Tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) is a rare, hereditary, multisystemic disease with a broad phenotypic spectrum. Its management requires the collaboration of multiple specialists. Just as in the paediatric age, the paediatric neurologist takes on special importance; in adulthood, renal involvement is the cause of the greatest morbidity and mortality. There are several recommendations on the general management of patients with TSC but none that focuses on renal involvement. These recommendations respond to the need to provide guidelines to facilitate a better knowledge and diagnostic-therapeutic management of the renal involvement of TSC through a rational use of complementary tests and the correct use of available treatments. Their elaboration has been based on consensus within the hereditary renal diseases working group of the S.E.N./REDINREN (Spanish Society of Nephrology/Kidney Research Network). It has also counted on the participation of non-nephrologist specialists in TSC in order to expand the vision of the disease.

El complejo esclerosis tuberosa (CET) es una enfermedad rara, hereditaria, multisistémica y con un amplio espectro fenotípico. Su manejo requiere de la colaboración de múltiples especialistas. Así como en la edad pediátrica cobra un especial relieve el neurólogo pediatra, en la edad adulta la afectación renal es la causante de la mayor morbimortalidad. Existen diversas recomendaciones sobre el manejo general del paciente con CET pero ninguna que se centre en la afectación renal. Las presentes recomendaciones responden a la necesidad de proporcionar pautas para facilitar un mejor conocimiento y manejo diagnóstico-terapéutico de la afectación renal del CET mediante un uso racional de las pruebas complementarias y el empleo correcto de los tratamientos disponibles. Su elaboración se ha basado en el consenso dentro del grupo de trabajo de enfermedades renales hereditarias de la S.E.N./REDINREN. Ha contado con la participación de especialistas en CET no nefrólogos también con el fin de ampliar la visión de la enfermedad.

Tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) (ORPHA 805) is a rare (1/6,000-8,000), hereditary, multisystemic disease with a broad phenotypic spectrum.1 It is caused by mutations in the TSC1 and TSC2 genes (OMIM #191100, #613254). Adequate diagnostic/therapeutic management of TSC requires coordination between multiple paediatric and adult specialities: obstetrics, genetics, neurology, nephrology, urology, cardiology, ophthalmology, internal medicine, psychiatry, dermatology, dentistry, respiratory medicine and radiology. There are various management recommendations which take into account the systemic effects of the disease, but none focuses on managing renal involvement.2–4 The recommendations we present here are a response to the need for guidelines to improve both understanding and the diagnostic/therapeutic management of renal involvement of TSC, through a rational use of investigations and the correct use of available treatments. They are based on consensus from the hereditary kidney disease working group of the Sociedad Española de Nefrología/Red de Investigación Renal (SEN/REDINREN) [Spanish Society of Nephrology/Renal Research Network]. We also benefited from the participation of non-nephrology specialists in TSC, that helped to broaden the vision of the disease, but without diverting the focus from the renal aspects. Levels of evidence are specified according to the methodology of the Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (University of Oxford) (http://www.cebm.net/?o=1025). The authors are listed in alphabetic order.

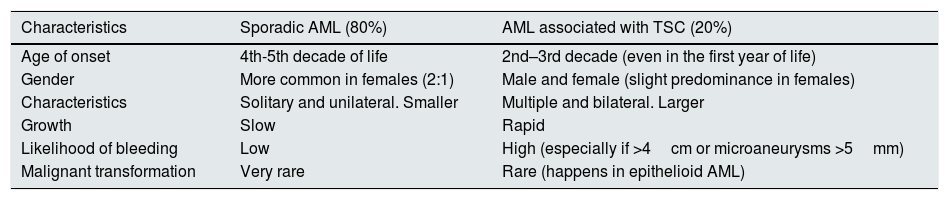

AngiomyolipomasIntroductionAngiomyolipomas (AML) are benign tumours derived from endothelial cells (perivascular epithelioid cells; PEComas).5 They are composed of adipose tissue, smooth muscle and blood vessels.6 AML are the most common renal lesions in patients with TSC (prevalence of 55–80%).7 In the general population, 80% of AML are sporadic and have differential characteristics with the AML associated with TSC7 (Table 1).

