Concomitant human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and visceral leishmaniasis is frequent and follows a torpid and recurrent course. Kidney involvement includes glomerulonephritis and tubular impairment. We report an uncommon case.

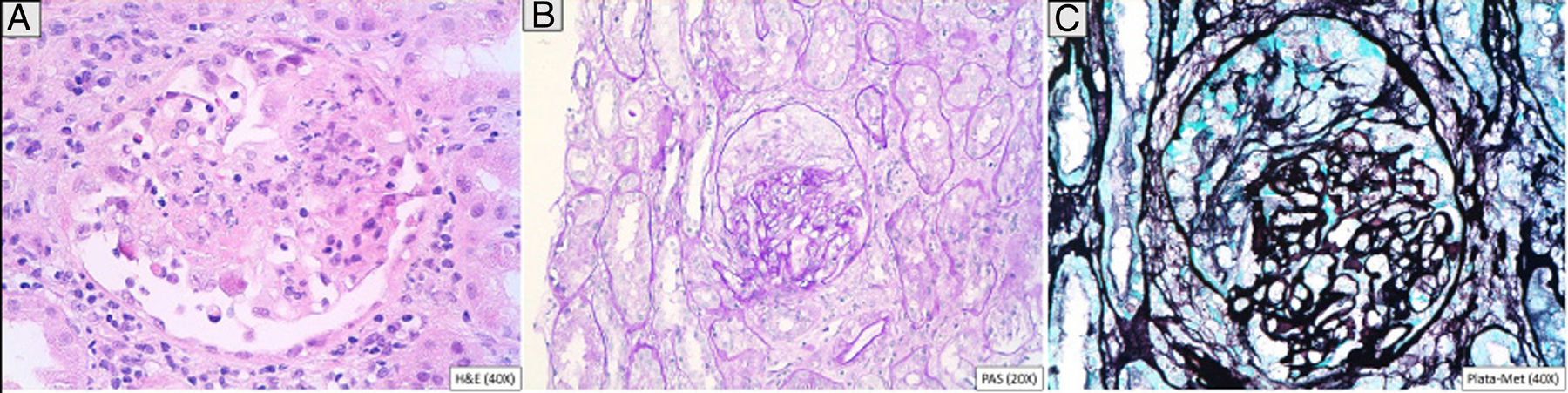

A 46-year-old man addicted to alcohol and parenteral drugs was diagnosed in 2006 with stage C HIV infection and hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotype 4. He started highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) in 2011, following his first episode of decompensated ascites due to cirrhosis with a Child-Pugh score of C, with portal hypertension, splenomegaly and pancytopenia. He voluntarily suspended HAART in May 2015 and restarted it in November 2016 (raltegravir, abacavir and lamivudine). A month later, with an undetectable viral load and no immune restoration (CD4 + T cells 74/mm3), he developed non-oliguric acute kidney failure (peak creatinine 5.7 mg/dl), mixed proteinuria of 2 g/day, microhaematuria and swelling on the back of the tongue (Fig. 1). A biopsy demonstrated severe epithelial dysplasia and mucosal candidiasis. Complementary tests revealed decreased C3, polyclonal gammopathy, increased immunoglobulins and kappa and lambda chains, and positive antinuclear antibodies (ANAs) (1/640). Cryoglobulins, a Mantoux test and serology (hepatitis B virus [HBV], syphilis, Toxoplasma) were negative. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) and Leishmania IgG and rK39 antigen in blood were tested and found to be positive. PCR for Leishmania in the tongue and bone marrow were negative. A kidney biopsy was performed in which six glomeruli were identified, one with foci of segmental necrosis with fibrin and two with crescents without thrombi (Fig. 2). Moderate chronic inflammation and fibrosis were seen in the interstitial space, with no tubular abnormalities. There were no signs of vasculitis. Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) was positive with a mesangial predominance for C3 (++), IgG (+), C1q and IgM (+), and negative for IgA and light chains. Amyloid was not identified with Congo red staining. Electron microscopy (EM) was not available. The patient started treatment with liposomal amphotericin B; three weeks later, his kidney function normalised and his urinary abnormalities improved. Two months later he started treatment for HCV with a sustained virologic response. After 16 months of follow-up in which prophylaxis with amphotericin was maintained, his glomerular filtration rate (GFR) was normal and minimal microhaematuria and albuminuria persisted. The patient's tongue swelling and acute kidney failure were interpreted as secondary to acute leishmaniasis.

