Introducción: La hepatitis C crónica en pacientes en diálisis es mayor que en la población general. El estudio SHECTS, tiene como objetivos analizar el nivel de estudio y seguimiento de los pacientes con infección crónica por el virus de la hepatitis C (VHC) en hemodiálisis y determinar su prevalencia actual. Método: Estudio de cohorte multicéntrico nacional, realizado entre septiembre de 2010 y septiembre de 2011. Se envió un cuaderno de recogida de datos a todas las unidades de hemodiálisis de España para incluir información de la unidad y de la situación nefrológica y hepatológica de sus pacientes VHC-positivos. Resultados: Participaron en el estudio 187 unidades de hemodiálisis (71 hospitalarias). La prevalencia del VHC se estimó en el 5,6 %. La causa más frecuente de enfermedad renal crónica fue la glomerular (25 %); del 72,1% de los pacientes que se había sometido a una biopsia renal, el 23,2 % presentaba una glomerulonefritis que podía estar asociada al VHC. No se siponía del genotipo en el 64 %, ecografía hepática en el 61,3 %, biopsia hepática en el 87,7 %. Un tercio era seguido por un digestólogo. El 26,6 % había recibido tratamiento antiviral, con respuesta viral sostenida en el 35,3 % y suspensión del tratamiento en el 67,4 %. Conclusión: La prevalencia del VHC en hemodiálisis en España ha disminuido notablemente en la última década hasta igualarse a la de países del entorno. Estos pacientes tienen un estudio incompleto de su hepatopatía y los tributarios de tratamiento antiviral y no tratados constituyen un número considerable, a pesar de tener cargas virales bajas y ser candidatos a trasplante renal.

Introduction: The rate of Chronic hepatitis C in dialysis patients is higher than in the general population.The SHECTS study, approved by the Spanish Society of Nephrology, has the goal of analysing the level of examination and follow-up of patients with chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infections on haemodialysis, and to determine the current prevalence of these patients. Method: A national, multi-centre, cohort study carried out between September 2010 and September 2011. We sent a data collection folder to all Spanish haemodialysis units to include information regarding each centre and the nephrological/hepatological situation of their HCV-positive patients. Results: A total of 187 haemodialysis units (71 hospital-based) participated in the study. The global prevalence of HCV was estimated at 5.6%. The most common cause of chronic kidney disease was glomerular (25%); of the 72.1% of patients who had undergone a renal biopsy, 23.2% had glomerulonephritis that could have been associated with HCV. Genotyping had not been carried out in 64%, liver ultrasound had not been applied in 61.3%, and liver biopsies were not performed in 87.7%. One-third of all patients received care from a gastroenterologist. Antiviral treatment was administered to 26.6% of patients, with a sustained viral response in 35.3% and suspension of treatment in 67.4%. Conclusion: The prevalence of HCV in patients on haemodialysis in Spain has decreased to the point of reaching similar rates to those of neighbouring countries. These patients receive incomplete analyses of liver condition, and individuals who receive antiviral treatment and untreated patients constitute a large proportion, despite having low viral loads and being candidates for kidney transplants.

INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis C (HCV) virus infections in patients with stage 5 chronic kidney disease (CKD) is higher than in the general population. In haemodialysis, a prevalence of 13% is observed with high variability (1%-70%),1 even between the haemodialysis units of a same country2: it is less than 5 % in the north of Europe; around 10% in the south of Europe and the United States; and between 10% and 50% and up to 70% in many developing countries, including some regions of Asia, Latin America and north Africa.3-5 HCV infection incidence has decreased by at least 1%-2% in developed countries.1,2,6 In Spain, the prevalence of HCV infection in haemodialysis from 1997 to 2001 was estimated at 22%.1 In kidney transplants, prevalence of the HCV infection varied between 7% and 40%, also with a wide geographic and demographic variability.1,6-8

In spite of the evidence that exists on the benefits of antiviral treatment in patients with chronic hepatitis due to HCV and CKD prior to kidney transplant, only some kidney transplant protocol require treatment against HCV and it is not usually catalogued as a transplant prerequisite, but rather a recommendation.9-11

Since there is no medical literature on the level of study and follow-up of chronic hepatitis C in patients on haemodialysis, the need to carry out a cross-sectional study to compile all related aspects, with the aim of detecting improvements in its diagnosis and treatment and assessing the possibility of carrying out a multidisciplinary management between nephrologists and hepatologists.