Differential characteristics between sporadic AML and AML associated with TSC.

| Characteristics | Sporadic AML (80%) | AML associated with TSC (20%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age of onset | 4th-5th decade of life | 2nd–3rd decade (even in the first year of life) |

| Gender | More common in females (2:1) | Male and female (slight predominance in females) |

| Characteristics | Solitary and unilateral. Smaller | Multiple and bilateral. Larger |

| Growth | Slow | Rapid |

| Likelihood of bleeding | Low | High (especially if >4cm or microaneurysms >5mm) |

| Malignant transformation | Very rare | Rare (happens in epithelioid AML) |

They increase both in size and in number with age.8 They are less common, but not unheard of, in children. They are the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in adults with TSC.9,10 AML grow faster in women on oestrogen treatment and pre-pubertal girls, suggesting that their development may be affected to some extent by hormones.8 The main complication is bleeding, which occurs mainly in lesions >4cm or in microaneurysms >5mm,11,12 and the risk may increase during pregnancy. The AML associated with TSC have a rupture and haemorrhage rate ranging from 21% to 100%, according to the published series.

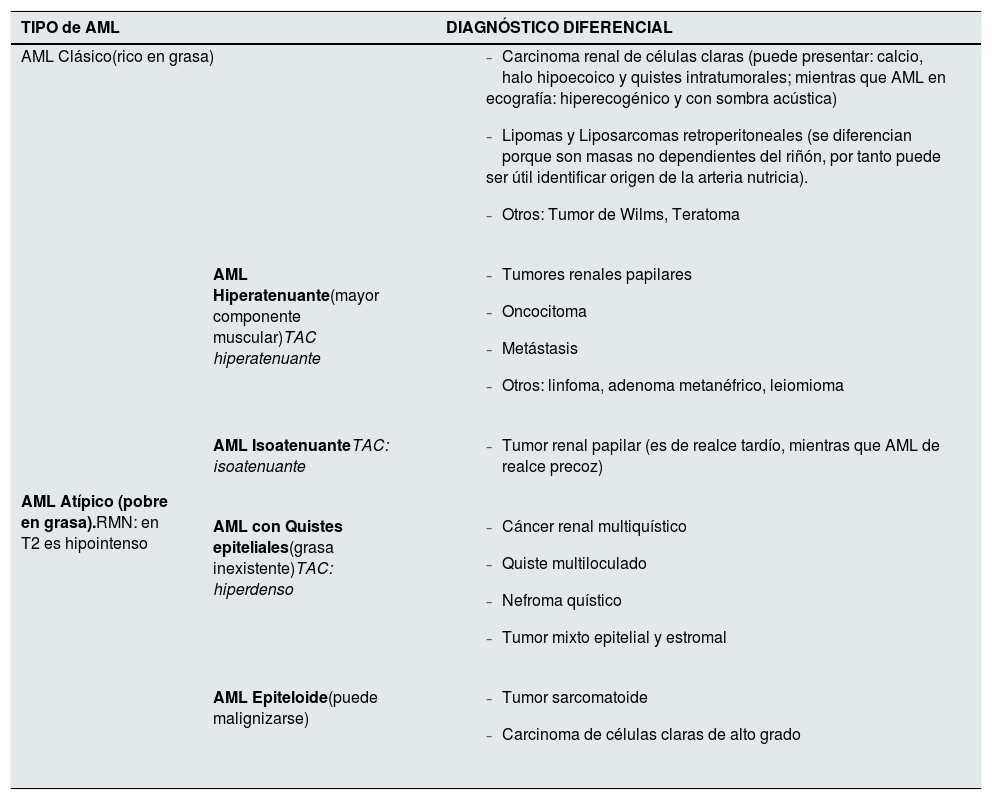

There are two histological types of AML: classic (fat-rich) and, in up to a third of cases, atypical (fat-poor). The epithelioid variant is an atypical AML with more than 10% epithelioid cells (cells with abundant eosinophilic and granular cytoplasm), which can undergo malignant transformation13 (Table 2).

