People with a reduced nighttime dip in blood pressure have an increased cardiovascular risk. Our objective was to describe the different patterns in blood pressure (BP) among pediatricians who work in long on-duty shifts in relation with sex, medical rank and sleeping time.

MethodsDescriptive, cross-sectional, two-center study. On duty pediatric Resident physicians and pediatric Consultants were recruited between January 2018 and December 2021.

ResultsFifty-one physicians were included in the study (78.4% female, 66.7% Resident physicians). Resident physicians had a higher night/day ratio (0.91 vs 0.85; p<0.001) and a shorter nighttime period (3.87 vs 5.41, p<0.001) than Consultants. Physicians sleeping less than 5h had a higher night/day ratio (0.91 vs 0.87, p=0.014). Being a Resident showed a ∼4.5-fold increased risk of having a non-dipping BP pattern compared to Consultants.

ConclusionWe found a potential link between both being a Resident and, probably, having shorter sleeping time, and the non-dipping BP pattern in physicians during prolonged shifts.

Las personas con un descenso nocturno reducido de la presión arterial tienen mayor riesgo cardiovascular. Nuestro objetivo fue describir los diferentes patrones de presión arterial en los pediatras que trabajan de guardia con presencia física, en relación con el sexo, la categoría profesional y el tiempo de sueño.

MétodosSe realizó un estudio descriptivo, transversal, bicéntrico. Se reclutó a médicos residentes y adjuntos de pediatría, de guardia con presencia física, entre enero de 2018 y diciembre de 2021.

ResultadosFueron incluidos en el estudio 51 médicos (78,4% mujeres; 66,7% médicos residentes). Los médicos residentes presentaron un cociente de presión arterial noche/día mayor (0,91 vs. 0,85; p<0,001) y un tiempo de sueño menor (3,87 vs. 5,41; p<0,001) que los adjuntos. Los participantes que durmieron menos de 5horas presentaron un cociente de presión arterial noche/día mayor (0,91 vs. 0,87; p=0,014). Ser médico residente demostró tener aumentado el riesgo de presentar un patrón no dipper en más de 4,5 veces respecto a los médicos adjuntos.

ConclusionesEncontramos un vínculo potencial entre ser médico residente y, probablemente, tener menos horas de sueño, y el patrón de no descenso nocturno de la presión arterial en los médicos durante las guardias de presencia física.

Hypertension (HTN) is a major preventable cause of cardiovascular diseases and all-cause mortality worldwide, with an overall prevalence of 30–45%.1 There is growing evidence suggesting that shift work is a risk factor for many negative health outcomes, including cardiovascular disease and HTN.2–4 Also, there is evidence noting an association between shift work and sleep deprivation, and between sleep deprivation and HTN.5–7

So far, most studies about shift work classified HTN based on office blood pressure (BP) measurement.4 However, ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) techniques have expanded the knowledge regarding the circadian rhythm of BP and now, ABPM is considered as the gold standard method for evaluating BP, providing a more accurate estimation of BP related risks.8,9 People with a reduced nighttime dip in BP (<10% of the daytime average BP or a night/day ratio>0.9) have an increased cardiovascular risk.10,11

The main objective of the study was to describe the different patterns in BP among pediatricians who work in long on-duty shifts in relation with sex, medical rank (resident physicians vs consultants) and sleeping time.

MethodsStudy designWe conducted a descriptive, cross-sectional, two-center study. On duty pediatric Resident physicians and pediatric Consultants working in two hospitals were recruited between January 2018 and December 2021. One center was a tertiary teaching hospital and the other one was a secondary teaching hospital, both in Spain. Physicians with conditions that may affect their fluid and electrolyte balance (impaired kidney function, pregnancy, diabetes, hypertension) and those who refused to participate in the study were excluded. Weight and height were measured for each subject and total body surface (TBS) and body mass index (BMI) were calculated. Sex, age and relevant past medical history was collected for each subject. During the 17-h shift, hours of activity, hours of rest and ABPM were recorded. Each participant documented the hours of active work and the hours of sleep during the shift.

