To the Editor:

We present the case of a 40-year-old female, who was an ex-smoker until 2010, when she retook the habit. The patient suffered from lupus with joint, haematological, and pericardial manifestations; the patient also suffered from anti-phospholipid syndrome with arterial manifestations (cerebrovascular accident, renal artery stenosis, and stenosis of the arteriovenous fistula [AVF]), poorly controlled arterial hypertension, advanced chronic kidney disease (CKD) secondary to focal and segmental hyalinosis (insufficient evidence to rule out the coexistence of type V lupus nephritis), and on haemodialysis treatment since 1990. The patient received a kidney transplant in 1991, but restarted dialysis in 1998 after a recurrence of the underlying disease, which coincided with pregnancy. Severe tertiary hyperparathyroidism with regular/poorly controlled phosphorous levels for several years (variable compliance with treatment) and osteoporosis of trabecular bone (t-score: -2.5; z-score: -2.3). The patient also exhibited hyperhomocysteinemia, hyperuricemia, and a hidden hepatitis C infection with haemosiderosis. The right humerobasilic AVF was functional. Normal treatment included cinacalcet, pepsamar, calcium acetate, risedronate, folic acid, polyvitamin B1/6/12, omeprazole, allopurinol, carvedilol, hydroxychloroquine, and acenocoumarol.

CURRENT DISEASE

In September 2009, acenocoumarol was replaced with tinzaparin (anti-activated factor X: 0.8-1.2IU/ml) due to upper gastrointestinal bleeding, and the patient remained on this treatment regimen for one year. In November 2010, she developed purple lesions on the pad of the third finger of the left hand, contralateral to the AVF (Figure 1 A), which were cold and painful to the touch. Radial pulse was normal. An ipsilateral Doppler ultrasound revealed mild calcified atheromatosis of the axillary and brachial arteries, with no haemodynamically significant stenosis. During the first 24 hours, acenocoumarol was reinitiated, and topical nitroglycerin was added to the treatment regimen. An INR of 4 was reached in 72 hours, which allowed for the suspension of tinzaparin. Five days after the start of symptoms, the patient complained of intense pain in the finger and a slow progression towards cutaneous necrosis and a new lesion with similar ischaemic characteristics to the second ipsilateral finger. Treatment was started with antibiotic therapy and alprostadil (500ug i.v. over 10 doses). Dicoumarin was suspended, and tinzaparin was recommenced. We took a cutaneous biopsy, which revealed ischaemic haemorrhagic necrosis, microcirculation thrombosis, and leukocytoclast phenomena, indistinguishable from necrosis induced by coumarin or anti-phospholipid syndrome, and isolation of Enterobacter cloacae in the tissue culture (Figure 1 B).

The lesion on the 2nd finger quickly returned to normal, but the third finger progressed to necrosis and scarring with nail loss and partial amputation leaving a blind stump (Figure 1C). A trans-oesophageal echocardiogram ruled out vegetations. Protein C levels decreased over two measurements: 57% activity (n>70%). The family history analysis was negative. Protein S levels were normal. We did not measure anti-thrombin III levels due to the treatment with heparin, and did not measure anti-thrombin III antibodies due to the unavailability of this test at our centre.

