Diabetes mellitus is the leading cause of chronic kidney disease (CKD) in our country. The objective was to estimate the global prevalence and by health areas of CKD in the diabetic population of Extremadura.

MethodsObservational, longitudinal retrospective study in the diabetic population attended in the Extremadura Health System in 2012−2014. A total of 90,709 patients ≥18 years old were studied. The estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation (CKD-EPI). The presence of CKD was was defined as follows: an eGFR <60ml/min/1.73m2 in a time period≥of three months or the presence of renal damage, as evaluated by an urine albumin-creatinine ratio (UACR) ≥30mg/g, with or without reduced eGFR, also in a time period ≥ of three months.

ResultsThe overall prevalence of CKD was 15.6% (17.5% in women and 13.7% in men) and it was higher in the province of Cáceres (17.0%) than in Badajoz (14.8%, p<0.001), with the lowest prevalence in the Navalmoral de la Mata health area (13.0%) and the highest in Plasencia (17.8%, p<0.001). The prevalence of CKD defined without the need for confirmation of the sustainability of kidney damage or decreased eGFR was 26.1% (29.3% in women and 22.9% in men), which represents an overestimation of the prevalence of 67%.

ConclusionsThe prevalence of CKD in Extremadura's diabetic population is lower than usually referred to and differs significantly between its health areas.

La diabetes mellitus es la principal causa de enfermedad renal crónica (ERC) en nuestro país. El objetivo fue estimar la prevalencia global y por áreas sanitarias de ERC en la población diabética de Extremadura.

Pacientes y métodosEstudio observacional, longitudinal, retrospectivo en la población diabética atendida en el Sistema Extremeño de Salud durante el período 2012−2014. Se incluyeron 90.709 pacientes ≥18 años. El cálculo del filtrado glomerular estimado (FGe) se realizó mediante la ecuación CKD-EPI (derivada de la ecuación desarrollada por la Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration) y se calculó el cociente albumina/creatinina en orina (CAC). Se consideró paciente con ERC a todo aquel que en su última analítica tenía un FGe <60mL/min/1.73m2 y/o un CAC≥30mg/g, confirmados en una determinación previa separada al menos por 3 meses.

ResultadosLa prevalencia global de ERC fue del 15,6% (17,5% en mujeres y 13,7% en varones) y fue mayor en la provincia de Cáceres (17,0%) que en la de Badajoz (14,8%, p<0,001), encontrándose la menor prevalencia en el área sanitaria de Navalmoral de la Mata (13,0%) y la mayor en la de Plasencia (17,8%, p<0,001). La prevalencia de ERC definida sin necesidad de confirmación de la sostenibilidad del daño renal o del FGe disminuido fue del 26,1% (29,3% en mujeres y 22,9% en varones) lo que supone una sobreestimación de la prevalencia del 67%.

ConclusionesLa prevalencia de ERC en población diabética extremeña es menor a la referida habitualmente y difiere significativamente entre sus áreas sanitarias.

The incidence and prevalence of diabetes mellitus (DM) has increased all over the world, fundamentally due to type 2 diabetes (DM2). This worldwide increase in the number of diabetics has had a major impact on the development of diabetic kidney disease, one of its most frequent complications.1 Both chronic kidney disease (CKD) and DM2 are highly prevalent diseases and constitute a major public health problem. Patients with CKD and DM are a special risk group, as they present major morbidity and mortality, fundamentally cardiovascular mortality, and a greater risk of hypoglycaemias. The incidence of cardiovascular events in patients with CKD is very high and similar to that of patients with ischaemic heart disease; it is being accepted that CKD behaves as a coronary equivalent and therefore the patients that suffer from it are candidates for secondary cardiovascular prevention measures.2

The estimated prevalence of CKD worldwide in people >30 years is 7.2%3 and in Spain is 6.8%,4 whereas the prevalence of CKD in diabetic patients ranges from 20% to 40% depending on the country and the diagnostic criteria used.1,5–7 The prevalence of DM2 in Spanish adults ranges from 7% to 16%8–11 and the prevalence of CKD in the Spanish diabetic population is within the range of 22%–34.6% depending on the definition criteria adopted and whether patient were from primary care or hospitals.12–15 The progressive ageing of the population, the aforementioned increase in the prevalence of DM (main cause of CKD), as well as the increase in other health problems such as obesity and arterial hypertension, could double the incidence of CKD in the coming decades,16,17 with the subsequent increased in cardiovascular risk and in healthcare costs.

