Cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection has a major impact on morbidity and mortality after transplantation. Measures aiming prevention, diagnosis and treatment can improve outcomes in patients with kidney transplant.1

We present the case of a 59-year-old male with chronic kidney disease of unknown aetiology, he was kidney recipient of a deceased donor in June 2019; he received induction therapy with basiliximab and immunosuppression with tacrolimus (TAC), mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) and prednisone (PRD), and since he was when D+/R− he received prophylaxis with oral valganciclovir (VGCV) for three months, Septrin Forte and itraconazole. The patient was discharged with a serum creatinine of 2.8 mg/dl.

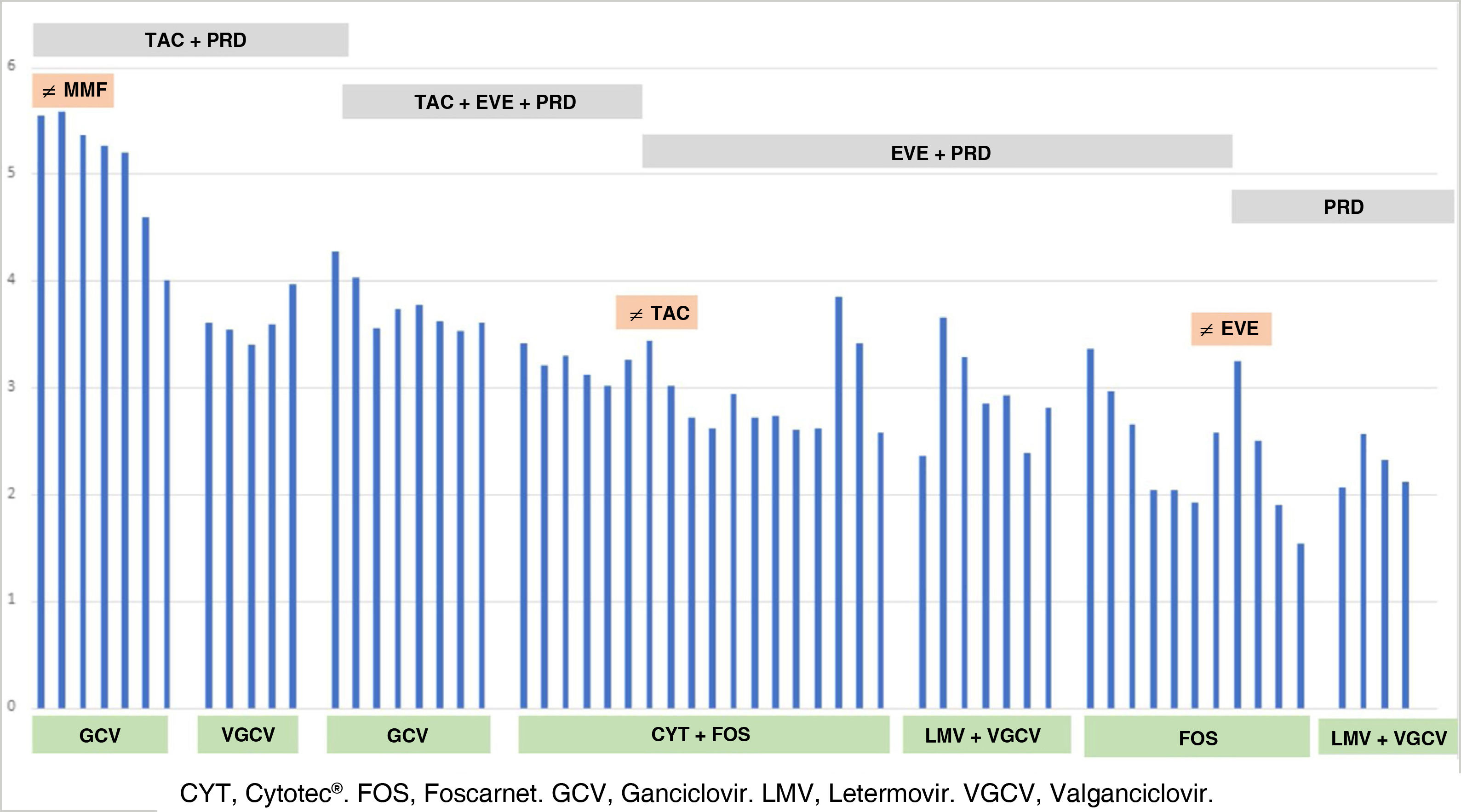

He was admitted after fourth months, one month after completing VGCV, for viral syndrome and a PCR for CMV of 350,000 IU/ml. MMF was discontinued, and he remained on TAC and PRD, and he was started with intravenous ganciclovir (GCV) adjusted to renal function. After clinical improvement and PCR of CMV IU/ml, the patient was discharged with creatinine 2.1 mg/dl and treatment with VGCV.

