The prevalence of chronic infection with the hepatitis C virus (HCV) in patients with chronic kidney disease is higher than in the general population. The estimated prevalence is 13% in haemodialysis, with wide variations geographically and between units in the same country.

A liver biopsy is a useful tool for deciding whether to start antiviral therapy and to exclude concomitant causes of liver dysfunction. Examples of this include non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, whose incidence is on the rise, and haemosiderosis, which may affect the progression of the disease and determine the response to antiviral therapy. In addition, the transjugular approach can be used to measure the hepatic venous pressure gradient and confirm the existence of portal hypertension.

Chronic hepatitis due to HCV has been shown to reduce survival in haemodialysis, renal transplantation and graft survival. It is the fourth leading cause of death and the leading cause of post-renal transplantation liver dysfunction. HCV behaves as an independent risk factor for the occurrence of proteinuria; it increases the risk of developing diabetes mellitus, de novo glomerulonephritis and chronic allograft nephropathy; it leads to a deterioration in liver disease and causes a greater number of infections. An increased frequency of fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis has also been described which, together with the rapid evolution to cirrhosis, can significantly increase morbidity and mortality and lead to the need for liver transplantation. In addition, immunosuppression in renal transplantation predisposes a reactivation of HCV. However, as the pharmacokinetics of interferon and ribavirin is impaired in kidney failure and their use has adverse effects on function and graft survival, a combination therapy must be limited to non-transplanted individuals with an estimated glomerular filtration rate greater than 50ml/min, and with the interferon being used as monotherapy in dialysis. The fact that a quarter of HCV-positive patients evaluated for a renal transplant have bridging fibrosis or cirrhosis in the liver biopsy may renew renal pre-transplant treatment planning.

La prevalencia de la infección crónica por el virus de la hepatitis C (VHC) en pacientes con enfermedad renal crónica es mayor que en la población general. En hemodiálisis, se estima una prevalencia del 13%, con una amplia variabilidad geográfica y entre las unidades de un mismo país. La biopsia hepática es una herramienta útil para decidir el inicio de la terapia antiviral y excluir causas concomitantes de disfunción hepática, como la hepatopatía grasa no alcohólica, cuya incidencia está en auge, y la hemosiderosis, que pueden afectar a la progresión de la enfermedad y condicionar la respuesta al tratamiento antiviral; además, la vía transyugular se puede utilizar para medir el gradiente de presión venoso hepático y confirmar la existencia de hipertensión portal. La hepatitis crónica por el VHC ha demostrado reducir la supervivencia en hemodiálisis y en el trasplante renal, así como la supervivencia del injerto. Constituye la cuarta causa de mortalidad y la principal causa de disfunción hepática postrasplante renal. El VHC se comporta como un factor de riesgo independiente para la aparición de proteinuria, aumenta el riesgo de desarrollar diabetes, una glomerulonefritis de novo o una nefropatía crónica del injerto, de empeorar la enfermedad hepática y de provocar un mayor número de infecciones. También se ha descrito un incremento de la frecuencia de hepatitis colestásica fibrosante que, junto a la evolución acelerada a cirrosis, puede elevar significativamente la morbimortalidad y conllevar la necesidad de un trasplante hepático. Además, la inmunosupresión en el trasplante renal predispone a la reactivación del VHC. Sin embargo, como la farmacocinética del interferón y la ribavirina está alterada en la insuficiencia renal y su uso tiene efectos adversos sobre la función y la supervivencia del injerto, la terapia combinada se limita a los individuos no trasplantados con un filtrado glomerular estimado mayor de 50 ml/min y en diálisis suele emplearse el interferón en monoterapia. El hecho de que una cuarta parte de los pacientes VHC-positivos evaluados para trasplante renal tenga fibrosis en puente o cirrosis en la biopsia hepática puede renovar el planteamiento del tratamiento pretrasplante renal.

INTRODUCTION

The World Health Organisation estimates the global prevalence of chronic infection with the hepatitis C virus (HCV) to be 3%, with wide geographic variation: less than 5% in most Northern European countries, about 10% in southern Europe and the United States, and between 10%-50% and up to 70% in many developing countries, including parts of Asia, Latin America and North Africa. The incidence of HCV infection has been reduced to less than 1%-2% in developed countries.1-3

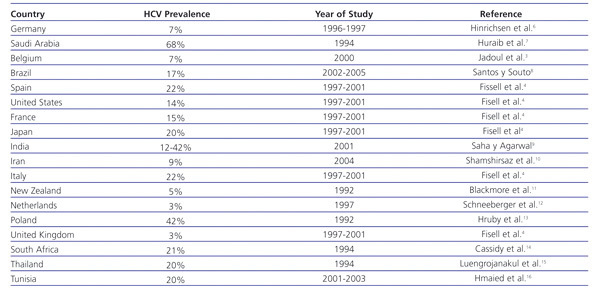

HCV infection in patients with stage 5 chronic kidney disease (CKD) is higher than in the general population. In haemodialysis patients, there is a prevalence of 13%, with a range of 1%-70%4 (Table 1). Furthermore, the prevalence of HCV is highly variable among haemodialysis units within the same country.5 In Spain, the prevalence of HCV infection in haemodialysis in 1997-2001 was estimated at 22%.4