This study was designed with the objective of ascertaining the prevalence of CKD in the diabetic population of Extremadura and comparing its distribution in the region’s different healthcare regions, using, as diagnostic criteria, those proposed in the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcome (KDIGO 2012) guidelines.18

Patients and methodsExtremadura is one of the Autonomous Communities of Spain, with a total population of 1,104,004 inhabitants (548,054 male) in 2013.19 In a 95.3% of the population is the health care is covered by the publicly-funded Health System of Extremadura (SES); and the results of the present study refer to this population. The remaining 4.7% of the population of Extremadura is covered by other healthcare providers. (European Health Interview Survey, 2014).20

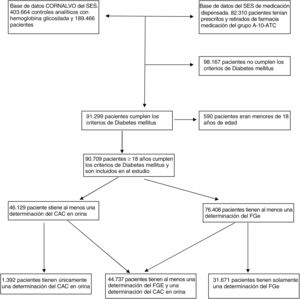

A descriptive prevalence study was conducted with the information collected in 2012, 2013 and 2014, in the clinical analysis (CORNALVO) and medication dispensed databases of the Health System of Extremadura. In this database, patients to whom medication of the A10-ATC group (drugs used in diabetes in the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical classification system) had been prescribed and which had been collected from the pharmacy were identified. In the clinical analysis database, the patients who had had at least one glycosylated haemoglobin determination (HbA1C) in the three-year study period were identified. A patient with diabetes was defined as any patient that had collected medication from the A10-ATC group during the study period and all those who did not collected the medication but had an HbA1C, determination with values ≥6.5%.21

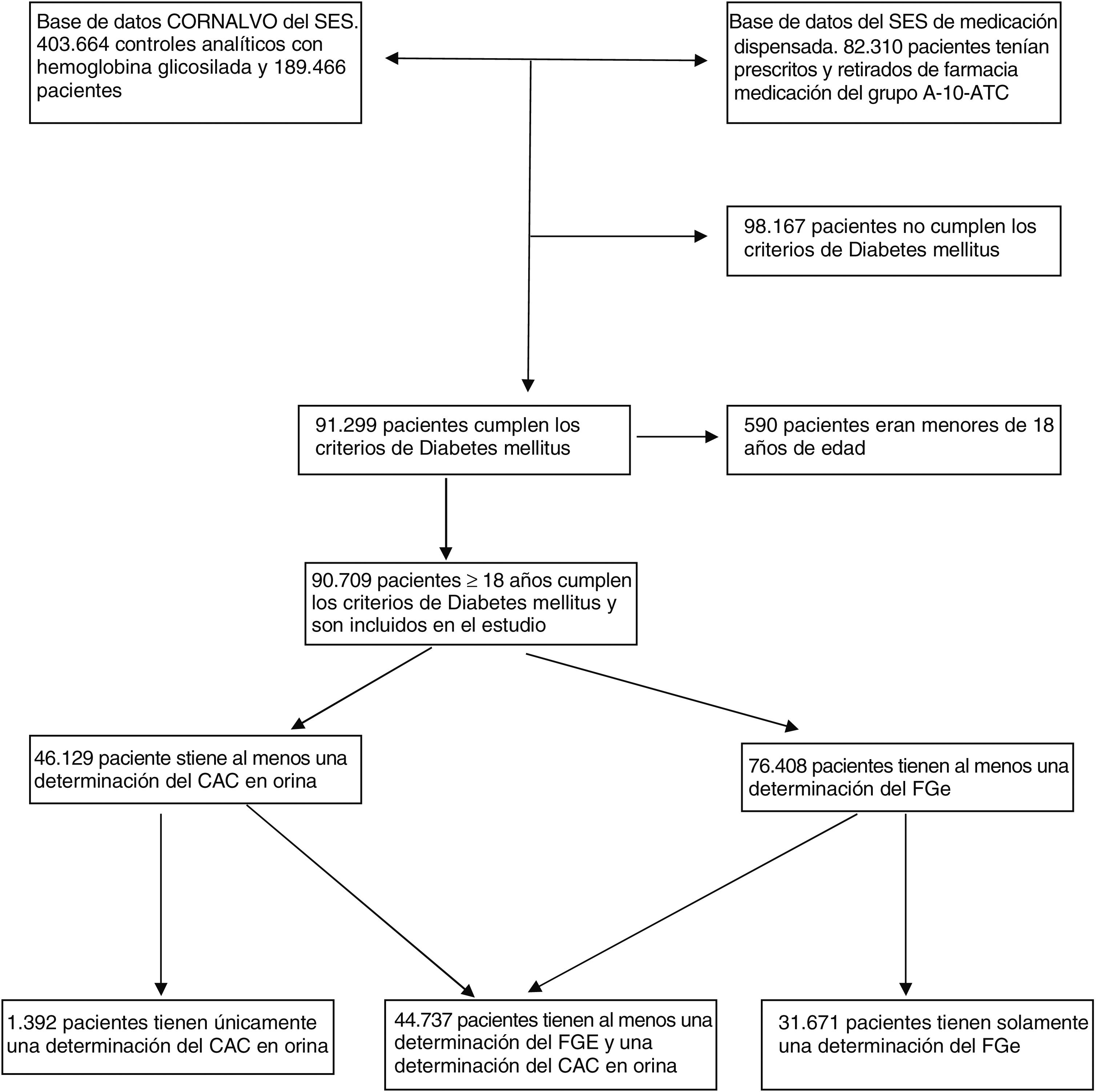

The patients with criteria of diabetes were selected; and 90,709 diabetic patients ≥18 years of age who had had at least one serum creatinine determination (76,408 patients), or at least one creatinine and albumin determination in urine (46,129 patients) were included (Fig. 1).

The estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated using the equation developed by the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI)22 corrected for sex (woman), but not race (black), and the urine albumin/creatinine ratio (uACR) was calculated. A patient with CKD was defined as any patient who, in the latest analysis performed during the study period, presented an eGFR <60mL/min/1.73m2 and/or a uACR ≥30mg/g, confirmed in a previous determination, separated by at least three months.18

The study had the support and the approval of the Management of the Health Service of Extremadura, and since the data source used contained anonymised electronic records, no patient informed consent was required.

The SPSS 22.0 Statistics package for Windows (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used for data processing and analysis.

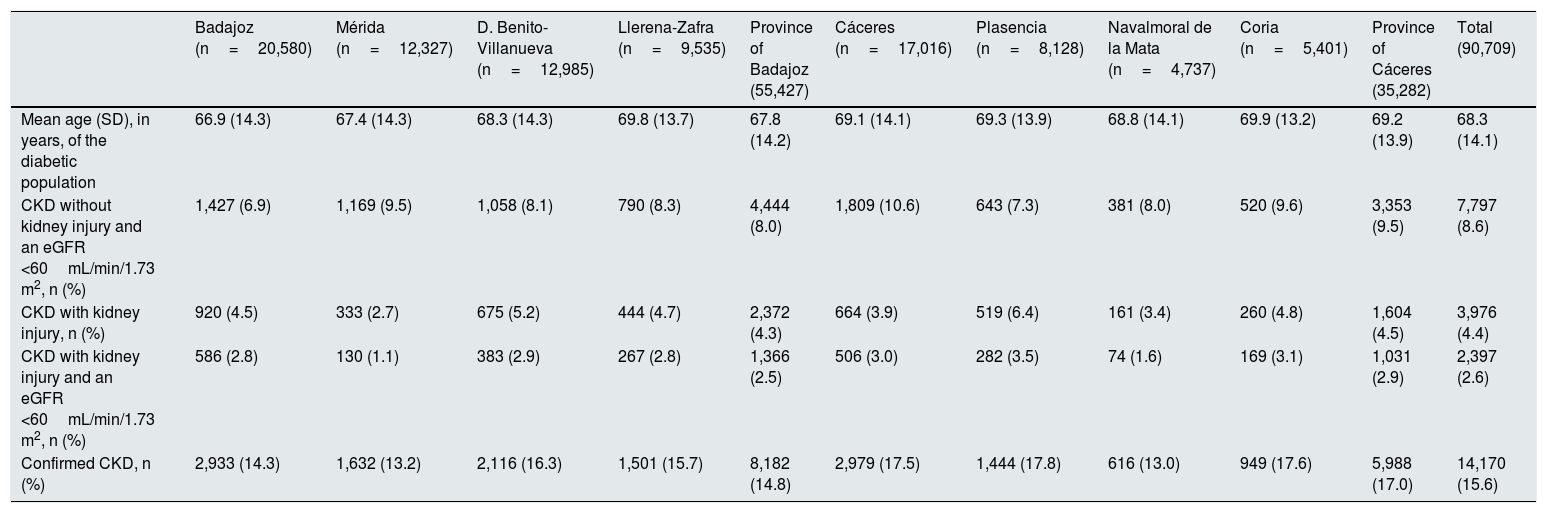

Results90,709 diabetic patients aged ≥18 years (mean age: 68.33±14.12 years; 50.2% women) were included. A total of 14,170 patients (7,797 diabetic patients with eGFR <60mL/min, 3,976 with elevated uACR and 2,397 with both) fulfilled the CKD criteria. Therefore the prevalence of CKD in the diabetic population of Extremadura was 15.6% (Table 1). The prevalence of CKD was higher in the province of Cáceres (17%) than in Badajoz (14.8%, p<0.001) and was also higher in the health area of Cáceres (17.5%) than in the health area of Badajoz (14.3%, p<0.001), with the lowest prevalence of CKD found in the health area of Navalmoral de la Mata (13.0%) and the highest in the health area of Plasencia (17.8%, p<0.001).

