Background: Advanced chronic kidney disease (ACKD) has a great impact on health-related quality of life (HRQL). The use of this variable in studies in our field is becoming more frequent, although there has been no comprehensive review of how Spaniards with ACKD are assessed. Aims: To offer a contrasted vision of the HRQL assessment tools that are most often used on Spanish ACKD population, also analysing how this population perceive their quality of life. Method: A review was carried out on literature published on studies undertaken in Spain that had used some kind of instrument, either generic or specific, in order to measure HRQL in patients with different stages of ACKD. Studies in kidney transplant patients were excluded when they were independently reviewed. The research was carried out in CINAHL, CUIDEN, DOCUMED, EMBASE, ERIC (USDE), IME, LILACS, MEDLINE, Nursin@ovid, PubMed, Scielo, Web of Science and TESEO. Results: 53 articles published between 1995 and May 2014 have been included in this review. Renal replacement therapy is the variable that is most often associated with the study of HRQL, with haemodialysis being the most studied. Most of the studies found are cross-sectional and the Short Form-36 Health Survey is the most used instrument. Conclusions: The majority of the studies show how HRQL is significantly affected in patients who receive renal replacement therapy. These results are independent from the instrument used to measure health-related quality of life and other associated variables throughout the various studies. HRQL has been particularly analysed in patients on haemodialysis, using mainly observational methods and the Short Form-36 Health Survey. There is a need for more studies that address aspects such as HRQL in the pre-dialysis phase, as well as studies with larger samples and longitudinal, analytical and experimental designs.

Antecedentes: La enfermedad renal crónica avanzada (ERCA) tiene un gran impacto sobre la calidad de vida relacionada con la salud (CVRS). Cada vez es más frecuente el uso de esta variable en estudios en nuestro medio, aunque no se dispone de una revisión global sobre cómo se ha estudiado en población con ERCA española. Objetivos: Ofrecer una visión contrastada de los instrumentos de evaluación de la CVRS más usados en la población española con ERCA, analizando además la calidad de vida percibida por esta población. Métodos: Se llevó a cabo una revisión de la literatura publicada sobre estudios realizados en España que hubieran empleado algún instrumento para medir la CVRS, genérico o específico, en pacientes con diferentes estadios de ERCA. Se excluyeron estudios en pacientes trasplantados renales cuando eran estudiados de forma independiente. La búsqueda se realizó en CINAHL, CUIDEN, DOCUMED, EMBASE, ERIC (USDE), IME, LILACS, MEDLINE, Nursin@ovid, PubMed, Scielo, Web of Science y TESEO. Resultados: Se han incluido en esta revisión 53 artículos publicados entre el año 1995 y el mes de mayo de 2014. La terapia sustitutiva renal es la variable con mayor frecuencia asociada al estudio de la CVRS, siendo la hemodiálisis la más estudiada. La mayoría de los estudios encontrados son transversales y el Short Form-36 Health Survey es el instrumento más usado. Conclusiones: La mayoría de los estudios muestra cómo la CVRS se ve afectada de forma importante en pacientes que reciben terapia sustitutiva renal. Estos resultados se muestran independientes del instrumento usado para medir la calidad de vida relacionada con la salud y de otras variables asociadas a lo largo de los distintos estudios. La CVRS ha sido analizada especialmente en pacientes en hemodiálisis, con diseños fundamentalmente observacionales y con el Short Form-36 Health Survey. Se necesitan más estudios que aborden aspectos como la CVRS en la etapa prediálisis, así como estudios con muestras más grandes y diseños longitudinales, analíticos o experimentales.

INTRODUCTION

Advanced chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a condition which by its nature has a great impact on health related quality of life (HRQL). From the initial stages of the disease to its end stage, symptoms, restrictions (especially dietary) and its treatment affect the daily life of these patients.

