preferences and specific circumstances of each patient.6

The morbidity and mortality of patients on haemodialysis (HD), both before and during RRT, is directly related to vascular access (VA) type. The risk of infectious complications at the start of HD is multiplied by four with central venous catheter (CVC) as compared with native arteriovenous fistula (nAVF) and prosthetic arteriovenous fistula (pAVF). Infections increase sevenfold if CVC is the prevalent VA. Likewise, there is a significant increase in the risk of mortality associated with the use of CVC, especially in the first year of HD.7

Handling the HD patient’s VA is a multidisciplinary task which involves different specialities: nephrology, vascular surgery, interventional radiology, nursing and infectious diseases. The goal is to maintain the highest incidence and prevalence of nAVF.8 But coordination is as important as the work of this multidisciplinary team: it has been shown that efficient management of the team can decrease the prevalence of CVC.9

This first phase, prior to VA creation, is of particular importance, as the patient’s prognosis and illness are, to a great extent, determined by management and the measures undertaken. It is when patients must be informed of the types of RRT available so the most appropriate choice for their circumstances can be made, and strategies to preserve the venous network of upper limbs must be implemented. Likewise, the factors involved in the choice of the ideal access must be determined using oriented medical records and correct pre-operative assessment, and the risk of developing access-associated complications must also be assessed. Finally, the optimal timing for VA creation has to be decided so the need for CVC placement to start HD is minimised, and performing premature interventions should also be avoided.

1.1Clinical historyRecommendations

R 1.1.1) We recommend that all nephrology centres which generate patients for renal replacement therapy have educational programmes, in which a multidisciplinary team participates. The aim of these programmes should be to instruct patients and their families on the different aspects relating to advanced chronic kidney disease, modes of treatment and importance of having an arteriovenous fistula to start haemodialysis

R 1.1.2) We recommend that, in order to select the appropriate type of vascular access, a medical history must be built up, associated comorbidity ascertained and it must be possible to assess the risk factors of failure related to vascular access development, as well as the possible morbidity caused after its creation

- (•)

NEW R 1.1.3) We recommend that extreme care should be taken to preserve the superficial venous network of both upper limbs, which should remain free of needling and cannulations in order to facilitate the creation of an arteriovenous fistula in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease. To this end, it is necessary to instruct healthcare staff and inform the patient

Rationale

There are numerous circumstances associated with ACKD patient comorbidity that can influence the correct development of the VA, which requires prior awareness of all factors involved. During the review of the medical record, all the pathological antecedents that may increase the risk of AVF failure in some way or predispose to the appearance of morbidity related to its creation must be considered.10

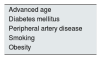

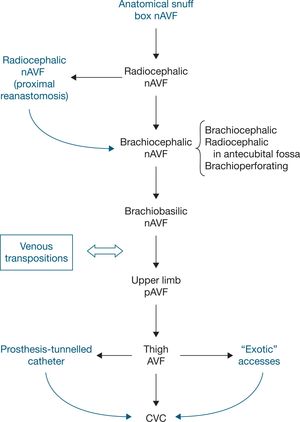

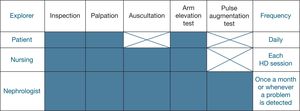

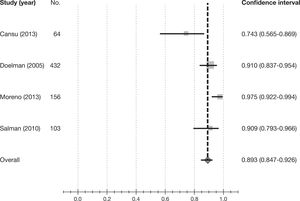

Regarding the antecedents related to the risk of VA failure, firstly, there are the comorbidities associated with a bad prognosis of the VA in general (Table 1): advanced age, diabetes mellitus, peripheral arterial disease, smoking or obesity; and secondly, it is important to consider factors that will determine the optimal location of the arteriovenous fistula (Table 2): previous history of CVC or pacemaker (PM), previous VA, trauma or previous surgery in the arm, shoulder girdle or chest, and previous venous cannulations.10

Local factors to be assessed previously in the indication of the arteriovenous fistula

| History | Associated pathology |

|---|---|

| History of CVC | Presence of central venous stenosis |

| History of PM | Presence of central venous stenosis |

| History of previous VA | Vascular anatomy disorders |

| History of cardiac/thoracic surgery | Presence of central venous stenosis |

| Trauma in arm, shoulder girdle or chest | Presence of central venous stenosis |

| Vascular anatomy disorders | |

| Breast surgery | Existence of secondary lymphoedema |

CVC, central venous catheter; PM, pacemaker; VA, vascular access.

