To the Editor:

Peritoneal dialysis (PD) is one of the treatment options available for replacing renal function in patients with chronic renal failure.

The success of PD as a dialysis technique depends heavily on correct catheter placement into the peritoneal cavity. Several different methods are available for this purpose: laparoscopy, the percutaneous approach using the Seldinger technique or trocars, and surgical.1 No evidence exists regarding which technique provides the best results, although each technique obviously involves certain advantages and disadvantages. Purely surgical approaches require the availability of surgeons, operating rooms, and anaesthesia. Percutaneous techniques can be performed by nephrologists and/or radiologists in a properly equipped room, which obviates the need for waiting lists.2 Recent results were published regarding the safety of laparoscopy as compared to open surgery and regarding radiologist-assisted percutaneous techniques.3,4 Despite these advances, surgical techniques continue to be the most commonly used.

We enjoy a tight collaboration with the general surgery department at our hospital, which has led to our use of laparoscopy as the technique of choice. Here, we present our experience in the placement of peritoneal catheters.

MATERIAL AND METHOD

We reviewed 80 patients who received PD catheters between January 2007 and January 2012. Demographic and clinical data were collected prospectively.

Demographic data: The sample consisted of 46 males and 34 females, with a mean age of 57 years (range: 18-91 years).

Surgical technique: The intervention took place in a conventional surgical operating room. Under general anaesthesia and a sterile operating field, a 12mm Hasson trocar was placed in the supra-umbilical zone for the insertion of a 30º laparoscopic camera. Next, pneumoperitoneum at 12mmHg of pressure was achieved. The peritoneal cavity was explored, in particular the lower pelvis, looking for large zones free of adhesions for optimal catheter placement. A second 5mm laparoscopic trocar was inserted in the left para-rectal zone. The catheter was inserted with a guide through this second trocar. Under the visual control provided by the laparoscopic camera, the point of the catheter was advanced until reaching the ideal location in the pouch of Douglas. Only rarely, the presence of adhesions or connective tissue required the insertion of a third 5mm trocar in order to use instrumentation (forceps, hooks, or scalpel) in order to dissect and cauterise the impeding structures. After removing the guide and trocar, the internal catheter cuff was left in the zone immediately below the musculature. Finally, a subcutaneous tunnel was created for the distal end of the catheter.

RESULTS

A total of 89 surgeries were performed. In 9 cases, we documented poor catheter function during the first couple of weeks after catheter placement (less than 15 days). All of these cases required a second laparoscopic procedure due to the inability to recover the catheter through conservative techniques. In all of these cases, the catheter became trapped by the omentum or adhesions. A new catheter was placed, in addition to an omentectomy and clearing of adhesions. We did not observe any cases of infection of the catheter orifice, peritonitis, immediate hernia, haemoperitoneum, or death as an immediate consequence of the interventions.

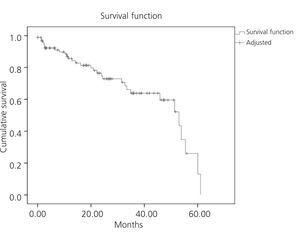

Mean catheter survival during this period was 42 months, with a 95% confidence interval of 36.8-58.7 months (Figure 1).

CONCLUSIONS

- Laparoscopy is a safe technique with very good results for long-term catheter functioning.

- The primary issues immediately following catheter placement were secondary to poor catheter functioning, above all due to omental trapping. We did not observe any severe complications.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest related to the contents of this article.

Figure 1. Survival