The guidelines Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (K/DOQI)1 on chronic kidney disease state that in the course of this disease patient HRQL deteriorates, and that this is related to demographic factors (age, sex, education level, economic situation, etc.), with the complications of CKD (anaemia, malnutrition, etc.), with diseases that cause this disease (hypertension, diabetes, etc.) or with impaired renal function itself. Based on this, they advise that in all patients with a glomerular filtration rate below 60ml/min (stage III), HRQL is evaluated regularly in order to establish baseline function and monitor changes occurring over time as well as to evaluate the effects of various interventions on HRQL1. Baseline HRQL is of great importance to assess the results of interventions made during outpatient follow-up by doctors and nurses.

In 1994 the World Health Organization Quality of Life Group (WHOQOL)2, was created, which defined quality of life as "an individual's perception of their position in life in the context of culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards and concerns."

It is difficult to find a consensus when defining HRQL. A currently accepted concept focuses on the subjective assessment by the person of how healthcare and health promotion influence their health status and their ability to achieve a performance level that allows them to continue performing those activities that are important to them and affect their welfare. Therefore, HRQL is a multidimensional concept based on the patient’s subjective perception3, in which "non-clinical" factors such as family, friends, religious beliefs, work, income and other life circumstances are also involved4.

HRQL is a concept constructed from many facets of life and patient situations, which are grouped around several dimensions: physical functioning, psychological wellbeing, emotional state, pain, social functioning, general perception of health and other factors, among which are included sexual function, life satisfaction, impact on labour productivity and activities of daily living. The number of visits to a doctor due to illness or medical problems and the need for drugs5 are also frequently used as indicators of HRQL.

In 19956 the WHOLQOL group agreed on the following attributes of HRQL: subjective, multidimensional, including positive and negative feelings, and that it is variable over time.

Interest in the concept of HRQL began in the early seventies and has increased over the last twenty years, becoming a central goal of health care and an essential measurement performed by so called patient-reported outcome (PRO) instruments. PRO instruments are self-reports of Health-related quality of life by patients without mediation on the part of any professional7 to capture concepts related to their experiences, how they feel or function in relation to their illness or treatment8, and go beyond the classical evaluation of survival, traditional clinical efficacy or adverse events. The increasing use of PRO instruments in experimental studies is particularly marked in clinical drug trials, among which HRQL is the most used.

Given its ability to focus on the real needs perceived by the population, HRQL determination is considered a highly valuable discriminating tool for planning health policies or resource9 distribution.

The importance of including HRQL indicators in the clinical management of patients with CKD stems from the close relationship between HRQL, morbidity and mortality, as many common factors10,11 appear when analysing these three parameters. Therefore, in order to maintain an optimal HRQL in patients undergoing renal replacement therapy (RRT) is a key element that should guide decision-making in CKD treatment programmes.

Numerous published instruments are available to measure HRQL. Most are composed of a series of items or grouped questions in different dimensions that measure various aspects of health. Questionnaires measuring HRQL must meet the same criteria of validity, reliability and sensitivity, as required of any other measurement of health, and have a properly translated Spanish version validated for use in Spanish patients.

Before deciding on the choice of instrument for measuring HRQL, it is important to know how to use it correctly, apply scoring and carry out an analysis. For some instruments there are very useful reference population rules for comparison with a specific population. The choice of instrument depends on the intended purpose (monitoring the course of health care is different to assessing the impact of a clinical trial), the type of patients that provide data (with greater or less discriminatory power) and the mode of administration of the questionnaires. Most authors suggest the desirability of using different HRQL measurements to extend the range of the results obtained. The synergies or differences found among the results obtained should be explained in relation to the questionnaire used12.