Prevalence of chronic kidney disease, kidney injury and diminished glomerular filtration in the diabetic population of the different health areas of Extremadura.

| Badajoz (n=20,580) | Mérida (n=12,327) | D. Benito-Villanueva (n=12,985) | Llerena-Zafra (n=9,535) | Province of Badajoz (55,427) | Cáceres (n=17,016) | Plasencia (n=8,128) | Navalmoral de la Mata (n=4,737) | Coria (n=5,401) | Province of Cáceres (35,282) | Total (90,709) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (SD), in years, of the diabetic population | 66.9 (14.3) | 67.4 (14.3) | 68.3 (14.3) | 69.8 (13.7) | 67.8 (14.2) | 69.1 (14.1) | 69.3 (13.9) | 68.8 (14.1) | 69.9 (13.2) | 69.2 (13.9) | 68.3 (14.1) |

| CKD without kidney injury and an eGFR <60mL/min/1.73 m2, n (%) | 1,427 (6.9) | 1,169 (9.5) | 1,058 (8.1) | 790 (8.3) | 4,444 (8.0) | 1,809 (10.6) | 643 (7.3) | 381 (8.0) | 520 (9.6) | 3,353 (9.5) | 7,797 (8.6) |

| CKD with kidney injury, n (%) | 920 (4.5) | 333 (2.7) | 675 (5.2) | 444 (4.7) | 2,372 (4.3) | 664 (3.9) | 519 (6.4) | 161 (3.4) | 260 (4.8) | 1,604 (4.5) | 3,976 (4.4) |

| CKD with kidney injury and an eGFR <60mL/min/1.73 m2, n (%) | 586 (2.8) | 130 (1.1) | 383 (2.9) | 267 (2.8) | 1,366 (2.5) | 506 (3.0) | 282 (3.5) | 74 (1.6) | 169 (3.1) | 1,031 (2.9) | 2,397 (2.6) |

| Confirmed CKD, n (%) | 2,933 (14.3) | 1,632 (13.2) | 2,116 (16.3) | 1,501 (15.7) | 8,182 (14.8) | 2,979 (17.5) | 1,444 (17.8) | 616 (13.0) | 949 (17.6) | 5,988 (17.0) | 14,170 (15.6) |

SD, standard deviation; CKD, chronic kidney disease; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration by means of the CKD-EPI formula (derived from the equation developed by the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration).

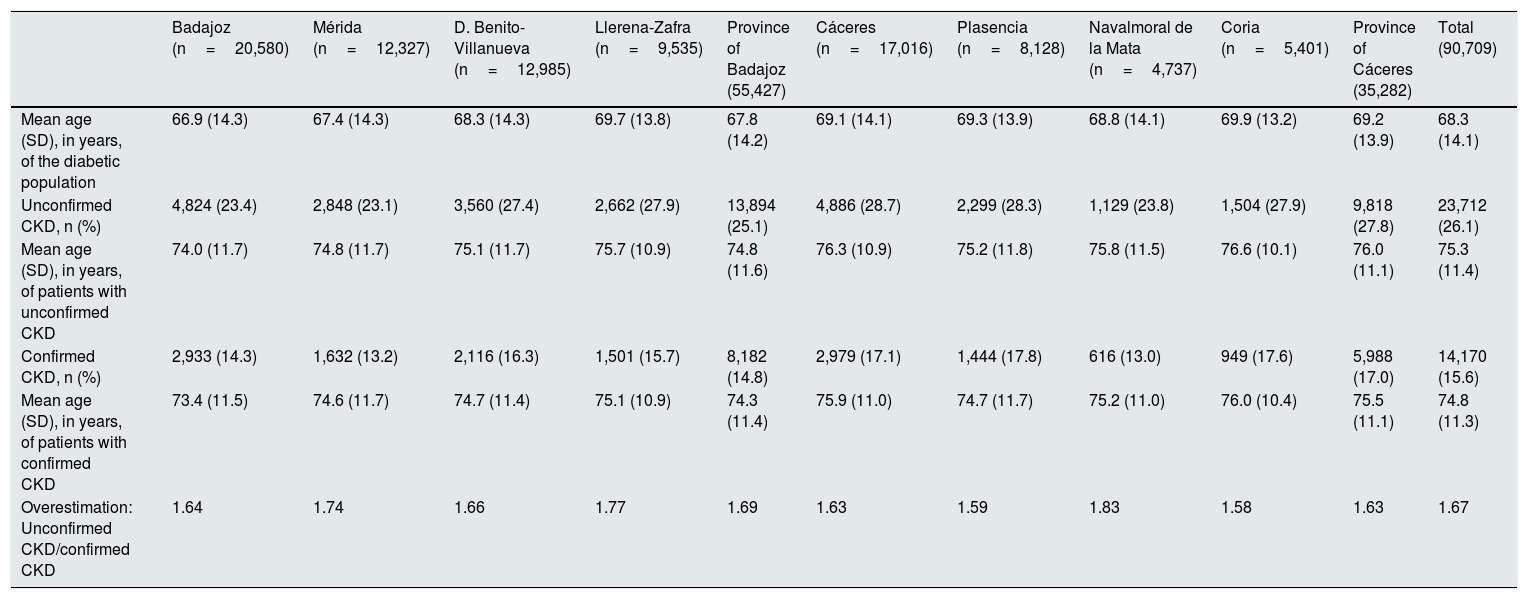

The estimated prevalence of CKD defined without the need for confirmation of the sustainability of the uACR or of the diminished eGFR was 26.1% versus the aforementioned 15.6% of confirmed CKD (Table 2), which involves an overestimation of 67% when the prevalence of CKD is defined with a single isolated value of elevated uACR or eGFR of less than 60mL/min/1.73 m2. The highest overestimation was found in the health area of Navalmoral de la Mata (83%) and the lowest in the area of Coria (58%). The mean age of patients with confirmed CKD was 74.8 years versus the 75.3 of those with unconfirmed CKD (p<0.01).