Two months later, he was admitted for fever, asthenia, diarrhoea and persistent viral replication. GCV was started at a dose of 10 mg/kg/day with no viral response. There was GCV resistance due to A594V mutation, UL97 gene. The patient’s fever and diarrhoea persisted, and a colonoscopy showed CMV gastrointestinal disease. GCV was discontinued, Foscarnet® (FOS) (3000 mg/12 h) was started in combination with anti-CMV immunoglobulins (Cytotec®) (70 ml/48 h), replacing TAC by everolimus (EVE). During admission, the patient presented with hypocalcaemia, hypomagnesaemia and polyuria, requiring intravenous replacement. After clinical improvement and a decrease in viral replication associated to the administration of FOS, the patient developed central venous catheter-related septic shock requiring admission to the ICU. FOS was discontinued and one week later, after a new CMV rebound (7000 IU/ml), it was restarted with letermovir (LMV) 800 mg daily. He was discharged with LMV and VGCV with a viral load of 231 IU/ml and immunosuppression with EVE and PRD.

One month after discharge, he had a new episode of anaemia, leukopenia, thrombocytopenia and CMV rebound (2290 IU/ml). FOS and non-specific immunoglobulin 500 mg/kg/day were started due to parvovirus co-infection (1,000,000 IU/ml). Despite responding well initially, an increase in CMV PCR was observed and EVE was suspended, maintaining immunosuppression with PRD only. The patient then progressed favourably and he was discharged from hospital again with LMV 400 mg/day and VGCV 450 mg/day, with CMV 116 IU/ml.

After three months, antiviral treatment was stopped due to the absence of viral replication. At six months follow-up, creatinine was 2 mg/dl and proteinuria 0.3 mg/dl, with no evidence of CMV, BK, Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) or parvovirus replication.

Fig. 1 shows the evolution of CMV replication, antiviral treatment and immunosuppression.

Following clinical practice guidelines,2 our patient was treated three months with VGCV as prophylaxis; with GCV for late disease, and maintained up to three weeks with VGCV after achieving viral load suppression.

Resistance to antiviral drugs is suspected and a genetic study should be requested if viral load or clinical symptoms persist or increase despite appropriate treatment.2 Our patient had a mutation in viral phosphotransferase (A594V, UL97 gene). Mutations in UL97 are the most common mutations leading to GCV resistance, of which UL97 A594V is the most frequent, resulting increasing GCV resistance by 8.3-fold.3 GCV and VGCV require UL97-mediated phosphorylation to block human CMV DNA replication, while FOS acts independently.4 In the event of GCV resistance, the use of FOS is recommended.1,2

The most significant adverse effect of FOS is nephrotoxicity, characterised by deposition of calcium crystals in glomerular capillaries,5 which can be prevented by adequate hydration. The use of FOS in patients with kidney dysfunction should be evaluated due to problems associated with overdose.6

Given the severity of the disease, we administered anti-CMV immunoglobulins (CMVIG) in combination with FOS although its role is not well defined.1,2 Schulz et al.7 conclude that, although the decision on the use of CMVIG is based on clinical experience, it seems reasonable to consider it in cases of CMV resistant to GCV or in severe and complicated cases.

Other alternatives for managing GCV-resistant CMV have been reported.2 LMV is an antiviral that inhibits the viral terminase complex and has been approved for CMV prophylaxis in haematopoietic cell transplantation,8 although its efficacy in other organs is unknown. Turner et al.9 and Phoompoung et al.10 agree that the use of LMV improves clinical symptoms, without adverse effects, although virological suppression is not always achieved.

Given the refractory nature of treatment in our patient, we decided to suspend EVE, keeping him immunosuppressed with corticosteroids alone, and continuing with LMV 400 mg/day and VGCV 450 mg/day, thereby achieving a sustained viral response.

We conclude that LMV could be a therapeutic alternative in cases of resistant CMV disease. Further studies are required to support its use.