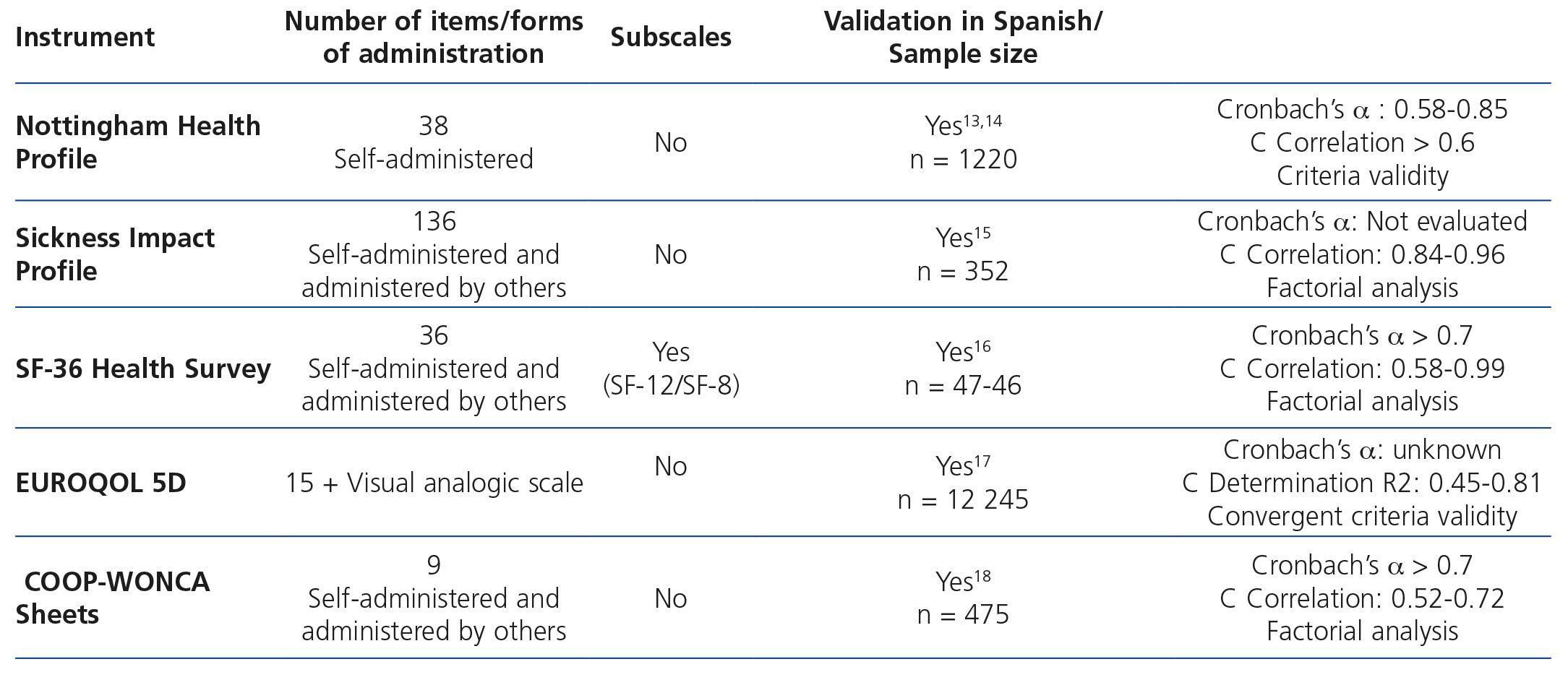

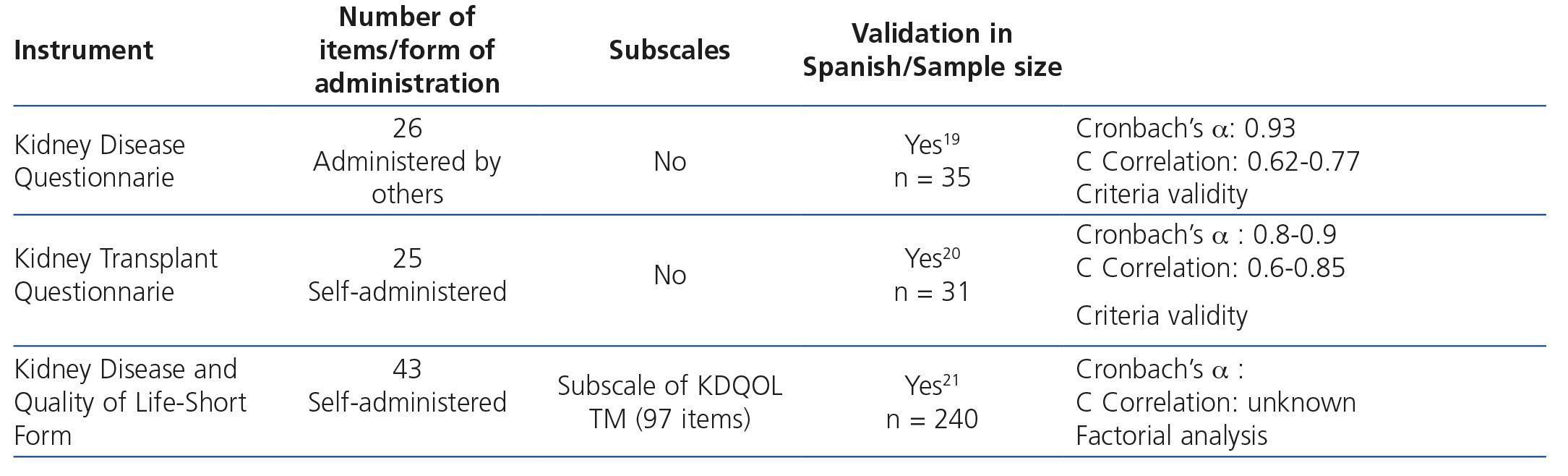

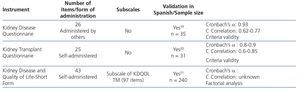

There are generic versions of instruments to measure HRQL in Spanish (Table 1) that can be used in patients with CKD and others that are specific to renal disease12 (Table 2).

The Short Form-36 Health Survey (SF-36) is the most widely used in the national and international literature to measure HRQL. Despite being a generic questionnaire and the existence of specific questionnaires for these patients, it is also the most widely used to measure HRQL in patients with CKD. In our country many studies use it for measuring HRQL in relation to RRT techniques, sociodemographic variables anxiety, depression, coping strategies, etc. (Table 3).

If we compare, for example, studies examining HRQL in relation to the CKD and RRT based on the questionnaire used, we find that all show a poorer quality of life in these patients either using the specific questionnaire for renal disease Kidney Disease and Renal Patients Quality of Life-Short Form (SF-KDQOL)75,76 or generic SF-3677-80 and EUROQOL 5D (EQ-5D)81.

In the literature there are two recent meta-analysis that include articles analysing quality of life in patients receiving RRT versus transplant patients, one including articles in which SF-36 questionnaire was used and one in which SF-36 and EQ-5D were used, both reviews reached the same conclusion: HRQL in patients who have received a kidney transplant is better than in those receiving RRT regardless of the questionnaire used82,83.

HRQL measurement is common in patients with CKD, performed by both medical and nursing staff, since it makes it possible to evaluate patients continuously during prior follow-up before beginning RRT, helping to provide individualised care for each person according to their personal characteristics and life situations.