METHOD

A data collection folder was created with clinical, analytical and complementary test parameters related to the patients’ kidney and liver situation, to be completed from the information in the medical records of patients with chronic hepatitis C on haemodialysis. This folder was sent to all the Nephrology Services and outpatient haemodialysis units in Spain and compiled in the National Nephrology Yearbook 2010, published by Medibooks, as well as a letter presenting the study, to be completed by a representative researcher from each centre. The folders had to be returned to the postal address of the coordinating centre or the e-mail address of those coordinating the study, to include the data in a central database.

The patients had to sign their informed consent to provide their data if the health centre did not have prior authorisation for their use in scientific research.

The study was approved by the Clinical Research and Ethics Committee of the coordinating centre.

The study took place from September 2010 to September 2011.

Variables

- Centre data: centre name, number of patients in the centre, number of patients with HCV infection, representative researcher for the centre, data collection date.

- Personal details of the patient: initials, sex, age, height, weight.

Kidney situation

- Aetiology of chronic renal failure.

- Renal replacement therapy: current, duration; previous, duration; vascular access (current, duration; previous, duration). Anticoagulant therapy (yes/no): oral (yes/no), dose, cause; intradialytic (yes/no), dose.

- Candidate for kidney transplant (yes/no), active on the kidney transplant waiting list (yes/no).

Liver situation

• Liver situation.

• Viral load, genotype; drinking habit (yes/no), alcohol consumption per day (less than 40g, 40-80g, over 80g); coinfection (hepatitis B virus, human immunodeficiency virus); glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase (GOT), glutamic pyruvic transaminase (GPT), gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT), alkaline phosphatase, direct bilirubin, total bilirubin, albumin, creatinine, International Normalized Ratio (INR), prothrombin time.

• Previous treatment of the HCV infection (yes/no): monotherapy with conventional interferon, monotherapy with pegylated interferon, combined therapy (ribavirin and interferon); duration of treatment; suspension of treatment (yes/no), reason.

•Portal hypertension (yes/no): hypersplenism (yes/no), ascites (yes/no), esophageal varices (absent, small, large). Portal hypertension complications (yes/no): upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage (yes/no), spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (yes/no), hepatic encephalopathy (yes/no).

• Beta blocker treatment (yes/no).

• Hepatic Cirrhosis (sí/no).

• Candidate for liver transplant (yes/no/not assessed).

• Liver transplant waiting list (yes/no).

• Follow-up by the Gastrointestinal System Service (yes/no).

• Complementary tests: gastroscopy (yes/no), description; colonoscopy (yes/no), description; liver ultrasound (yes/no), hepatic portal vein diameter, hepatic portal vein flow, spleen diameter, ascites; haemodynamics of the liver (yes/no), hepatic venous pressure gradient; liver biopsy (yes/no), description.

Researcher evaluation of the questionnaire on the management of their patients with HCV

• Has the questionnaire helped you to assess the management of your patients with HCV? (yes/no) viral load, genotype; drinking habit (yes/no), alcohol consumption per day (less than 40g, 40-80g, over 80g); coinfection (hepatitis B virus, human immunodeficiency virus); glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase (GOT), glutamic pyruvic transaminase (GPT), gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT), alkaline phosphatase, direct bilirubin, total bilirubin, albumin, creatinine, International Normalized Ratio (INR), prothrombin time.

• Previous treatment of the HCV infection (yes/no): monotherapy with conventional interferon, monotherapy with pegylated interferon, combined therapy (ribavirin and interferon); duration of treatment; suspension of treatment (yes/no), reason.

• Portal hypertension (yes/no): hypersplenism (yes/no), ascites (yes/no), esophageal varices (absent, small, large). Portal hypertension complications (yes/no): upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage (yes/no), spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (yes/no), hepatic encephalopathy (yes/no).

• Beta blocker treatment (yes/no).

• Hepatic cirrhosis (yes/no).

• Candidate for liver transplant (yes/no/not assessed).

• Liver transplant waiting list (yes/no).

• Follow-up by the Gastrointestinal System Service (yes/no).

• Complementary tests: gastroscopy (yes/no), description; colonoscopy (yes/no), description; liver ultrasound (yes/no), hepatic portal vein diameter, hepatic portal vein flow, spleen diameter, ascites; haemodynamics of the liver (yes/no), hepatic venous pressure gradient; liver biopsy (yes/no), description.

Researcher evaluation of the questionnaire on the management of their patients with HCV

• Has the questionnaire helped you to assess the management of your patients with HCV? (Yes/no)

Statistical analysis

The data were analysed through the SPSS software version 18. The Student’s t was used for variables with normal distribution and the Mann-Whitney test if they did not match the normality principle. The relationship between the qualitative variables of two or more categories was carried out by χ2 test.

