Acute tubulointerstitial nephritis (ATIN) leads to acute kidney damage; it has a low incidence in the paediatric population1,2 and is present in up to 15% of renal biopsies performed in adults for acute kidney damage.3 Currently, the most common cause of ATIN is drugs. Other causes include infection, immunological disease (such as systemic lupus erythematosus or Sjögren's syndrome), and sometimes the cause is unknown.4 Several groups of drugs have been identified as ethiological agents: antibiotics and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), which are extensively used in routine clinical practice, are among the most frequently implicated in ATIN.5

We present 3 cases of paediatric patients with non-oliguric acute kidney damage, seen in our department between 2008 and 2010, with a working diagnosis of NSAID-induced (ibuprofen) ATIN.

None of the children had a past history of kidney disease or other past medical history of relevance, and all had had blood tests in the previous months with normal creatinine levels and the estimated glomerular filtration rate according to the original Schwartz formula6 were normal. On physical examination, there were no signs of dehydration, blood pressures were normal for the patients’ age, sex, and height, and there was no oedema. There were no features of obstructive uropathy or evidence of glomerulopathy (C3 and C4 complement study, immunoglobulins, and ANA were normal). The 3 patients had received ibuprofen before developing kidney damage. The patients’ clinical characteristics and laboratory results are presented in Table 1.

Clinical details and investigations.

| Case number | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), gender | 4, male | 12, female | 12, female |

| Weight (kg) | 17 | 38 | 37 |

| Reason for taking NSAIDs | Urethroplasty | Headache | Appendicectomy |

| Duration of NSAID (days), dose | 5 5mg/kg/8h | 3 10mg/kg/8h | 4 10mg/kg/8h |

| Symptoms | Vomiting, abdominal pain, weakness | Macroscopic haematuria and fever | Nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite |

| Baseline serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.32 | 0.50 | 0.51 |

| Baseline urea (mg/dL) | 21 | 23 | 20 |

| Maximum creatinine (mg/dL) | 2.7 | 3 | 1.5 |

| Maximum urea (mg/dL) | 140 | 182 | 90 |

| Urinalysis | Some isolated red cells and white cells. No eosinophils | 100+ red cells/field and granular casts. No eosinophils | 1–2 leucocytes and 5–10 red cells/field. No eosinophils |

| Proteinuria with P:Cr ratio of 1.3mg/mg and tubular component. Osmo 262mOsm/kg | Proteinuria with P:Cr ratio 1.9mg/mg and tubular component. Osmo 453mOsm/kg | P:Cr ratio 0.3mg/mg. Osmo 303mOsm/kg | |

| Renal ultrasound | Kidneys mildly enlarged. Cortical hyperechogenicity and increased corticomedullary differentiation | Diffuse parenchymal hyperechogenicity of both kidneys with loss of corticomedullary differentiation | Diffuse cortical hyperechogenicity |

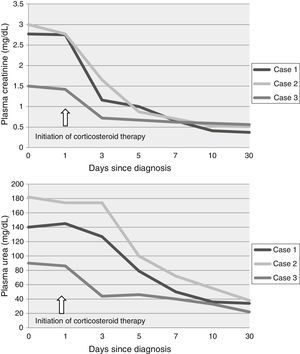

On admission, ibuprofen treatment was stopped in patients 1 and 3. Patient 2, who was referred from another hospital, had stopped the medication 2 days before admission to our department. Once a diagnosis of ATIN was suspected, treatment was started with intravenous methylprednisolone boluses (15mg/kg/day for 3 consecutive days, accounting for 250–500mg iv/day of methylprednisolone) followed by oral prednisolone (starting dose 1mg/kg/day) at a reducing dose, which was then stopped at 8 weeks. None of the patients had adverse effects attributable to steroids. Urea and creatinine returned to normal levels during the first week in all 3 cases (Fig. 1). Urinary biochemistry and sediment returned to normal within 6 months.

Drug-induced ATIN is the result of a cell-mediated hypersensitivity reaction to a drug. It occurs independently of the route of administration (intravenous, intramuscular, oral, or rectal)4 and the duration of treatment.7 Patients who have had drug-induced ATIN should avoid further exposure to the drug, as recurrence is possible.

The clinical manifestations are variable, and the severity of symptoms varies from asymptomatic urinary abnormalities to acute kidney damage (oliguric or non-oliguric), which may require extra-renal replacement therapy. The classic manifestations (fever, rash, and arthralgia) are present in only 10% of cases5; the most common manifestations are non-specific symptoms such as abdominal pain, vomiting, anorexia, weakness, or fever.

Urinalysis may show proteinuria (generally in the non-nephrotic range and predominantly tubular), haematuria, leukocytes, granular hyaline casts, and eosinophils (which are less common in the NSAID-induced ATIN). There may also be other clinical manifestations of tubular injury abnormalities depending on the segment affected (such as glycosuria, bicarbonaturia, tubular acidosis, inability to concentrate urine). A normal sediment does not exclude ATIN.

Ultrasound of the urinary system may show enlarged kidneys and increased echogenicity in the cortex.8 The gold standard for diagnosis is renal biopsy, which shows inflammatory cell infiltration of the renal interstitium (T lymphocytes, monocytes, macrophages plasma cells, eosinophils) along with local oedema and, occasionally, fibrosis. There may be tubulitis, and the vessels and glomeruli are usually normal.9 The first step in treatment is to stop the drug responsible and provide adequate supportive treatment for the degree of established kidney damage. Use of corticosteroids as part of the treatment has been debated for years; however, recent publications support their use because they have been demonstrated to improve the prognosis of renal function recovery. Therefore, starting treatment early is the main prognostic marker.10,11

Renal biopsy is the investigation of choice to confirm the diagnosis. However, none of our patients underwent biopsy, because they progressed well clinically and biochemically once the responsible agent was stopped (immediately after the diagnosis was suspected) and corticosteroid treatment was started. The corticosteroid protocol used, by González et al, is described above.10 The 3 patients showed a rapid response to treatment, and the outcome has been excellent. However, renal biopsy should be considered in cases that are slow to resolve or in case of diagnostic uncertainty.

It is important to explore the past drug history in patients with acute renal failure without previous renal disease or signs of dehydration, and in whom ultrasound of the urinary tract has ruled out obstructive causes. The first step in the treatment of ATIN is to stop the causative drug and provide adequate supportive therapy. Early administration of corticosteroids once a diagnosis is suspected is associated with early resolution of renal failure.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Martínez-López AB, Álvarez Blanco O, Luque de Pablos A, Morales San-José MD, Rodríguez Sanchez de la Blanca A. Nefritis intersticial aguda por ibuprofeno en población pediátrica. Nefrologia. 2016;36:69–71.