Likewise, a particular underlying pathology, which may be aggravated by the presence of the new AVF, such as heart failure, or prosthetic valves, which may be infected if CVC is used, must be taken into consideration. Moreover, it is important to bear in mind the dominance of the upper limbs to minimise the impact on daily activity, as well as factors like anticoagulant therapy.

Finally, other factors which may affect the election of a given type of AVF should be considered (Table 3). These include life expectancy associated with the patient’s comorbidity, which may advise a more conservative approach by using a CVC, or patients eligible for transplant from a living donor, where a CVC may also be highly recommended.

Other factors determining the choice of vascular access type

| History | Associated pathology |

|---|---|

| Congestive heart failure | Worsening of cardiac function |

| Prosthetic valves | Risk of infection |

| Limited life expectancy | Assess CVC placement |

| Candidate for living donor transplant | Assess CVC placement |

CVC, central venous catheter.

The high prevalence of ischaemic heart disease in HD patients in our setting11 means bearing in mind that both the entire systemic situation and vascular tree of patients undergoing HD is significantly worse than the general population’s. Therefore, strategies must be established to choose the best territory in which to create the VA, taking into consideration the future of the VA and, of course, the patient.

→ Clinical question I Does the preservation of the venous network prevent complications/facilitate the creation of the arteriovenous fistula?

(See fact sheet for Clinical question I in electronic appendices)

| Summary of evidence | |

| No scientific evidence has been found in observational studies or randomised controlled trials in answer to the question on whether venous tree preservation prevents complications or aids VA creation | Very low quality |

| The evidence currently available is based on a review of the bibliography,12 which outlines pre-operative care prior to AVF creation, including vein preservation, as well as group recommendations made in the different published clinical guidelines6,10,13-15 | |

Evidence synthesis development

In order to create an AVF, a suitable vascular bed must be available, both arterial and venous, and the anatomical and functional integrity of both beds is required. Given its deeper location, the arterial bed mainly depends on the patient’s comorbidity and is less exposed to external forms of aggression than the venous bed. As the superficial venous bed may deteriorate and this may have repercussions on the success of the future AVF, the need for measures of protection has to be addressed. The absence of these measures explains why many patients do not have a mature nAVF when they need it to start HD.

The superficial veins of the upper limbs are the most common venous access point in the hospital setting, given the ease of access and safety of the technique. In patients with multiple hospital admissions, this is precisely what causes the venous network to become impaired, as repeated and multiple cannulations produce trauma and the administration of medication provokes an inflammatory response at the vein level (chemical phlebitis).

Despite this, there is no available evidence in the form of observational studies or randomised controlled clinical trials which answers the question of whether the preservation of the venous network prevents complications or facilitates the creation of the VA. Thus, the recommendations made by both clinical practice guidelines (CPG) and the literature are based on the opinions of different groups of experts.12

Most of the CPG in use today,10,13-15 and the literature,16 recommend an aggressive policy aimed at preserving the venous network in HD candidates, through a series of measures prepared to this end (Table 4) and summarised in 2 directives:

Recommendations for preserving the venous network in patients who are candidates for haemodialysis10,13-16

|

CVC, central venous catheter; VA, vascular access.

- 1.

Patient education related to the importance and the measures required to preserve veins in the upper limb.

- 2.

Information and commitment on the importance of vein preservation among healthcare professionals.

From evidence to recommendation

There is no quality scientific evidence to back up an evidence-based recommendation. Therefore, based on good clinical practice criteria, after voting on the recommendation, GEMAV unanimously agreed to formulate a strong recommendation in favour of a strict preservation strategy to preserve the vascular bed, given the clear relationship between its preservation and the viability of the future VA.

Clinical question I. Recommendation

R 1.1.3) We recommend that extreme care should be taken to preserve the superficial venous network of both upper limbs, which should remain free of needling and cannulations in order to facilitate the creation of an arteriovenous fistula in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease. To this end, it is necessary to instruct healthcare staff and inform the patient

Informing the patient about vascular access: when and how should it begin?