Leishmaniasis is caused by the Leishmania infantum/chagasi protozoon in the Mediterranean, Asia and South America, and by Leishmania donovani in India and eastern Africa. Encompassed by the cells of the reticuloendothelial system, its multiplication induces severe polyclonal hypergammaglobulinaemia and pancytopenia. Subsequently, it enters the peripheral blood and may trigger a cutaneous, mucocutaneous, visceral or postvisceral dermatological condition. There are 1-2 million patients in the world, 500,000 new cases and 50,000 deaths per year.1–3 It primarily affects immunosuppressed, HIV-infected and transplant patients. In Spain, its incidence is 0.25/105 patients per year. From 1986 to 1994, 858 cases of concomitant infection were reported to the World Health Organization (WHO) Division for Control of Tropical Diseases in France, Italy, Portugal, Greece and Spain. Between 1.6% and 4.9% of cases of HIV will involve concomitant infection with Leishmania in southern Europe due to reinfection or reactivation.4 In HIV-infected patients, visceral leishmaniasis occurs in 60% of cases following treatment, since accumulation of the protozoon in atypical organs such as the kidneys affects the response of macrophages and dendritic cells and induces cytokine deregulation, an increase in IL-10, activation of CD8+ (cytotoxic) T cells, abnormal apoptosis, production of autoantibodies and immune complexes and incomplete responses to treatment, with frequent recurrences and chronic inflammatory reaction.5–7 In addition, it leads to CD4 + T cell depletion which worsens the course of the patient's HIV infection. Most concomitant infections occur when CD4 + T cell levels are below 200/μl. Diagnostic criteria include identification of the parasite in bone marrow and positivity of the rK39 antigen in blood during active infection, with specificity and sensitivity close to 100%.1 It is common to find complement consumption; positivity for rheumatoid factor; cryoglobulins3; and antiplatelet, anti-smooth muscle and anti-glomerular basement membrane (GBM) antibodies. In the kidneys,8 the damage is due to immune complex deposition, with activation of cytotoxic T cells and adhesion molecules.2 Initially the mesangium is affected with focal hypercellularity and granular deposits of IgG, IgM, C3 in the matrix, GBM (subendothelial, intramembranous and subepithelial) and interstitial space. If the immune complexes breach this barrier, they may become deposited in the glomerulus, thereby inducing epithelial and endothelial proliferation (MPGN). It is characteristic to find peritubular intramacrophage protozoa,5 interstitial damage9 which manifests with distal renal tubular acidosis (RTA).1,2,10 hyponatraemia, hypomagnesaemia, hypocalcaemia, hypokalaemia and hypouricaemia. Table 1 summarises the cases collected from the literature of concomitant infection with visceral leishmaniasis and HIV infection with kidney damage. In our case, the patient started with nephrotic syndrome and acute kidney failure with haematuria. The biopsy resulted in a diagnosis of necrotising glomerulonephritis. The fact that cryoglobulins were negative rendered the conclusion that it was not likely related to HCV infection. It is uncommon to identify the parasite in neither the bone marrow nor the kidney tissue, but the patient's positivity for the rK39 antigen and resolution of signs and symptoms after starting the treatment confirmed the diagnosis.