Prevalence of chronic kidney disease, confirmed and unconfirmed, of the diabetic population in the health areas and provinces of Extremadura.

| Badajoz (n=20,580) | Mérida (n=12,327) | D. Benito-Villanueva (n=12,985) | Llerena-Zafra (n=9,535) | Province of Badajoz (55,427) | Cáceres (n=17,016) | Plasencia (n=8,128) | Navalmoral de la Mata (n=4,737) | Coria (n=5,401) | Province of Cáceres (35,282) | Total (90,709) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (SD), in years, of the diabetic population | 66.9 (14.3) | 67.4 (14.3) | 68.3 (14.3) | 69.7 (13.8) | 67.8 (14.2) | 69.1 (14.1) | 69.3 (13.9) | 68.8 (14.1) | 69.9 (13.2) | 69.2 (13.9) | 68.3 (14.1) |

| Unconfirmed CKD, n (%) | 4,824 (23.4) | 2,848 (23.1) | 3,560 (27.4) | 2,662 (27.9) | 13,894 (25.1) | 4,886 (28.7) | 2,299 (28.3) | 1,129 (23.8) | 1,504 (27.9) | 9,818 (27.8) | 23,712 (26.1) |

| Mean age (SD), in years, of patients with unconfirmed CKD | 74.0 (11.7) | 74.8 (11.7) | 75.1 (11.7) | 75.7 (10.9) | 74.8 (11.6) | 76.3 (10.9) | 75.2 (11.8) | 75.8 (11.5) | 76.6 (10.1) | 76.0 (11.1) | 75.3 (11.4) |

| Confirmed CKD, n (%) | 2,933 (14.3) | 1,632 (13.2) | 2,116 (16.3) | 1,501 (15.7) | 8,182 (14.8) | 2,979 (17.1) | 1,444 (17.8) | 616 (13.0) | 949 (17.6) | 5,988 (17.0) | 14,170 (15.6) |

| Mean age (SD), in years, of patients with confirmed CKD | 73.4 (11.5) | 74.6 (11.7) | 74.7 (11.4) | 75.1 (10.9) | 74.3 (11.4) | 75.9 (11.0) | 74.7 (11.7) | 75.2 (11.0) | 76.0 (10.4) | 75.5 (11.1) | 74.8 (11.3) |

| Overestimation: Unconfirmed CKD/confirmed CKD | 1.64 | 1.74 | 1.66 | 1.77 | 1.69 | 1.63 | 1.59 | 1.83 | 1.58 | 1.63 | 1.67 |

SD, standard deviation; CKD, chronic kidney disease; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration by means of the CKD-EPI formula (derived from the equation developed by the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration).

