We report the case of a patient, male with acute kidney failure and haemolytic anaemia in the context of secondary malignant hypertension (HTN) and anabolic steroid user.

Malignant HTN is a disease characterised by a marked rise in blood pressure (BP) (systolic>180–190mmHg and diastolic>120–130mmHg), grade III–IV hypertensive retinopathy and abnormal kidney function.1,2 It is often accompanied by microangiopathic haemolytic anaemia (schistocytes in peripheral blood) with high LDH, undetectable haptoglobin, reticulocytosis, thrombocytopenia and a negative Coombs test. There may be proteinuria and micro- or macrohaematuria. An immunology study is usually negative and is useful to rule out connective tissue diseases. Lesions often develop in other target organs, leading to, for example, left-sided heart failure or hypertensive encephalopathy. Therefore, it is necessary to perform an electrocardiogram, a chest X-ray, an echocardiogram or a brain scan.3

Furthermore, the use of anabolic steroids has risen to alarming proportions in recent decades. Although effects on kidney function are uncommon, some cases have been documented in which a combination of anabolic steroids and creatine supplements has caused kidney damage. Anabolic steroids have a known effect on hypernatraemia, accompanied by an increase in urinary excretion of potassium and hydrogen ions, resulting in hypokalaemic alkalosis.4,5

We report the case of a 37-year-old male with hypertension known for the last 10 years, with no treatment, who regularly practised bodybuilding; took intramuscular anabolic steroids (testosterone and stanozolol), growth hormone and oral creatine; and followed a protein-rich diet. He visited the Emergency Department due to signs and symptoms of general malaise, nausea, headache and blurred vision that had lasted for one week. He was found to have high BP (250/180mmHg) and severe acute kidney failure. Complementary tests revealed anaemia and thrombocytopenia (haemoglobin 9.9g/dl, haematocrit 28.4%, platelets 91,000/mm3) as well as the above-mentioned kidney failure (urea 246mg/dl, creatinine 23.5mg/dl). An immunology study was negative (except for a slight decrease in C3 and C4 fraction), with proteinuria of 1.7g/24h and oligoalbuminuria of 491mg/l. A peripheral blood smear showed real thrombocytopenia and schistocytes (2.1%). Venous blood gases were normal and potassium levels were at the lower limit of normal (this was likely an effect of the anabolic steroids). Given his haemolytic anaemia with mild thrombocytopenia and schistocytes on smear testing, the patient was thought to have microangiopathic haemolytic anaemia. A brain CT scan was performed (to rule out brain damage secondary to HTN). The scan showed a punctiform image in the caudate nucleus that was not suggestive of acute haemorrhagic lesion.