Types of AML and differential diagnosis.

| TIPO de AML | DIAGNÓSTICO DIFERENCIAL | |

|---|---|---|

| AML Clásico(rico en grasa) |

| |

| AML Atípico (pobre en grasa).RMN: en T2 es hipointenso | AML Hiperatenuante(mayor componente muscular)TAC hiperatenuante |

|

| AML IsoatenuanteTAC: isoatenuante |

| |

| AML con Quistes epiteliales(grasa inexistente)TAC: hiperdenso |

| |

| AML Epiteloide(puede malignizarse) |

| |

Adapted from Buj Pradilla et al., 2017.14

Diagnosis is made from imaging tests: ultrasound, computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Ultrasound is fast and accessible, and useful as a first approach in TSC. However, it is not very accurate in small and exophytic AML, which can be confused with perirenal fat. It is also observer-dependent. A hyperechogenic lesion with suspected AML in a patient with TSC must be confirmed with CT or MRI.14

On CT, the tissue has reduced density with negative attenuation coefficient values. CT has high precision to detect small amounts of fat, with slices as thin as 1.5mm.15 In clinical practice, the ellipsoid method can be used to measure the volume.14

CT or MRI angiogram with vascular reconstruction is the method of choice to obtain vascular mapping of the lesion as a preventive measure in AML>3cm or after active bleeding to locate the bleeding point. In these cases, CT is more accurate than MRI.

MRI is the technique of choice for initial diagnosis and follow-up. Fat appears as a hypersignal in T1 and less in T2, with hypointensity in fat-saturated T2-weighted sequences.16 In children, it is usually performed with sedation and in conjunction with brain MRI.14

Differential diagnosisThe differential diagnosis of AML is made with retroperitoneal tumours and malignant renal tumours17,18 (Table 2). It is particularly complicated in AML where intra-tumour fat is not detected. IN case of doubts, a biopsy of the lesion should be obtained.14,19

Follow-upAML require radiological follow-up due to the risk of retroperitoneal bleeding and malignancy (very rare).

In asymptomatic AML<3cm, follow-up, preferably with annual MRI scans, is recommended. If the lesion remains stable, follow-up intervals can be extended to 1–3 years. Ultrasound can be alternated with MRI for follow-up.3,4

Monitoring every six months with MRI is recommended in atypical, fast-growing lesions or in women who start oestrogen therapy.

Recommendations- 1

Perform MRI on diagnosis of TSC to identify AML that could go unnoticed on ultrasound (B).

- 2

Subsequently, follow-up every 1–3 years with MRI/ultrasound according to patient characteristics. MRI is recommended for greater accuracy, but in stable lesions it can be alternated with ultrasound (C). Try to avoid CT due to cumulative radiation, especially in paediatric patients (B).

- 3

CT angiogram is reserved for vascular mapping in AML>3cm to rule out microaneurysms (D) or acute bleeding to locate the bleeding point (C).

- 4

If in doubt of the benign nature of atypical AML, diagnostic fine-needle aspiration biopsy is recommended (C).

TSC is a disease with great phenotypic variability and multisystemic involvement. The organs most commonly affected are brain, kidney, skin, lung and eyes. The clinical manifestations are progressive and change with age. Some of the complications are life-threatening, so it is essential a protocol of clinical follow-up.

All patients with tuberous sclerosis should have protocolised monitorization of the most commonly affected organs to limit the onset of complications, according to the following recommendations.3,4,20

Recommendations- 1

Annual monitoring of blood pressure (BP), full lab analyses with renal function and proteinuria/microalbuminuria (B).

- 2

Neurological check-up: baseline brain MRI. Patients under the age of 25, those with symptoms (epilepsy, intellectual retardation or psychiatric disorders) or complications on MRI (subependymal giant cell astrocytoma [SEGA], hydrocephalus) should be referred to neurology (A).

- 3

Respiratory check-up: high-resolution chest CT scan for all patients with respiratory symptoms and for women over the age of 18 regardless of being asymptomatic. Refer patients with lesions or symptoms to the neumology service (A).

- 4

Annual dermatology and dental revisions. Early action on symptomatic lesions (A).

- 5

Heart: annual electrocardiogram and baseline echocardiogram. In cases with symptoms or abnormalities in the complementary tests, refer to cardiology (A).

- 6

Baseline ophthalmology examination; if lesions are detected, annual follow-up is recommended (B).

- 7

Genetics: family counselling in all cases; in individuals of reproductive age and if there are doubts about diagnosis, perform genetic testing (A).

- 8

There is no evidence to support other routine tests, unless there are specific symptoms (C).