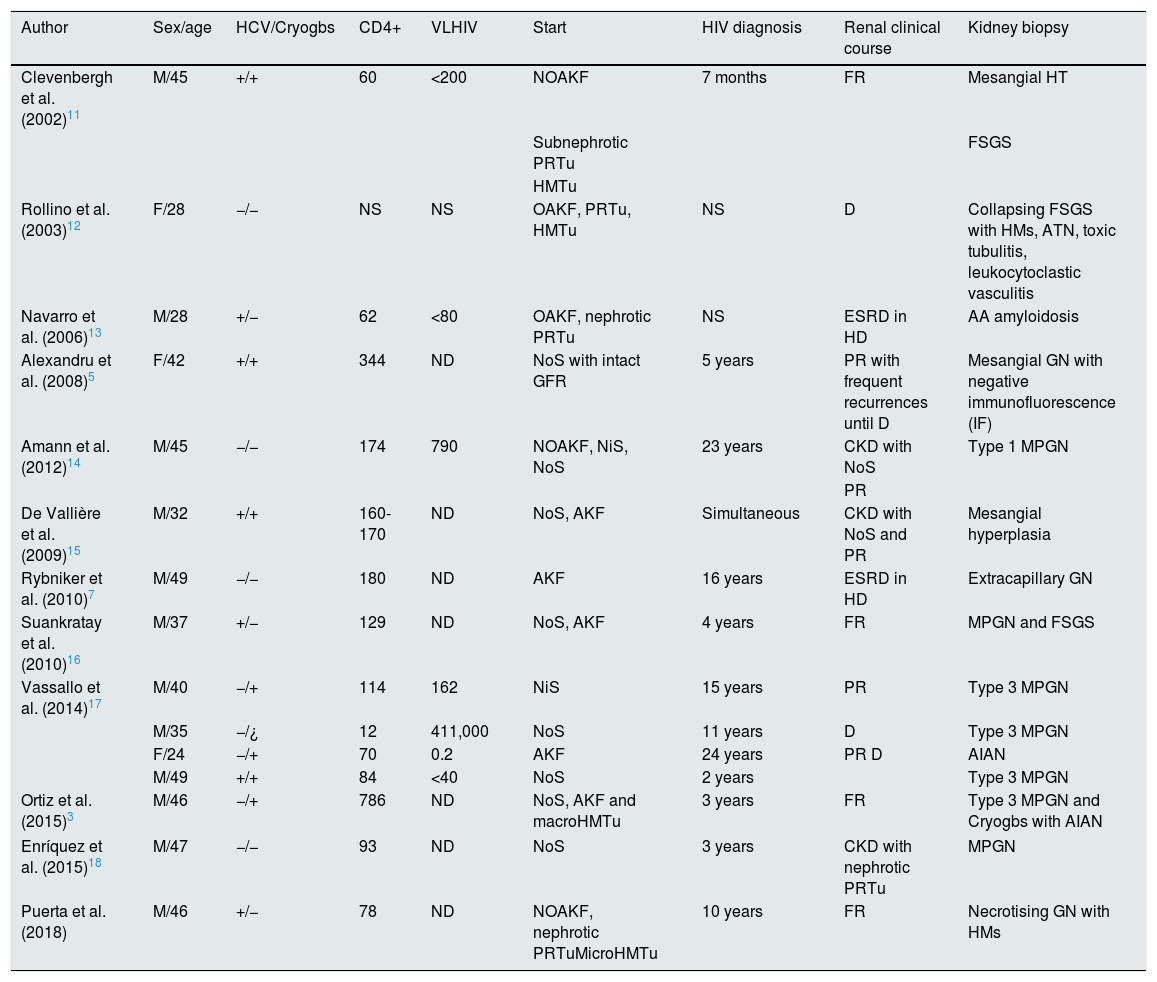

Cases published in the literature of concomitant visceral leishmaniasis and HIV infection with kidney damage.

| Author | Sex/age | HCV/Cryogbs | CD4+ | VLHIV | Start | HIV diagnosis | Renal clinical course | Kidney biopsy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clevenbergh et al. (2002)11 | M/45 | +/+ | 60 | <200 | NOAKF | 7 months | FR | Mesangial HT |

| Subnephrotic PRTu | FSGS | |||||||

| HMTu | ||||||||

| Rollino et al. (2003)12 | F/28 | −/− | NS | NS | OAKF, PRTu, HMTu | NS | D | Collapsing FSGS with HMs, ATN, toxic tubulitis, leukocytoclastic vasculitis |

| Navarro et al. (2006)13 | M/28 | +/− | 62 | <80 | OAKF, nephrotic PRTu | NS | ESRD in HD | AA amyloidosis |

| Alexandru et al. (2008)5 | F/42 | +/+ | 344 | ND | NoS with intact GFR | 5 years | PR with frequent recurrences until D | Mesangial GN with negative immunofluorescence (IF) |

| Amann et al. (2012)14 | M/45 | −/− | 174 | 790 | NOAKF, NiS, NoS | 23 years | CKD with NoS | Type 1 MPGN |

| PR | ||||||||

| De Vallière et al. (2009)15 | M/32 | +/+ | 160-170 | ND | NoS, AKF | Simultaneous | CKD with NoS and PR | Mesangial hyperplasia |

| Rybniker et al. (2010)7 | M/49 | −/− | 180 | ND | AKF | 16 years | ESRD in HD | Extracapillary GN |

| Suankratay et al. (2010)16 | M/37 | +/− | 129 | ND | NoS, AKF | 4 years | FR | MPGN and FSGS |

| Vassallo et al. (2014)17 | M/40 | −/+ | 114 | 162 | NiS | 15 years | PR | Type 3 MPGN |

| M/35 | −/¿ | 12 | 411,000 | NoS | 11 years | D | Type 3 MPGN | |

| F/24 | −/+ | 70 | 0.2 | AKF | 24 years | PR D | AIAN | |

| M/49 | +/+ | 84 | <40 | NoS | 2 years | Type 3 MPGN | ||

| Ortiz et al. (2015)3 | M/46 | −/+ | 786 | ND | NoS, AKF and macroHMTu | 3 years | FR | Type 3 MPGN and Cryogbs with AIAN |

| Enríquez et al. (2015)18 | M/47 | −/− | 93 | ND | NoS | 3 years | CKD with nephrotic PRTu | MPGN |

| Puerta et al. (2018) | M/46 | +/− | 78 | ND | NOAKF, nephrotic PRTuMicroHMTu | 10 years | FR | Necrotising GN with HMs |

AIAN: acute immunoallergic nephritis; AKF: acute kidney failure; ATN: acute tubular necrosis; CKD: chronic kidney disease; Cryogbs: cryoglobulins; D: death; ESRD: end-stage renal disease; F: female; FSGS: focal segmental glomerulosclerosis; FR: full recovery; GN: glomerulonephritis; HD: haemodialysis; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; HMs: half-moons; HMTu: haematuria; HT: hypertrophy; M: male; MPGN: membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis; ND: not detectable; NiS: nephritic syndrome; NOAKF: non-oliguric acute kidney failure; NoS: nephrotic syndrome; NS: not specified; OAKF: oliguric acute kidney failure; PR: partial recovery; PRTu: proteinuria; VL: viral load.

Please cite this article as: Puerta Carretero M, Ortega Díaz M, Corchete Prats E, Roldán Cortés D, Cuevas Tascón G, Martín Navarro JA, et al. et al. Glomerulonefritis necrosante en un paciente con VIH, VHC y leishmaniasis visceral. Nefrologia. 2020;40:481–484.