In recent years, there has been a gradual increase in the number of patients in Spain's home haemodialysis (HHD) programme.1 In spite of this, there are difficulties involved in increasing implementation of the technique.2,3 Therefore, it seems fitting for us to present our experience with the use of an HHD nursing support (HHDN) programme to care for patients at home while haemodialysis (HD) sessions are being carried out. We analysed the reasons for these visits and whether the use of this programme is beneficial for the survival of the HHD technique. The programme was financed by the Asociación de Lucha contra Enfermedades Renales de Castellón (Castellón Association for the Fight against Kidney Diseases — ALCER-Castalia).

From the start of the HHDN programme on 01/07/2017 to 01/03/2020, 402 home visits were made to the 39 patients who received HHD during this period (13 prevalent and 26 incident cases with regard to the HHD technique), with 21,152 cumulative days of patient follow-up and 57.95 patient-years of follow-up.

The mean age of the patients was 52.9 ± 12.3 years, 25 were male (64.1%) and 14 female (35.9%), 12 had diabetes mellitus (30.8%), with a Charlson comorbidity index of 5.2 ± 2.1. Eighteen conventional monitors adapted for the HHD technique (46.2%) and 21 portable monitors (53.8%) were used. Nine patients had an arteriovenous fistula as initial vascular access (23.1%), while 30 had catheters (76.9%). Patients' education levels were: 16 with basic education (41%), 20 further education (51.3%) and three higher education (7.7%). Twelve of the 31 working-age patients were in work (38.7%). At the end of the period, 23 patients (59%) continued in the HHD programme, while the reasons for discontinuation of the technique were: three deaths (7.7%), nine transplants (23.1%) and four centre transfers (10.2%).