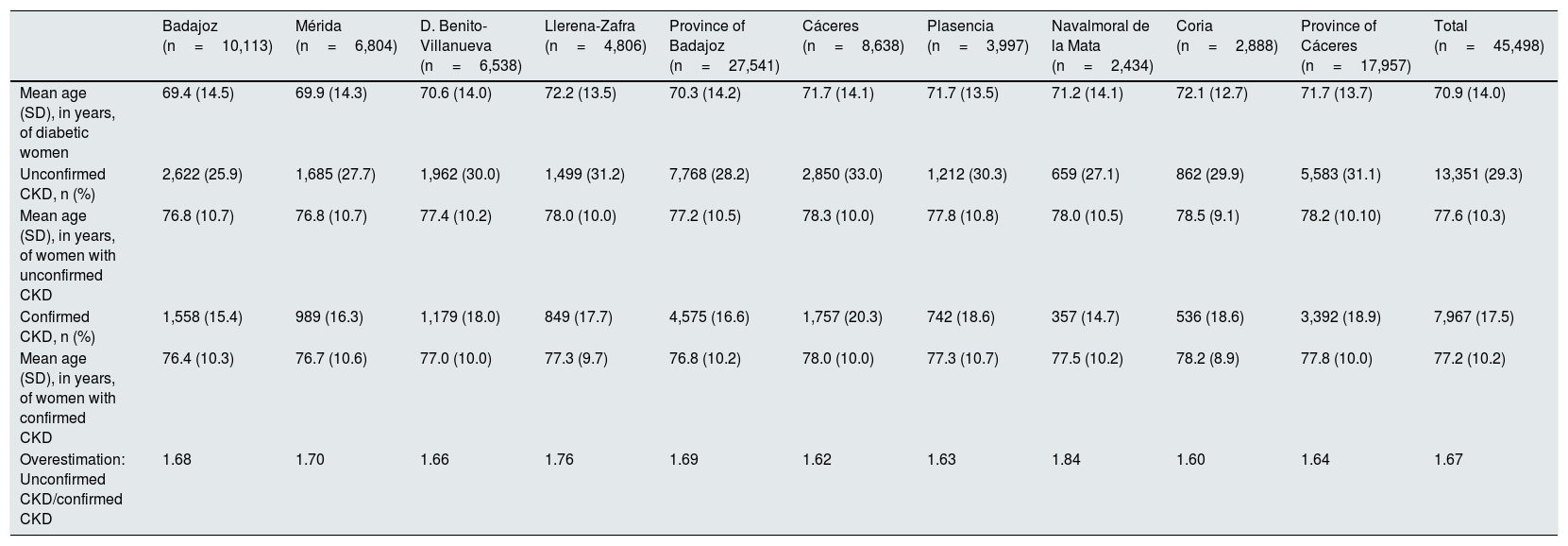

The comparison of the prevalence of CKD in diabetic women by health areas, estimated with and without confirmation of kidney injury or of reduced eGFR, is displayed in Table 3, with a prevalence of confirmed CKD of 17.5% versus 29.3% of unconfirmed CKD (p<0.001), with the highest prevalence of confirmed CKD in the health area of Cáceres (20.34%) and the lowest in the health area of Navalmoral de la Mata (14.7%, p<0.001), which was also the health area with the highest overestimation of CKD prevalence (84%). The mean age of women with confirmed and unconfirmed CKD was 77.2 and 77.6 years, respectively (p<0.05).

Prevalence of chronic kidney disease, confirmed and unconfirmed, of diabetic women in the health areas and provinces of Extremadura.

| Badajoz (n=10,113) | Mérida (n=6,804) | D. Benito-Villanueva (n=6,538) | Llerena-Zafra (n=4,806) | Province of Badajoz (n=27,541) | Cáceres (n=8,638) | Plasencia (n=3,997) | Navalmoral de la Mata (n=2,434) | Coria (n=2,888) | Province of Cáceres (n=17,957) | Total (n=45,498) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (SD), in years, of diabetic women | 69.4 (14.5) | 69.9 (14.3) | 70.6 (14.0) | 72.2 (13.5) | 70.3 (14.2) | 71.7 (14.1) | 71.7 (13.5) | 71.2 (14.1) | 72.1 (12.7) | 71.7 (13.7) | 70.9 (14.0) |

| Unconfirmed CKD, n (%) | 2,622 (25.9) | 1,685 (27.7) | 1,962 (30.0) | 1,499 (31.2) | 7,768 (28.2) | 2,850 (33.0) | 1,212 (30.3) | 659 (27.1) | 862 (29.9) | 5,583 (31.1) | 13,351 (29.3) |

| Mean age (SD), in years, of women with unconfirmed CKD | 76.8 (10.7) | 76.8 (10.7) | 77.4 (10.2) | 78.0 (10.0) | 77.2 (10.5) | 78.3 (10.0) | 77.8 (10.8) | 78.0 (10.5) | 78.5 (9.1) | 78.2 (10.10) | 77.6 (10.3) |

| Confirmed CKD, n (%) | 1,558 (15.4) | 989 (16.3) | 1,179 (18.0) | 849 (17.7) | 4,575 (16.6) | 1,757 (20.3) | 742 (18.6) | 357 (14.7) | 536 (18.6) | 3,392 (18.9) | 7,967 (17.5) |

| Mean age (SD), in years, of women with confirmed CKD | 76.4 (10.3) | 76.7 (10.6) | 77.0 (10.0) | 77.3 (9.7) | 76.8 (10.2) | 78.0 (10.0) | 77.3 (10.7) | 77.5 (10.2) | 78.2 (8.9) | 77.8 (10.0) | 77.2 (10.2) |

| Overestimation: Unconfirmed CKD/confirmed CKD | 1.68 | 1.70 | 1.66 | 1.76 | 1.69 | 1.62 | 1.63 | 1.84 | 1.60 | 1.64 | 1.67 |

SD, standard deviation; CKD, chronic kidney disease.