Information on HD should include details relating to the VA, the need for its creation, its importance, care and complications. This information must be reinforced in subsequent ACKD check-ups and should be continued when the VA has been created and during the HD programme.17 If a patient has to start HD urgently, he must be informed that a VA is required when this situation is detected. This information will be completed in accordance with their evolution and needs.

Time to start giving information about renal replacement therapy

The optimal time to start RRT requires adequate planning. There is an increased risk of mortality associated with inadequate nephrological care in pre-dialysis and to the use of a CVC as the first VA.18 A lack of organisation at this stage causes greater incidence of starting HD through a CVC with its associated morbidity. If the patient is referred to the nephrologist with enough time, he will receive adequate treatment and preparation from the pre-dialysis phase, as well as information on different RRT techniques: HD, peritoneal dialysis (PD) and kidney transplant (KT). In the Sociedad Española de Nefrología (Spanish Society of Nephrology) agreement document for managing ACKD, the preparation of patients for RRT is based on estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2, if applicable. At this time, in addition to the information about different RRT techniques, the patient should receive VA-related information.19 This appropriate referral implies a lower incidence of complications, especially infections and cardiovascular complications.

RRT should be considered when GFR is < 15 mL/min/1.73 m2 and, in general, dialysis is initiated with an eGFR between 8 and 10 mL/min/1.73 m2, the limit being around 6 mL/min/1.73 m2.19 Expectation of entry into HD is related to the time when detailed information about VA preparation has to be given to the patient. However, the nephrologist’s ability to predict the dialysis commencement is not totally precise and there is a tendency to underestimate the patient’s renal function, which means that HD may begin later than the time estimated.20 This delay is more common in elderly patients, primarily over 85. A number of unnecessary surgical procedures has been shown in this patient group, as they may die before starting dialysis.21 Thus, eGFR on its own may not be sufficient to decide on timing for VA creation.

Informing the patient about ACKD and the various RRT options needs to be coordinated with VA creation. The very creation of the VA may determine the decision to choose HD to the detriment of other techniques, like PD or even conservative management. A systematic review of the timing of the decision-making process of patients and caregivers on RRT22 shows that, from the patient’s perspective, waiting until the final phase of ACKD may not be appropriate. This has important implications, as an unwanted surgical procedure may be performed or the patients perceive that a decision has been taken for them regarding RRT, without their participation. Once the AVF has been created, the patient tends to reject another type of RRT, due to the preference for maintaining the status quo, so this type of treatment is not changed. Therefore, information related to VA creation should be given after the patient has been informed of the various options for RRT and has specifically chosen HD.22

Content and manner of providing the information

At the time of providing information to the patient about the VA, it should be borne in mind that from their perspective, in addition to renal disease and RRT options, the VA is among the main concerns.23 For the patient who needs one, living with an AVF is an important issue as they depend on it and have to provide the necessary care to maintain the access viable. This may generate the feeling of vulnerability, dependence, distrust and it may even become a stigma. Therefore, informing the patient about the need for a VA may generate a pronounced emotional response that should be taken into account.24 Indeed, one of the largest barriers to the creation of the AVF is the actual patient’s refusal.25

Because of all of this, the nephrologist must show particular sensitivity when informing the patient. There are studies which highlight that rejection of AVF creation may be explained by a previous negative experience and the information they receive from other patients and carers may not be well expressed. In addition, it is possible that the information has not been adequately assimilated as it is given at the same time as all the other details relating to entry into HD. Likewise, it is worth pointing out that patients are not usually aware that the use of CVC for HD carries a risk of mortality with it.26 Programmes aimed at helping patients decide which RRT technique to choose mean that patients opting for HD have a significantly higher likelihood of beginning treatment with an AVF.27 This is accomplished by motivating both patient and family from the creation phase to subsequent care. Moreover, the participation of other patients in the orientation of new patients can be of benefit. It has been shown that more patients with AVF recommend this VA than those who use a tunnelled CVC.28

Finally, when providing the patient with all the necessary information on VA, as well as the different forms of RRT, the nephrologist should give information about the different types of definitive VA and their characteristics (nAVF, pAVF and tunnelled CVC). The advantages and drawbacks of each one should be explained, highlighting the fact that the tunnelled CVC is not an acceptable alternative to AVF, if the latter is possible, given its high association with morbidity and mortality (section 6). The risks of tunnelled CVC should be systematically explained, making it clear that CVC is only indicated as a temporary measure pending AVF creation or when it is impossible to create one.