- 1

Investigations to be used:

- 2

In children, ultrasound and MRI are recommended, with CT only as an exception (A).

- 3

In adults, the recommendation is essentially MRI/ultrasound, according to the characteristics of the lesions and the patient (A).

- 4

CT is much more sensitive than MRI for detecting microaneurysms and more accurate in measuring them (motion artefacts in MRI).

- 5

If the lesions are stable, try to keep CT scans to a minimum to avoid radiation.

- 6

Perform MRI whenever possible (absence of microaneurysms to assess, no contraindications for MRI) (D).

- 7

Perform CT scan instead of MRI if the patient: has apnoea and cannot cooperate; has claustrophobia; or is contraindicated due to wearing devices not compatible with MRI.

- 8

If there are symptoms that suggest bleeding (acute/active or chronic): CT without contrast, followed by biphasic CT with contrast (arterial and venous phases) (B).

- 9

If there are microaneurysms, alternate MR angiography and biphasic CT (arterial and venous), as they are often not visible in MR angiography. If MRI shows significant growth of AML, do CT angiography to assess microaneurysms (D).

- 10

If it is necessary to administer iodinated contrast in the CT scan and the patient has a GFR≤30mL/min/1.73m2, applying a nephroprotection protocol is recommended (B).

- 11

It is recommended not to perform MRI with gadolinium if GFR≤30mL/min/1.73m2.

- 12

Cysts do not require specific follow-up, but whenever AML check-ups are performed, the presence of cysts should be assessed, and whether they are simple or complicated with bleeding, infection or neoplasm. If the patient only has cysts, perform an ultrasound scan and, if a complicated one is detected, investigate preferably by MRI to avoid CT radiation (A).

- 13

If there is an excessive number of lesions (cysts or AML), measuring the overall renal volume for monitoring purposes is recommended (C).

- 14

If there is radiological suspicion of possible malignancy (minimal-fat AML), take a biopsy and then continue with the usual follow-up. If no biopsy is performed but it is decided to monitor, follow-up every six months (D).

- 15

The trend in the radiological management of AML in which response to treatment has been demonstrated should be to minimise the frequency of radiological examinations as far as possible to avoid long-term effects of contrasts and radiation (B).

AML associated with TSC have a high rate of rupture and haemorrhage and are frequently associated with a high morbidity in these patients.10 The greatest risk of bleeding is with a size larger than 4cm or microaneurysms >5mm, so patients with these characteristics need to have treatment.21

In view of the chronic and recurrent nature of these tumours, all treatment will aim to preserve renal function as far as possible.4

Emergency treatmentIn acute haemorrhage, the treatment of choice is transarterial embolization,21 which has an efficacy of 93%.22 This treatment is associated with the onset of post-embolisation syndrome (nausea, pyrexia and pain for 72h) in 35% of patients.22 Although both nephrectomy and embolisation will resolve the condition, the risk of renal failure is seven times higher with nephrectomy.23

Due to the risk of renal failure, nephrectomy should be avoided provided the emergency permits and vascular radiology techniques are available.4,21

In acute rupture associated with pregnancy, the treatment of choice remains embolisation. In certain cases, one option is emergency caesarean section and subsequent embolisation.24,25

Non-emergency treatmentSelective embolisationScheduled embolisation of AML was the treatment of choice for years, but has now been replaced by mTOR inhibitors.4,21 The success rate of embolisation is very high,22 achieving a decrease in size, pain and the associated symptoms (approximately 50%24). Renal function is usually maintained, and only in 3.3% of patients is it associated with a deterioration.23 However, AML regrowth is possible, with a second AML embolisation being required in 20%–80% of cases.22

The more embolisations, the greater the risk of renal failure.26

As far as the material used is concerned, particles larger than 150μm are preferred due to their efficiency and the lower risk of distant emboli.27

CryoablationThe use of ablation by freezing derives from its use in renal tumours of less than 4cm in size, although it has been used occasionally for larger tumours.28 For the treatment of AML, efficacy of up to 100% has been reported, with the possibility of hospital discharge the next day, but there is insufficient information about complications.24 It is an attractive alternative, but details are still lacking to place it above embolisation.