In renal transplant patients, the prevalence of HCV infection ranges between 7% and 40%, also with a wide geographic and demographic variation.4,17-19

Up to 55%-85% of those infected with HCV progress to the chronic stage,20-23 and 5%-25% of these develop cirrhosis at 25-30 years.20,24 Individuals with cirrhosis have a higher risk of hepatocellular carcinoma than the non-cirrhotic population. In Spain, HCV is currently the main risk factor associated with hepatocellular carcinoma,25 although the risk varies with the extent to which the liver is affected. It is less than 1% annually in patients with chronic hepatitis without significant fibrosis, and reaches 3%-7% annually for cirrosis.26 Once liver cirrhosis is found, there is a risk of liver hepatocellular carcinoma continuing to develop, despite having a sustained viral response to treatment.27 Several factors for progression to cirrhosis have been identified: advanced age, obesity, immunosuppression, alcohol consumption greater than 50g/day,28-31 and a more rapid evolution to cirrhosis has been described in renal transplant patients.32-34

LIVER HISTOLOGY: ROLE OF BIOPSY

A liver biopsy is of substantial value in assessing the severity of liver disease in chronic HCV infection, in relation to the degree of fibrosis and necroinflammatory activity, as well as for excluding other concomitant causes of liver dysfunction. These include non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, whose incidence is on the rise, and haemosiderosis, which may affect the progression of the disease and determine the response to treatment.35-38 The KDIGO guides (Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes)39 recommend a liver biopsy in the liver disease study of patients eligible for renal transplantation. The AASLD guide (American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases) limits it to HCV-positive patients with genotypes 1 and 4, but considers it unnecessary in genotypes 2 and 3,40 given that over 80% of patients (with normal renal function) achieve a sustained viral response.

The METAVIR score evaluates necroinflammatory activity (grade) and fibrosis (stage). It consists of a coding system of two letters and two numbers: A= histological activity (A0= no activity, A1= mild activity, A2= moderate activity, A3= severe activity); and F= fibrosis (F0= no fibrosis, F1= portal fibrosis without septa, F2= portal fibrosis with few septa, F3= numerous septa without fibrosis, F4= fibrosis).41 It requires a high quality liver biopsy of at least 2cm in length, with more than 5 portal tracts, to calculate an appropriate METAVIR score.42,43

According to the KDIGO guidelines, patients on the waiting list for a kidney transplant who do not respond to or refuse antiviral treatment must undergo a liver biopsy every 3-5 years, depending on the initial METAVIR score (every 3 years for a METAVIR score of 3, and every 5 years for a METAVIR score of 1-2).39 There is no evidence to support this recommendation, although it has been shown that liver disease progresses in patients on dialysis.17,34 Liver damage markers like GPT do not accurately reflect the histological severity of liver disease of CKD patients, and up to 25% of patients with HCV infection evaluated for renal transplantation have bridging fibrosis or cirrhosis in the liver biopsy (METAVIR>3).44-49 No definitive studies have investigated whether the histological stage of the pre-transplant biopsy predicts post-transplant liver disease and its outcomes. However, the presence of cirrhosis in the pre-transplant liver biopsy has been associated with a 26% survival at 10 years.50 Several studies have shown that 19%-64% of renal transplant patients infected with HCV have post-transplant liver disease, compared with only 1%-30% of patients not infected.18,50-56 Most studies are retrospective, with patients without a pre-transplant liver biopsy. This could result in an underestimation of advanced liver disease, given the increase in the rate of decompensated liver disease. Studies without a pre-transplant liver biopsy, but with a post-transplant sequential liver biopsy, have shown that liver histology may progress in 20% of patients.57,58 Since there is a 6%-8% annual mortality risk in patients on a transplant waiting list,59 it seems reasonable to monitor their liver disease to check if a renal transplant is still appropriate for their condition. Liver damage before renal transplantation is an independent predictor of poor long-term survival.50

Coagulopathy secondary to hepatocellular dysfunction and thrombocytopaenia due to portal hypertension and hypersplenism poses an increased risk of bleeding.60 Due to the presence of ascites in CKD patients, and because of the added risk of increased bleeding from platelet dysfunction associated with uraemia, haemodialysis anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy, a liver biopsy via the transjugular or transfemoral route is often recommended. This can provide additional diagnostic information, such as the hepatic venous pressure gradient, to confirm the existence of portal hypertension.39,40

Desmopressin (DDAVP, 0.3mg/kg) has been used more often immediately before liver biopsy in CKD patients. However, we were not able to find defined serum creatinine level or glomerular filtration rates which should be used for desmopressin indication.61

The utility of non-invasive markers (Index of Forns, APRI or FIB-4) in the study of liver damage in patients with CKD and HCV infection is not known at present.62 There were hopes for transient elastography (FibroScan), which has failed to replace the biopsy: it has not been approved by the FDA (Food and Drug Administration), the error rate is higher in obese patients and may be overestimated in acute hepatitis, which is associated with high necroinflammatory activity and low or nil fibrosis.63,64