Ethical-legal considerations

Some literature reviews propose that there may be legal implications, in addition to ethical issues, if severe complications of tunnelled CVC arise in a patient who may be eligible for an AVF. In this context, in the same way as the patient signs a consent form before the surgical procedure, some groups suggest that this should be done before inserting the tunnelled CVC, and all the risks agreed to.29

1.2When to create the arteriovenous fistulaRecommendations

- (•)

NEW R 1.2.1) We recommend that the creation of vascular access be considered in patients with progressive chronic kidney disease when eGFR is less than 15 mL/min/1.73 m2 and/or when estimating that dialysis will be needed in 6 months

- (•)

NEW R.1.2.2) We recommend that a native arteriovenous fistula be created 6 months before the start of haemodialysis

- (•)

NEW R. 1.2.3) We suggest that prosthetic arteriovenous fistula be created 3 to 6 weeks prior to the initiation of haemodialysis

- (•)

NEW R.1.2.4) We recommend an arteriovenous fistula be created as a priority in patients with rapid chronic kidney disease progression, lack of arteriovenous fistula maturation and non-tunnelled central venous catheter carriers

→ Clinical question II In patients with chronic kidney disease, what are the demographic, clinical and analytical parameters in order to determine when the arteriovenous fistula (either native or prosthetic) should be created?

(See fact sheet for Clinical QUESTION II in electronic appendices)

| Summary of evidence | |

| Early referral to the nephrologist of patients with ACKD to prepare the AVF improves the success rates of initiation of HD using a mature AVF | Very low quality |

| Planning for AVF creation should be determined by the rate of reduction of renal function in the patient from ACKD stage 4: eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2, after being adjusted for age, gender and body surface area and possible comorbidities | |

| Indication to start dialysis is at level of GFR < 10 mL/min/1.73 m2 or higher if there are other factors which recommend an earlier commencement | |

Evidence synthesis development

For the patient with ACKD it is very important to have a functional AVF when starting HD to avoid the use of CVC and its associated comorbidity. This requires careful planning of its creation.

There are no clinical trials, only observational studies designed to determine when a definitive VA should be created. Recommendations in clinical guidelines are based on this type of studies and experts’ opinions and the proximity of HD is established according to levels in the decline in renal function. They highlight the importance of using these parameters adjusted for age, gender and body surface area. There are 6 CPG that assess the appropriate timing for VA creation in the literature review.6,10,13-15,30

Clinical practice guidelines recommendations

The previous edition of this guide, as well as the Japanese and Canadian guidelines, consider that the VA should be created when eGFR is less than 20 mL/min/1.73 m2. KDOQI (Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative), European and British guidelines recommend VA planning when eGFR falls below 30 mL/min/1.73 m2. The recommended minimum time elapsed between the creation of VA and the beginning of dialysis varies. The Spanish guidelines recommend 4 to 6 months; KDOQI and European guidelines, between 2 and 3 months; British guidelines, between 3 months to one year and Japanese guidelines, between 2 and 4 weeks. They all recommend assessing the earliest possible VA creation when ACKD evolves rapidly, there is VA failure and in patients with a CVC. They all agree that as the pAVF takes around 3 weeks to mature, it has to be created at least 3 weeks before initiation of HD. Finally, CVC does not require specific preparation, except that needed for the placement procedure itself, as it is for immediate use.

Available evidence

The latest review of clinical guidelines still fails to bring to light clinical trials, only observational studies. These publications emphasise the need for early referral to the nephrologist to guarantee adequate information on the various aspects of RRT and the possibility of starting HD with an AVF. Different observational studies made in recent years present data on how influential and important the time taken to refer the patient to the nephrologist and surgeon is regarding the appropriate moment to construct the VA.10,13-15,30

These observational studies show there is a direct relationship between the length of time in the care of a nephrologist and the significantly higher number of AVF created prior to the initiation of HD. This time period ranges from 431,32 to 12 months33,34, passing through 6 months.35,36