Furthermore, to assess HRQL it is important to adjust to cultural and population conditions defining this construct in each country and to specific situations, this applies to both the quality of the translations of the questionnaires as to the use of appropriate reference values.

HRQL is increasingly being used in more studies in our country, but there is no review available so far to evaluate articles published on the Spanish population. The purpose of this review is to provide a contrasted view of the instruments most commonly used in our environment when measuring HRQL in patients with CKD, assessing results according to the instrument used.

METHOD

A review was performed of the published literature on studies conducted in Spain that had used an instrument for measuring HRQL, validated in Spanish, whether generic or specific. Inclusion criteria were as follows: studies conducted on adult Spanish population, including different stages of CKD (pre-dialysis stage and dialysis, accepting studies of transplant patients when compared with patients in pre-dialysis or dialysis) with a sample size of at least ten patients per study group. All studies included in this review have used instruments that have been validated in Spanish, as shown in Table 1 and Table 2.

The search was conducted in the following databases: CINAHL, CUIDEN, DOCUMED, EMBASE, ERIC (USDE), IME, LILACS, MEDLINE, Nursin@ovid, PubMed, Scielo, Web of Science, Web of Knowledge and TESEO data base of PhD thesis. The words used during the search were “quality of life”, “health-related quality of life”, “chronic renal failure”, “chronic kidney disease”, “haemodialysis”, “peritoneal dialysis”, «predialysis», dial*, haemodial*.