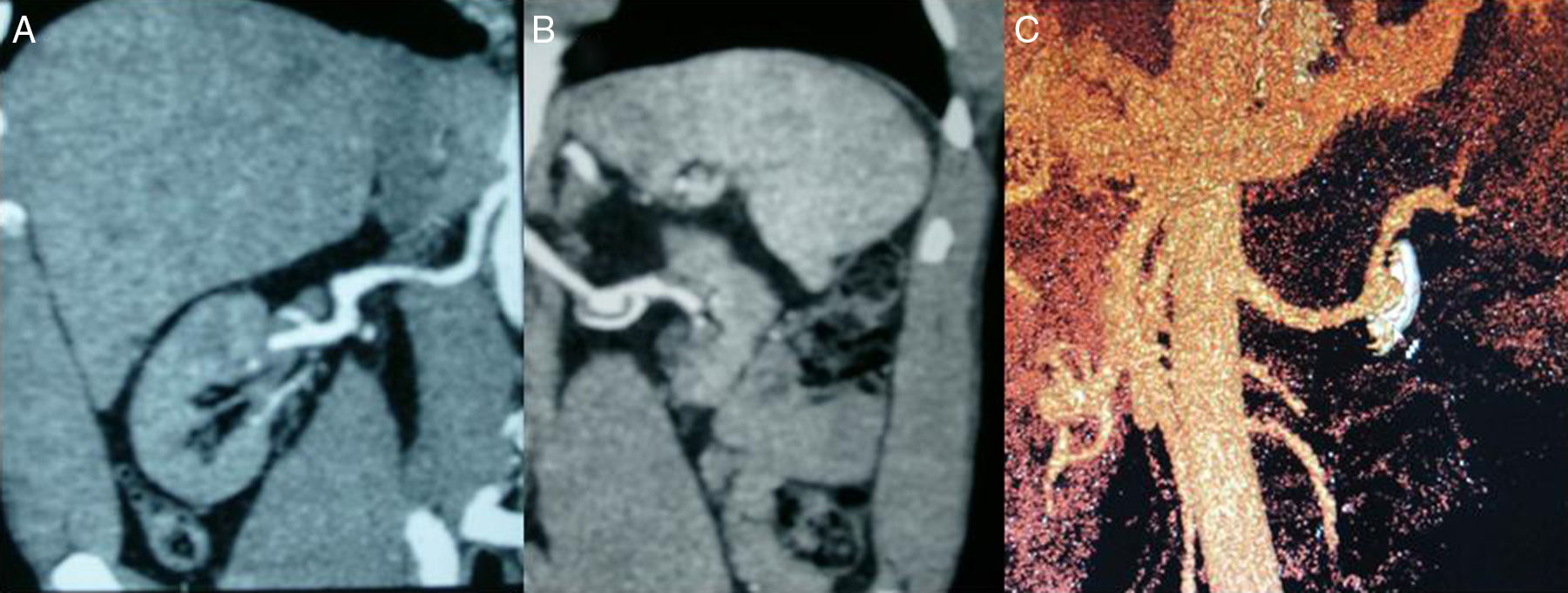

Despite intravenous hypotensive treatment (labetalol and nitrites), the patient's BP levels remained high. Therefore, it was decided to admit the patient to the Intensive Care Unit and start acute haemodialysis and plasmapheresis simultaneously on an emergency basis. A dilated eye fundi examination was performed and yielded a result consistent with grade IV hypertensive retinopathy. A kidney ultrasound showed destructured kidneys with poor corticomedullary differentiation and obvious asymmetry. An angio-CT scan (Fig. 1) ruled out left renal artery stenosis, but revealed an aneurysm in the left renal artery 2cm in diameter with a calcified and thrombosed wall. An ECG showed signs of left ventricular hypertrophy and diastolic overload, and an echocardiogram showed severe concentric LV hypertrophy with preserved systolic function.