However, there have been changes in the latest recommendations for starting RRT. In recent years these criteria have evolved from higher levels of eGFR, > 15 mL/min, to much lower values approaching 5 mL/min. After the publication of clinical trials showing not only the lack of benefit, but even a higher morbidity with the early initiation of dialysis,37-39 the KDIGO guidelines40 (Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes) suggest that HD should be started when clinical symptoms of terminal CRF (chronic renal failure) are visible, seen with eGFR ranges between 5 and 10 mL/min/1.73 m2. In the agreement document for managing ACKD produced by the Sociedad Española de Nefrología (Spanish Society of Nephrology), RRT is considered when GFR is < 15 mL/min/1.73 m2, although an earlier start may be considered if there are symptoms of uraemia, hyperhydration, hypertension difficult to control, or a worsening nutritional status. In general, dialysis is initiated when GFR is between 8 and 10 mL/min/1.73 m2 and would be mandatory if eGFR was < 6 mL/min/1.73 m2, even in the absence of uraemic symptoms.19 However, in patients at risk, an early start for HD should be considered on a case-by-case basis.

From evidence to recommendation

In the absence of clinical trials or observational studies addressing criteria related to timing for VA creation and clinical trials addressed to HD commencement, GEMAV put this recommendation to the vote. It was thought appropriate to consider 2 options. For the first option—when eGFR drops below 15 mL/min and/or estimation of entry at 6 months—there were 15 votes, and for the second option < 20 mL/min and/or estimation of entry at 6 months there were 2 in favour and 3 abstentions. Therefore, considering that three quarters were clearly in favour of one of the options, the working group decided to formulate as a strong recommendation that the creation of the definitive VA should be requested when eGFR ≤ 15 mL/min, or with an estimation of entry into dialysis lower than 6 months.

Patients with rapid CKD progression, with a non-matured AVF or a non-tunnelled CVC should be given priority.

As pAVF take between 3 to 6 weeks to mature (except in those with immediate needling), we suggest this be the time period required for creation prior to the planned HD commencement (section 3).

Clinical question II. Recommendations

R 1.2.1) We recommend that the creation of vascular access be considered in patients with progressive chronic kidney disease when eGFR is less than 15 mL/min/1.73 m2 and/or when estimating that dialysis will be needed in 6 months

R.1.2.2) We recommend that a native arteriovenous fistula be created 6 months before the start of haemodialysis

R. 1.2.3) We suggest that prosthetic arteriovenous fistula be created 3 to 6 weeks prior to the initiation of haemodialysis

R.1.2.4) We recommend an arteriovenous fistula be created as a priority in patients with rapid chronic kidney disease progression, lack of arteriovenous fistula maturation and non-tunnelled central venous catheter carriers

Recommendations

- (•)

NEW R 1.3.1) When planning the vascular access, we suggest decisions not only be based on isolated clinical characteristics, socio-demographic factors, or any risk prediction model. We recommend that the decision be based on a global assessment of clinical history, physical examination of the vasculature, pre-operative ultrasound and patients’ individual preferences

R 1.3.2) We recommend that, during arterial physical examination, peripheral pulses be assessed, the Allen test performed and brachial arterial pressure be taken. During venous physical examination, we recommend the presence of a visible candidate vein be identified after tourniquet placement, with a superficial trajectory in the subcutaneous tissue and absence of significant tortuosity

- (•)

NEW R 1.3.3) We recommend vascular mapping with ultrasound be routinely performed prior to vascular access creation. The ultrasound must evaluate the diameter and the quality of the arterial wall as well as the anatomy and patency of the deep and superficial venous system of the limb

- (•)

NEW R 1.3.4) In patients at high risk for ischaemia (diabetics, age>60 years, presence of peripheral arterial disease, female gender), we suggest the prioritisation for distal arteriovenous fistulae and end-to-side anastomosis, avoiding large anastomoses (> 7 mm). We recommend close clinical monitoring of these patients to detect early signs of ischaemia

Rationale

An important factor to consider in choosing the ideal VA location is the influence that this location will have on subsequent accesses. The surgeon must plan a long-term strategy for possible future access locations. Despite the absence of randomised clinical trials (RCTs) on the order to be followed in access creation, there is general consensus among different groups10,23,24 that access location should be as distal as possible, thereby allowing the creation of further VA in the same limb in the future. The VA should preferably be created in the non-dominant limb to maintain patient’s comfort. Furthermore, the creation of nAVF with preference to pAVF is recommended, although individual conditions may suggest a different approach.

Patient assessment must include a detailed clinical history to identify risk factors for early failure and lack of maturation of the nAVF. It is also necessary to perform a physical examination to detect limitations in joints, motor or sensory deficits, thickness of the skin and subcutaneous fat, limb oedema, presence of collateral circulation in the arm or shoulder, scars or indurated veins.

