Breakage of peritoneal catheters is an emergency of the technique that is uncommon but which requires immediate action when there is leakage of the dialysate and risk of infection. Early and adequate intervention can save broken catheters without interrupting peritoneal dialysis. We report our experience repairing damaged catheters using the Quinton® Peri-Patch repair kit (Quinton Instrument Co., Tyco Healthcare Group LP. Mansfield, MA., U.S.A.).

La rotura del catéter peritoneal es una emergencia de la técnica, infrecuente, pero que obliga a una actuación inmediata ante la fuga del dializado y el riesgo de infección. Una intervención temprana y adecuada puede salvar los catéteres rotos sin interrumpir la diálisis peritoneal. Presentamos nuestra experiencia reparando catéteres dañados utilizando el kit de reparación de Peri-Path de Quinton® (Quinton Instrument Co., Tyco Healthcare Group LP. Mansfield, MA., U.S.A.).

INTRODUCTION

Mechanical complications are a common cause of removal of peritoneal catheters and even change of type of haemodialysis. Among these, breakage or damage of the peritoneal catheter happens infrequently, but are serious complications that increase the risk of contamination and peritonitis.

Catheter breakage may be due to several causes. It is frequently due to an accidental cut when changing a dressing, but also the use of sharp clamps, repeated contact with disinfectants and even the catheter barium sulphate radiopaque line may be predisposing factors.

When damage occurs in the more distal part of the catheter, it can be easily repaired by cutting away the damaged segment and inserting the transfer line segment at that point. The resulting repaired catheter is shorter, but remains functional1. However, when damage occurs at a more proximal point of the catheter, near the exit site, it is usually necessary to interrupt the procedure and remove the catheter.

We present our experience with the repair of damaged catheters without removing them and keeping patients on peritoneal dialysis (PD).

MATERIAL AND METHOD

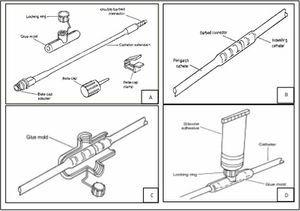

Quinton™ Peri-Patch Repair Kit (Quinton Instrument Co., Tyco Healthcare Group LP. Mansfield, MA., USA) contains a silicone catheter segment with a threaded connector at one end and a beta-cap adapter inserted into the other end. The kit also includes a plastic mould with a locking ring, a catheter plug, a clamp and sterile adhesive (Figure 1A).

The repair procedure must be performed using an aseptic technique in a sterile field. Alcohol-based disinfectants should not be used as they adversely affect the adhesive process, and catheter segments on which we need to work must be completely dry before applying the adhesive.

Repair procedure steps:

- The catheter must be clamped between the skin and the site of damage or breakage.

- Cut the catheter carefully at the site of damage or breakage with sterile scissors trying to preserve as great a length as possible.

- The catheter segment that comes in the kit is connected to the original indwelling catheter by its threaded end. The connection must be firm and secure (Figure 1B).

- Remove the clamp from the catheter and allow drainage of several ml of dialysate so as to wash away any contaminants at the new joint. Next, close the added catheter segment with the plug.

- After making sure that the point of the new connection is completely dry, mould plastic around the site securing it with the locking ring (Figure 1C).

- Sterile silicone adhesive is applied through the locking ring to fill the mould (Figure 1D).

- A new transfer line or catheter extension segment is connected, following the usual steps for this process, to the silicone segment added.

- The plastic mould can be removed after 48-72 hours.

- The manufacturer's instructions indicate that PD can be resumed after completing all the steps and if the adhesive has solidified, but we prefer to wait 24 hours before restarting the procedure.

DESCRIPTION OF THE CASES

Patient 1

Male, 63 years of age, with a self-locating catheter and on PD for one month. During an exit site dressing change, the patient accidentally cut the catheter with scissors about 5cm from the skin. After clamping the catheter, the procedure described above in the Material and Method section was performed. Prophylactic antibiotic was administered. PD was resumed normally after 24 hours and no episodes of peritonitis were recorded after nine months of follow-up (Figure 2).

Patient 2

Male, 40 years of age, with a swan neck catheter with two Dacron cuffs implanted six years earlier. After three years on PD, the external cuff was extruded as part of the treatment of a recurrent infection of the exit site. Three years later, during a periodic review, inspection revealed a small hole near the remains of the extruded outer cuff. The hole did not reach the lumen of the catheter, but to prevent complete perforation we decided to reinforce this point. To do this, we wrapped the site of the hole with the mould and filled this with silicone adhesive. The kit catheter extension segment was not necessary in this case, as there was not a complete breakage. Dialysis was not interrupted and there were no infectious complications after the procedure.