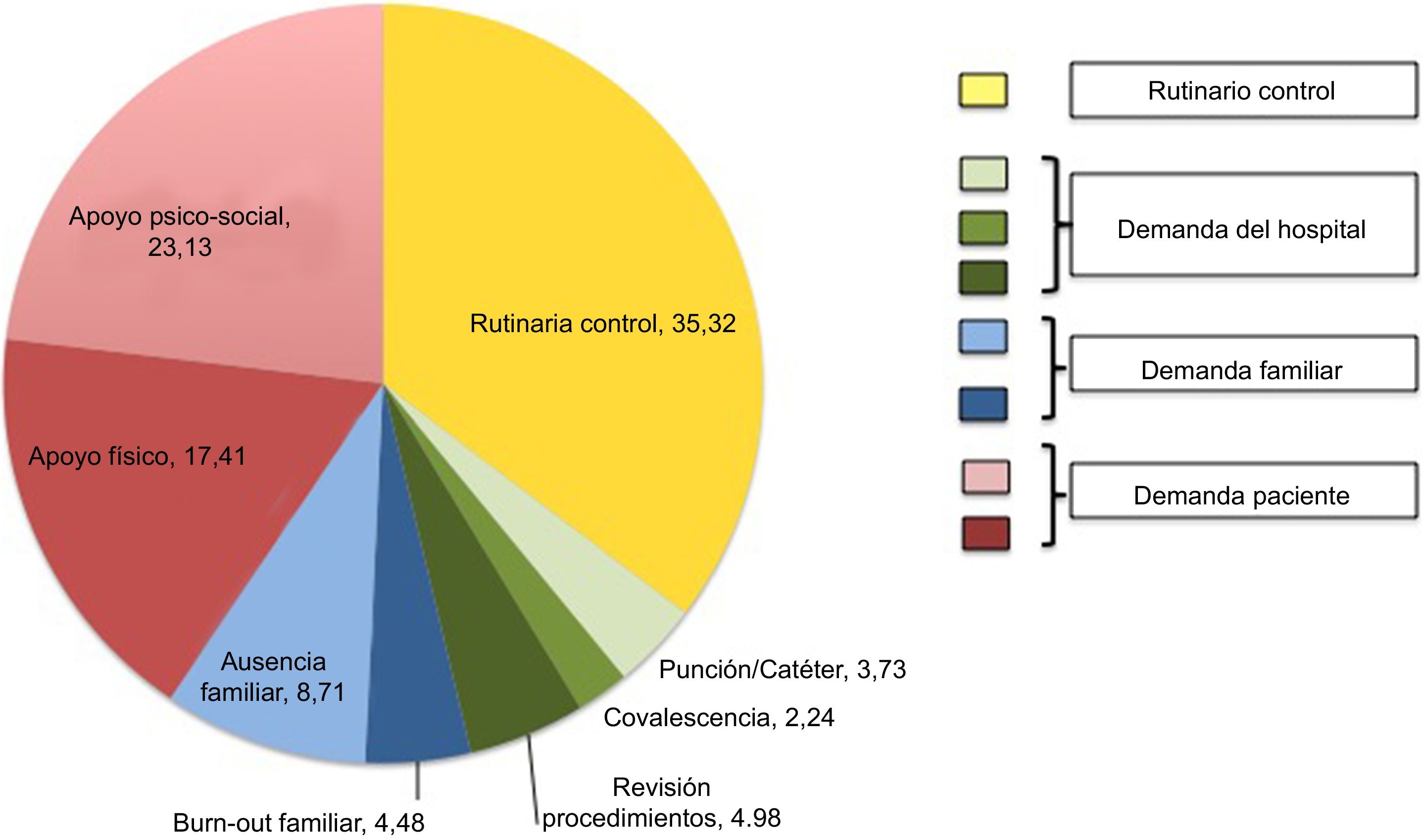

The motives for the home visits are described in Fig. 1.

Out of all the patients, nine refused to receive HHDN visits, 14 received a single visit, seven patients received 2–10 visits and nine patients received more than 10 visits; this last group accounted for 90.8% of the visits. There was no statistically significant relationship between the need for HHDN support and age, Charlson index, distance, education level, employment, the vascular access used or the type of monitor.

In total, the nurse travelled 10,541 km, working for 1758.36 hours over 32 months (54.95 hours per month).