RESULTS

Participating centre data

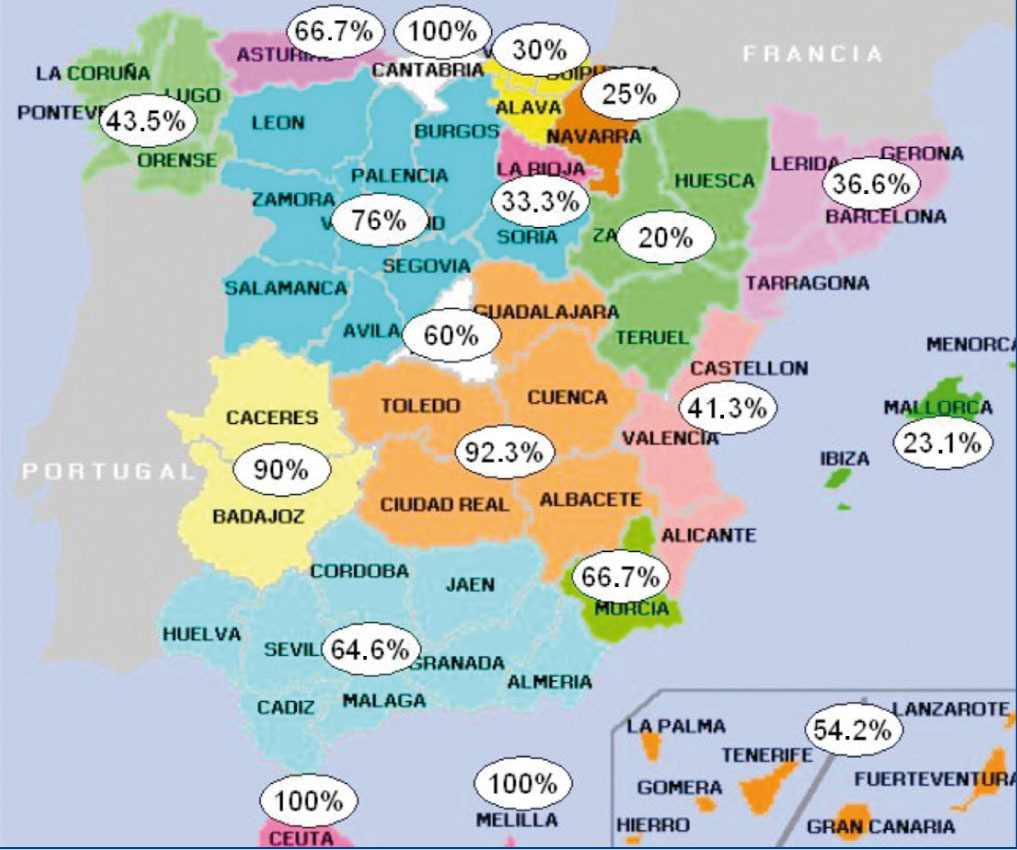

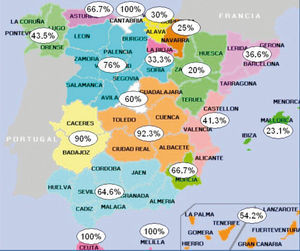

Of the 366 Spanish haemodialysis centres registered in the MediBooks National Yearbook 2010, 14 had disappeared due to transfer, merger, closure or change of name, with 352 being active: 180 inpatients and 172 outpatients. The following participated in the study: 187 centres (53,1 %): 71 inpatients (38 %) and 116 outpatients (62 %); all sent their prevalence data and 50 centres sent the complete data collection folder. The participant percentage per autonomous community is represented in Figure 1.

Of the 12 472 patients registered, 708 showed chronic hepatitis C, constituting a chronic HCV infection prevalence in haemodialysis patients in Spain of 5.6 %, from the sample surveyed. 75.9% of the centres had at least one HCV-positive patient on haemodialysis.

Personal details of the patients

Data collection folders of 232 patients (57.2 % male), with an average age of 58.8±15.1 years (range from 24 to 88 years) were received. The body mass index was 24±5.3kg/m2 (15-19.9kg/m2, 23.2%; 25-29,9kg/m2, 19%; over 30kg/m2, 28.2%).