TREATMENT

The treatment of choice for chronic HCV hepatitis is conventional or pegylated interferon, alone or in combination with ribavirin. The antiviral treatment should be individualised, depending on the severity of the liver disease, the possibility of serious adverse effects, variability in the response to treatment, the presence of comorbidity (particularly renal failure) and the patient's decision.40 Individuals with CKD have lower to normal levels of transaminases45,65-67 compared to those without CKD. Traditionally, it was considered that subjects with genotype 1 and persistently normal transaminases had minimal hepatic fibrosis and were thus not appropriate for treatment. Today, it has been shown that up to 25% of these patients have significant fibrosis, and that their response to treatment is similar to patients with elevated transaminases.68-74 Patients with extrahepatic manifestations have to be treated, regardless of the severity of the liver disease.75

In individuals with normal renal function, antiviral therapy is aimed at eradicating HCV infection to improve liver histology, which in the long term results in lower morbidity and improved survival. In patients with CKD, the treatment of HCV is even more relevant, because chronic hepatitis has been shown to reduce survival in haemodialysis, renal transplantation and renal graft survival,18,50-56,76-78 compared with non-infected patients. This is partly due to the progression of liver disease, the rapid evolution to cirrhosis and/or appearance of hepatocellular carcinoma.18,32-34,50,56,79 HCV infection is the leading cause of renal post-transplant liver dysfunction and the fourth cause of mortality in this group.33 HCV behaves as an independent risk factor for the occurrence of proteinuria,53,80 it increases the risk of developing diabetes after transplantation,81-83 de novo glomerulonephritis,84-87 and chronic allograft nephropathy, and worsens liver disease and causes more infections.39 In addition, immunosuppression in renal transplantation enhances HCV reactivation. In particular, steroids have been associated with a 10 to 100 fold increase in the viral load.88 They should therefore be avoided or minimised in HCV-positive patients.89 In addition, an increased frequency of fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis has been described which, together with the rapid evolution to cirrhosis, may significantly increase morbidity and mortality, leading to the need for a liver transplant.90,91

However, antiviral therapy in CKD remains controversial. There are no comparative studies to support the decision of an appropriate antiviral treatment. Most haemodialysis studies have investigated the use of conventional alpha interferon (3MIU 3 times a week) or pegylated alpha interferon (alpha 2a, 135µg/week; or alpha 2b, 50µg/week, or 0.5-1µg/kg/week) in monotherapy. The results are different but, generally, there is a low sustained viral response (19%-75%) and significant drug intolerance (30%-50% of dialysis patients interrupt the therapy).92-95 The American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) and the AASLD recommend the use of reduced doses of pegylated alpha interferon in monotherapy, and consider the association of ribavirin as a contraindication in patients with an estimated glomerular filtration rate less than 50ml/min.40,96,97-104 There is little experience with the ribavirin combination therapy (200mg, 3 times a week or 200mg/24h) in dialysis. Better results have been suggested, although the studies were for few case series with a very limited number of patients.105-110 A recent meta-analysis of existing clinical trials on combination therapy in dialysis showed that about half of the patients obtained a sustained viral response.111 The risk of severe anaemia due to secondary haemolysis makes it difficult to use, although some researchers have used it based on serum drug levels, obtaining uneven results.106-110,112 Available data, however, are encouraging and its use may be indicated in centres where patient are treated by hepatologists and nephrologists. Antiviral treatment in renal transplant recipients is rare except in cases with limited therapeutic alternatives or severe cholestatic hepatitis.90,91 The main drawback of antiviral treatment before transplantation is the delayed inclusion of the patient on the waiting list, without being able to ensure HCV eradication due to the low response figures.

Therefore, all haemodialysis patients with detectable HCV RNA and an F0-F2 METAVIR score should be considered as candidates for treatment with alpha interferon. The bridging fibrosis patients with compensated cirrhosis should also receive antiviral therapy, and be eventual candidates for renal transplantation if they achieve a sustained viral response. Patients with decompensated cirrhosis should be evaluated for a combined kidney and liver transplant.40

In light of the impact of chronic HCV infection in renal transplantation, it is recommended that patients with CKD are treated prior to undergoing the transplant.113,114 However, despite the evidence on the benefits of antiviral treatment in patients with chronic HCV infection and CKD prior to renal transplantation, only a few kidney transplant protocols recommend treatment against HCV, and it is not usually listed as a pre-transplant criterion.115-117 In fact, the evaluation before a kidney transplant for HCV-positive patients on renal replacement therapy shows that, as well as not considering treatment for HCV before transplantation, hepatology monitoring of these patients on dialysis is virtually nonexistent in many cases. This may be due to the inherent complexity of CKD treatment, leading the nephrologist to assume all the patient pathology in haemodialysis.

Further studies are needed to assess the clinical situation and monitoring of HCV hepatitis in patients on haemodialysis, to identify improvements and involve both nephrologists and hepatologists in its management.

Table 1. Prevalence of HCV infection in haemodialysis