Radio-frequency or microwaveThe use of these types of energy has also been studied and published in limited series, with efficacy rates above 78%,29,30 but associated with significant side effects such as bleeding, nerve damage and hollow viscera fistulas. For this reason, this treatment is also kept as an alternative to embolisation.21

SurgeryCurrently, 13% of patients with TSC and AML have surgery, either radical (5%) or partial (8%) nephrectomy.29 Because of the high associated rate of renal failure, both partial and radical nephrectomies have been replaced by selective embolisation.23

Partial nephrectomy in these patients is more common than radical, following the objective of preserving renal function, but almost 45% of them need a second partial,29 or even a subsequent radical, nephrectomy.

Active surveillanceIn all the published series, the risk of bleeding is minimal when the AML is less than 3cm in size, so surveillance is the norm in these cases, with ultrasound or MRI every two years.14

When the tumour is larger than 3cm in size, 50% may become symptomatic, with risk factors being the presence of microaneurysms >5mm or rapid growth (>0.25cm/year),12 so starting treatment is recommended.4,21

Recommendations- 1

Emergency treatment.

- 2

The treatment of choice is transarterial embolisation (B).

- 3

An alternative to embolisation is radical or partial nephrectomy (B).

- 4

Non-emergency invasive treatment.

- 5

Selective embolisation.

- lowerRoman6

Second-line option of choice after treatment with mTOR (B).

- lowerRoman7

Material >150μm should be used to prevent migrations (C).

- 8

Cryoablation

- lowerRoman9

Alternative to the traditional options (D).

- 10

Radio-frequency or microwave

- lowerRoman11

Alternative to the traditional options (D).

- 12

Surgery.

- lowerRoman13

Surgery is the alternative only when minimally invasive options fail due to its aggressiveness and loss of renal parenchyma (B).

- 14

Follow-up.

- lowerRoman15

AML less than 3cm in size associated with tuberous sclerosis should be monitored (B).

- lowerRoman16

If there is growth of more than 0.25cm/year or AML larger than 3cm in size, active treatment should be offered (C).

- •

Indication. Everolimus is indicated for the treatment of adult patients with AML associated with TSC who are at risk of complications (based on factors such as tumour size or the presence of multiple or bilateral tumours) but who do not require immediate surgery. It is usually prescribed in lesions larger than 3cm in size. The evidence is based on the analysis of the change in the sum of the volume of the AML, where a permanent reduction in the size of the lesions has been demonstrated.31,32

- •

Dose. The recommended dose is 10mg of everolimus once a day according to the data sheet, although it seems reasonable to adjust the dose according to plasma levels. Treatment should continue as long as there is clinical benefit or until unacceptable toxicity occurs. If the patient forgets to take a dose, they should not take an additional dose, but take the next dose according to the prescribed schedule. Management of suspected serious or intolerable adverse reactions may require a dose reduction and/or a temporary discontinuation of the treatment with everolimus. For mild adverse reactions no dose adjustment is usually required. If a dose reduction is required, the recommended dose is approximately 50% lower than the daily dose previously administered. For dose reductions below the lowest available dose, dose administration should be considered every other day (http://www.emea.europa.eu/ema).

- •

Monitoring

- a)

Imaging. The most usual procedure is to assess the treatment by taking scheduled volumetric measurements of the largest renal lesions and the total size of the kidney using MRI or CT, depending on availability.14 Annual monitoring by MRI is recommended, allowing longer intervals when stability is achieved.

- b)

Laboratory tests. Use of everolimus does not cause any change in the usual clinical parameters which help to assess its effectiveness. However, it can cause some biochemical alterations which need to be monitored (albuminuria, dyslipidaemia, hypophosphataemia, increased LDH). These will be discussed in the following section. In clinical trials aimed specifically at the treatment of AML, plasma levels of everolimus were not monitored or used to guide treatment. However, the Spanish Guidelines for the Management and Treatment of Tuberous Sclerosis recommend that levels should be checked.4 This would be essential, at least at the beginning of treatment, because very low levels can be found due to concomitant treatment with inducers or inhibitors of CYP3A4 or antiepileptic drugs, and after a change in liver status (Child-Pugh).

- •

Adverse effects: description and management

- c)

Stomatitis is the most common complication, but not serious, and is usually recurrent, but gradually decreasing in intensity. Treatment is symptomatic with normal saline or alcohol-free rinses (with hyaluronic acid; e.g. Aloclair®). Topical analgesics and corticosteroids may be used, but antifungals are not recommended.