Patient 3

Female, 57 years of age, with a self-locating catheter. After four years on PD, a small interruption or disappearance of the catheter radiopaque line was seen, but careful examination of the catheter revealed no leaks. However, nine months later, the patient consulted due to dialysate leakage through a hole located just at the point where the radiopaque line had disappeared. The patient was administered prophylactic antibiotics and we proceeded to repair the catheter, using the kit catheter extension segment. No further complications were reported.

Patient 4

Male, 74 years of age, had a self-locating catheter in place for three years. External cuff extrusion was noted due to a recurrent infection of the exit site. The procedure was performed without incident, but the "shaving" of extruded cuff was difficult because the Dacron was firmly stuck to the catheter and there was a risk of inducing a perforation or rupture of the catheter. Rough and dirty remnants of the external cuff remained too close to the exit site and could cause a new infection, either by exit site irritation or colonisation. For this reason, we decided to coat them with silicone using the plastic mould (Figure 3). As there was no breakage, it was not necessary to use the kit catheter extension segment in this case and dialysis was not interrupted. The patient suffered no infection after the procedure.

Patient 5

Male, 46 years of age, on automated PD for five years with a self-locating catheter. After four years on PD, during a periodic exam a small interruption or disappearance of the catheter radiopaque line was found, but leakage of dialysate was ruled out and the procedure continued without incident. Several months later, the patient experienced a greater number of cycler alarms, mostly due to problems during drainage. A catheter inspection showed that the missing portion of the radiopaque line had increased, and the catheter collapsed at that point when suction was applied (as happens with the cycler during the drainage phase) (Figure 4A and Figure 4B). Once again, we used the repair kit, this time with some variations. We clamped the catheter near the skin and disconnected the transfer line. Then, we insufflated air through the lumen with a syringe and placed a new clamp, leaving the problem area between the clamps inflated. We placed the silicone mould around this dilated area and filled it with adhesive glue (Figure 4 Figure 4C and 4D). We put in place a new transfer line. After 24 hours, the clamps were removed and the patient resumed treatment with a significant reduction in the number of alarms.

CLINICAL SUMMARY

We have presented five repair procedures carried out on five peritoneal catheters.

The patients’ mean age (4 men and 1 woman) was 56 years, and three of them were on automated PD and two on continued ambulatory PD. The catheters had been in place for one month, six years, four years and nine months, three, and five years, respectively.

In patients 1 and 3, the broken catheters were repaired adding the kit catheter extension segment. Patients were given prophylactic antibiotic treatment not because of the repair procedure, but due to the accidental disconnection. In patients 2 and 4, the kit was used to prevent future complications. Our personal application in patient 5 eased their problems with the cycler.

None of the patients experienced peritonitis or other infectious complications or dialysate leaks after several months of follow-up.

DISCUSSION

Although PD has certain advantages with respect to haemodialysis, it continues to be underutilised. One of the reasons for this low utilisation is the high dropout rate due to technical problems related to the catheter. In many cases, the catheters are removed rather than trying to perform rescue procedures, and the patients are transferred to haemodialysis. The repair of damaged catheters is, therefore, an important procedure for keeping the patients on PD.

Catheter breakage or damage may be due to natural wear and tear of the catheter after prolonged use, although the repeated use of clamps, or repeated contact with disinfectants have also been considered predisposing factors. The application of mupirocin, used as coadjuvant treatment for exit site infection has been associated with the occurrence of permanent structural changes in the catheter, such as opacity, deformity and dilation, although damage caused by mupirocin is more often described with polyurethane catheters. Exit site colonisation and infection by gram-negative bacteria can also be a predisposing factor for catheter breakage. And silicone chemical weakening caused by interaction with iodine disinfectants can be exacerbated by mechanical stresses, eventually causing breakage. Occasionally, some batches of defective catheters can escape quality control in the production line and defective catheters are distributed to dialysis centres1-7.

That said, the most common cause of catheter damage is the use of scissors or sharp objects during dressing changes. For this reason, during initial patient training emphasis should be placed on measures to prevent catheter damage. Using scissors or other sharp objects to cut bandages near a PD catheter is clearly undesirable and should be banned. Furthermore, alcohol or iodine are no longer recommended for daily care of the exit site.

Catheter breakage almost always causes contamination and a high risk of peritonitis. Therefore, it is important to repair it quickly.

When the catheter is damaged near the exit site, use of the repair kit is an alternative to catheter removal. Although this kit has been available for many years, we have found few references to its use2-4. It is easy to use and the risk of induced peritonitis is not greater than when an extension is changed.

In summary, the repair of a damaged catheter using the repair kit extends the life of the catheter and prevents its removal, allowing the patient to continue on PD.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest related to the contents of this article.

Figure 1.

Figure 2. Catheter repaired using the kit catheter segment

Figure 3.

12486_19157_64782_en_ref.1248632237_12486_19115_55624_es_12486_figura4.doc

Figure 4.