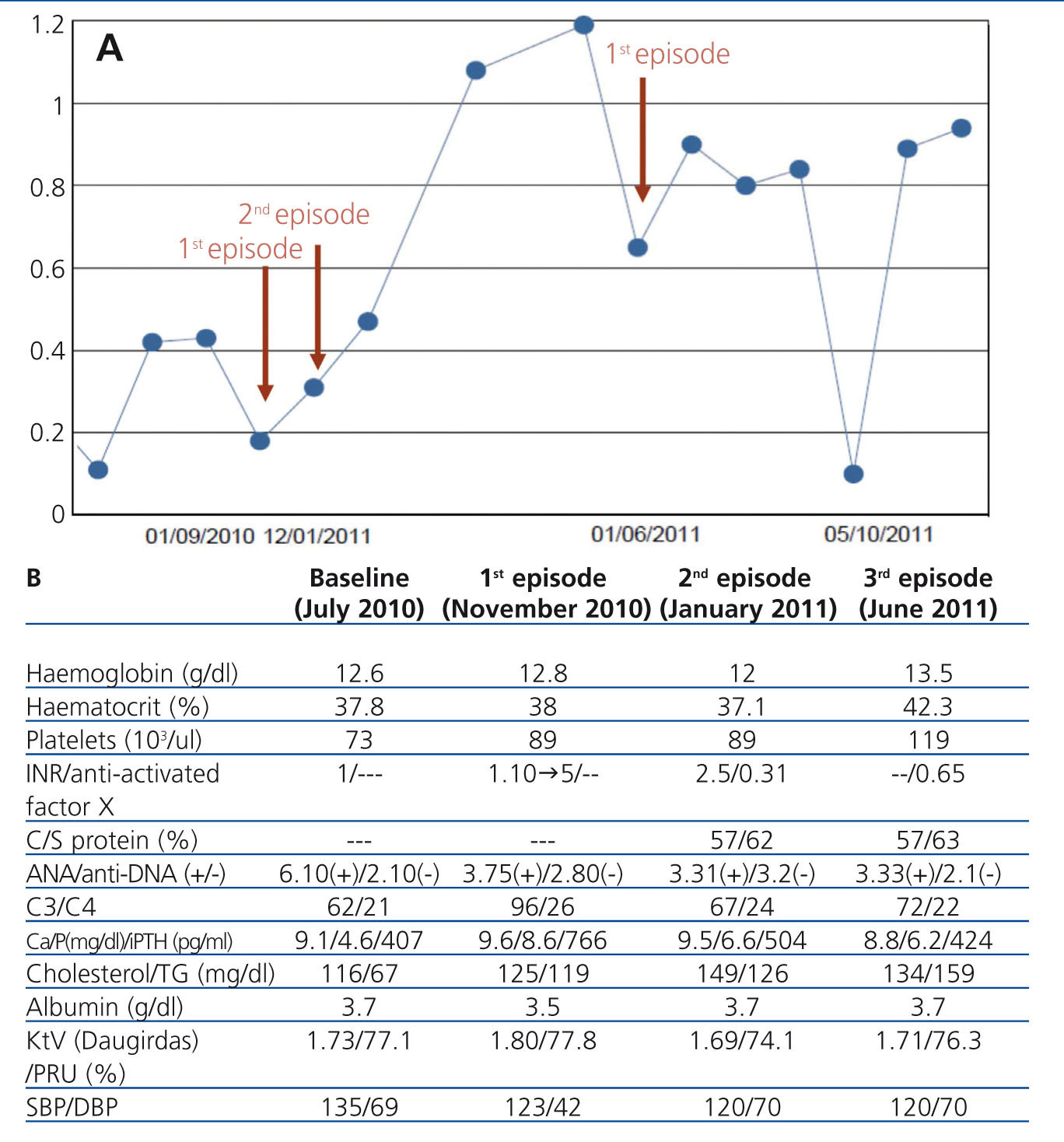

In January 2011, acenocoumarol was recommenced on a very slow and progressive regimen. Thirteen days after starting medication, the patient developed an identical set of symptoms on the fifth finger of the opposite (right) hand. Dicoumarin treatment was definitively suspended and tinzaparin was restarted (Figure 2A), and the ischaemic lesion subsided after a few days. After one week, and coinciding with a trip to a cold region, increased tobacco use, and a respiratory infection, the same symptoms appeared at the same location (fifth finger of right hand), again requiring intravenous prostaglandins and morphine. The finger finally progressed to necrosis, causing fingernail loss and amputation leaving a blind stump (Figure 1 C).

In June 2011, the patient developed similar but milder symptoms in the third finger of the right hand, this time coinciding with a haemoglobin value of 15g/dl. The patient was bled and started on alprostadil, which effectively treated the ischaemia. A Doppler ultrasound revealed marked spectral wave damping in the cubital, radial, and medial arteries just past the AVF, which indicated a phenomenon of arterial steal syndrome from the vascular access. We did not observe stenosis in the anastomosis. The brachial, radial, cubital, and medial left arteries had adequate arterial flow.

We decided against closing the vascular access given clinical improvements and no other non-catheter treatment options. During each acute episode, arterial flow decreased to 300ml/min (normal: 450ml/min). The dialysis dose was not changed significantly, with a Daugirdas Kt/V that remained constantly above 1.5, and a PRU>65%.

Parameters for lupus activity (anti-DNA and C3, C4) were negative during the first episode, and C3 decreased slightly in the second and third episodes. We did not measure anti-phospholipid antibodies due to the scarce relationship these levels have with the patient’s symptoms, and due to the administration of anticoagulation therapy (Figure 2B).

DISCUSSION

CKD is considered to be a pro-atherosclerotic condition per se. Poor control of calcium-phosphorous metabolism in haemodialysis patients exponentially increases vascular risk, on a similar scale to tobacco use or diabetes.1 In a similar manner, SLE and APS and their treatments (steroids, anti-calcineurinics) contribute to endothelial dysfunction in these patients,2 in addition to the recent association between these diseases and activated protein C deficiency or resistance.3,4 Patients with deficiencies for this protein appear to be more susceptible to cutaneous necrosis when treated with dicoumarin.5

These factors, alone or in combination, can compromise distal perfusion. The coexistence of all of these factors and tobacco use, exposure to cold, haemoconcentration, hyperhomocysteinemia, and functional arterial steal syndrome due to the vascular access can constitute an “explosive mix” that can cause progression and recurrence of the digital cutaneous necrosis described here.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest related to the contents of this article.

Figure 1. Macro and microscopic images of lesions

Figure 2. Laboratory parameters