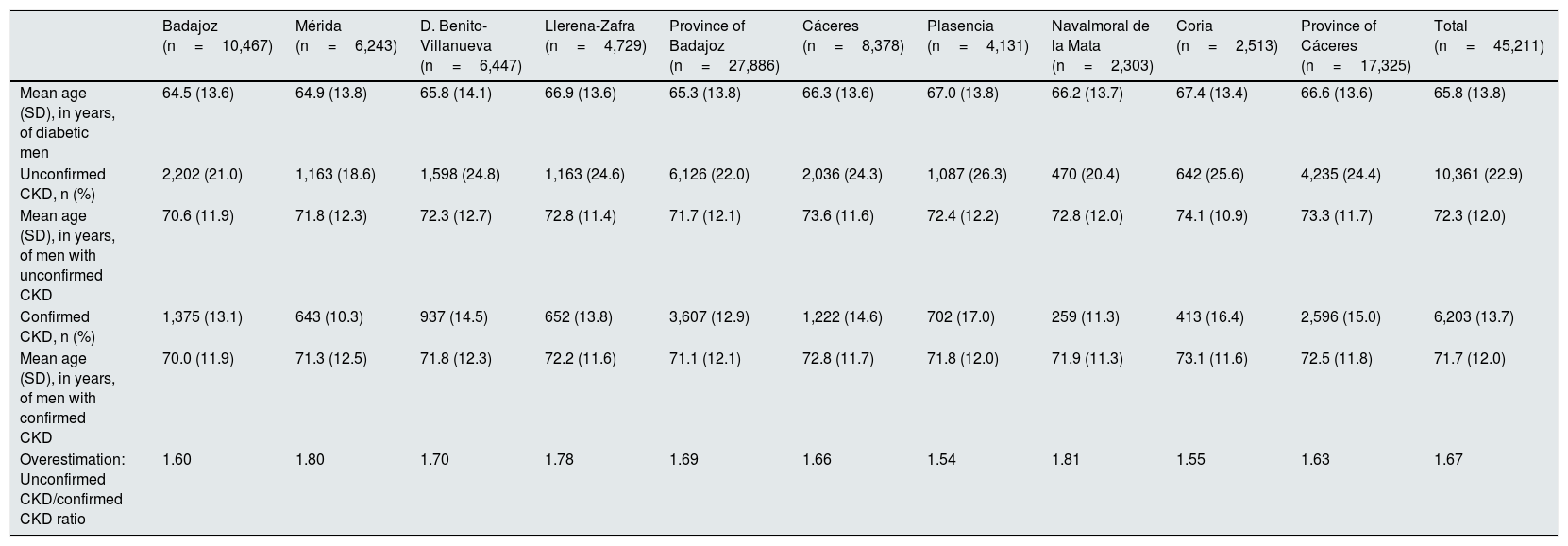

Table 4 compares the prevalences of CKD in males, the prevalence of confirmed CKD was 13.7% versus 22.9% of unconfirmed CKD (p<0.001), which also involves an overestimation of 67%, with the highest overestimation of prevalence corresponding to the health area of Navalmoral de la Mata (81%) and the lowest to the health area of Plasencia (54%). The mean age of males with confirmed CKD was 71.7 years versus the 72.3 of those with unconfirmed CKD (p<0.01).

Prevalence of chronic kidney disease, confirmed and unconfirmed, of diabetic men, in the health areas and provinces of Extremadura.

| Badajoz (n=10,467) | Mérida (n=6,243) | D. Benito-Villanueva (n=6,447) | Llerena-Zafra (n=4,729) | Province of Badajoz (n=27,886) | Cáceres (n=8,378) | Plasencia (n=4,131) | Navalmoral de la Mata (n=2,303) | Coria (n=2,513) | Province of Cáceres (n=17,325) | Total (n=45,211) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (SD), in years, of diabetic men | 64.5 (13.6) | 64.9 (13.8) | 65.8 (14.1) | 66.9 (13.6) | 65.3 (13.8) | 66.3 (13.6) | 67.0 (13.8) | 66.2 (13.7) | 67.4 (13.4) | 66.6 (13.6) | 65.8 (13.8) |

| Unconfirmed CKD, n (%) | 2,202 (21.0) | 1,163 (18.6) | 1,598 (24.8) | 1,163 (24.6) | 6,126 (22.0) | 2,036 (24.3) | 1,087 (26.3) | 470 (20.4) | 642 (25.6) | 4,235 (24.4) | 10,361 (22.9) |

| Mean age (SD), in years, of men with unconfirmed CKD | 70.6 (11.9) | 71.8 (12.3) | 72.3 (12.7) | 72.8 (11.4) | 71.7 (12.1) | 73.6 (11.6) | 72.4 (12.2) | 72.8 (12.0) | 74.1 (10.9) | 73.3 (11.7) | 72.3 (12.0) |

| Confirmed CKD, n (%) | 1,375 (13.1) | 643 (10.3) | 937 (14.5) | 652 (13.8) | 3,607 (12.9) | 1,222 (14.6) | 702 (17.0) | 259 (11.3) | 413 (16.4) | 2,596 (15.0) | 6,203 (13.7) |

| Mean age (SD), in years, of men with confirmed CKD | 70.0 (11.9) | 71.3 (12.5) | 71.8 (12.3) | 72.2 (11.6) | 71.1 (12.1) | 72.8 (11.7) | 71.8 (12.0) | 71.9 (11.3) | 73.1 (11.6) | 72.5 (11.8) | 71.7 (12.0) |

| Overestimation: Unconfirmed CKD/confirmed CKD ratio | 1.60 | 1.80 | 1.70 | 1.78 | 1.69 | 1.66 | 1.54 | 1.81 | 1.55 | 1.63 | 1.67 |

SD, standard deviation; CKD, chronic kidney disease.

