To the Editor,

Autoimmune processes affecting the kidneys are heterogeneous clinical entities and their differential diagnosis is complex. The best example is systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), whose pleomorphisms can range from skin or joint lesions to lupus nephritis (LN). Its diagnostic criteria were revised in 1997 by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR), and by following them, the syndrome can be defined with a sensitivity and specificity of 96%.1 However, atypical clinical profiles are hard to interpret, and the symptoms in such cases are often anachronical and non-specific.

In this context, we present the case of a 40 year old patient with a history of smoking, obesity and high blood pressure (HBP) with no pharmacological treatment. The patient was admitted to the nephrology department because he had experienced fever, diarrhoea/vomiting, weight loss, and progressive decrease in diuresis for 3 weeks. Laboratory results then showed severe renal dysfunction (urea 383mg/dl; creatinine 20.3mg/dl), hypoalbuminaemia (2.3g/dl) and anaemia (haematocrit 20%; haemoglobin 6.9g/dl; mean cell volume 88 fL). Meanwhile, complementary tests found microhaematuria, blood clotting disorders (prothrombin activity 89%; haptoglobin 298mg/dl; reticulocytes 1.5%; low schistocytosis; positive direct Coombs test) in addition to abnormalities found by ultrasound (normal-sized kidneys with cortical hyperechogenicity). In light of these results, and suspecting a glomerular process, with incomplete data suggesting haemolytic anaemia, we performed emergency haemodialysis and a blood transfusion.

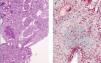

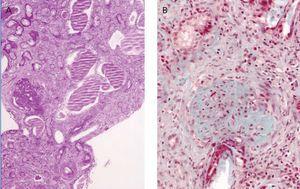

Other results gathered at the same time were as follows: negative stool and blood cultures; negative serology for bacteria and parasites; viral serology for hepatitis B, C and HIV showing positive IgM and IgG for cytomegalovirus (CMV), Coxsackievirus, herpes simplex and herpes varicella zoster; and decreased C3 fraction (51mg/dl). A renal biopsy showed generalised glomerulosclerosis in 60% of the sample, with fibrous crescents (some glomeruli showing poorly defined margins), cystic tubular atrophy, fibrosis and interstitial lymphocytic infiltrate. There were also signs of proliferative arteriopathy having to do with HBP (Figure 1).

With a presumed diagnosis of rapidly progressive extracapillary glomerulonephritis (GN) against the diagnosis of SLE, we administered adjuvant immunosuppressive drugs with dialysis (prednisone 1mg/kg/day and azathioprine (AZA) 2mg/kg/day) while waiting for immunology test results. Tests found the following results: ANA (+) at a titre of 1:640; anti-dsDNA (+) 126IU/ml; anti-Sm (+) 1.54U/ml and c-ANCA (proteinase 3-specific cytoplasmic antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies) (+) 52.8U/ml. Anticardiolipin and lupus anticoagulant antibodies were negative. This was sufficient to diagnose the syndrome as WHO class VI lupus nephritis in a systemic context (syndrome met 5 of the ACR criteria: nephritis, serositis, abnormal blood tests, ANA at high titres, anti-dsDNA and anti-Sm). Despite the positive results and proposed treatment, the patient’s renal function never recovered and urine output remained below 500cc/24h.

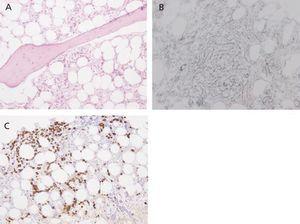

Eight months after symptom onset (during which time the patient’s anaemia could not be controlled correctly despite maintaining immunosuppressant treatment) the patient suffered from numerous complications. These included acute coronary syndrome (ACS), an episode of diarrhoea and high fever that did not respond to either astringent or antibiotic treatment, and lastly, severe pancytopoenia (2320 000 red blood cells/µl, 890 leukocytes/µl, 51 000 platelets/µl), with a low reticulocyte production index (0.2%) and negative direct and indirect Coombs test. As there was a strong suspicion of a lupus flare and/or myelotoxicity, the recommendation was to intensify immunomodulatory treatment with a methylprednisolone bolus and discontinue AZA. In addition, we also decided to administer granulocyte colony-stimulating factors (filgrastim: 480µg/sc/day). However, there was no megakaryocyte response, and a bone marrow biopsy revealed intense hypoplasia with developmental anomalies, and glycophorin-negative proerythroblasts which might be linked to SLE, although it was impossible to rule out simultaneous chronic infection with parvovirus B19 (Figure 2). A new viral serology test also confirmed the presence of IgG antibodies (against the diagnosis of parvovirus) along with a blood count of 68 000 copies/ml of CMV DNA. It was then decided to start foscarnet 50mg/kg/day to prevent the myelotoxic effect of ganciclovir, and intravenous immunoglobulin (60g/day). This association did not provide any haematological benefits and was manifestly unable to prevent a new episode of bloody diarrhoea complicated by a pulmonary haemorrhage which could not be resolved even by using combined treatment with daily dialysis and plasmapheresis. In the end, the patient died in the intensive care unit due to sepsis secondary to infection with Escherichia coli.

In conclusion, the case described is an excellent example of atypical SLE with severe LN with no classical signs of the disease such as skin and joint disorders, with wasting syndrome (fever, anaemia) and severe renal failure being predominant. The main underlying conditions were generalised glomerulosclerosis/fibrous crescents/interstitial disorders (compatible with advanced extracapillary GN) without the lesions typical of proliferative forms of LN.2 In addition, obtaining a positive test for c-ANCA antibodies (antiproteinase 3) instead of p-ANCA was also uncommon; p-ANCA is more prevalent according to most authors (present in 15%-30% of cases of SLE).3-5 Complications that arose after diagnosis included ACS as an expression of systemic inflammation and atherosclerosis, and evolution of the initial haemolytic anaemia to irreversible medullary aplasia of unknown aetiology (possibly secondary to chronic infection with parvovirus B19).6,7 The patient did not respond to discontinuing AZA or to intensive treatment with intravenous gammaglobulins, plasmapheresis or colony-stimulating factors. This fact, combined with the array of symptoms caused by CMV (enteritis and pulmonary haemorrhage) defined the final outcome and made us re-consider that both infections were co-existing opportunistic entities, and perhaps, the agents triggering the lupus flare.7-10

Conflicts of interest

The authors affirm that they have no conflicts of interest related to the content of this article.

Figure 1. Renal Biopsy. Severe glomerulosclerosis and tubular lesion

Figure 2. Bone marrow biopsy. Developmental hypoplasia