Physical examination must include pulse palpation to assess presence and quality, including the Allen test, measurement of blood pressure in both upper limbs and the examination of the venous system by palpation with and without tourniquet41 (Table 5).

Clinical criteria required in physical examination for AVF creation1

| Venous examination |

| Cephalic vein visible after tourniquet placement |

| Superficial venous pathway visible and/or palpable in subcutaneous tissue |

| No significant tortuosity |

| Arterial examination |

| Radial pulse easily palpable |

| Permeability of the palmar arch (Allen test) |

| No difference in SBP > 15 mmHg between both upper limbs |

SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Complementary examinations should be performed as a necessary and indispensable aid to define what strategy to follow when deciding which order to choose for VA creation.

→ Clinical question III What criteria are required for arteriovenous fistula planning (based on different types of fistula)?

(See fact sheet for Clinical question III in electronic appendices)

| Summary of evidence | |

| A meta-analysis of three RCTs including 402 patients, as shown later, finds that there was a non-statistically significant difference in achieving AVF success in patients studied with ultrasound mapping in addition to physical examination | Low quality |

| In VA planning, evidence from clinical series is not conclusive enough to make a recommendation about the use of isolated clinical or socio-demographic factors, nor about the validity of specific multivariate models to predict the probability of VA success | Low quality |

Evidence synthesis development

1.3.1 The role of Doppler ultrasound in arteriovenous fistula planning

Since its incorporation into daily clinical practice, different publications have attempted to determine the usefulness of Doppler ultrasound (DU) in the pre-operative assessment of VA candidates.

According to a review by Ferring et al.,42 in order to assess a suitable place for AVF surgery, physical examination must initially be performed in all patients, reserving pre-operative (DU) for certain cases: patients with poor physical exam (obese, no pulses, multiple previous surgeries on the limb), patients with possible arterial disease (elderly, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases) or in patients with possible venous disease (previous cannulation).

Later, Wong et al.43 published a systematic review of the literature, based on the three RCTs published to date on the systematic use of pre-operative ultrasound mapping.44-46 Two of the articles showed the systematic use of pre-operative DU was significantly beneficial, while in the third no benefit in terms of effective access use was shown to carry out HD. The authors conclude that the review suggests positive results in patients who underwent ultrasound mapping prior to VA creation, which may improve long-term patency rates.

Besides the reviews assessed while preparing the recommendations in this section, other more recently published systematic reviews have shown non-uniform results. Although a meta-analysis of five clinical trials suggests that the routine preoperative use of DU is beneficial47 in line with the publication by Wong et al.,43 a systematic Cochrane review48 emphasises that using preoperative imaging does not improve AVF outcome and that new studies with a better design are needed to confirm the result.

1.3.2 Vessel diameter as a criterion for arteriovenous fistula planning

Several studies have tried to determine the ultrasound parameters that may predict AVF outcome.16,42,49-51 Some degree of correlation has been found between the following ultrasound parameters and AVF function: diameter of the artery, presence of arteriosclerosis (measurement of intima/media thickness), flow characteristics at artery level (resistance index after reactive hyperaemia, peak systolic velocity), vein diameter and venous compliance.52

Among these, the parameter most widely documented and in which a higher level of evidence has been found as predictor of AVF function is the inner diameter of artery and vein measured by DU.53-59

Several articles have published series trying to document the minimum diameter of the artery and the vein associated with good AVF prognosis (Tables 6 and 7).49,53-58,60-63

Minimum arterial diameter and prognosis of arteriovenous fistula

| Author | Year | Location | Number of cases | Parameter assessed | Diameter (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lauvao et al.53 | 2009 | Wrist and elbow | 185 | Functional primary patency | Without predictive value |

| Glass et al.54 | 2009 | Wrist | 433 (meta-analysis) | Functional primary patency | 2.0 |