The estimated prevalence of CKD in the databases of the diabetic population of Extremadura ≥18 years is 15.6%, with significant differences between the eight health areas of the region. The highest prevalence corresponded to the health area of Plasencia (17.8%) and the lowest to the health area of Navalmoral de la Mata (13%). If the estimation of prevalence were performed defining CKD without a need for the confirmation of the sustainability of the eGFR or kidney injury over time, the prevalence would have been 26.1%, which constitutes an overestimation of 67%.

Strong points and limitations of this studyThe strong points the study are that it is an analyses the information pertaining to the diabetic population in practically the entire population of Extremadura (95%) and that it uses, as diagnostic for CKD, the criteria recommended by the National Kidney Foundation K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification,18 which require the confirmation of reduced eGFR or the presence of kidney injury in two determinations separated by at least three months. However, this study also has limitations. The patients with diabetes were identified with diagnostic criteria based on whether they took glucose-lowering agents and haemoglobin A1C and not by a review of the patients’ medical history.11 This strategy has the advantage of identifying many patients with unknown diabetes, although it has the drawback of including as diabetics a small number of patients that might have a chronic prescription of antidiabetic agents for an indication other than diabetes, for example polycystic ovary syndrome (metformin), obesity (metformin and incretin analogues) or gestational diabetes (metformin, insulin).11 In addition, we did not know the number of diabetic patients that have had a kidney transplantation and who should have been excluded from the analysis, although the number of these patients should not be significant relative to the total number of 90,709 diabetics patients included.

Comparison with the existing literatureThe mean prevalence of CKD in the diabetic population of Extremadura in our study (15.6%; ranging in the eight health areas from 13% to 17.8%) is below the prevalence estimated (20.3%) in other studies of our region,23 as well as the range of prevalences (23%–27.9%) found in Spain.12,13,15

However, in all these studies, CKD is defined with a single determination of eGFR without fulfilling the recommended criteria that the reduction in eGFR or the increase in the uACR must be confirmed in another determination separated by at least three months.18 The prevalence of CKD in our study is also below the 20%–40% bracket of prevalence of CKD in the diabetic population of other countries, although in these cases the prevalence of CKD is usually estimated with a single determination of eGFR.1,5,6 This procedure of estimating the prevalence of CKD accounts, at least partially, for the lower prevalence of CKD in the diabetic population of our study, although it is possibly closer to the real prevalence, since a single value of reduced eGFR or manifestation of kidney injury may correspond to transient situations and not to chronic functional alterations as required by the definition of CKD.18 In fact, if in our study we did not require a confirmation of kidney injury or of diminished eGFR, as in the aforementioned studies,1,5,6,12,13,15,16,23 the prevalence of CKD would have been 26.1% (which would be an overestimation of 67%), with a range of prevalences in the eight health areas that would go from 23.1% in the health area of Mérida to 28.7% in the health area of Cáceres, in the range of prevalence of the studies conducted in Spain.12,13,15

Other results of our study, such as the greater age of the diabetic patients with CKD and the greater prevalence of CKD in women, concur with the literature,1,4,12,13,24,25 which points to age and female sex as CKD risk factors. CKD is the ninth main cause of death (1.8% of deaths) in women in the USA, but is not among the 10 main causes of death among men.26 In the general population, the prevalence of CKD is also higher in women (11.8%) than in men (10.4%),27 although CKD could be overestimated in women, partly by applying the same body surface for both sexes in renal function equations.28

Finally, it should be pointed out that in the three-year period of analysis, only 85.8% of the diabetic population had a serum creatinine determination that made it possible to calculate the eGFR and only 50.8% had a determination of uACR. We do not know the reasons why 14.2% and 49.2%, respectively, did not have these determinations, when the recommendations of the clinical guidelines are that they should be performed at least once a year.25

Implications for future research and for clinical practiceIn summary, our study reveals a prevalence of 15.6% of CKD in the diabetic population of Extremadura (Spain), accepting the criteria defined in the National Kidney Foundation K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines. But the high percentage (49.2%) of patients without uACR determinations and also (14.2%) without an estimation of GFR renders it necessary to review the quality of care provided to patients with diabetes in Extremadura.

Ethical declarationsThe authors declare that they have fulfilled the protocols of the work centre and that this article does not contain patient data.

FundingNo funding was received for this work.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

To Dr Luis Tobajas Belvís, Director General of Health Planning, Training and Social and Social and Health Quality of the Department of Health and Social Policies of the Autonomous Government of Extremadura; to Dr Luis Lozano Mera, Project Manager of the Healthcare-Primary Care System of the Health Service of Extremadura (SES); and to Dr Vicente Alonso Núñez, Director General of Healthcare of the SES, for their invaluable cooperation in authorising and facilitating the databases.