Strategies of previous searches were supplemented by manual review of bibliographies of identified articles and review articles.

In the case of papers from the same research team, same school or same sample, after checking that it was the same study, we included those containing a larger sample and most recent studies, rejecting others.

The search began in October 2012 and ended in May 2014, and all articles published both in Spanish and in other languages between 1995 and May 2014 that were carried out on Spanish populations were included.

RESULTS

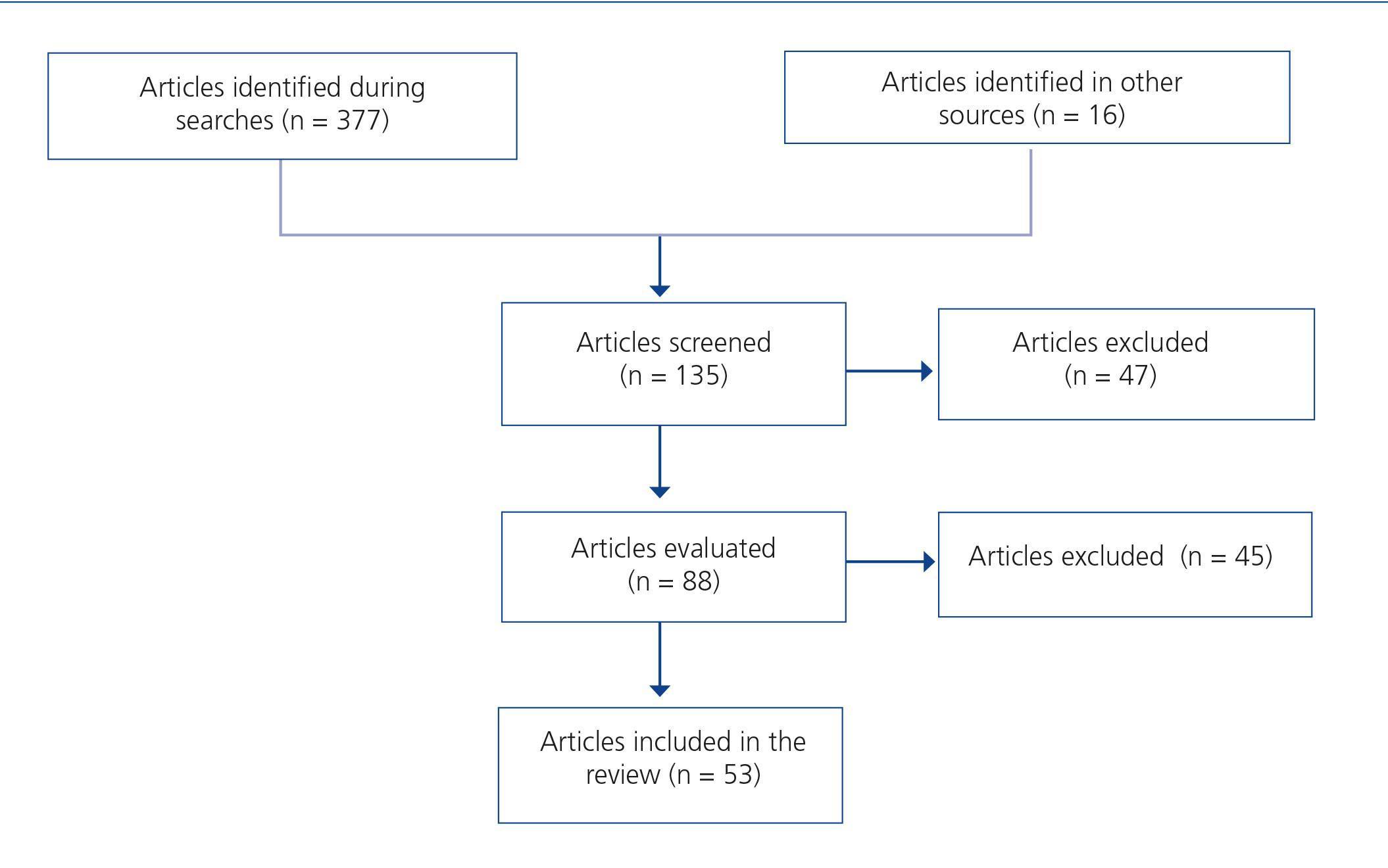

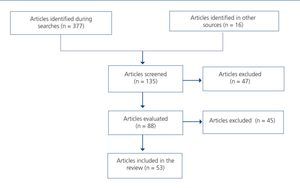

A total of 377 articles were found. The title and abstract of 135 of them were reviewed and finally the full text of 88 was evaluated. The full selection process is detailed in Figure 1.

Of the articles found, 53 met the criteria for inclusion in this review. Publication dates were from 1995 to May 2014. One of the studies was a doctoral thesis.