Kidney situation

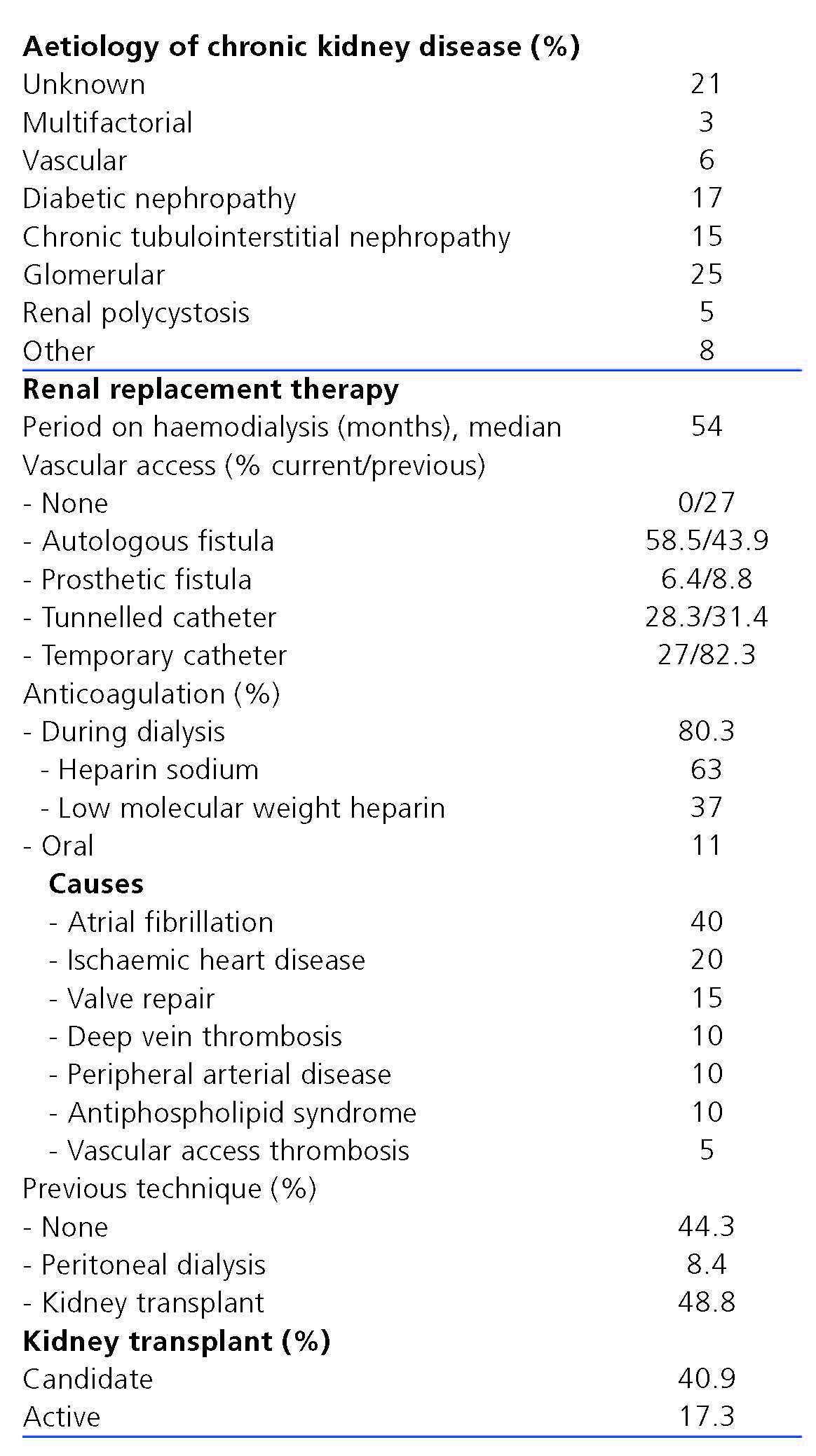

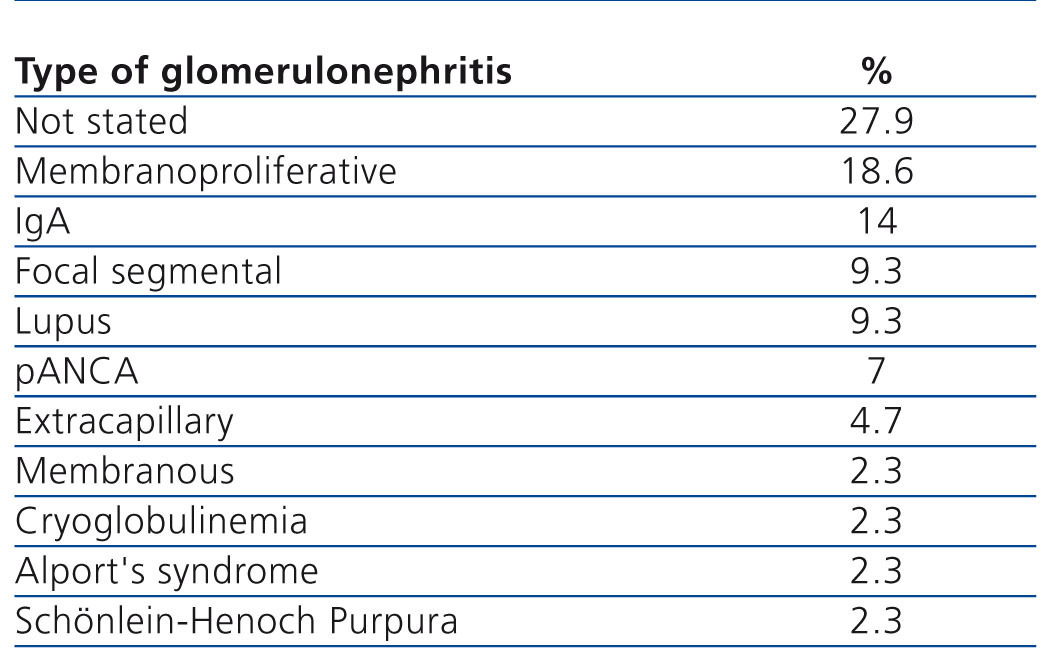

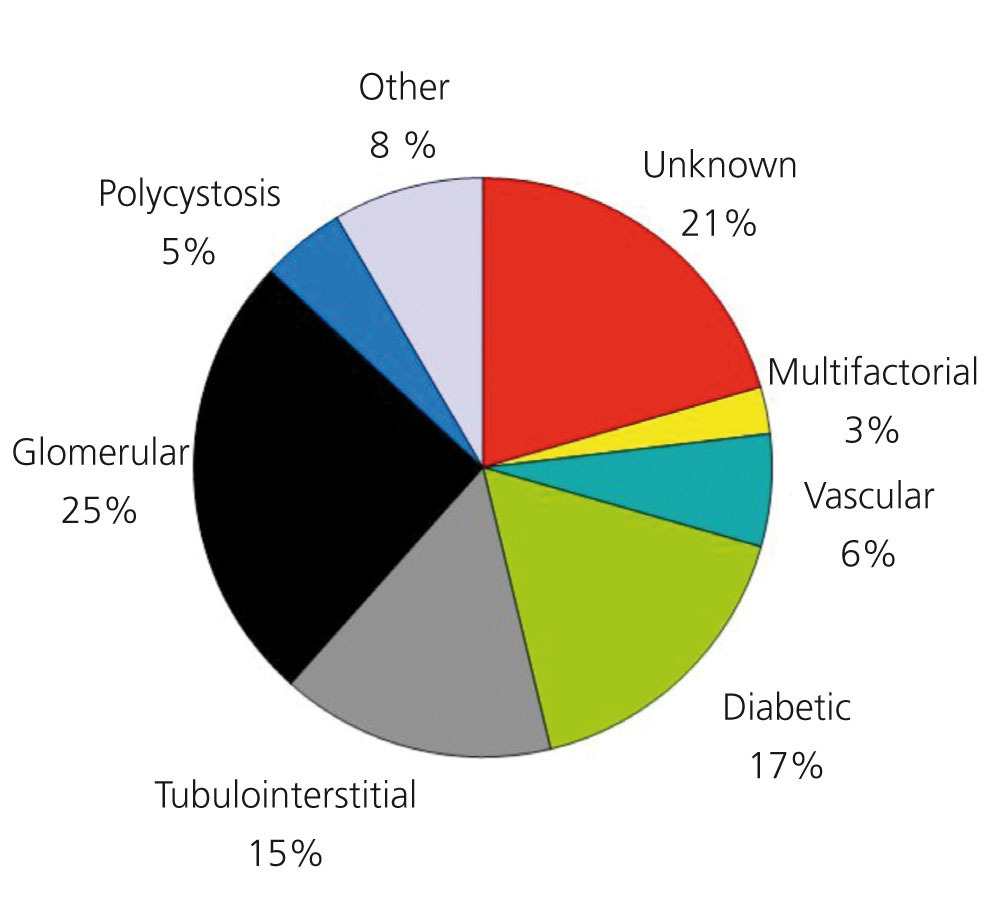

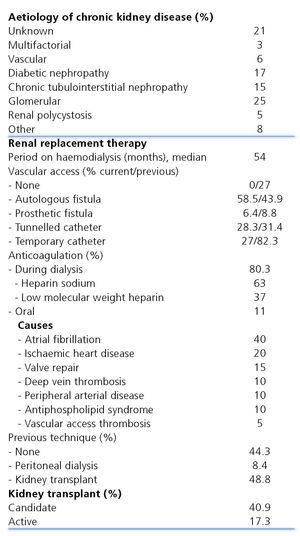

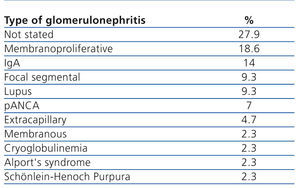

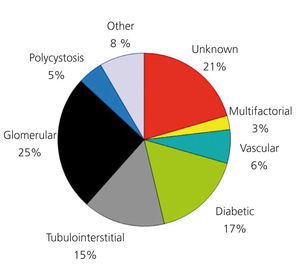

The characteristics corresponding to the patients’ kidney situation are displayed in Table 1. The most frequent cause of CKD was glomerular aetiology (25%), followed by diabetes (17%) (Figure 2). 72.1% had undergone renal biopsy, with 23.2% displaying glomerulonephritis potentially linked to HCV (Table 2).

The mean haemodialysis time was 54 months (4.5 years), with a range of one month to 32 years. 64.9% of the patients were carriers of an arteriovenous fistula; 31.4% and 82.3% had previously had at least one tunnelled catheter and one temporary catheter, respectively.

19.7 % of patients did not receive anticoagulation during dialysis; of those who did receive it, 63% did so with heparin sodium and 37%, with low molecular weight heparin. 11% underwent treatment with oral coagulants for one of the following reasons: atrial fibrillation (40%), ischaemic heart disease (20%), valve repair (15%), deep vein thrombosis (10%), peripheral arterial disease (10%), antiphospholipid syndrome (10%), vascular access thrombosis (5%).

8.4 % had previously been on peritoneal dialysis.

With respect to kidney transplantation, 48.8% of the patients had received a previous kidney transplant, 40.9% were potential candidates to renal transplantation and only 17.3% was active in the waiting list.