BP measurement was carried out following the recommendations of the European Society of Hypertension.10 Basal systolic BP (SBP) and diastolic BP (DBP) were measured at the office with a validated automatic oscillometric device (SunTech CT40, SunTech Medical Inc., Morrisvilles, NC, USA), after 5-min rest in a sitting position. BP values were estimated as the mean of two readings. Thereafter, 17-h ABPM was performed using the SpaceLabs 90207 automated non-invasive oscillometric device (Spacelabs Medical, Space-Labs Inc., Redmond, WA, USA), programmed to register BP every 30-min from 11 pm to 7 am and every 20-min the rest of the time. We selected cuff size to fit the individual's arm circumference according to the device's instructions. Pediatricians were instructed to maintain their usual activities on duty, return the following morning for device removal and keep the arm extended and immobile at the time of each cuff inflation, if it was possible. Valid registries had to fulfill a series of pre-established criteria, including 80% of systolic BPs and diastolic BPs successful recordings during the daytime and nighttime periods, 17-h duration, and at least one BP measurement per hour. Daytime and nighttime periods were defined individually according to the hours of active work and sleep, respectively.

Definitions- -

Night/day ratio: ratio of average nighttime BP to average daytime BP for SBP and DBP separately.

- -

Definition of Circadian Patterns: ≥10% reduction in the average SBP during the nighttime period compared to daytime mean SBP was considered normal dipping pattern (dipper). Contrariwise, a <10% reduction of mean nighttime SBP compared to daytime mean SBP was considered abnormal dipping pattern (non-dipper).

Statistical analysis was carried out using the R program (R Development Core Team), version 3.6.3. Descriptive analysis was performed providing relative and absolute frequency distributions for qualitative variables, and measures of position and dispersion for the quantitatives. Normally distributed data were expressed as mean±SD, non-normally distributed data as median and interquartile range and categorical variables were reported as percentages. Differences according to sex, medical rank and hours of sleep, grouped into two categories, were assessed with the Student's t test or Wilcoxon for independent samples, after verification of the normality hypothesis. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression models were built to determine the dipping BP pattern profile. A p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

We obtained approval from the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Autonomous Region of Asturias. All persons gave their written informed consent prior to their inclusion in the study.

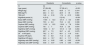

ResultsFifty-one physicians were included in the study (mean age 31±7.5 years old). Forty (78.4%) were female, 34 were resident physicians (66.7%). Mean of BMI was 22.3±2.2. All ABPM records were valid. Description of the population according to sex appears in Table 1.

Characteristics of population according to sex. Tables shows means±SD or median (p25–p75) according to the test used for comparison.

| Male | Female | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 11 | 40 | – |

| Age (years) | 29 (27.5–40.5) | 28 (26–30) | 0.206 |

| Weight (kg) | 71.2±7.1 | 58.5±7.1 | <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.1±2.4 | 22.2±2.2 | 0.227 |

| TBS (m2) | 1.86±0.1 | 1.62±0.12 | <0.001 |

| Nighttime period (h) | 5 (5–5) | 4 (3–5) | 0.076 |

| Basal SBP (mmHg) | 125.2±6.6 | 117.9±12 | 0.013 |

| Basal DBP (mmHg) | 76.3±7.1 | 74.4±7.9 | 0.469 |

| Daytime SBP (mmHg) | 125.4±8.4 | 114.2±8.7 | <0.001 |

| Daytime DBP (mmHg) | 77.9±6.9 | 75.5±5.8 | 0.249 |

| Nighttime SBP (mmHg) | 109.2±12.1 | 103.1±8.6 | 0.063 |

| Nighttime DBP (mmHg) | 60.6±7.3 | 62±6.6 | 0.554 |

| 24h HR (bpm) | 66.9±13.8 | 75.7±8.5 | 0.066 |

| Daytime HR (bpm) | 68.9±14.3 | 77.8±8.5 | 0.073 |

| Nighttime HR (bpm) | 56±11.4 | 65.1±10.4 | 0.016 |

| Night/day ratio SBP (mmHg) | 0.87±0.07 | 0.9±0.05 | 0.095 |

| Night/day ratio DBP (mmHg) | 0.77±0.07 | 0.82±0.07 | 0.044 |

BMI: body mass index; bpm: beats per minute; DBP: diastolic blood pressure; HR: heart rate; mmHg: millimeters of mercury; SBP: systolic blood pressure; TBS: total body surface.