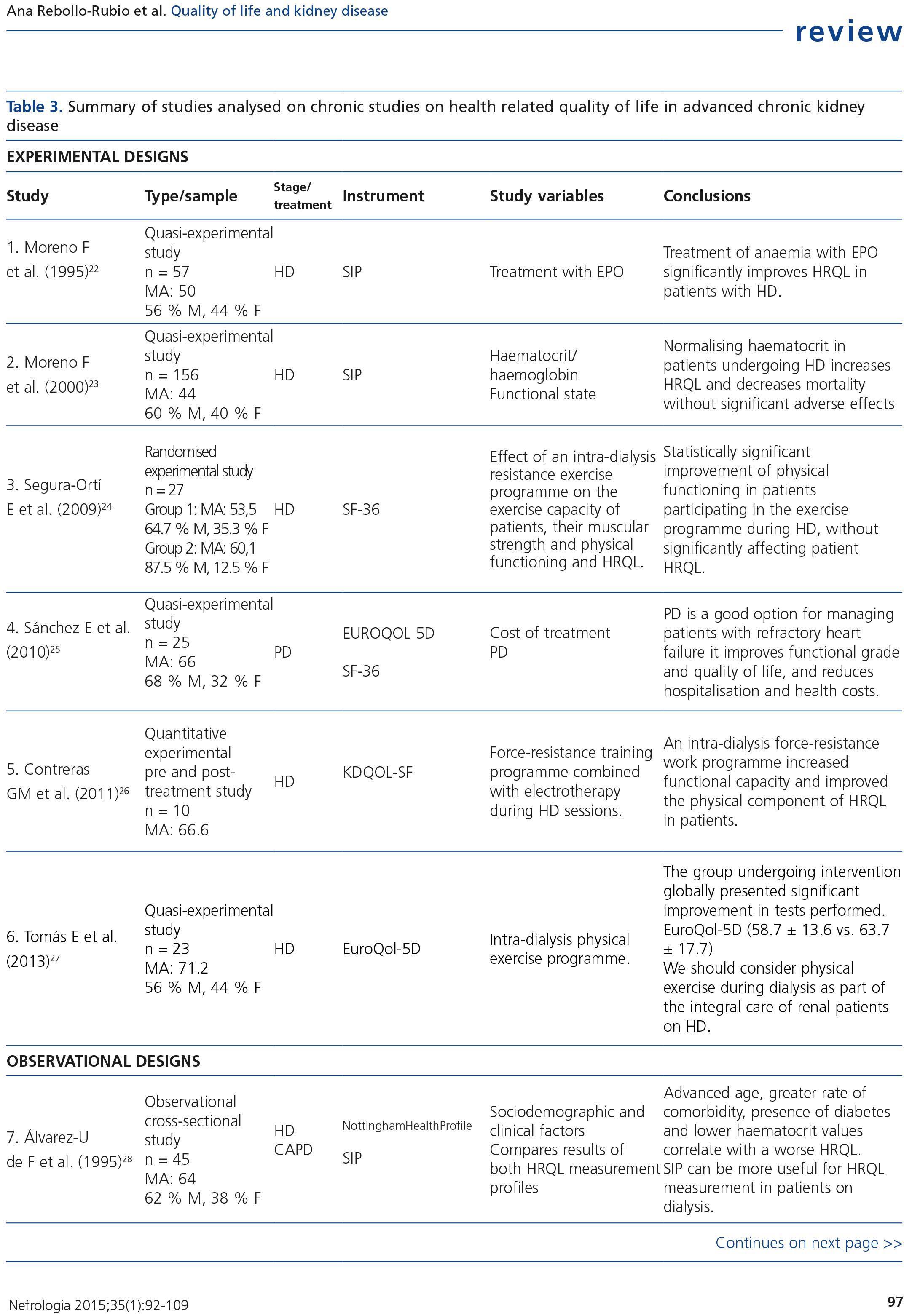

Table 3 summarises the characteristics of the studies analysed.

Types of patients in which health related quality of life was studied

In general, when studying HRQL in renal disease, it is on patients on haemodialysis (HD) where we find the greatest number of studies, either alone or in combination with other stages/treatments. Consequently, in 49 of the articles found (92.45%) HRQL is analysed in patients on HD, compared with 26.41% (n = 14) in patients undergoing peritoneal dialysis (PD) and 5.66% (n = 3) in patients in the pre-dialysis stage, this group is the least studied over the last twenty years. It must be noted that HRQL in patients receiving PD without being compared to other stages or treatments is only studied in three articles, the first from 2008, with no studies until that moment focusing exclusively on this type of RRT. PD appears in eleven more articles compared to other stages/treatments.

The number of patients included in the articles varies considerably, as we established a minimum of ten to be included in this review. The average sample size is 143.32 (SD 180.170) patients, although there is great variability in these figures, from a maximum of 1013 patients to a minimum of 10 patients, with a median of 75 years of age.

HRQL results obtained were independent of the type of instrument used. We found that patients who had received a renal transplant had a better HRQL than those on RRT (HD/PD).

Types of instruments used to assess health related quality of life

Of the studies reviewed, only eleven (20.75%) use two instruments together to measure HRQL, the remainder used only one.