| Khavanin Zadeh et al.55 | 2012 | Wrist and elbow | 96 | Maturation | — |

| Parmar et al.56 | 2007 | Wrist | 21 | Immediate success | 1.5 |

| Korten et al.57 | 2007 | Wrist | 148 | Primary patency | 2.1-2.5 |

| Malovrh60 | 1998 | Wrist | 35 | Early failure | 1.5 |

| Wong et al.58 | 1996 | Wrist | 60 | Early failure | 1.6 |

| Silva et al.61 | 1998 | Wrist | 172 | Primary failure | 2.0 |

Minimum venous diameter and prognosis of arteriovenous fistula

| Author | Year | Venous diameter (mm) | Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glass et al.54 | 2009 | 2.0 | Wrist |

| Lauvao et al.53 | 2009 | 4.0 | Wrist and arm |

| Hamish et al.62 | 2008 | 2.0 | Wrist and arm |

| Smith et al.49 | 2012 | 2.0 | Wrist and arm |

| Wong et al.58 | 1996 | 1.6 | Wrist |

| Malovrh60 | 1998 | 1.6 | Wrist |

| Silva et al.61 | 1998 | 2.5 | Wrist |

| Ascher et al.63 | 2000 | 2.5 | Wrist |

1.3.3 Patient comorbidity as a criterion for arteriovenous fistula planning

There is considerable evidence of the influence of underlying pathology, comorbidities and the patient’s own parameters on the prognosis of the VA to be created.42,49,59

Advanced age

The available evidence suggests VA prognosis is considerably worse in older patients.64 The authors suggest that distal AVF should be avoided in the elderly.

Female gender

Contrary to general opinion and to some authors,65 the best available evidence does not demonstrate that female gender is a risk factor for AVF prognosis66; this is attributed to the small diameter of vessels found in female patients.

Diabetes

Different prospective series show the negative effect of diabetes on AVF prognosis, having less impact in proximal AVF.67,68

Hypotension

Evidence from prospective series suggests a negative effect of sustained hypotension in the prognosis of AVF due to an increased risk of access thrombosis.69,70

Smoking

Smoking has been associated with a worse AVF prognosis in published prospective studies.71-73

Obesity

While a worse prognosis in obese patients with Body Mass Index (BMI) > 30 has not been proved, the evidence available suggests that obesity with a BMI > 35 is a risk factor in AVF prognosis.74

Other factors

Several studies have tried to determine the influence of other factors in access prognosis. These factors are considered to have a minor impact, either due to the lack of clinical evidence (use of systemic heparin during surgery, type of anastomosis, suture technique), or because despite the importance they have shown in limited studies, there is a need for further studies to demonstrate their usefulness in clinical practice (intra-operative heparin dose, use of transdermal nitrates, range of distribution of red blood cells).42,49,59,75-77

1.3.4 Models/rules to predict arteriovenous fistula failure

Using data from 422 patients, Lok et al.78 developed a rule for predicting the risk of AVF failure. They found that poor prognosis factors include age ≥ 65 years, peripheral vascular disease and coronary heart disease, while being Caucasian was a good prognostic factor. These data were used to elaborate a classification of risk of AVF failure.

Despite the acceptable predictive capability shown in this study, there have been no subsequent studies to confirm its clinical usefulness; in fact, it has been questioned by other studies.79

1.3.5 Determining factors for the success of a prosthetic arteriovenous fistula

Rosas et al.80 found some factors of poor prognosis: presence of vascular claudication, number of previously implanted grafts, dialysis dependence at the time of surgery and the use of vascular clamps during the procedure. On the other hand, the use of the brachial artery and the axillary vein, acute-angle anastomosis and grafts of a specific brand (Gore-Tex®) were factors suggesting favourable prognosis.

From evidence to recommendation

The introduction of portable DU in the pre-operative examination of AVF candidates has undoubtedly helped professionals to decide when to create an AVF.

DU has proved to be an essential tool in those units where it is available because it provides a reliable image plus haemodynamic information on the vessels in the pre-operative evaluation.

The progressive increase in the age of patients candidates to arteriovenous fistula creation, with the resulting increase in associated comorbidities, as well as the high prevalence of obesity, often make it difficult to carry out a complete physical examination in these patients, so essential information required to create the AVF is missing (Table 5). In these cases, both clinical practice and the available evidence unanimously recommend the use of DU as the imaging test of choice, before requesting other radiological examinations (phlebography, magnetic resonance imaging).16,42,81,82

However, there is no unanimity in the available literature regarding DU use in patients with a favourable physical examination. There are studies documenting that routine pre-operative ultrasound increases VA patency.10,44,46,47,49,65,83 However, in most of these reports the benefit does not reach the level of significance needed to make a recommendation about the generalised use of DU.42,43,45 Thus, in fact, these authors do not recommend the routine use of DU because it has no proven benefits, both because of the delay other tests may cause and because of the possibility of ruling out AVF creation in vessels with borderline diameter. In contrast, the reasons given in favour of its routine use include the reduction in the number of unnecessary surgical interventions due to low vessel size, no creation of AVF with poor venous drainage, the detection of subclinical arterial disease and the better use of the available vascular bed.