Resident physicians had a higher night/day ratio (0.91±0.05 vs 0.85±0.05; p<0.001) and a shorter nighttime period (3.87±1.36h vs 5.41±1.23h, p<0.001) than Consultants. Description of the population according to medical rank appears in Table 2, while Table 3 describes the population according to hours of sleep. Physicians who sleep less than 5h had a higher night/day ratio (0.91±0.04 vs 0.87±0.07, p=0.014).

Characteristics of population according to medical rank. Tables shows means±SD or median (p25–p75) according to the test used for comparison.

| Residents | Consultants | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 34 | 17 | – |

| Age (years) | 27 (26–28) | 37 (32–41) | <0.001 |

| Weight (kg) | 60.1±9.2 | 63.6±7.7 | 0.314 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.4±2.4 | 22.5±1.9 | 0.951 |

| TBS (m2) | 1.65±0.16 | 1.72±0.13 | 0.269 |

| Nighttime period (h) | 4 (3–5) | 5 (5–6) | <0.001 |

| Basal SBP (mmHg) | 118.6±12.3 | 121.4±9.3 | 0.409 |

| Basal DBP (mmHg) | 75.5±8.3 | 73.3±6.3 | 0.339 |

| Daytime SBP (mmHg) | 115.5±10.5 | 118.8±7.8 | 0.254 |

| Daytime DBP (mmHg) | 76.1±7 | 75.9±3.6 | 0.875 |

| Nighttime SBP (mmHg) | 105.6±9.7 | 101.9±9.5 | 0.204 |

| Nighttime DBP (mmHg) | 62.7±7.5 | 59.7±4.3 | 0.075 |

| 24h HR (bpm) | 76.2±8.7 | 69.1±11.9 | 0.02 |

| Daytime HR (bpm) | 78.1±8.9 | 71.3±2.3 | 0.029 |

| Nighttime HR (bpm) | 64.6±10.7 | 60.1±11.7 | 0.18 |

| Night/day ratio SBP (mmHg) | 0.91±0.05 | 0.85±0.05 | <0.001 |

| Night/day ratio DBP (mmHg) | 0.83±0.07 | 0.78±0.05 | 0.031 |

BMI: body mass index; bpm: beats per minute; DBP: diastolic blood pressure; HR: heart rate; mmHg: millimeters of mercury; SBP: systolic blood pressure; TBS: total body surface.

Characteristics of population according to hours of sleep. Tables shows means±SD or median (p25–p75) according to the test used for comparison.

| <5h of sleep | >5h of sleep | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 23 | 28 | – |

| Residents (N) | 21 | 13 | – |

| Consultants (N) | 2 | 15 | – |

| Age (years) | 28 (26–29) | 29.5 (27–39) | 0.003 |

| Weight (kg) | 59.3±7.5 | 62.8±9.6 | 0.165 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.4±1.7 | 22.3±2.5 | 0.887 |

| TBS (m2) | 1.64±0.15 | 1.70±0.16 | 0.196 |

| Basal SBP (mmHg) | 120.2±13 | 118.9±10 | 0.679 |

| Basal DBP (mmHg) | 76.5±8.8 | 73.4±6.5 | 0.147 |

| Daytime SBP (mmHg) | 116.1±10.4 | 117±9.3 | 0.733 |

| Daytime DBP (mmHg) | 76.4±7.3 | 75.7±4.8 | 0.721 |

| Nighttime SBP (mmHg) | 106.4±10.1 | 102.7±9.1 | 0.184 |

| Nighttime DBP (mmHg) | 63.7±7.8 | 60±5.2 | 0.059 |

| 24h HR (bpm) | 77.9±8.2 | 70.5±10.9 | 0.009 |

| Daytime HR (bpm) | 79.5±8.6 | 72.9±11.1 | 0.024 |

| Nighttime HR (bpm) | 68.1±8.9 | 59±11.3 | 0.003 |

| Night/day ratio SBP (mmHg) | 0.91±0.04 | 0.87±0.07 | 0.014 |

| Night/day ratio DBP (mmHg) | 0.84±0.06 | 0.79±0.07 | 0.011 |

BMI: body mass index; bpm: beats per minute; DBP: diastolic blood pressure; HR: heart rate; mmHg: millimeters of mercury; SBP: systolic blood pressure; TBS: total body surface.