The instrument mainly chosen (52.83%, n =28) by the authors in our country to measure HRQL is SF-36 (generic instrument). This instrument is followed by KDQOL-SF, used in 13.2% (n = 7) of cases, also the Sickness Impact Profile, with 13.2% (n = 7), and COOP-WONCA Charts, with 13.2% (n = 7). Fewer studies used the Nottingham Health Profile, with 11.32% (n = 6) and the Kidney Disease questionnaire was only used in a study of Spanish population (1.88%).

Types of studies most often used to measure health-related quality of life

Most of the studies included in this review are observational and cross sectional: 84.9 % (n = 45). 7.5% (n = 4) are quasi-experimental studies, 3.8% (n = 2) experimental, as also longitudinal observational studies: 3.8% (n = 2).

Impact and evolution of health-related quality of life in different studies

Since the first HRQL studies in our country to this day, RRT itself, either HD or PD, is the variable most commonly associated with HRQL studies in patients with CKD.

Most of the studies show how HRQL is significantly affected in patients receiving RRT. These results are independent of the instrument used to measure HRQL and other associated variables.

Many studies in this review show association between the presence of anxiety and depressive symptoms and the perception of a poorer HRQL. Anxiety and depression are present in varying degrees in all people with CKD, in which the presence of any of these symptoms is analysed in relation to perceived HRQL31,38,40,41,43,44,46,50,55, 56,58,59,65,69,71,73.

Comorbidity associated with CKD also appears in the studies analysed as a highly influential variable on HRQL28,29,32,33,42,47,56,57.

In reviewing the association between patient age and perceived HRQL, there are differences in the results obtained, with studies in which there is a positive association between age and HRQL33,35,36,39, and others in which there is a negative association, although we must say that comorbidity appears as an age and HRQL28,29,42,56,57 related variable.