Liver situation

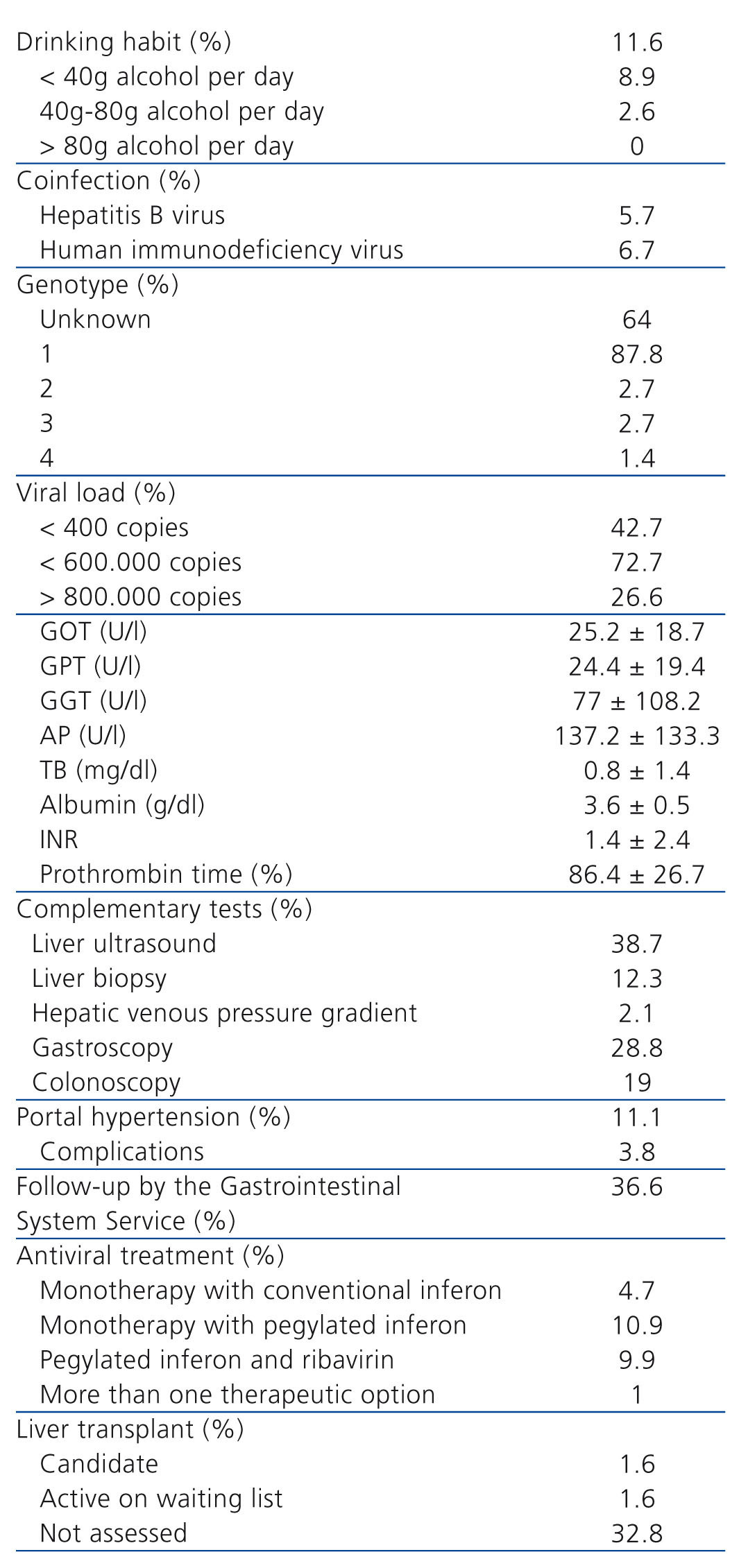

The characteristics corresponding to the liver situation of the patients is displayed in Table 3.

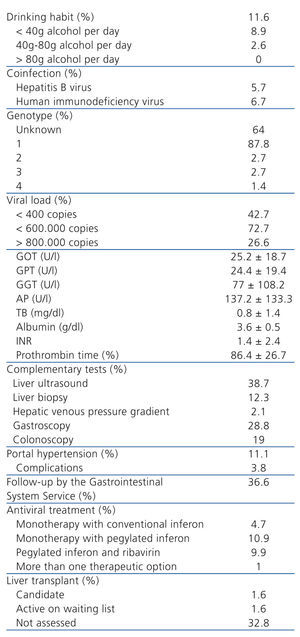

With regard to their personal background, 11.6% of patients had a drinking habit. 5.7% were co-infected by the hepatitis B virus and 6.7%, by the human immunodeficiency virus.

Of the 36% of patients whose genotype was known, 87.8% were type 1, 2.7% were type 2, 2.7% were type 3 and 1.4% were type 4. Most patients had a low viral load (less than 600,000 copies, 72.7%) or very low (less than 400 copies, 42.7%). 24.3% had elevated GPT levels (above 28U/l) and 27.2% of GGT.

The patients had undergone the following complementary tests: liver ultrasound, 38.7%; liver biopsy, 12.3%; hepatic venous pressure gradient, 2.1%, gastroscopy, 28.8%, colonoscopy, 19%. Of the 12.3% of the patients in which a liver biopsy was conducted, 23.8% had F0 histology, 23.8% F1, 28.5% F2, 4.7% F3, 4.7% F4, in 14.5% the grade of fibrosis was not determined due to insufficient sample. 42.8% of the patients with elevated transaminases received biopsies. Analytical, radiological and portal hypertension endoscopic data were found in 11.1% of patients, while 3.8% suffered complications (varicose bleeding, ascites, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis).

A third of patients (36.6%) were periodically followed-up by the Gastrointestinal System Service.

26.6% had received antiviral treatment: 4.7%, with conventional interferon, 10.9% with pegylated interferon, 9.9% with pegylated interferon and ribavirin, 1% had received at least two different treatments. In 35.3% of the patients treated a sustained viral response was obtained. 28% of the patients with hypertransaminasaemia, 36.1% of the patients with glomerulonephritis linked to HCV and 51.4% of the patients followed up by the Gastrointestinal System Service received antiviral treatment. Of 51.4% of the active patients in the waiting list for kidney transplant who received treatment, 44.4% obtained a sustained viral response. The treatment had a mean duration of 7.4±5 months; 67.4% had suspended treatment: 35% due to lack of response, 31% due to anaemia, 21% due to intolerance, 3% due to secondary psychosis, and 10% for other reasons.

The same patients who were candidates for liver transplant were on the waiting list (1.6%); 32.8% had not been assessed for liver transplant.

Evaluation of the questionnaire

83.8% of researchers gave a positive assessment of the influence that the questionnaire had in their self-evaluation on the management that they carried out on their HCV-positive patients.

