To the Editor,

Nephrogenic ascites is a refractory type of ascites that affects patients with chronic kidney disease on haemodialysis.1 Although the pathogenesis of this condition is not completely clear, it appears that these patients with hypoalbuminaemia could have altered permeability of the peritoneal membrane and deficient lymph drainage.2 The diagnosis is made by exclusion,3 after ruling out other causes such as infection, liver disease, and heart failure. The best available option for treatment is daily haemodialysis treatment, the best alternatives for which are peritoneal dialysis and kidney transplantation.4 There have been documented cases of complete remission of ascites following kidney transplantation.5 Without treatment, the prognosis for nephrogenic ascites is very poor.4

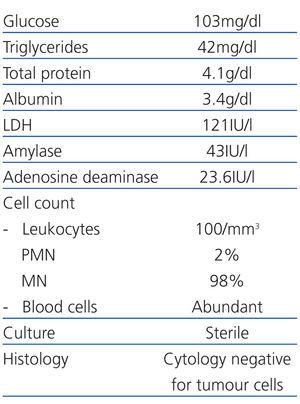

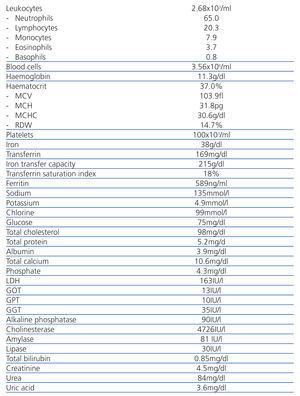

Here we present the case of a 66 year-old patient with no toxic habits and a history of arterial hypertension, atrial fibrillation, stroke in the left middle cerebral artery with residual right hemiparesis, aphasia, and dysarthria along with acute myocardial infarction. The patient started haemodialysis treatment in January 2005 due to renal failure secondary to post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis. The patient sought treatment in November 2010 with a progressive increase of the abdominal perimeter, with a physical examination indicative of ascites. We performed an abdominal ultrasound and observed abundant fluid in the abdominal cavity and a possible lesion of the head/body of the pancreas. Under the suspicion of tumour-based ascites, we decided to hospitalise the patient for analysis. We removed 5 litres of serosanguineous fluid by paracentesis and sent samples for testing. Given the cell counts (Table 1) and biochemical properties of the peritoneal fluid, we ruled out the possibility of infection; cultures also resulted sterile. A histological analysis ruled out the possibility of malignant tumour cells. We also confirmed negative serology tests for hepatitis C and B and HIV. Blood analyses (Table 2) did not reveal any significant abnormalities. We performed an abdominal axial computed tomography and magnetic resonance cholangiography, in which we observed a slightly over-sized liver, and the head of the pancreas was not visible. We asked the gastrointestinal department to perform an endoscopy in order to confirm the existence of a lesion on the pancreas as well as to look for evidence of possible oesophageal varices that would indicate portal hypertension from cirrhosis, in light of the liver disease demonstrated by the imaging tests. However, both conditions were ruled out and the patient was discharged.

Over a 6-month period, we administered 4 paracentesis sessions and sent samples for microbiological, histological, and laboratory analyses, with no changes from the aforementioned results. Considering the possibility of a cardiological origin for the ascites, we performed an echocardiogram, observing severe biventricular dysfunction with an ejection fraction of 22% and degenerative mitral and aortic disease with no haemodynamic repercussions. Despite a pathological echocardiogram, the patient never showed signs of heart failure, with no oedema or dyspnoea. Since a serum albumin-ascites gradient greater than 1.1 g/dL is indicative of portal hypertension with a 97% accuracy, we performed 2 tests, which resulted in values <1.1% and ruled out both liver disease and heart failure. Even so, we continued screening for a liver disease, ruling out viral, alcoholic, and other possible causes of an autoimmune liver disease. We also ruled out infections and peritoneal carcinomatosis.

Given the findings from numerous tests, the diagnosis appears to be compatible with nephrogenic ascites. Given the patient’s situation and inability for self-care, peritoneal dialysis is not an option. Kidney transplant is not an option either due to the associated comorbidities and the patient’s important bilateral iliac atherosclerosis. As recommended by the gastrointestinal department, evacuation paracentesis continues to be administered upon demand. We intensified the dialysis treatment and added intra-dialysis parenteral nutrition, with progressive improvements in the patient’s nutritional parameters and a complete disappearance of the ascites. Currently the patient is asymptomatic.

Conflicts of interest

The authors affirm that they have no conflicts of interest related to the content of this article.

Table 1. Characteristics of the ascites fluid

Table 2. Blood test results