- d)

Infections. Take a full medical history and ask for viral markers prior to treatment. Management will depend on each case, but if there is systemic fungal invasion, treatment should be discontinued immediately. In cases of active hepatitis B or C treatment should be agreed with the hepatologist.33

- e)

Dyslipidaemia. Treatment according to standard consensus guidelines, including: control of risk factors, dietary treatment and physical exercise, and pharmacological treatment with statins, if indicated. There are no pharmacological interactions between everolimus and statins or fibrates.

- f)

Hypophosphataemia. Treat mild hypophosphataemia (<2.5mg/dl) with oral phosphate: 30−100mg/kg/day in three or four divided doses, according to response. Hypophosphataemia <1mg/dl requires hospitalisation, intravenous phosphate and discontinuation of the treatment.33

- g)

Proteinuria and renal failure. Albuminuria and renal function need to be monitored. If a patient develops albuminuria, they may be treated with angiotensin receptor antagonists. In severe proteinuria, treatment should be discontinued. The effect on renal function has not been fully assessed in the long term.34

- h)

Use of everolimus is often accompanied by microcytic anaemia, thrombocytopenia and progressive lymphopenia, but only rarely do they lead to the medication being discontinued.35 Haematological toxicity is concentration-dependent; should it occur, it may indicate an interaction or failure to take medication. It is advisable to determine the concentration at which the toxicity appeared, in order to restart a new regimen in therapeutic range (Cmin ∼ 5ng/mL). Management is similar to any other cytopenia.36

- i)

Amenorrhoea. It seems that amenorrhoea can be caused by mTOR inhibition, which may play an important role in controlling the onset of puberty. It is important to monitor for defects or dysfunctions in growth, development or sexual maturation. Most cases are transient, manageable and do not lead to interruption of treatment. Patients should be referred to gynaecology to rule out other causes.

- j)

Non-infectious pneumonitis is accompanied by nonspecific respiratory signs and symptoms such as cough, dyspnoea, hypoxaemia and pleural effusion, and a more thorough follow-up with the necessary pulmonary function tests is recommended, according to the patient's condition. Confirm the diagnosis of non-infectious pneumonitis with sputum and blood cultures in symptomatic cases. Asymptomatic cases do not require interruption of treatment. Adjust the dose of everolimus in mildly symptomatic cases. In more severe cases, discontinuation of treatment and use of corticosteroids is indicated.37

- k)

Everolimus can alter the wound healing process. Discontinuing the drug is therefore recommended in the peri-operative period, especially in older patients and patients with diabetes, malnutrition or high body mass index (BMI). Additionally, caution should be taken in patients receiving concomitant treatment with corticosteroids and/or anticoagulants.

- l)

CYP3A4 or PgP inducers can lower everolimus blood concentrations. Concomitant treatment with potent CYP3A4 inhibitors such as ketoconazole and other azoles, clarithromycin, telithromycin, nefazodone or HIV protease inhibitors is not recommended.38

- 1

Treatment with everolimus is recommended for adult patients with renal AML associated with TSC who are at risk of complications (AML>3cm) at an initial dose of 10mg/day (A).

- 2

It is suggested that the effects of the treatment be monitored with yearly/two-yearly imaging tests (B).

- 3

It is suggested that levels of the drug be determined at the beginning of treatment, after any change of dose due to concomitant treatment with inducers or inhibitors of CYP3A4 or antiepileptic drugs, and after a change in liver status (Child-Pugh) (C).

- 4

It is suggested that everolimus plasma levels be maintained in the range of 4–10ng/mL (D).

- 5

It is suggested treating stomatitis symptomatically (D).

- 6

In the case of patients with active hepatitis B or C, it is suggested discussing the treatment with a hepatologist (C).

- 7

In all cases of symptomatic infection it is recommend stopping everolimus and restarting treatment with half the dose (C).

- 8

It is suggested treating dyslipidaemia according to standard consensus guidelines (D).

- 9

It is suggested treating hypophosphataemia with oral or intravenous phosphorus supplements according to the severity (D).

- 10

It is recommend monitoring albuminuria and renal function (B).

- 11

It is suggested managing any type of cytopenia with the standard treatments (C).