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression models were built to determine the dipper profile (Table 4). We found a significant relationship between medical rank and dipping BP pattern, which remains after adjusting for sleeping time. Being a Resident seems to increase the probability of non-dipping BP pattern more than 4.5 times compared to being a Consultant (p=0.033).

Univariate and multivariate analysis to determine dipping BP pattern profile.

| Dipping pattern | Univariate OR | Multivariate OR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-dipper | Dipper | |||

| Medical rank | ||||

| Residents | 22 (64.7%) | 12 (35.3%) | – | – |

| Consultants | 4 (23.5%) | 13 (76.5%) | 5.96 (1.70–25.07, p=0.008) | 4.86 (1.20–23.13, p=0.033) |

| Hours of sleep | ||||

| <5h | 15 (65.2%) | 8 (34.8%) | – | – |

| >5h | 11 (39.3%) | 17 (60.7%) | 2.90 (0.94–9.47, p=0.069) | 1.54 (0.40–5.73, p=0.522) |

OR: odds ratio.

The present study describes a potential link between being a Resident and the non-dipping BP pattern in physicians during prolonged shifts.

So far, recognized reasons for an absence of nocturnal BP dipping are sleep disturbance, obstructive sleep, apnea, obesity, high salt intake in salt-sensitive subjects, orthostatic hypotension, autonomic dysfunction, chronic kidney disease, diabetic neuropathy and old age.12 However, none of the participants of our study met these characteristics, except sleep disturbance during the shift.

Furthermore, non-dipping pattern was more frequent in Resident physicians (who were under 30 years of age), in contrast to previous studies showing an increased risk of a non-dipping BP related to an increasing age.12 This could be related to the fact that the study was carried out in university hospitals, where Resident physicians have increased workload because they are responsible for providing initial care to the patients.

It has been reported a significantly higher prevalence of HTN in people with sleep disturbances, such as airline pilots.13 Sleep disturbance has been described as the main cause of nocturnal hypertension.14 Anxiety disorder15 and insomnia16 have also been associated to nocturnal hypertension, probably resulted from excessive tension due to sleep disturbance during the night. However, we have not found a significant relationship between non-dipping BP pattern in Resident physicians, based on sleeping time, after adjusting in the multivariate analysis. Future studies with larger number of subjects are needed to determine if sleeping time influences the BP pattern in Resident physicians.

It has also been reported an association between history of shift work and rates of hypertension in both men and women.7 We have found that females were classified as a non-dipping pattern more frequently than males, but they were no differences by sex in night/day ratio SBP. Also, in our study, males and females had normal BP values, based on classification of hypertension grade1 and differences by sex are similar to those of the general population.

Some studies17,18 reported that circumstances which cause frequent awakenings during sleep increased heart rate (HR). Although we found that heart rate values are higher in individuals who sleep fewer hours, resting values do not exceed 80 beats/min, so we cannot consider it an added cardiovascular risk factor.1

Our study has several limitations. First, it is a cross-sectional study and results are limited to a low number of subjects of Caucasian population in a single Health area in the Autonomous Region of Asturias, in Northern Spain. Second, results are limited to a single time on each participant. Dipping status has a low reproducibility, with up to 40% of individuals from Europe19 changing status between repeated recordings.

In contrast, this is one of the few times that continuous BP measurement and non-dipping pattern are reported during shift work and the first time that BP is reported during a medical shift in a pediatric department, which could have implications for future studies on the impact of medical shifts on the health of the physicians. Moreover, the main strength of this study is that it was performed in a well-delimitated area, which allows a detailed study of each participant.

ConclusionsWe found a potential link between both being a Resident and, probably, having shorter sleeping time, and the non-dipping blood pressure pattern in physicians during prolonged shifts. Future studies with larger numbers of subjects are needed to corroborate the association between non-dipping pattern and shift work in medical shifts and obtain stronger conclusions.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding sourceThis research has not received specific aid from public sector agencies, the commercial sector or non-profit entities.

Financial disclosureThe authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

EthicsWe obtained approval from the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Autonomous Region of Asturias. All persons gave their written informed consent prior to their inclusion in the study.

All authors have read and approved the final revised version. They are willing to take responsibility for the entire manuscript. All authors substantially contributed to the writing (i.e. drafting and/or critical revision) of the manuscript.

We would like to thank Statistical Consulting Unit of the Scientific-Technical Services of the University of Oviedo for their cooperation in the statistical analysis.