This last point, together with the trend described in the literature, was the main argument which led GEMAV to unanimously decide to recommend the systematic use of DU in the pre-operative examination of all candidates for AVF. It allows physicians to non-invasively obtain a map of a patient’s entire venous capital during the pre-operative evaluation, thus allowing them to decide on the location of the VA bearing in mind the real options for future accesses.

During this examination, the diameter and quality of the arterial wall, as well as the anatomy and patency of the limb’s superficial and deep venous system, must be assessed by creating a map of the aforementioned venous capital of the patient.16,42,52,81,82,84

Current evidence does not allow for a recommendation regarding the minimum diameter of vessels to be used for the AVF; the decision whether the vein or artery should be considered apt for AVF creation must be taken in accordance with diameter – basically, the bigger the diameter, the better the prognosis – and with the available VA alternatives. In any case, in accordance with published articles, arteries < 1.5 mm and veins < 1.6 mm in diameter, following placement of a proximal tourniquet, are considered of dubious feasibility.

Finally, although the prognostic factors in each case should be taken into consideration, it is suggested that the VA location not be decided by taking into account any isolated clinical or socio-demographic factor, or any specific multivariate risk prediction model. It is recommended that the decision be based on a global assessment of each patient’s medical history, physical vascular examination, pre-operative DU and on their individual preferences.

Clinical question III. Recommendations

R 1.3.1) When planning the vascular access, we suggest decisions not only be based on isolated clinical characteristics, socio-demographic factors, or any risk prediction model. We recommend that the decision be based on a global assessment of clinical history, physical examination, pre-operative ultrasound and patients’ individual preferences

R 1.3.3) We recommend vascular mapping with ultrasound be routinely performed prior to vascular access creation. The ultrasound must evaluate the diameter and the quality of the arterial wall as well as the anatomy and patency of the deep and superficial venous system of the limb

→ Clinical question IV What risk factors have been shown to influence the development of limb ischaemia after arteriovenous fistula creation?

(See fact sheet for Clinical question IV in electronic appendices)

| Summary of evidence | |

| No systematic reviews or RCT have been found in the evidence review. The evidence is based on CPG and prospective and retrospective observational studies | |

| In the study by Rocha et al.85 on a population of largely elderly patients, the relationship between steal syndrome and coronary artery disease and peripheral vascular disease was not evident. Female gender was associated with increased risk of ischaemia. However, these are two comorbidities significantly associated with diabetes, which was an independent predictor of steal syndrome. Diabetes is the most important risk factor for the development of VA-associated ischaemic syndrome. Age, AVF type, duration of renal replacement therapy and factors involved in endothelial damage were not significantly associated with steal syndrome. The results highlight the need for careful AVF monitoring, particularly among women and diabetics. The preferential use of end-to-side anastomosis is recommended in the surgical approach | Low quality |

Evidence synthesis development

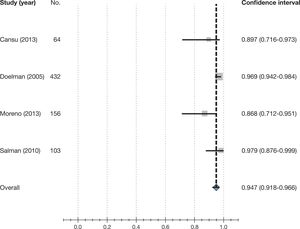

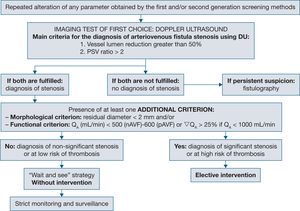

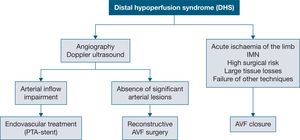

AVF creation in an upper limb determines significant changes in the limb’s haemodynamics. The direct communication created between the arterial and venous system, which avoids passing through the capillary bed, causes a shunt with a large flow rate that may compromise the vascularisation of the arterial bed distal to the access. In many cases of ischaemia, the situation is aggravated by the presence of previous arterial disease in the proximal or distal territories.