- 12

It is recommend determining the concentration at which the haematological toxicity appeared, in order to restart a new regimen in therapeutic range (B).

- 13

It is suggested referring cases of amenorrhoea to gynaecology to rule out adjuvant causes (D).

- 14

An immediate X-ray is recommended whenever there are respiratory symptoms. After a first episode of pneumonitis, we recommend chest X-rays every six weeks for the first six months after restarting the treatment (D).

- 15

It is recommend discontinuing everolimus and treating with corticosteroids in severe cases of correctly diagnosed non-infectious pneumonitis (B).

- 16

It is recommend discontinuing the drug in the peri-operative period until complete healing has taken place (B).

- 17

It is suggested that everolimus should be used with caution in patients on concomitant treatment with corticosteroids and/or anticoagulants (D).

- 18

Concomitant treatment with potent CYP3A4 inhibitors, such as ketoconazole and other azoles, clarithromycin, telithromycin, nefazodone or HIV protease inhibitors, is not recommended (B).

Renal cysts in TSC are considered a minor criterion and are the second most common renal manifestation after AML.2 The incidence is around 50% of patients.8,39 They are more common in patients with mutation in the TSC2 gene than in TSC1, especially if the TSC2 mutation is truncated.7,39 They can present as glomerulocystic disease, single or multiple simple cortical cysts or with cystic nephromegaly associated with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. They are usually asymptomatic, but occasionally, if large, they can rupture and bleed.

DiagnosisDiagnosis is made by ultrasound scan. MRI or CT can be useful in the case of uncertainty.3,14

Differential diagnosis of complicated cysts- •

Hamartomatous renal polyps.

- •

Renal cell carcinoma.

- •

Atypical renal AML.

Uncomplicated cystic lesions do not require strict monitoring. They will be checked in the AML follow-up imaging test. They do not require specific treatment, have little clinical impact and do not usually need complex management.3,4

Recommendations- 1

We suggest the renal cysts be monitored radiologically in the imaging tests performed for follow-up of the AML (C).

- 2

The renal cysts in TSC do not require specific treatment (C).

A minority (∼ 2%) of patients with TSC have what is known as TSC2/PKD1 contiguous gene syndrome (autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease [ADPKD] type 1 with tuberous sclerosis, OMIM: 600273; ORPHA: 88924) caused by large deletions which affect the TSC2 and PKD1 genes, located next to each other on chromosome 16. The deletion of both genes is expressed with a characteristic phenotype of severe and early onset ADPKD, associated with clinical manifestations suggestive of TSC.40

The estimated prevalence of this condition is <1/1,000,000, and it is inherited with a theoretical autosomal dominant transmission pattern, although it is uncommon for affected individuals to reproduce.

DiagnosisThe suspected diagnosis is based on detection before birth, at birth or during the first months of life of enlarged kidneys, with multiple cortical cysts of variable sizes, suggestive of a very early and severe ADPKD.40 Patients usually have difficult-to-control hypertension and/or a reduced glomerular filtration rate, along with symptoms or signs suggestive of TSC, usually neurological, given their early age.2 The renal phenotype is more severe than usual in patients with TSC, with the presence of multiple cysts on ultrasound, increasing nephromegaly and progression to advanced chronic kidney disease (CKD) in the young adult.41

Typically, the lack of a family history of ADPKD, the progression and severity of the ADPKD, and the clinical signs and symptoms of TSC, lead to the conclusion of TSC2/PKD1 contiguous gene syndrome. The definitive diagnosis is established by genetic testing with the finding of a deletion that affects the two genes described.2

Differential diagnosisOther conditions which involve renal cysts, such as autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease and cystic dysplasia due to mutations of the HNF1b gene need to be excluded.42

Follow-upPatients with TSC should be managed according to the expert recommendations,3,4 with the symptomatic treatment required by the severity and progression of the associated ADPKD.

Recommendations- 1

Patients with TSC2/PKD1 contiguous gene syndrome should be followed up by the paediatric nephrologist (A).

- 2

Strict monitoring of BP is recommended (B).

- 3

The management of CKD is similar to that for other aetiologies. The assessment for renal replacement therapy should include the patient's neurocognitive status and be made on an individual basis (D).

- 4

We recommend that patients are monitored by paediatric neurology and later by neurology (B).