Only three studies31,61,65 compare HRQL (SF-36) according to whether the patient is receiving HD or PD, and found no significant differences in HRQL according to type of treatment chosen in our country. Furthermore, Ruiz de Alegría et al. (2008) note that continuous outpatient PD patients have a higher life satisfaction and cope better with life than those on HD (n = 93).

In over 77% of the articles included in this review, the male population is larger than the female. 100% of the studies using sex as a study variable showed a poorer HRQL perceived by women, compared with men. So far it has not been determined whether this is because there is a greater impact of the disease and its treatment on them or if, on the other hand, this reflects sex differences that also occur in the general population. A study was performed in Spain, using the SF-3684 questionnaire, on 9151 subjects where the effect of sex on HRQL in the general population is clear.

DISCUSSION

From the early stages of kidney disease, the symptoms that accompany it are reflected in patients’ daily life. RRT only partially corrects uraemic symptoms, but creates substantial changes in the daily life of these patients, caused by having to go to hospital three times a week in the case of HD, daily peritoneal fluid refills in the case of PD, major dietary restrictions in all cases, etc. All these circumstances significantly decrease quality of life in patients in the last stages of CKD.

HD is still the most used RRT technique in Spain. Consequently, for example, we found that in Andalusia in 2013 it was the method of choice for new incidents in 81.4% of cases, followed by the PD in 15% and advance renal transplantation in 3.6%85. Therefore, it is not surprising, given the high number of patients who choose this form of treatment, that most of the studies on CKD Spanish populations in which HRQL is measured have focused on HD.

The stage prior to the start of the RRT is little studied, despite its importance and the high number of patients currently attending medical and nursing consultations during this period. There are also few studies on PD, a treatment that is increasing, which more people are choosing in Spain, as also more extensive studies with a higher number of patients comparing the difference in perceived quality of life among Spanish PD and HD populations.

We did not find significant differences when analysing HRQL in different RRT treatments in Spain. This finding is partly consistent with the overall results seen in the literature, although there are a few more physical components of HRQL in patients undergoing HD86. The few studies carried out in Spain make it impossible to study this issue in greater depth and this is an area that urgently requires further investigation.

SF-36, despite being a generic questionnaire, is most often used when assessing HRQL in patients with renal disease, both in our country and internationally82. So far there are no studies using its reduced form (SF-12).

The number of patients included in these studies is often low, with the consequent losses in possibilities of generalisation and statistical power, demonstrating a clear need for new multicentre studies with larger and more diverse samples, in order to better assess the external validity of results and also include patients in pre-dialysis.

The small number of studies with strong designs (longitudinal, analytical, experimental) is remarkable, although there are published clinical practice guidelines1,87 on the usefulness of HRQL evaluation in cohorts of patients in pre-dialysis or RRT to assess the impact of disease or treatment over time.

The patient’s psycho-emotional state is another aspect that should be taken into account when assessing a person with CKD. Because HRQL is a multidimensional concept, in which the psychological state of the individual plays an important role, problems such as depression or anxiety have a big impact on HRQL. It was found that the psychosocial constructs that are more closely associated with HRQL are stress, affection and cognitive evaluation88. Therefore, it is very important to identify these states of anxiety and depression in patients with CKD to make it possible to treat them appropriately and systematically and thorough evaluation of the psycho-emotional state is recommended as an integral part of the treatment offered to optimise quality of life89. Studies would be necessary to assess HRQL in the presence of affective disorders such as anxiety or depression.

The results of this review show CKD has a significant impact on patient’s quality of life.

We conclude that measurement of HRQL should be part of professionals’ routine and systematic practice when treating renal patients. This measurement can provide very valuable and important information, allowing us to act on the most affected dimensions, thus achieving the best possible state of well-being for these patients.

Acknowledgements

To our colleagues Magdalena and Rocio Tapia, for their invaluable help.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest related to the contents of this article.

Table 1. Generic instruments used for assessing health related quality of life in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease in Spain

Table 2. Specific instruments used for evaluating health related quality of life in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease in Spain

Table 3. Summary of studies analysed on chronic studies on health related quality of life in advanced chronic kidney disease

Figure 1. Process of articles selections