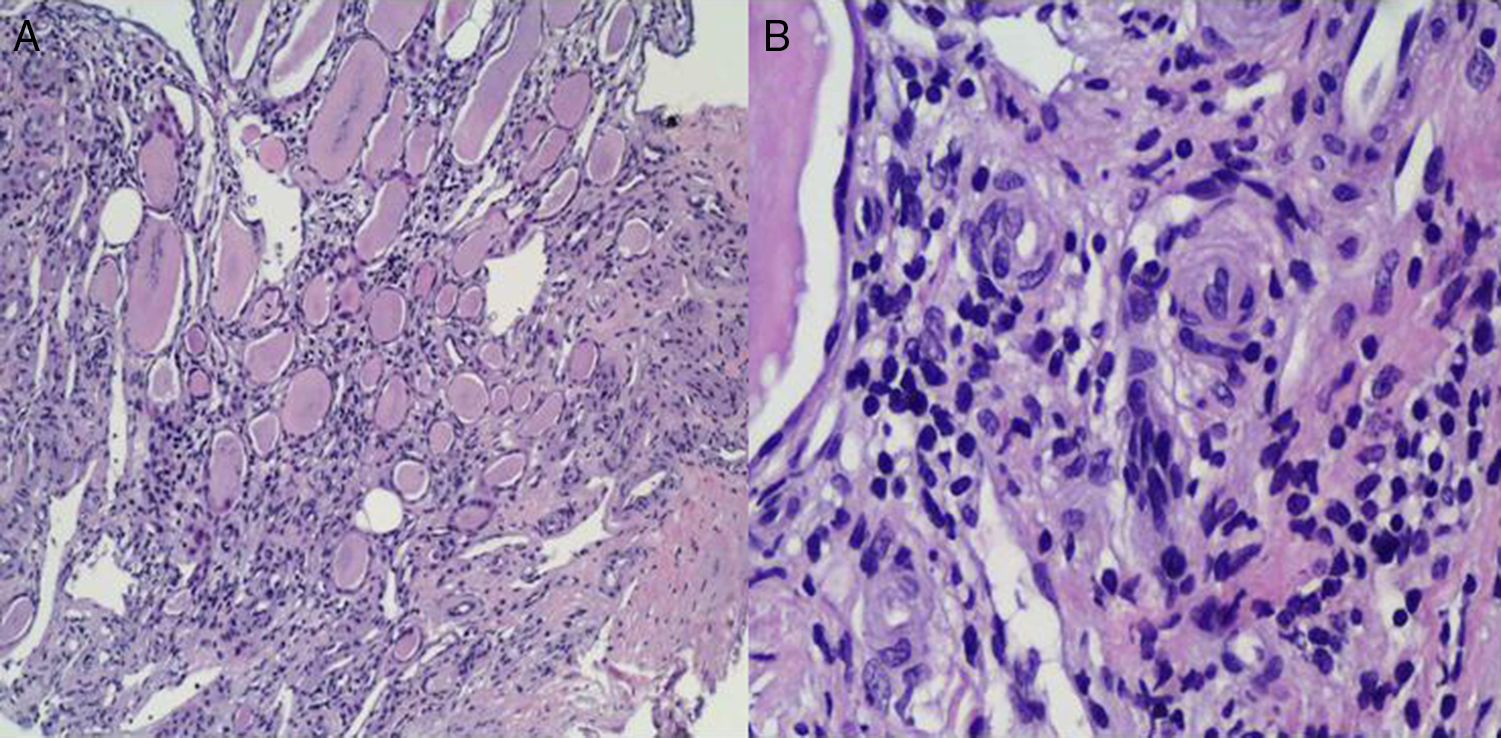

As soon as the patient was admitted to the Intensive Care Unit, while he was being administered IV nitrites and labetalol, oral treatment with an ACE inhibitor (enalapril 20mg/12h) was started. After he had been hospitalised for 24h, he started to show gradual clinical improvement: his BP levels stabilised and his platelet count recovered. This made it possible to discontinue his IV hypotensive medication and plasmapheresis after 4 sessions. A kidney biopsy (Fig. 2) yielded limited material, mainly medulla, and no cortex, due to technical difficulties given the patient's extensive muscle mass. Indications of chronic interstitial kidney disease and, in small vessels, indications suggestive of malignant HTN were seen. As the patient met certain obvious clinical criteria and had highly suggestive dilated fundus examination and histology results, he was thought to have accelerated malignant HTN. Associated glomerular disease could not be ruled out due to a lack of glomeruli in the kidney sample.

(A) Clear histological signs of chronic interstitial kidney disease characterised by tubular dilation rich in material with a colloid-like appearance offering a typical picture of “renal thyroidisation”. (B) In small vessels and the medullary region, myointimal proliferation is observed with luminal occlusion and initial middle-layer proliferation with incipient “onion-layer” formation.

Treatment of malignant HTN should be started immediately. Initially, it may be necessary to use parenteral drugs (labetalol, sodium nitroprusside) combined with oral drugs (ACE inhibitors/angiotensin II receptor antagonists, vasodilators such as calcium antagonists and other more powerful agents such as minoxidil plus beta-blockers and loop diuretics). Approximately 20% of cases require dialysis techniques.6,7 In our case, poor management of long-standing HTN, together with anabolic steroid use and intense anaerobic exercise, precipitated the development of malignant HTN. This disease requires immediate therapeutic action to prevent many complications leading to death in 25% of cases in 5 years, despite hypotensive treatment.

Please cite this article as: Merino García E, Borrego Utiel FJ, Martínez Arcos MÁ, Borrego Hinojosa J, Pérez del Barrio MP. Consecuencias renales del uso de esteroides anabolizantes y práctica de culturismo. Nefrología. 2018;38:101–103.