The prevalence of hypertension (HTN) in patients with TSC under the age of 25 is up to 25%. It is more common in patients with mutations in the TSC2 gene and in patients with more lesions in the kidneys,43 especially those with TSC2/PKD1 contiguous gene syndrome.

BP should be measured in the initial assessment of a patient diagnosed with TSC, and subsequently monitored annually.21 The target BP in monitoring should be the same as in the hypertensive population with kidney disease (<140/90mmHg in the clinic and <135/85mmHg by self-measured BP monitoring at home or BP below the adjusted 90th percentile for size and gender in a paediatric patient).44,45 Monitoring of BP is essential to prevent the progression of CKD.

The renin-angiotensin system inhibitors are the first-choice antihypertensive drugs.21 In addition, the presence of type 1 angiotensin II receptors has been demonstrated in AML and, experimentally, blocking of angiotensin II potentially seems to have a therapeutic effect in this area.46 In patients treated with everolimus, given the higher incidence of angioedema in association with ACE inhibitors, treatment with ARB should be given.47,48 In children with infantile spasms, treatment with corticotropin may induce HTN; in this context, initial diuretic treatment may be sufficient.

Recommendations- 1

BP should be assessed at diagnosis and subsequently, at least annually (B).

- 2

Target BP in the clinic should be <140/90mmHg and by self-measurement, <135/85mmHg (D), or <90th percentile for size and gender in the case of children and adolescents.

- 3

The renin-angiotensin system inhibitors are the first-choice antihypertensive drugs (C).

The destruction of the renal parenchyma due to the presence of AML and cysts in the renal tissue, combined with the invasive treatments of AML (embolisation and partial and total nephrectomies), are the main determinants in the development of CKD. Among patients with TSC, 40% have CKD stage 3 (or more advanced) by the age of 45-54.9,21 Kidney disease is more prevalent in patients with TSC2 mutations, and especially in patients with TSC2-PKD1contiguous gene syndrome, who usually progress towards advanced renal failure during their teenage years.43

Renal function should be assessed at diagnosis and then annually in adult patients. The management of CKD-related complications should be the same as for other causes of kidney disease (https://kdigo.org/guidelines/anemia-in-ckd/;https://kdigo.org/guidelines/ckd-evaluation-and-management/; https://kdigo.org/guidelines/ckd-mbd/; https://kdigo.org/guidelines/lipids-in-ckd/).

There are no formal contraindications in relation to the choice of renal replacement technique. In transplanted patients it seems reasonable to include mTOR inhibitors in their immunosuppressive therapy, in view of their benefits in relation to the manifestations of the disease.

Recommendations- 1

Renal function should be assessed at diagnosis and subsequently at least annually in adults (B).

- 2

The management of CKD-related complications should be the same as for other causes of CKD (D).

- 3

There are no formal contraindications in terms of choosing the type of renal replacement therapy (D). In transplanted patients, we recommend including mTOR inhibitors in their immunosuppressive therapy (D).

Because of the multisystemic nature of the disease, TSC requires coordination among all the healthcare professionals involved. The healthcare professionals need to set up a Committee specialised in TSC and meet periodically to discuss and agree on consensual actions for the different cases being monitored by the team.

Patient follow-up is based on the recommendations described above. To properly coordinate the follow-up, the figure of the nurse case manager is very useful. The manager of clinical cases is responsible for ensuring correct planning of the diagnostic and follow-up tests, and the appointments with the team's different specialists according to protocol. The case manager also sets up the communication network between the healthcare professionals to help ensure smooth and efficient monitoring. Their role is fundamental in the transition from paediatrics and they are the first filter for the doubts and concerns of the patient and their relatives.

Recommendations- 1

We recommend the creation of multidisciplinary TSC teams (B).

- 2

We suggest the need for a manager of clinical cases (B).

This work was partially funded by ISCIII (Instituto de Salud Carlos III [Carlos III Health Institute]): RETIC REDINREN RD16/0009 FIS FEDER FUNDS (PI15/01824, PI18/00362) and (AGAUR2014/SGR-1441).

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Ariceta G, Buj MJ, Furlano M, Martínez V, Matamala A, Morales M, et al. Recomendaciones de manejo de la afectación renal en el complejo esclerosis tuberosa. Nefrologia. 2020;40:142–151.