Content

To the Editor:

The incidence of bladder urothelial carcinoma in renal transplant patients on immunosuppressive therapy ranges from 0.08% to 0.37%, although it frequently occurs in advanced stages compared with the general population.1

Patients with high grade transitional cell carcinoma and/or carcinoma in situ may be able to benefit from intravesical instillations with bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG). The BCG is a live attenuated mycobacterium bovis that maintains immunostimulatory action, but with decreased infective activity.2

The management of bladder cancer in immunocompromised patients has been briefly described in case reports and retrospective series. We report the management of a renal transplant patient with carcinoma in situ, with immunosuppressive therapy at our institution.

Our patient is a 71-year-old male with chronic kidney disease due to IgA glomerulonephritis, who started haemodialysis in January 2004. In December of the same year, he received a deceased-donor kidney transplant and began receiving immunosuppressive therapy with mycophenolate mofetil and tacrolimus.

Five years later, he presented with haematuria with clots, and no other associated symptoms. Urine cytology was inconclusive and cystoscopy revealed a mass lesion of 1cm in the fundus of the bladder. Transurethral resection of the bladder was performed in August 2009. Anatomopathology: high-grade papillary transitional cell carcinoma (pTa G2). Carcinoma in situ. Intravesical mitomycin C (MMC) (6 weeks) was indicated. In December 2009, multiple bladder biopsy was performed randomly after MMC. Anatomopathology: bladder: carcinoma in situ (CIS) in the fundus of the bladder.

The case was presented to the Urology-Nephrology-Oncology Committee of our hospital and three weeks after surgery, the patient received 6 weekly intravesical BCG instillations. Anti-tuberculosis prophylaxis was added with 150mg/24h isoniazid and 300mg/24h rifampicin (starting the day before instillation, and ending the day after instillation). The tacrolimus dose was increased from 4 to 8mg/day. He completed BCG on 25 March 2010, without complications.

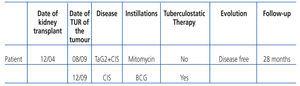

Tacrolimus plasma levels were maintained between 5 and 12ng/ml. Renal function remained stable with plasma creatinine levels of 1.2mg/dl. The patient experienced no adverse effects and was free of disease after 28 months of follow-up (Table 1).

DISCUSSION

The risk of bladder cancer increases about 2-3 times in the transplant population.3 Compared with the general population, transplant patients with a neoplasm de novo after transplantation are mostly diagnosed in advanced stages and have a lower survival rate.1 The use of immunosuppressive agents prevents graft rejection, but also means that transplant patients are predisposed to an increased risk of malignancy.4

Superficial transitional cell carcinoma (TCC) of the bladder with associated CIS or primary CIS may progress to invasive disease in 40% to 80% of the patients. A decrease in the recurrence and progression was obtained with the use of intravesical BCG that avoids, in many cases, the need for radical surgery.5

Intravesical BCG stimulates the type 1 T helper lymphocytes (Th1) of the urothelial cells in the mass production of proinflammatory cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-1, IL-2, IL-6, IL-8, interferon gamma and tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha. TNF-alpha has direct cytotoxic action on tumour cells.6

The main problem regarding BCG use is the associated morbidity. Lamm et al.7 state that 95% of patients tolerate BCG sufficiently, while less than 5% have serious complications. Theoretically, this morbidity would be expected to be greater in patients who receive immunosuppressive therapy after the transplant. Buzzeo et al.8 do not recommend the use of intravesical BCG in immunosuppressed patients.

Prophylaxis with isoniazid is administered with the aim of minimising toxicity induced by BCG, although, according to some authors, the frequency of cystitis, fever and feeling unwell do not differ between patients who receive intravesical BCG with or without isoniazid.9 This suggests that some complications occur due to inflammatory response and not due to the direct effects of bacteria per se.

Palou et al.10 reported safety in the administration of intravesical BCG with the use of prophylaxis with isoniazid and rifampicin in renal transplant patients with high grade superficial CCT of the bladder. Wang et al.11 also report safety, but without the use of tuberculosis prophylaxis in similar patients.

Medication with tuberculostatic drugs may cause adverse effects and increase the metabolism of some calcineurin inhibitors. Rifampicin induces cytochrome P450 3A4 and increases tacrolimus metabolism, with a dose adjustment being required to maintain the levels of immunosuppressants stable and avoid graft rejection.10

In literature we found 9 cases of kidney transplant patients with high-grade superficial CCT of the bladder and/or CIS, who received intravesical BCG, presenting a recurrence rate higher than the rate of the general population (44.4% compared with 26%). Rejection of the graft related to BCG use was not observed, probably because of the small number of cases recorded. One case of BCG treatment failure was reported.10-13

From an immunological point of view, there is a conflicting situation: immunosuppression is necessary to avoid graft rejection and immunological action is necessary to produce a cytotoxic effect on tumour cells.10 Systemic immunosuppression in transplant patients does probably not result in complete local immunosuppression; therefore, the inflammatory response with endovesical BCG could be effective. In deciding whether to use BCG in transplant patients, we should take into account the benefit of tumour control against the potential risk of graft loss or ineffective treatment.13

CONCLUSIONS

— Treatment with intravesical BCG in our patient with high grade superficial transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder was effective and did not experience adverse effects.

— It is possible that intravesical BCG in immunosuppressed patients with carcinoma in situ is a good treatment option.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest related to the contents of this article.

Table 1. Characteristics of the patient, treatment and follow-up