DISCUSSION

This study situates the prevalence of chronic hepatitis C in haemodialysis in Spain at 5.6%, similar to that of its neighbouring European countries. The reduction in the prevalence of HCV in haemodialysis in Spain since 2001 may be due to various reasons. It is possible that the death of some infected patients may have been caused by contaminated transfusions before the 1990’s. In addition, the preventive measures carried out by the Spanish Nephrology Society may have contributed to decreasing contagion, since most centres throughout the decade from 2000 to 2010 have adopted some isolation measures.12 The prevalence study carried out from 1997 to 2001 included around twenty centres, which also may have caused a bias towards that sample. In spite of the attempts to concentrate HCV-positive patients in specific units, 75.9% of haemodialysis centres in Spain have at least one patient with chronic hepatitis C, and as such, sources of infection continue to exist which oblige efforts to be made regarding prophylaxis measures, more than on the distribution of patients.

Unlike HCV-negative patients, who display high blood pressure and diabetes as causes of their CKD, patients with chronic hepatitis C more commonly have a glomerulonephritis aetiology in 23.2% with a potential link to HCV (membranous or membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis with or without cryoglobulinemia). The haemodialysis period is long (a median of 54 months), with a very wide range (one month to 32 years), which helps to understand the higher likelihood of infection since there is longer exposure, as well as a better indication of anti-viral treatment because of a longer life expectancy. The high percentage of patients not requiring anticoagulation during analysis without being anticoagulated (19.7%) must be highlighted, which would exclude different coagulopathies, amongst them, that secondary to portal hypertension. Although the number of candidates for kidney transplant is high, less than half are included on the waiting list. As with HCV-negative patients, the use of temporary and tunnelled catheters is high and in many cases occurs in subjects selected for arteriovenous fistula, which they currently bear (58.5 % autologous, 6.4 % prosthetic).

HCV-positive patients display factors forecasting good response to antiviral treatment, such as low viral load (72.7%) and the degree of fibrosis (76.1% of patients had a degree of fibrosis under or equal to F2). Nevertheless, it is striking that only 26.6% had received antiviral treatment. Furthermore, only 28.8% of those displaying hypertransaminasemia had been treated, which, in the past, was associated with high necroinflammatory activity in these patients, although CKD in haemodialysis produces hypertransaminasemia and the values may be underestimated.13 36.3% of those who may have had secondary glomerulonephritis had received antiviral treatment, 51.4% of those who were being followed up by the Gastrointestinal System Service and 51.4% of those who were in the kidney transplant waiting list, with a high percentage of treatment suspension (67.4%) and, nevertheless, with an acceptable sustained viral response rate (44.4%). Likewise, Gastrointestinal System Service follow-up is low (36.6%), bearing in mind that the HCV infection may develop into cirrhosis and result in hepatocellular carcinoma. It is striking that 73.6% of patients had an ultrasound, but only 38% with description of liver morphology and dynamic.

The high assessment of nephrologists about the usefulness of the questionnaire (83.3%) leads to strategies of this type being considered with the aim of carrying out an evaluation of the management of patients and treatment attitudes.

This study is the first on a worldwide scale that assesses the level of study and follow-up of HCV-positive patients in renal replacement therapy with haemodialysis. It highlights the scarcity of the study of patients with liver disease due to HCV in haemodialysis and, as a result, their insufficient follow-up. It also demonstrates that there is a considerable group of infected patients who qualify for antiviral treatment, which would avoid complications secondary to liver disease, would decrease post-transplant kidney complications and would reduce the risk of HCV contagion in a Haemodialysis Unit.

It would be necessary to establish joint management protocols for patients with chronic HCV infection on haemodialysis, with the participation both of nephrologists and of hepatologists.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest related to the contents of this article.

Redundant publication

The results presented in this study have not been sent to be published or been published before in their entirety or in a large part, except as a poster, summary, scientific meeting presentation or register of clinical trials, in which case the reference is given: García Agudo R, Aoufi Rabih S, Barril Cuadrado G. The importance of the study of liver disease due to HCV in patients on haemodialysis. XLI National Congress of the Spanish Nephrology Society, 2011.

APPENDIX. Collaborating researchers in the SHECTS multi-centre Spanish study

Table 1. Kidney situation of HCV-positive patients on haemodialysis

Table 2. Glomerulonephritis types

Table 3. Liver situation of HCV-positive patients on haemodialysis

Figure 1. Map of Spain with the participation of haemodialysis centres by autonomous community

Figure 2. Aetiology of chronic kidney disease