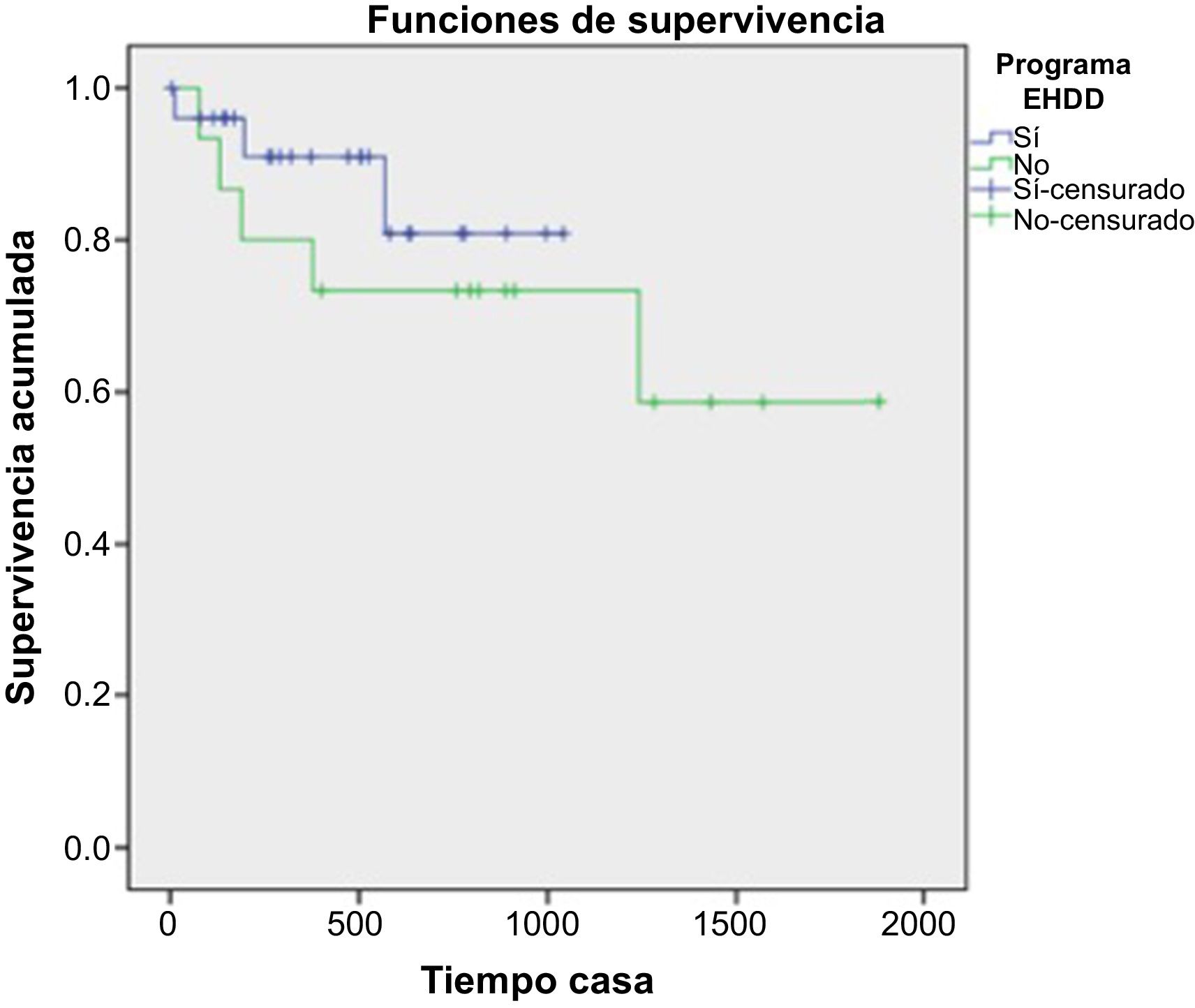

We compared technique survival using the Kaplan–Meier method (censoring death and transplant) between the 26 incident patients, who always had the option of accessing HHDN with 15 historic patients from our unit prior to the operation of the HHDN programme (Fig. 2). The groups were comparable in terms of age and Charlson index, with a technique survival in the group with access to HHDN of 96% at six months, 90.9% at one year and 80.8% at two years, versus 86.7% at six months, 80% at one year and 73.3% at two years for the group without access to HHDN; these differences did not reach statistical significance (log rank = 0.418).

The HHDN programme saved patients from making unnecessary trips to the hospital, generating economic savings that can be determined by the difference in cost between HD sessions in hospital and at home, and that would enable a sufficient number of patients to self-finance for a single payer.

Although the HHDN programme was not able to increase the statistical significance of the technique survival of HHD patients, the trend was positive, with the most evident improvement in the first year, which is when most technique failures occur in HHD,4 and would therefore be the key moment for home support, with the difference lessening at two years.

A large part of the HHDN requests were for psychosocial support or were family requests, as has occurred in other studies exploring the reasons for technique failure,5 enabling us to act on the barriers that make it difficult to maintain patients on HHD6 and in particular meeting the needs of patients’ caregivers.7 The nine patients who made up 90.8% of the visits would not have been maintained on HHD without HHDN. Routine visits also enabled us to detect failings in patient management of the technique early, and thus to get ahead of possible complications.

Home dialysis nursing support programmes have been successfully implemented in other countries such as Canada, extending the possibility of choosing the HHD technique,8 and France, increasing patient survival and quality of life.9 In our case, nursing support was provided to patients on a one-off basis and not continually, as in other described experiences in HHD,10 although it is evident that a small number of patients accounted for the bulk of the resource.

We conclude that the implementation of HHDN programmes can entail a benefit in the implementation of HHD, helping to overcome barriers, especially patient- and family-dependent barriers, without evident economic overspend, and makes it possible to increase both the number of patients on HHD and maintenance of the technique over time.

Conflicts of interestDr Pérez Alba declares having received fees for presentations on home haemodialysis from Baxter. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Pérez-Alba A, Catalán Navarrete S, Renau Ortells E, García Peris B, Agustina Trilles A, Cerrillo García V, Calvo Gordo C. Programa de enfermería de apoyo a hemodiálisis domiciliaria. Experiencia de un centro. Nefrologia. 2021;41:360–362.